Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

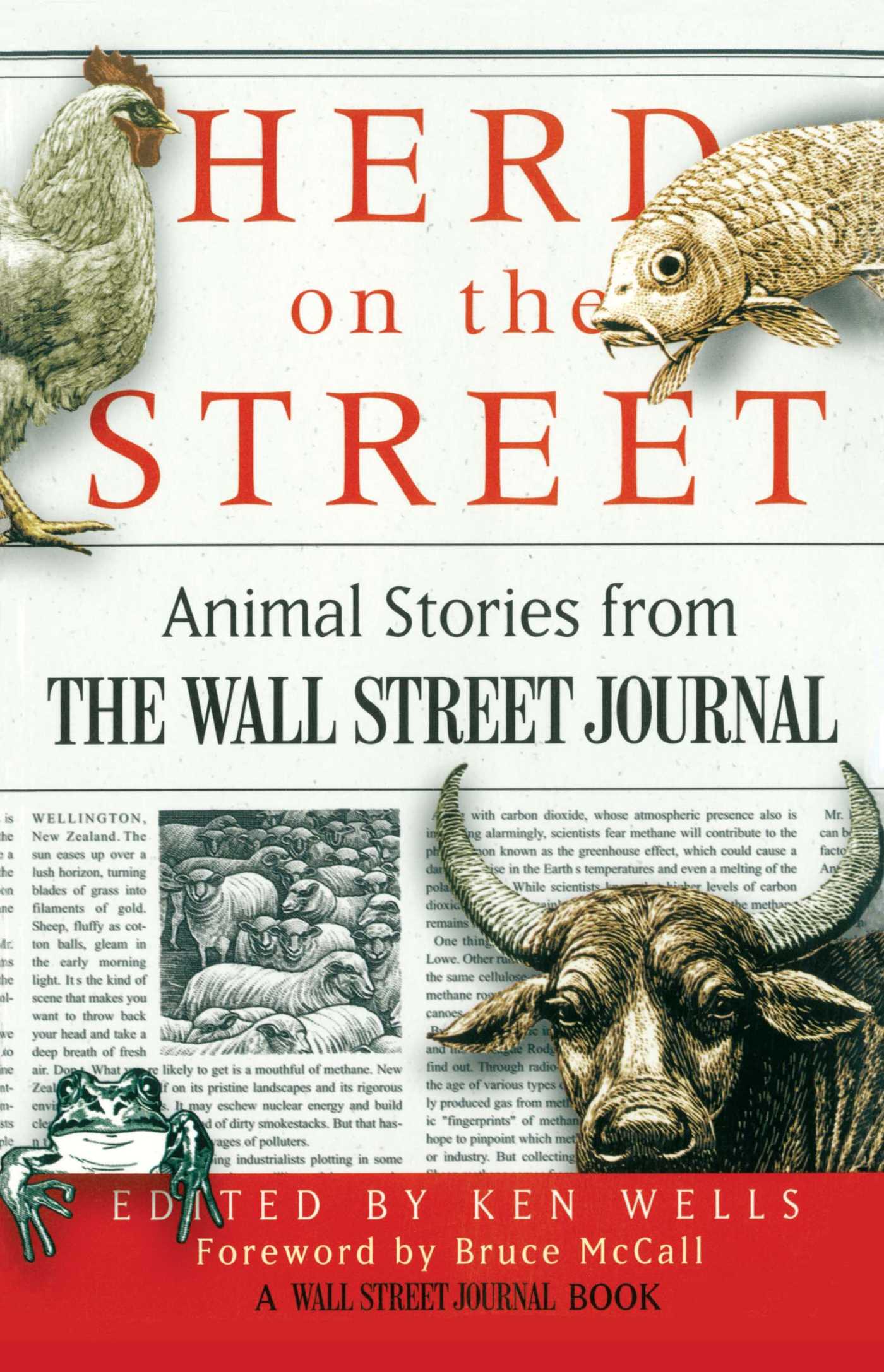

Herd on the Street

Animal Stories from The Wall Street Journal

Edited by Ken Wells / Foreword by Bruce McCall

Table of Contents

About The Book

For more than sixty years, The Wall Street Journal has prided itself not just on its serious journalism, but also on the whimsical and arcane stories that amuse and delight its readers. In that regard, animal stories have proven to be the most beloved of all. Now, veteran Journal reporter and Page One editor Ken Wells gathers the finest, funniest, and most fascinating of these animal tales in one exceptional book.

Here are lighthearted, witty stories of breakthroughs in goldfish surgery, the untiring efforts of British animal lovers who guide lovesick toads across dangerous motorways, and the quest to tame doggy anxieties by prescribing the human pacifier Prozac. Other pieces reflect on mankind's impact on the animal kingdom: a close-up look at the nascent fish-rights movement, the retirement of U.S. Air Force chimpanzees that once soared through space, and ongoing scientific efforts to defeat that most hardy enemy -- the cockroach.

Each of these fifty-odd stories -- from the outlandish to the poignant -- exemplifies the superb feature writing that makes The Wall Street Journal one of America's best-written newspapers. This charming and utterly captivating collection will be a joy not only to animal lovers, but to all those who appreciate artful storytelling by writers who are obviously having a wonderful time spinning the tales.

Here are lighthearted, witty stories of breakthroughs in goldfish surgery, the untiring efforts of British animal lovers who guide lovesick toads across dangerous motorways, and the quest to tame doggy anxieties by prescribing the human pacifier Prozac. Other pieces reflect on mankind's impact on the animal kingdom: a close-up look at the nascent fish-rights movement, the retirement of U.S. Air Force chimpanzees that once soared through space, and ongoing scientific efforts to defeat that most hardy enemy -- the cockroach.

Each of these fifty-odd stories -- from the outlandish to the poignant -- exemplifies the superb feature writing that makes The Wall Street Journal one of America's best-written newspapers. This charming and utterly captivating collection will be a joy not only to animal lovers, but to all those who appreciate artful storytelling by writers who are obviously having a wonderful time spinning the tales.

Excerpt

Chapter One: Pet Theories

1. Listening to Prozac: "Bow-Wow! I Love the Mailman!"

Prozac has greatly improved life for Emily Elliot. She had tried massage therapy, hormone treatments, everything; but she couldn't relieve the anxiety, the fear, the painful shyness.

Or the chronic barking. So, after three years Ms. Elliot recently put Sparky, her dog, on Prozac.

Sparky (not her real name) suffered from "profound anxiety" of strangers as well as "inter-dog aggression," says Ms. Elliot, a veterinary student at the University of Pennsylvania. The pooch "has a problem thinking through solutions to what is bothering her," she adds. So, in March, along with other therapies, doctors at the animal-behavior clinic where Ms. Elliot works prescribed Prozac.

Sparky, a show dog, quickly lost that hang-dog attitude. "It's been a big relief," says Ms. Elliot, who asked that Sparky's real name not be used because her Prozac use might influence dog judges.

Among American humans, of course, Prozac has become fashionable as a treatment for depression and obsessive/compulsive disorders. "It's the designer drug of the '90s," says Bonnie Beaver, chief of medicine at Texas A&M University's department of small-animal medicine. "People think, 'Gee, if I can have Prozac, why can't my dog?' "

The field is still new, but the growing potential for using Prozac and other human psychiatric drugs to treat destructive or antisocial animal disorders will be discussed at next month's meeting of the 52,000-member American Veterinary Medical Association. Prozac proponents say the drug, particularly for dogs, may represent the last chance to keep a maladjusted canine off of death row. Unruly behavior, which leads owners to abandon pets to shelters, is "the leading cause of canine and feline deaths" in the U.S., says Karen Overall, a University of Pennsylvania veterinarian.

"These vets are dedicated to finding ways to help pets stay with their owners," says an AVMA spokeswoman. "It's important to use all the avenues they can."

The University of Pennsylvania animal-behavior clinic has put depressed puppies on Prozac, feather-picking parakeets on antidepressants and floor-wetting cats on Valium (Prozac, for reasons not completely understood, has proved toxic and ineffective for cats, some veterinarians say). The clinic has also treated emotionally troubled ferrets, skunks and rabbits.

Some dogs on Prozac will be weaned off the medication, while others may be listening to Prozac for the rest of their lives, says Dr. Overall, who heads the clinic. "It's a great drug for some animals," she adds -- though she stresses that owners and pets should never take each other's medication.

The number of animals, including some birds, on Prozac is currently small, but anecdotal evidence as to its effectiveness is encouraging. In a letter to be published in the upcoming issue of DVM Newsmagazine, a veterinary journal, Steven Melman of Potomac, Md., describes a five-year-old dog suffering from "tail-chasing mutilation disorder." Conventional treatment failed and one vet suggested amputating the tail.

After five days on Prozac, though, the pooch was a "much more mellow, less restless patient," he writes. After five weeks on the drug, the dog's disorder was cured. Dr. Melman writes: "I had literally saved my patient's tail."

Using human drugs to treat certain animal conditions is "not at all controversial in mainstream medicine," says Dr. Melman. But Prozac has long been dogged by controversy. Thus, when Dr. Melman published a paper in the April edition of DVM describing Prozac use for dogs' skin problems caused by obsessive/compulsive urges, the fur began to fly. "I mentioned Prozac and people went nuts," he says.

