Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