The Church of Scientology, for example, responded with warnings that pets on Prozac could "go psycho." Since Prozac's launch six years ago, the Scientologists, who oppose the use of mind-altering drugs, have called it a "killer drug" linked to murder and suicide -- a charge roundly derided by the medical community.

If owners put pets on Prozac, "You may be forced to defang your dachshund or put Tabby in a straitjacket," warns a recent press release from the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, a group founded by the Church of Scientology. Yet, when reached for comment, the commission conceded it hadn't received any reports of injuries from Prozac-deranged pets.

Other groups are concerned as well. "There's a lot of room for fear and worries," says Bob Hillman, vice president of the Animal Protection Institute, a Sacramento, Calif., animal-rights organization. "Giving a Rottweiler or a Doberman Prozac could be dangerous for the neighbors" should the drug have an unintended effect.

The Food and Drug Administration and Eli Lilly & Co., Prozac's maker, have denied any link between Prozac and acts of violence or suicide. But "our clinical data support use of Prozac in treating only humans," says a spokeswoman for Eli Lilly. "We're not actively pursuing the study of Prozac for veterinary use."

Some animal advocates argue that, instead of turning to wonder drugs, people need to look for "gentle, noninvasive ways" of getting along with their pets, says Ken White, vice president for companion animals at the Humane Society of the U.S. in Washington. Ellen Corrigan, director of education for In Defense of Animals, another animal-rights group, suggests "a more holistic approach" that might include alternative treatments like acupressure and herbal remedies.

Indeed, doctors to humans often counsel patients to first try conventional therapy or behavior modification before they turn to Prozac. Pro-Prozac vets agree. With the appropriate diagnosis and dosage, drugs like Prozac can help pets, says Texas A&M's Dr. Beaver, but owners and doctors must find the real root of a pet's distress. "If you don't remove the stress, you don't fix the problem," she says.

Pennsylvania's Dr. Overall, who has plumbed the minds of pooches, notes: "If you pet them while they're moping, it just reinforces sad behavior." Instead, she recommends trying to get them to "take an interest in something they enjoy: Play with a ball, go for a car ride, sit on the sofa and watch TV. When they look happy, relaxed or outgoing, then give them a treat."

But determining a pet's neurosis takes time, and even Sigmund Freud wouldn't have gotten far with Fido on his couch. "We can't go up and say, 'Tell me about your traumatic puppyhood,' " says Dr. Overall. Still, she points out that depressed dogs exhibit many of the same signs that down-in-the-dumps people do: They don't eat, they don't sleep and they don't make eye contact. Many problems occur when the animal reaches social maturity, notes Dr. Overall. "The teen years are when we see a lot of social disorders in humans; gang involvements, schizophrenia. It's the same thing with cats and dogs."

Dr. Overall knows there are some people opposed to pet drug use of any sort. But she has put one of her three dogs on human antianxiety medication (though not Prozac) and is high on the idea. "I go home to normal dogs," she says.

-- Carrie Dolan, June 1994

2. Surgery on an Odd Scale

RALEIGH, N.C. -- Three veterinarians stood over a $4.95 goldfish named Hot Lips, prepping her for surgery. The senior vet, Craig Harms, slipped a syringe into the nine-inch-long fish's swollen belly. He drew out clear fluid -- a bad sign.

Dr. Harms retreated to the hallway, pulled out his cellphone and called the owners in New York's Catskill Mountains. It was Wednesday morning, August 14.

"Hot Lips is doing OK," he said, before delivering the bad news about the liquid. "It puts the possibility of liver disease or kidney disease back in the picture....We'll keep you posted as we move along."

Dr. Harms and his colleagues are among about 20 vets in the nation who perform surgery on pet fish. Not one of them makes it his sole practice. But the need for such services is growing. Americans are building more backyard fishponds, stocking up on pets that they swear have personalities of their own.

Large "pond-kept fish" rank as the fastest-growing fish-pets in the nation, while the broader category of fish ownership grows faster than dogs, cats, lizards or any other pet type, according to the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in Greenwich, Conn., and pet fish tend to grow bigger when they have more room to swim. Koi, the goldfish's fancy and often-expensive cousin, are particularly popular. They can live well past 30. So when these much-loved pets grow lumps or quit swimming, some owners give surgery a shot.

More are reaching out to Dr. Harms and his colleagues at North Carolina State University's College of Veterinary Medicine. One reason: Surgeons there have developed an advanced way to keep their patients alive on the operating table -- a portable device that pumps fluids, including anesthesia, into their mouths and out their gills.

The North Carolina surgeons will take cases that other vets consider hopeless. In March, they fused two crushed vertebrae along the spine of a 21-inch, $900 koi named Ladyfish. The three-hour procedure followed X-rays and a CAT scan. Ladyfish's owner, a North Carolina Roto-Rooter manager named David Smothers, recently brought in a smaller koi named Wendy for similar work. "To see this little girl swimming again, it's just incredible," Mr. Smothers says.

That expertise caught the attention of Deb and Greg Ireland, who live in Liberty, N.Y., about 90 miles northwest of New York City. The couple, in their mid-50s, bought Hot Lips three years ago when she was a three-inch baby. They picked her out of a pet-store tank because of the fish's striking snow-white body, reddish-orange back and small spot of color above her mouth.

The Irelands acclimatized Hot Lips to their pond, in a backyard oasis of gentle waterfalls, a barbecue grill and lounge chairs. Hot Lips grew into a svelte beauty, making friends with the couple's 25 other fish, among them Pinto, a large koi, and Alice, a naturally round oranda, a type of goldfish.

Last fall, the Irelands noticed some lumps on Hot Lips. "Maybe she's got some oranda genes in her," Mr. Ireland told his wife, hoping to ease her concerns. By spring, Hot Lips's stomach had swollen like a baseball. Mrs. Ireland gave her regular injections of antibiotics. That cleared up the sores but didn't reduce the swelling.

Mrs. Ireland began looking for a surgeon. By early August, she was telling surgeons at North Carolina State about a pink, bumpy growth protruding from Hot Lips's vent.

"How soon can you get her here?" veterinarian Greg Lewbart asked.

Three days later, the Irelands took Hot Lips to an aquatics shop in Warwick, N.Y., where she was specially packaged for overnight shipping. "Hang in there, Champ," Mr. Ireland said.

That night, Mrs. Ireland couldn't sleep and spent her time tracking Hot Lips's travel itinerary on the UPS Web site. By 10:00 a.m. the next day, Hot Lips had arrived safely in North Carolina. The operation was to take place the following morning.

The Irelands had reason to feel good about their surgeon. A native of Iowa, Dr. Harms earned his bachelor's degree in biology at Harvard, where he became taken with the idea of working with aquatic animals. He then went to vet school at Iowa State University. He has since had advanced training in microsurgery.

During the past eight years, Dr. Harms, now 41, has operated on about 125 fish, for pet owners and while teaching seminars for other vets. All but one fish survived. The pet owners generally pay between $350 and $1,000. Dr. Harms's research-journal articles have chronicled, among other cases, the removal of a hematoma the size of a pencil eraser from a three-inch gourami.

Operating on Hot Lips, Dr. Harms wedged the Irelands' goldfish into a V-shaped bed of foam rubber. The sedated fish was still, save for the motion of her gills as water and chemicals flowed through. A water pump provided the only constant sound in the room.

Dr. Harms, wearing aqua surgical scrubs and a light-blue mask, cut and retracted enough of Hot Lips's sides to reveal the first of two growths. With his fingertips, he gingerly probed beneath the yellow, slimy mass. "Looks like we got a big ol', fluid-filled, nasty ovary," Dr. Harms told his team.

The growth had been pushing into Hot Lips's central organ cavity, wending its way around her tiny colon. At Dr. Harms's request, one of the other vets inserted a catheter into Hot Lips's vent, hoping that it would support the colon as he cut near it.

No good. By the time Dr. Harms's instruments reached the colon, it had torn. He would have to repair it with surgical thread the thickness of a human hair.

At 11:04, Hot Lips stopped gilling.

Pam Govett, a vet assisting in the surgery, switched the anesthesiology flow device to pure, dechlorinated water. This supplied Hot Lips with oxygen in the same way a ventilator keeps human patients alive in a hospital. Next, the fish's heart became the big concern. Jenny Kishimori, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer now in veterinary school, put a tiny audio probe just below Hot Lips's throat. They couldn't hear a pulse, just water sloshing through the gills.

The team adjusted the probe. Finally, the sound of a steady, though slow, beat filled the room. "Thump-thump...thump-thump..." A low-normal 28 beats per minute.

Dr. Harms eventually removed two growths, which together accounted for about 40% of Hot Lips's weight, which had been 13 oz. But it was then clear exactly how sick she'd been. Damaged kidneys, scant body fat and pale gills suggested anemia.

Dr. Harms turned back to the frayed colon. He pinched its underside with forceps, rotating it enough to sew together a lateral tear. An assistant retracted the catheter slightly as saline solution ran back into Hot Lips's colon to test the fix. It held.

In New York, Hot Lips's owners waited by the phone. Nervous, Mrs. Ireland finally called the vet school, but could reach only an intake room. "Hot Lips hasn't made it back yet," she was told.

Forty minutes later, her phone rang. "It's not looking real good," Dr. Harms told her. He explained all his team had done. "The biggest concern for me right now is: She's been on pure water for over two hours and she hasn't started gilling," he said.

"Keep trying," Mrs. Ireland said.

Back in the operating room, Hot Lips's pulse had faded to 14 beats per minute. Dr. Harms injected her with adrenaline, which spiked her heartbeat to 32, but he didn't really expect that to last.

"Come on, Hot Lips," the soldier-turned-vet-student Ms. Kishimori pleaded, "wake up!"

Dr. Govett smoothed out Hot Lips's tail. "Such a beautiful fish," she said.

Nearly five hours after the procedure began, Hot Lips's pulse faded to nothing. Dr. Govett extended her thumb and forefinger into Hot Lips's chest, applying several minutes of CPR to try to start her heart.

"I think not," Dr. Harms said finally, walking out of the room to call New York.

-- Dan Morse, September 2002

3. A Horse Is a Horse,

Unless of Course...

LEXINGTON, Va. -- The world will little note nor long remember what was said here, but many will never forget the weirdness of what they did here this week. Six score and 14 years after his last ride in battle, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's war-horse was finally laid to rest in a walnut casket with prayer, pomp and a parting carrot.

At least part of him was.

"I wish they'd bury the whole horse," says Martha Boltz, gazing at Little Sorrel's hide, mounted on a lifelike frame on display at the Virginia Military Institute's museum here. Studying the horse's oft-repaired flank, she adds, "He looks like he's been reupholstered one too many times."

Mike Whitaker, another visitor, disagrees. "I've got deer mounts on my wall that look a whole lot worse," says the cookie distributor from North Carolina. "I say let the ol' boy keep riding as long as he's able."

How Little Sorrel came riding here at all is a long, strange story winding back to 1861, when Jackson, a brilliant Confederate commander, procured the reddish-brown horse from a captured Union train. Jackson, an awkward rider, liked the gelding's gentle gait -- "as easy as the rocking of a cradle," he wrote -- and often slept in the saddle. Mount suited master in another way; both were unimpressive physical specimens whose attributes weren't obvious. "Little Sorrel was as little like a Pegasus as he [Stonewall] was like an Apollo," wrote one Jackson aide. Others recalled "a dun cob of very sorry appearance" and an ugly "old rawbone sorrel."

But the small, dumpy mount proved tireless on the march and calm under fire, surviving a bullet wound and bolting just once, when Jackson was accidentally shot in the arm by his own troops as he rode in the dark during the battle of Chancellorsville in northern Virginia. His arm was amputated but the wound proved fatal to Jackson, who had earned his nickname for his "stone wall" defense of rebel lines at the first battle of Bull Run.

After the war, Little Sorrel toured county fairs and rebel reunions; souvenir seekers tugged so many hairs from his mane and tail that the horse required guards. In death, at the age of 36 -- just three years short of Stonewall -- the horse's fate again mimicked its master's. Jackson was buried in pieces, his amputated arm at Chancellorsville, the rest of him in Lexington, where he had taught at VMI before the war. His horse, meanwhile, was mounted on a plaster of Paris frame by a taxidermist who took the bones home to Pittsburgh as partial payment.

Both bones and hide eventually found their way to VMI, where the skeleton was used in biology class and the mounted hide displayed in the school museum. Then, when the science department relocated in 1989, the bones languished in moving boxes in the museum storeroom.

"It seemed weird and sad to me that Little Sorrel was never buried," says Juanita Allen, head of the Virginia division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Not long ago, she visited the horse's boxed remains. "I picked up his teeth and rubbed his nose bone. I was petting it and talking to him, telling him how sorry I was and how we'd take care of him."

Ms. Allen, an executive assistant at McKinsey & Co., a consulting firm, decided the Daughters should bury the horse with military-style honors. To her, this seemed the Christian thing to do, as well as a natural extension of the never-ending interest in the Civil War. "You can only talk so many times about what your great-grandfather did at this or that battle," she says. "But no one ever talks about the animals, who had no choice in the matter. They were just faithful beasts of burden who suffered terribly." An estimated 3.5 million horses and draft animals died in the war. Ms. Allen got VMI to agree to bury Little Sorrel's bones on the parade ground where the horse had once grazed, but this raised a ticklish question. What about the hide? Standing stiffly in a diorama-like display scattered with stones and leaves, Little Sorrel's hide has cracks on its face and lines on its flank where the leather has separated over the years.

"He's done with the Yankees -- humidity's his worst enemy now," says the museum's director, Keith Gibson, who calls in a taxidermist from the Smithsonian Institution every few years to glue the hide's tears and seal the cracks with beeswax. Despite its flaws, the horse remains the main draw at VMI's small museum, which attracts 50,000 visitors a year. The gift shop sells Little Sorrel postcards, refrigerator magnets and cuddle toys. Visitors even leave apples at the mounted hide's feet.

"This place is a reliquary, it's a piece-of-the-true-cross kind of thing to be close to Sorrel's remains," says University of Pennsylvania Civil War historian Drew Gilpin Faust, visiting Lexington to witness the horse's burial. Even so, Ms. Faust finds the mount's fate and enduring appeal a tad strange. "You have to wonder," she says, "if Southerners wanted to stuff Stonewall Jackson but stuffed his horse instead."

Nor is Little Sorrel's hide the only shrine in Lexington, a Shenandoah Valley town of about 7,500. Robert E. Lee, the South's most prominent general, also worked here. For Civil War pilgrims, the town's other holy sites include the two generals' graves, Stonewall's house, an exact life-size statue of Lee and the nearby grave of his war-horse, Traveller. Visitors often leave carrots and coins on Traveller's grave, and flock to the stable -- now a garage -- where he was kept.

"If it wasn't for our dead generals and their dead horses this town would be, well, dead," says Doug Harwood, publisher of the Rockbridge Advocate, a Lexington newspaper. He is often bemused by the town's idol-worship. "You turn a corner in the VMI museum and come face to face with the mighty Stonewall's mighty war-horse -- and it looks like it couldn't pull Donald Duck in a wagon." But even Mr. Harwood turned out this week for the burial of Little Sorrel's cremated bones. Originally, VMI hoped to keep the interment quiet, even planning a night burial for fear of turning the event into a circus. But as word leaked out, and interest grew, it became clear that Little Sorrel would not ride quietly into the night. In the end, it took a minister, bagpipe player, fife-and-drum band, color guard -- even a Stonewall impersonator astride a horse meant to resemble Little Sorrel -- to lay the horse's remains to rest.

Nikki Moor, who bought the horse for her Stonewall-playing husband, concedes that the handsome Arabian isn't a perfect match of Jackson's mount, but it is the closest she could find. "Most people don't advertise that they have a short, fat ugly horse for sale," she says.

The interment, held beneath a statue of Stonewall, drew about 500 people, including women in period mourning garb. After prayers and speeches and the playing of "Dixie," pallbearers clad as rebel soldiers lowered the coffin as Confederate riflemen fired musket volleys. Then the crowd filed past the grave and scooped in clods of dirt gathered from 14 battlefields where Little Sorrel served. Some mourners also tossed in carrots, oats and horseshoes.

"Once again, Little Sorrel is beneath Stonewall Jackson," intoned James Robertson, a Jackson biographer. "May you continue to have good grazing in the boundless pastures of heaven."

After the burial, the crowd proceeded to the nearby museum to pay their respects to Little Sorrel's hide, still on its frame. Even the cynical publisher, Mr. Harwood, was struck by the dignity of the event. "You didn't see anyone trying to cash in with T-shirts or tacky mugs," he said. "There wasn't even a politician here."

But Mr. Harwood did wonder if the remains might have been put to better use. "We could have traded these bones for Stoney's arm up in Chancellorsville and brought the limb back here," he said. "Now, we've got no more relics to swap."

-- Tony Horwitz, July 1997

4. Much Chow, No Hounds

CARNATION, Wash. -- Edward Kane is up to his whiskers in cats. Cat posters adorn his office walls. Cat food crowds his shelves. Cat magazines clutter his desk. Cat eyes stare from a pin on his starched white lab coat.

The 37-year-old Mr. Kane talks cats, cats, cats. Cat business litters his mind: cats to mate, cats to groom, sick cats, cats that won't eat.

Especially cats that won't eat. Cats that won't eat are a real problem.

Mr. Kane sneezes, then excuses himself. "Allergic to cats," he says sheepishly.

The bespectacled, affable Mr. Kane runs Carnation Co.'s "cattery." Here in the pastoral Snoqualmie Valley about 20 miles east of Seattle, more than 500 cats reside in a sort of feline commune -- and eat for, not into, the corporate profits.

They are the cat version of gourmet food tasters, nibbling a pungent pâté of this, sampling a crunchy nugget of that. Their food preferences are computerized and scientifically translated by Mr. Kane and others for Carnation's pet-foods division, based in Los Angeles. There, product managers and marketers gamble that what tickles these feline palates will please cats all across the nation.

The cats, which taste-tested about 250,000 cans of moist cat food and 70,000 pounds of dry varieties last year, seem to be doing a good job. Carnation, the nation's No. 2 pet-food maker (behind Ralston Purina Co.), had pet-food sales of $486 million in fiscal 1983. About 60% of the total came from sales of the company's Friskies, Fancy Feast and other cat-food brands.

"The cats," says Ronald Stapley, Carnation's farm-research director, who formerly ran the cattery, "aren't just necessary: They're critical."

Dwight Stuart, Jr., a great-grandson of Carnation's founder, E. A. Stuart, says, "It's kind of neat knowing that our success is largely in the hands of those little beasties." The 38-year-old Mr. Stuart is, so to speak, the Top Cat of Carnation's pet-foods division. At least once a year, he visits the cattery to look in on his furry helpers.

The cattery, as it happens, is just down the hill from the barns where Carnation's famous Contented Cows still lead an idyllic bovine life. It's also one of only two large-scale cat taste-testing and nutrition-research facilities in America. Ralston Purina runs the other, near St. Louis.

Carnation began its cattery with only 44 cats in 1953, about the time commercial cat food was beginning to jump onto supermarket shelves in quantity. The cattery grew slowly to about 300 cats by 1970. Until then, Carnation and other pet-food companies concentrated on the lucrative multibillion-dollar dog-food market, which had its beginnings in the 1930s. (Carnation has operated a taste-testing kennel for dogs since 1932.)

But in the 1970s, pet cats, to the surprise of pet-food producers, climbed sharply in popularity. Mr. Stuart attributes the boom partly to the "mystique of the cat" -- cats not long ago even made the cover of Time magazine. But the main factor, he thinks, was a shift toward urban living, which favors pets that fit into compact living space and need less attention. The cat, small, cheap to feed, independent and fastidious, answers the job description, he adds.

Today, cats have begun to challenge dogs as America's favorite pets. Though dogs still hold the lead -- there are perhaps 55 million to 60 million pet dogs in America -- cats have almost doubled in just the past 15 years to 43 million currently.

And cat-food sales, a modest $500 million nationwide in 1973, grew to about $1.6 billion last year and are expected to hit $2.7 billion by 1992. Americans also spent another $1 billion or so last year on feline vaccinations, vitamins and veterinary services.

"The cat-food side of the industry is where the growth is," Mr. Stuart says.

To capitalize on that growth, Carnation decided to get even cozier with cats. So, since 1970, it has almost doubled the cattery's capacity to 550 cats and has stepped up its research to answer lingering questions about cat nutrition and food preferences.

The nutritional requirements are fairly well known, Mr. Kane says. The mysterious things are the finicky feline appetite and the cat's penchant to seem bored one day with the very food that it downed voraciously the day before. This "food fatigue," as Mr. Stapley calls it, helps explain why pet-food companies make so many flavors and textures of cat food -- and why they are as nervous as cats at a dog show.

"We know we've basically got one chance with the consumer," Mr. Stuart says. "If the cat walks up to the bowl, sniffs at it and walks away, the owner is probably off to the supermarket for someone else's brand."

So, Mr. Kane spends long hours trying to demystify cat idiosyncrasies about food. He oversees perhaps 200 to 250 tests a month, mostly dealing with "food acceptance." The tests are straightforward: White-coated clinicians scoop out measured portions of cat food into stainless-steel bowls. The food is weighed, the weight punched into a computer.

The cats, each with his own computer number, eat. The bowls are taken away, and the food is weighed again to determine the amount consumed. That information is also punched into the computer, which calculates how much the cat liked the vittles. The tests not only involve new products, which can take up to two years to develop, but often cat food on the market for years.

"Quality control," Mr. Kane explains. The cat palate is so sensitive to even minute changes in flavor that Carnation uses taste testing results to make sure that its longtime products don't drift from the tastes that made them popular.

Sometimes, too, the company has to change an existing recipe slightly because it can't get a customary ingredient from a supplier. In those cases, the cats -- under considerable deadline pressure -- help make multimillion-dollar business decisions.

"If we have to change an ingredient, we don't want to make a large batch of food using the new ingredient without knowing how the cats will react," Mr. Stuart says, so, a factory often air-freights a test batch to Mr. Kane, who feeds it to his cats overnight, quickly runs the results on his computer and phones headquarters the next day with the results. Whole factories sometimes are held up until the cat data are digested. Sometimes, so much is at stake that the cat stats go all the way up to Carnation's chairman, H. E. Olson, before the company decides what to do.

"The results are only a tool. We might say, 'Well, it looks pretty good to our cats.' But they [pet-foods division officials] make the final decision," Mr. Kane adds.

The cats also help Carnation check up on the competition. They often eat rival brands, served in identical bowls alongside Carnation products. The company concedes that now and then, its cats devour competing food with disconcerting relish.

"If that happens, I don't get depressed, at least not right away. But I get very inquisitive and want to find out what's going on," Mr. Stuart says. Mr. Stapley adds cryptically, "We probably know as much about our competitors' products as they do."

Though the testing is done with scientific efficiency in a hospital-clean environment, all sense of clinical decorum is lost at feeding time.

"Hold on, it's coming," says a cattery worker as she pushes a large cart full of pungent cat food into a room where about 25 cats live in airy, stainless-steel "apartments." She is greeted with a cacophony of meows. Cats in the next room join in, and suddenly the whole place is vibrating with hungry-cat noises.

Down the hall, a few cats are singing different tunes: wails, purrs, shrieks.

"Oh, that," Mr. Kane says. "Mating season, you know." Mr. Kane, in fact, is the principal matchmaker, importing one or two male cats a year to add vigor to the cattery's bloodlines. But almost all the cats here are descendants from the original 44. Most are just plain tabby cats; Carnation discovered long ago that what common cats eat, fancy cats eat, too.

Common or not, the cats here seem to be treated royally. They all have names -- such as Faustus, Pong, Sly, Secret Agent and, yes, Garfield -- and Mr. Kane knows practically all of them. Each cat is groomed and weighed weekly, gets regular physical checkups and is fussed over by a full-time veterinarian on call 24 hours a day. There aren't any fat cats here; tubby tabbies are put on a diet. Every day, juveniles and young adults romp for several hours in a kind of cat gym. And mating cats are paired off in little private suites where cat love can flower without disruption.

Indeed, the cattery's only drawback is that the cats spend most of their time in cages -- a necessity, considering the logistics involved in feeding, caring for and keeping track of research on more than 500 of them. There are some exceptions: Some taste-testing is carried out by cats living in large, open communal rooms, though the exact object of those tests, like much of what goes on here, is kept secret.

What isn't secret, however, is Mr. Kane's fondness for cats -- despite his allergy, he has seven of his own at home -- and his unabashed conviction that his cats are the best-fed felines in America. Mr. Kane, in fact, speaks from personal experience.

"I eat the cat food routinely," he says. "I like it." So does Mr. Stuart, who says key employees of the pet-foods division get together regularly to talk, and nibble, cat food.

"We get very close to the product," Mr. Stuart says.

-- Ken Wells, April 1984

5. Polly Wants a Scholarship to Harvard

EVANSTON, Ill. -- It is always awkward for a reporter when a source stops answering his questions, moves closer and gently chews his ear. But allowances must be made for eccentric geniuses.

The biting intellect here is an African Grey parrot named Alex, a research animal at Northwestern University. For 13 years he has fraternized only with people and now regards them as members of his flock -- sometimes even preening the scruffier ones about the ears. But identifying with humans isn't what makes him special.

Nor is his ability to whistle some Mozart and say things like "Tickle me." Parrots, after all, are uncanny mimics. But Alex isn't just a copycat. Asked the color of a bluish pen held before him, he cocks his head, ponders and expounds: "Baaloo!"

The Prof. Henry Higgins behind this former squawker is animal-intelligence researcher Irene Pepperberg. For 13 years she and her assistants have tirelessly acted out a kind of Sesame Street for Alex. Like Big Bird and friends, they perform simple word skits, day after day, while he watches in a small room stocked with toys, snacks and perches. They have slowly drawn him into the act.

Now he can name 80 of his favorite things, such as wool, walnut and shower. (Studiously copying Ms. Pepperberg's Boston accent, he says "I want showah" to get spritzed.) He knows something about abstract ideas, including soft, hard, same and different. He can tell how many objects there are in groups of up to six. When he says, "Wanna cracker," he means it: Handed a nut instead, he drops it and exclaims in his peevish old man's voice, "I WANT CRACKER." So much for the idea that our feathered friends are all just bird brains.

Some other animals, such as chimpanzees, have learned nonverbal communication. But Alex is the first animal to actually speak with a semblance of understanding. Ms. Pepperberg believes his conversational gambits prove that he can handle some simple abstractions as well as chimps and porpoises can.

When shown a group of varied objects Alex has learned to answer certain questions such as, "How many corners does the piece of red paper have?" with about 80% accuracy. That is, if he is in the mood. When bored, he tells his teachers to "go away" and hurls test objects to the floor. "Emotionally, parrots never go beyond the level of a three-year-old" child, sighs Ms. Pepperberg, a young 41-year-old, patiently picking up toys Alex has strewn about his room in an orgy of play.

Skeptics argue that Alex isn't as smart as he seems. He has "learned to produce a repertoire of sounds to get rewards," says Columbia University animal cognition expert Herbert Terrace. "The only thing distinguishing him from pigeons [taught to peck buttons for food] is that his responses sound like English."

But regardless of whether Alex grasps meanings as we do, he shows an "incredible, totally unexpected" power to make mental connections, notes Ohio State University psychologist Sarah Boysen, who works with chimps. Before Alex, scientists generally dismissed talking birds as mindless mimics.

For her part, Ms. Pepperberg sidesteps the fray, merely noting that Alex shows "languagelike" behaviors. But she adds that parrots in the wild routinely perform mental feats -- such as learning to sing complex duets with their mates -- that prove they have a lot on the ball. Biologists sometimes call them "flying primates" -- they have even shown evidence of using tools. Once when Alex couldn't lift a cup covering a tasty nut, he turned to the nearest human assistant and demanded crowbar style, "Go pick up cup."

Parrots tend to go loco and pluck out their feathers when caged alone, says Ms. Pepperberg, so they generally don't make good pets. Yet the talking-bird trade is booming, endangering many parrot species. Alex, whom Ms. Pepperberg bought for $600 in a Chicago pet store in 1977, may himself have been nabbed in the jungle. And he probably isn't an avian Einstein -- he is just highly schooled. "It's possible I got a dingbat," his coach says.

If so, he proves how much inspired teaching can do for the dingy. Ms. Pepperberg, who took up bird research while getting her chemistry doctorate at Harvard University, has helped pioneer a new training strategy for animals that stresses humanlike learning by social interaction. "There's been a lot of resistance to my work," she says, "because I don't use standard techniques." But not from Alex.

Standing on a chair, he is all eyes and ears as she and an assistant hand back and forth a date nearby -- they're trying to add it to his lexicon. "I like date," says Ms. Pepperberg. "Give me date. Yum." Suddenly Alex ventures, "Wanna grain." "No," says Ms. Pepperberg, "date. Do you want date?" Alex preens, seemingly mulling it over. Then he says, "I want grape." That's good enough for now. She hands it to him and he takes a bite.

Another of her tricks resembles the way parents help tug their toddlers into verbal being -- by acting as if babbling is meaningful. When Alex says something new, Ms. Pepperberg tries to "map" it to something he is likely to remember. After he learned "rock" and "corn," and spontaneously said, "rock corn," she got dried corn and began using that term for it. Similarly, "peg wood" was mapped to clothespin and "carrot nut" to the candy Boston Baked Beans. Alex no longer gets candy, though, for it makes him hyperactively "bounce off the walls, saying 'I want this, I want that,' " says Ms. Pepperberg.

Alex often seems to play with words like kids learning to talk. Overnight tape recordings revealed he privately babbles to himself, perhaps practicing new words. Once he saw himself in a mirror and asked, "What color?" -- that's how "gray" was mapped. When a student blocked him from climbing on her chair, he uttered the only curse he's heard: "You turkey!"

These untrained signs of wit may be just "babble luck," says Ms. Pepperberg. Still, Alex sometimes seems to be groping for linguistic connections. Soon after first seeing apples, he called one a "banerry" -- a word he hadn't heard. "No," Ms. Pepperberg gently reminded him, "apple." Alex persisted: "Banerry," he said, "ban-err-eeee" -- speaking as his teachers do with new words. He still uses banerry, says Ms. Pepperberg, which after all makes sense: An apple tastes a little like a banana and looks like a big cherry, fruits he already knew.

Today, the gray eminence is again doing it his way. When Ms. Pepperberg holds up two keys and repeatedly asks, "How many?" he plays dumb. Finally, she calls a "time out," leaving the room. Moments later, Alex looks at me, eyes the keys, and spits out, "Two."

-- David Stipp, May 1990

6. Two-Stepping with Four Legs

HERSHEY, Pa. -- As Julie Norman two-stepped across the dance floor, her partner, resplendent in a matching red bandanna, stayed flush by her side, sidestepping as she sashayed, two-stepping backward with her to "The Devil Went Down to Georgia." As the final guitar chords twanged, Ms. Norman knelt down to the Astroturf floor, tossing her cowboy hat into the air. Her partner, Sprint, a seven-year-old border collie, caught the hat, then leaped into Ms. Norman's arms. As the audience cheered, a three-judge panel sat poker-faced on the far side of the ring, judging the pair on technical merit and artistic impression.

Welcome to the Northeast Offlead Regional for the World Canine Freestyle Organization: Think Fred Astaire meets Best in Show. No longer is it enough for Fido to simply march around a ring. In this new sport, handlers perform (many aficionados eschew the word "dance") with their pups, to musical accompaniment. Worldwide, there are now dozens of freestyle competitions and exhibitions each year in which dogs and their owners disco, line dance and fox trot to tunes ranging from Rodgers and Hammerstein to the Rolling Stones.

At the moment, there are 2,500 or so freestyle competitors around the globe, and their ranks have been growing quickly, quadrupling in the last few years. In fact, there are already two competing freestyle groups, which differ on the extent of costuming and human involvement they allow. The World Freestyle organization (www.worldcaninefreestyle.org), founded by Patie Ventre, a onetime competitive ballroom dancer who sports rhinestone dog-bone earrings, is considered to be the more prohuman and procostume. Ms. Ventre has high hopes for the contests, aiming to get them included as a demonstration sport in the Olympics.

For now, though, freestyle has some distance to go in terms of garnering serious respect. Ms. Ventre has had a tough time winning significant sponsors -- the major dog-food companies are devoting their resources to show dogs. ("The [show] dogs are generally better looking," says a spokesman for Heinz North America.) Meanwhile, the 50 or so competitors at the two-day Northeast Regional were relegated to the second tier of the parking garage at the convention center here in Hershey.

The venue may have been somewhat informal, but the competitions are anything but. Canine freestyle has two categories of events, heelwork-to-music (think ice dancing) and musical freestyle (more like pairs skating). Scores are then divvied up into a series of categories including content (three points), precise execution (two points), flow (two points), stepping in time to the music (one point) as well as use of ring space (75% is required for big dogs, 50% for those 20 pounds or under). Costuming counts: A maximum of 1 1¿2 points is awarded depending on how well costumes are coordinated with the routines. Points are deducted for excessive barking and canine inattention -- scratching and floor-sniffing are definite no-nos, as is piddling in the ring, a misstep that got one Labrador disqualified at the North Central Regional in Michigan this May.

Maintaining canine concentration can be a challenge. As Peg Shambaugh and her border collie Belle did their routine to Lawrence Welk's "Beer Barrel Polka," Belle paused briefly to tend to a possible flea. Ms. Shambaugh tried to camouflage the slip by quickly mimicking the move. "Cute," said judge Mary Jo Sminkey, "but it won't win her any extra points." (Ms. Sminkey is a former competitor who got out of the ring because her own six-year-old Shelty, Taz, who nestled under the table as she watched the competition, "likes other sports better.")

Judges are trained to account for dogs' breeds -- terriers are cut extra slack, while the bar is set a little higher for Shelties and border collies since they're considered easier to work with. "A Briard is difficult to train let alone dance with," explains the announcer. Meanwhile, in the ring, Mrs. Beasley, a buff Briard -- a large French herding dog known for its lush coat and obdurate personality, defies her breed by doing figure-eights through the legs of her owner, grooving to Paul Simon's "You Can Call Me Al."

Linda Blanchard's German Wirehaired Pointer, Robbie, is somewhat more reluctant, balking as Ms. Blanchard tries to coax him to prance with her to "I'm Looking Over a Four-Leafed Clover." Ms. Blanchard concedes she is as much a novice in some of the finer stylistic moves as Robbie. "I've done classical music and dog training -- but I don't have much dance background," she says. "I just started classes this summer." What master and dog may lack in function, though, they make up for in form: Ms. Blanchard wears a custom-made green sequined number straight out of Busby Berkley, while Robbie wears a matching collar. The sequins paid off; though Ms. Blanchard and Robbie came in near the bottom of their division, they took the show's award for best costume.

As for rest of the performances, Ms. Norman and Sprint walked off with one of the top trophies; Mrs. Beasley the Briard and her owner took second, and a Schipperke who trotted to Elmer Bernstein's "Magnificent Seven" took the bronze. "I usually win," says Ms. Norman, "but this is the first time I've had any competition."

-- Lisa Gubernick , September 2001

7. Big Bird Is an Emmy Shoe-In

BEAUFORT, S.C. -- In tidal marshes just a short distance from where scenes were filmed for Forrest Gump, R. J. Sorensen is making his own audience-pleaser. He lacks a big-movie budget. But luckily, his actors will work for chicken feed.

After pouring a bag of seed into a plastic feeder, he retreats behind his camera, waiting for his cast of grackles and cowbirds to arrive. "Take One!" he says, as the camera begins to roll.

Mr. Sorensen, 48 years old, is out to make the ultimate video for the bored house cat. His first movie, Kitty Show, took four years and half a million dollars to make. It featured a cast of bugs and fiddler crabs. It sold 100,000 copies, at $19.80 each, mainly through Mr. Sorensen's Web site. It got a "Two Paws Up" rave from Catnip, a publication of the Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine.

Mr. Sorensen believes his new film will move its audience even more. "If I was a cat," he says as he looks through his viewfinder, "I'd tear the hell out of the TV."

People who live with cats know that some love watching television. Baseball and tennis are big with sports fans, who will perch atop the set and swat at the screen. And just about any old movie will satisfy a cat who's in the mood to sit and watch. It provides company if not companionship.

Between the cat owner's guilt about leaving Tabby home alone and Tabby's obvious affinity for television, there is opportunity for auteurs like Mr. Sorensen.

Ruth First, who lives in a New York studio apartment, says she no longer worries about leaving her cats alone at night. Before going out, she says she puts a little cat chair in front of the TV along with some catnip and treats. Then she pops a cat video into the videocassette recorder. Hannah, her domestic shorthair, "is mesmerized by it," says Ms. First, a spokeswoman for the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Cats, finicky in all things, have their niche favorites, be it Kitty Safari, Feathers for Felines or The Adventures of Larry the Lizard.

The genre was born in 1989 with Video Catnip: Entertainment for Cats, a 25-minute tape of chipmunks, birds and squirrels. Total sales: about 350,000 copies, says Steve Malarkey, the film's producer. Mr. Malarkey says he hadn't expected a perennial bestseller. "We figured we'd get a couple of years out of it and a few yucks," he says.

Video Catnip's success brought copycats and cat fighting. Steve Cantin (Cat Adventure Video) calls himself the Steven Spielberg of cat videos. "I know how to take creative energy and turn a profit," he says.

Before he made cat films, Mr. Cantin made "TV art," videos aimed at creating moods for humans. One was The Ultimate Fireplace Video, described on the box as "the next best thing to having your own fireplace....No chopping wood...no cinders and soot to clean." Another was The Ultimate Aquarium Video, a fish tank that doesn't have to be cleaned.

Mr. Cantin economized by reusing Aquarium Video footage in his Cat Adventure Video. But this time a Tufts Veterinary reviewer wasn't amused. She panned the fish-swimming scenes, which, oddly, have a voice-over of birds chirping. She wrote that the scenes "bored all cats silly." She gave the video "Two Paws Down."

Mr. Cantin isn't fazed. Cat Adventure Video was picked up by Publishers Choice, a mass marketer owned by National Syndications, Inc., and advertised in Parade. Mr. Cantin is now working on a Cat Sitter DVD that can be played all day long. His goal for the year: $1 million in cat-video sales. "I'm out to sell volume," Mr. Cantin says.

As to his rivals, Mr. Cantin is less generous. He pans Video Catnip as gimmickry larded with "funky, goopy music." As for Mr. Sorensen's Kitty Show and its four-year gestation, he says, "I don't think they spent that much time on the atom bomb."

Says Mr. Sorensen: "It's a cutthroat business....My goal is not volume, it's happy cats."

A onetime paramedic, Mr. Sorensen cut his cinematic teeth producing medical videos. But he says he would get home from two-day trips to find three depressed cats, "so I decided to invent a product that would keep their attention." Mr. Sorensen tested some of the other cat videos on his pets. His cat Milo, he says, hid under the bed after seeing Video Catnip -- terrified by a close-up of a squirrel that made the creature look bigger than life. He says he took the tape out in the yard and "shot it to death" with his shotgun.

Out to make something more congenial, he lavished attention on Kitty Show. He filmed the tail twitches, raised fur and eye movements of several test cats as they watched a variety of critters pass across high-resolution monitors. He shaved cats' chests and hooked them up to electrocardiographs. He learned that cats are particularly excited by purple, green and yellow, but see reds and browns as grays. Rapid movements, he says, would increase a cat's heart rate by 40 beats. Cats, he decided, are crazy about insects and bugs.

Filming Kitty Show was rough. At night, Mr. Sorensen says, he illuminated his yard with floodlights. Two helpers ran around swooping up bugs with butterfly nets while Mr. Sorensen filmed in "the bug room," his studio. The biggest problem, Mr. Sorensen says, was keeping the insects moving. Also, his moths at first tended to immolate themselves on the lights.

To film the bugs, Mr. Sorensen says he invented a special lens filter that enhanced cat appeal by adding "low wave" purple colors to the white images. The result: two hours of fluttering moths, crawling beetles and creeping spiders set against backgrounds that alternate every 20 minutes.

This sort of action probably wouldn't interest anybody who isn't on drugs, Mr. Sorensen says. But then, "I'm not interested in what people think. I'm interested in what cats think."

To find out exactly what cats think of Kitty Show, Mr. Sorensen scheduled a screening at an animal shelter in nearby Hilton Head. As the shelter's director looked on, Mr. Sorensen turned on a TV set and slid a tape into the VCR. Not much happened at first, but soon enough, as the Fellini of feline film beamed, a pair of cats hissed and growled, as they competed for space in front of the set.

-- James Bandler, July 2001

8. Barking Mad for Joyce

GRESHAM, Ore. -- When you read to a dog and he seems to be sleeping through the best parts, he is actually "listening with eyes closed." That's the word from Natalie Shilling, youth librarian at the Gresham branch of the Multnomah County Library.

Ms. Shilling introduced a "Read to the Dogs" program here last year after learning about the Salt Lake City Public Library's literary, listening dogs. They are certified therapy dogs guaranteed to act interested (or at least not run away) while a child reads aloud, even if they've already heard George and Diggety a zillion times.

Children tend to choose pack-pleasing, canine-themed books for their 30-minute sessions with the dogs and their unobtrusive handlers. When I visited the Gresham library, I found 11-year-old Shawn Helgeson about to launch into a spirited reading of Watchdog and the Coyotes to a yellow Lab named Patrick.

Shawn noted that the book had already scored a paws-up from Howard, another library dog. "It's hilarious," Shawn said. Sure enough, as he read about the watchdog that only watched, Patrick appeared to be laughing. Minutes later, however, the dog closed his mouth, along with his eyes, and commenced listening with eyes closed.

Patrick's owner, Rachel Timmon, said that before Shawn came along, two little boys had been showing Patrick picture books. One book was about taking a bath. "Patrick hates baths," Ms. Timmon revealed. But Patrick had tactfully concealed his distaste for the topic, possibly even laughing in the face of it.

Ms. Shilling, the librarian, has five dogs of her own, all pint-sized Cavalier King Charles spaniels, and every one a therapy dog certified through Portland's Dove Lewis Emergency Animal Hospital. The hospital has trained an entire menagerie of pets (including dogs, cats, birds and llamas) that visits patients in hospitals and nursing homes.

When Ms. Shilling read in School Library Journal about the Salt Lake City library's partnership with Intermountain Therapy Animals, she realized that the key to a similar, local program lay snoozing in her lap.

Results from the Salt Lake City library's "Dog Day Afternoons" and related school programs showed that reading aloud to a nonjudgmental, unconditionally loving canine audience was having a positive effect on erstwhile problem readers. There was a marked increase in technical skill and personal confidence. Furthermore, petting while reading provided a natural tranquilizer for high-strung children.

In 1999, critical-care nurse and animal lover Sandi Martin literally dreamed up the Utah program, springing up in bed at 2:00 A.M. and jotting down her thoughts. After refining her idea with Intermountain Therapy Animals, for which she is a board member, she called Dana Tumpowsky, the library's community relations manager, and asked her to try it. "I thought, 'This woman's crazy,'" confessed Ms. Tumpowsky.

Crazy like a fox, perhaps, or even a Portuguese water dog, like Olivia, Ms. Martin's own reading therapy dog, which before dying of cancer helped build READ (Reading Education Assistance Dogs) into a nationally known, copyrighted program. In this year alone, READ has fielded more than 400 inquiries from libraries and schools.

The READ program had its debut in November 1999, when six dogs and their handlers settled down on the library floor with six young readers. Ms. Martin and Olivia composed one dog team that day.

"You'd see kids with their finger in a book and a hand on a dog," recalled Ms. Martin. "It was just kind of magical."

By January 2000, children's librarians at all six branches had requested the literary dogs, which are washed with antidander shampoo before their visits. They are identified by their red bandannas and their handlers' red T-shirts.

"It's not like anybody can walk in with their dog," explained the library's Ms. Tumpowsky, who not once has had to say "Shhhhh!" to a READ dog.

Ms. Martin said the handlers take their jobs as seriously as the dogs do. The owner of an Akita is busy trying to teach her dog how to turn pages of the kids' books. The trick is placing a small morsel of kibble between pages.

"The kids think he's mesmerized by the story, but he's really waiting to turn the page so he can get the treat," she said.

When I visited Portland's Hollywood branch library, one of five local branches that has adopted the "Read to the Dogs" program, the dog on duty didn't appear to possess similar talents. In fact, Alyx, 10, an interesting mix of golden retriever, Labrador retriever, Newfoundland and border collie, was most adept at listening with eyes closed.

Her handler, Liz Johnston, was the one with all the tricks: a Polaroid camera, so the young reader's session with Alyx would be immortalized, and a reading certificate featuring Alyx's portrait.

I arrived just as Emma Crabtree, age seven, was gathering up her books and preparing to pose with her reading audience. Ms. Johnston set to work rousing the deeply listening dog, while Emma's mother, Linda Crabtree, kept her distance.

"I'm allergic to dogs," she explained. "If they lick me, I break out in hives."

The next scheduled reader was a no-show, so Ms. Johnston invited me to read to Alyx. Just as the children usually do, I scurried through the stacks, desperately looking for anything with dog in the title. But by force of habit, I had gone to the adult fiction section. No dog tales leaped out at me. So I took a copy of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake from the shelf. Alyx, as usual, was nonjudgmental, while Ms. Johnson clearly would have preferred hearing yet another "Henry and Mudge" story. But that didn't stop her from snapping my photo and awarding me a certificate.

Back home, I tried reading aloud to my dog, Daphne. But, lacking the appropriate training, Daphne ran away, tossing me a look that seemed to say, "Reading? That's for the birds!"

-- Susan G. Hauser, August 2001

9. Little Beauties

SOWERBY BRIDGE, England -- Jack Wormald, the founder of the Calder Valley Mouse Club, says his "fancy" for these furry little animals began more than 50 years ago when he attended the local agriculture show.

The owner of the best-mouse-in-show that day was a man who would become a legend in the world of exhibition mice, the late W. Mackintosh Kerr from Glasgow. "I was just so excited and thrilled by Mr. Kerr's mouse -- it was an all-black with a lovely sheen -- that I couldn't get over it," says Mr. Wormald.

Mr. Wormald wrote Mr. Kerr, expressing his admiration for these show mice, and Mr. Kerr mailed him "a trio" -- a starter set of two does and a buck. The rest, as they say, is history. Mr. Wormald estimates he has bred 200,000 mice in the last half-century, twice winning the coveted Woodiwiss Bowl, named in honor of Sam Woodiwiss, who founded the National Mouse Club and became its first president in 1895. The solid-silver punch bowl goes to the best in show at the highlight event on the mouse-show calendar, held annually at Bradford. "There is," says Mr. Wormald, "no greater honor."

The 74-year-old Mr. Wormald was here in industrial west Yorkshire the other day for the Calder Valley show, which attracted about 50 exhibitors and 230 animals. It was a lively scene on the top floor of the St. John's Ambulance Corps rooms, with three judges, all dressed in long white coats (two of them with Mouse Club patches), inspecting the contestants, one by one.

The mice are packed in little green "Maxey cages," invented by the most famous mouse man of all, the late Walter Maxey, almost always referred to as the "father of the mouse fancy." Mr. Wormald is proud to say he owns the original Maxey cage, which was recently repaired by his friend and fellow mouse fancier, Frank Hawley.

"We took off layer after layer of paint," says Mr. Hawley. "When we got down to the original wood, we could dimly make out the letters EVILLE ORAN. Sure enough, he'd made the cage out of a box that had contained Seville oranges."

The judge reaches -- carefully -- into the cage and pulls the squirming mouse out by its tail. He examines its ears, checks its coat, measures the length of its tail. Sometimes he blows on the animal, to ruffle its fur, so he can look at its undercoat. He lets the mouse run up and down his arm, to see how lively it is.

"This is serious business," says Edward Longbottom, the longtime secretary of the Calder Valley club. "We are as careful in the way we breed mice as horse owners are in the way they breed Thoroughbreds."

Standards are rigid. "The mouse," according to the rules of the National Mouse Club, "must be long in body with long, clean head, not too fine or pointed at the nose. The eyes should be large, bold and prominent, the ears large and tulip shaped, free from creases....The tail must be free from kinks and should come well out of the back and be thick at the root, gradually tapering like a whiplash to a fine end, the length being about equal to that of the mouse's body."

Graham Davidson, one of the judges here, says the most famous mouse of all -- Mickey -- "would never get out of the cage at one of our shows." Mickey Mouse, he says, is "too fat, his ears are too round and his tail looks like somebody pasted it on."

Mouse judging usually begins with the "selfs" -- animals that come all in a single color. Recognized colors are black, blue, champagne, chocolate, cream, dove, fawn, red, silver and white. A perfect self would win 100 points -- 50 for color, 15 for general condition, 15 for overall shape and carriage, and five apiece for shape of ears, eyes, muzzle and tail.

There are other varieties with special markings and combinations of colors -- Himalayans, chinchillas, silver foxes, argente cremes, marten sables, silver agoutis, rump whites, seal point Siamese.

It costs about 10 cents to enter a mouse in any of the recognized Mouse Club shows, the same price exhibitors paid 50 years ago. And the cash prizes haven't changed, either -- 50 cents for first place, 30 cents for second and 15 cents for third.

"We do it out of love -- and for the social companionship involved," says Mr. Hawley, who won the Woodiwiss Bowl several years ago with his all-black Jetset Prince, still a legend among the mouse-fancy set. Jetset Prince, unlike most exhibition mice, which are killed when they pass their prime, was allowed to retire, living out a full three-year life, rich with honors.

Mr. Hawley estimates he travels 6,000 miles a year to compete in mouse shows. He is usually accompanied by three fellow mouse fanciers, who share the cost of the gasoline. "You've got to be out there almost every weekend between March and October if you expect to come up with grand champions," Mr. Hawley notes.

Most mouse fanciers are amateur geneticists, constantly attempting to come up with a mouse with new and unusual colors or markings. Your name, then, goes into the book (G. Atlee, for example, is credited with the Himalayan mouse, in 1897; Miss Mary Douglas discovered the champagne mouse in 1911). Mouse breeders understand that you begin to create cinnamons by crossing an agouti with a chocolate, yielding a litter of all agoutis. Breed these agoutis together and you come up with three cinnamons per litter of 16 babies. Each generation, the breeder culls out -- kills -- the babies that won't serve the purpose.

The mouse fanciers' bible, Tony Cooke's Exhibition and Pet Mice, spells out with charts and diagrams how it is accomplished.

It's a far cry from the ordinary wild mouse, Musmusculus, which has a shorter tail and smaller ears and which is normally a dull gray-brown in color. These exhibition mice, the experts say, carry a little Japanese strain in them, introduced by the legendary Mr. Maxey, who bought Oriental mice from sailors who brought them home as pets at the turn of the century.

Pink-eyed mice, in fact, can be traced back to Japanese mice called "Waltzers." They got that name, according to Mr. Davidson, the judge, "because they had a brain disorder that caused them to run around in circles." Waltzers were crossed with ordinary wild mice -- and the babies appeared with pink eyes. Better still, the babies didn't waltz.

The mouse fancy, with nine clubs active in London and the industrial Midlands, is largely an English phenomenon (there are no clubs in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland). The only other countries that show much mouse interest are Holland and Germany. Efforts to interest Americans haven't been too successful. "They tend to be namby-pamby; they don't take it seriously," says Frank Hawley. He thinks there may still be an active mouse group in Fontana, Calif.

Most of the mouse fanciers come from quite ordinary working-class and middle-class backgrounds (Mr. Maxey, the fancy's father, was a mailman). They are warm, cheerful people, hoping outsiders will try to understand their innocent fun.

par

"These shows are social events as much as anything else," says Mr. Longbottom, the secretary of the local club. His wife, May, has been coming to shows for 50 years, even though she doesn't care for mice at all. "I despise them," she says. But, all the same, she has been voted a life member of the National Mouse Club.

The mouse fanciers look down on the rat fancy.

The National Fancy Rat Society holds regular shows, too, though, nationally, it is much smaller than the mouse group. "I don't care for rats," says Jack Wormald, twice the winner of the Woodiwiss Bowl. "They are very coarse."

-- James M. Perry, March 1986

10. Fido Forever

Jackie Hibbard's voice softens when she recalls how her dog, a terrier-mutt named Itchy, was hit and killed by a car two years ago.

But even in death, Itchy is there every morning when the 40-year-old Gilliam, Mo., resident wakes up. Itchy lies on the bedroom floor, her head on her paws and her eyes wide open.

Ms. Hibbard had her freeze-dried.

More of the nation's estimated 73 million pet owners are having their departed companions freeze-dried, instead of buried or cremated. The bereaved say turning their furry friends into perma-pets helps them deal with their loss and maintain a connection to their former companions -- at a fraction of the cost of preserving them through traditional taxidermy.

Freeze-drying, generally used for preserving food or purifying chemicals, also retains some individual characteristics like facial expressions that don't survive standard taxidermy, proponents say. "It's comforting," says the 40-year-old Ms. Hibbard. "If you can see her all the time, you really have those wonderful memories."

Freeze-drying has also given the sleepy taxidermy industry a new lease on life, letting many studios expand beyond their traditional hunting-and-fishing clientele. Mike McCullough, owner of Mac's Taxidermy in Fort Loudon, Pa., started freeze-drying animals about five years ago. About all he needed to get started were two freeze-dryers, which cost him $22,000. In addition to dogs and cats, he says he also gets the odd request to do a family bird or lizard. Pet preservation now accounts for 5% of his shop's annual revenue of about $80,000.

"It's getting to be a really big deal," says Mr. McCullough. "The profit margin is phenomenal."

Freeze-drying pets is still rare. Elden Harrison, president of the Joppa, Md.-based Pet Lovers Association, estimates that less than 1% of the dogs that die each year end up freeze-dried. And it upsets many animal lovers. In a recent survey by MeowMail.com, a Massachusetts-based electronic community for cat lovers, the 2,600 subscribers who responded overwhelmingly rejected freeze-drying. "It's kind of disgusting and demented," says subscriber Heather Marshall, a 23-year-old in Phoenix. "The question is, would you freeze-dry your child or mother or sister or father? Probably not."

Some taxidermists also turn up their noses at transforming family pets into permanent fixtures. "I don't do it here. I don't want to skin a dog," says Cally Morris of Hazel Creek Inc. Taxidermy of Green Castle, Mo.

Still, the practice is gaining acceptance. "We endorse it," says Mr. Harrison of the Pet Lovers Association, which advises owners on "disposition options" for dead pets.

Gail Timberlake, who owns a catering business in Winchester, Va., doesn't care what others think. Her Chartreux cat, Father Ron, is in the freeze-dryer right now. He will return home in March to resume his spot on the white bedroom chair he once used for afternoon naps.

"I just loved that little guy," says Ms. Timberlake, who found the alternatives to freeze-drying distasteful when she had to put the cat to sleep at age 21. "Ashes? I don't think so. Buried in the ground with the worms? I don't think so," she says. "This way, I can always look at him and kiss him goodnight."

Alan Anger, president of Freezedry Specialties Inc., which sells freeze-drying equipment, says he began promoting pet freeze-drying to taxidermists about five years ago after working with museums to preserve animal specimens. "We saw that the process was the same for doing trophy animals and domestic animals," he says.

He now promotes the practice through what the company calls "Friends Forever," a marketing scheme under which taxidermists purchasing the equipment pay a licensing fee in return for training and referrals from the company.

Taxidermists who favor freeze-drying say it's far easier than traditional wildlife mounting. Preserving a deceased animal the traditional way involves skinning it, removing internal organs, cleaning away muscle and other tissue through cooking, rebuilding the bone structure and tanning the hide. Then the skeleton must be padded with foam and other materials, and the preserved skin refitted and sewn on. Mr. McCullough, the Fort Loudon taxidermist, charges as much as $2,000 for a traditional job on a small dog.

Freeze-drying avoids nearly all of that labor, preserving the animal with much less expense. Mr. McCullough, for example, charges between $550 and $600 for a poodle, depending on the size.

The virtue of the process, which was commercialized after World War II to preserve blood plasma, lies in its ability to evaporate water directly from ice to vapor without it ever turning into water.

Al Holmes, who runs a taxidermy studio and wildlife museum in Wetumpka, Ala., starts by manipulating the animal's body into an appropriately meaningful pose. He works from snapshots and consultations with the owners. Then he puts the animal in a regular freezer until solid. From there it goes into a special freeze-dryer. In Mr. Holmes's studio, this is an imposing steel cylinder with a four-inch-thick Plexiglas window. As refrigerators cool the interior to 12 degrees Fahrenheit, a powerful pump sucks out the air, creating a near-perfect vacuum. Little by little, the ice in the corpse escapes as water vapor, which is pulled out of the chamber.

Small animals take about two months to dry completely, while large dogs need as long as six months. "We go by feel," says Mr. Holmes. "We open the machine every other week. When all the water is gone, there's nothing to freeze and they actually feel warm. Then you know he's ready."

Once dried, the animal's bodies don't decay.

Early efforts to freeze-dry family pets produced specimens that later became infested with insects. Taxidermists say they've solved that problem by injecting the pets with solutions of formaldehyde and other preservatives before putting them in the freeze-dryer.

Family pets can also be difficult because so many are overweight. Sometimes, all the fat doesn't completely dry, leading to problems in the afterlife. "You start getting some oozing," says Anthony Eddy, owner of Anthony Eddy Wildlife Studios, Slater, Mo.

But this is nothing a little cotton batting and some household repair equipment can't solve. After surgically removing fat deposits, "I go in there with a caulking gun," he says.

The technical subtleties don't matter to Tauna Hadley of Kansas City, Kan. Her Weimaraner, Weimar Lee, died of cancer in 1999. Now she sits proudly atop a living room wardrobe. "It's like she's asleep," says Ms. Hadley. "She's still a pet. She's just not a live pet."

-- Jeffrey Krasner, January 2001

Copyright © 2003 by Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

1. Listening to Prozac: "Bow-Wow! I Love the Mailman!"

Prozac has greatly improved life for Emily Elliot. She had tried massage therapy, hormone treatments, everything; but she couldn't relieve the anxiety, the fear, the painful shyness.

Or the chronic barking. So, after three years Ms. Elliot recently put Sparky, her dog, on Prozac.

Sparky (not her real name) suffered from "profound anxiety" of strangers as well as "inter-dog aggression," says Ms. Elliot, a veterinary student at the University of Pennsylvania. The pooch "has a problem thinking through solutions to what is bothering her," she adds. So, in March, along with other therapies, doctors at the animal-behavior clinic where Ms. Elliot works prescribed Prozac.

Sparky, a show dog, quickly lost that hang-dog attitude. "It's been a big relief," says Ms. Elliot, who asked that Sparky's real name not be used because her Prozac use might influence dog judges.

Among American humans, of course, Prozac has become fashionable as a treatment for depression and obsessive/compulsive disorders. "It's the designer drug of the '90s," says Bonnie Beaver, chief of medicine at Texas A&M University's department of small-animal medicine. "People think, 'Gee, if I can have Prozac, why can't my dog?' "

The field is still new, but the growing potential for using Prozac and other human psychiatric drugs to treat destructive or antisocial animal disorders will be discussed at next month's meeting of the 52,000-member American Veterinary Medical Association. Prozac proponents say the drug, particularly for dogs, may represent the last chance to keep a maladjusted canine off of death row. Unruly behavior, which leads owners to abandon pets to shelters, is "the leading cause of canine and feline deaths" in the U.S., says Karen Overall, a University of Pennsylvania veterinarian.

"These vets are dedicated to finding ways to help pets stay with their owners," says an AVMA spokeswoman. "It's important to use all the avenues they can."

The University of Pennsylvania animal-behavior clinic has put depressed puppies on Prozac, feather-picking parakeets on antidepressants and floor-wetting cats on Valium (Prozac, for reasons not completely understood, has proved toxic and ineffective for cats, some veterinarians say). The clinic has also treated emotionally troubled ferrets, skunks and rabbits.

Some dogs on Prozac will be weaned off the medication, while others may be listening to Prozac for the rest of their lives, says Dr. Overall, who heads the clinic. "It's a great drug for some animals," she adds -- though she stresses that owners and pets should never take each other's medication.

The number of animals, including some birds, on Prozac is currently small, but anecdotal evidence as to its effectiveness is encouraging. In a letter to be published in the upcoming issue of DVM Newsmagazine, a veterinary journal, Steven Melman of Potomac, Md., describes a five-year-old dog suffering from "tail-chasing mutilation disorder." Conventional treatment failed and one vet suggested amputating the tail.

After five days on Prozac, though, the pooch was a "much more mellow, less restless patient," he writes. After five weeks on the drug, the dog's disorder was cured. Dr. Melman writes: "I had literally saved my patient's tail."

Using human drugs to treat certain animal conditions is "not at all controversial in mainstream medicine," says Dr. Melman. But Prozac has long been dogged by controversy. Thus, when Dr. Melman published a paper in the April edition of DVM describing Prozac use for dogs' skin problems caused by obsessive/compulsive urges, the fur began to fly. "I mentioned Prozac and people went nuts," he says.

The Church of Scientology, for example, responded with warnings that pets on Prozac could "go psycho." Since Prozac's launch six years ago, the Scientologists, who oppose the use of mind-altering drugs, have called it a "killer drug" linked to murder and suicide -- a charge roundly derided by the medical community.

If owners put pets on Prozac, "You may be forced to defang your dachshund or put Tabby in a straitjacket," warns a recent press release from the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, a group founded by the Church of Scientology. Yet, when reached for comment, the commission conceded it hadn't received any reports of injuries from Prozac-deranged pets.

Other groups are concerned as well. "There's a lot of room for fear and worries," says Bob Hillman, vice president of the Animal Protection Institute, a Sacramento, Calif., animal-rights organization. "Giving a Rottweiler or a Doberman Prozac could be dangerous for the neighbors" should the drug have an unintended effect.

The Food and Drug Administration and Eli Lilly & Co., Prozac's maker, have denied any link between Prozac and acts of violence or suicide. But "our clinical data support use of Prozac in treating only humans," says a spokeswoman for Eli Lilly. "We're not actively pursuing the study of Prozac for veterinary use."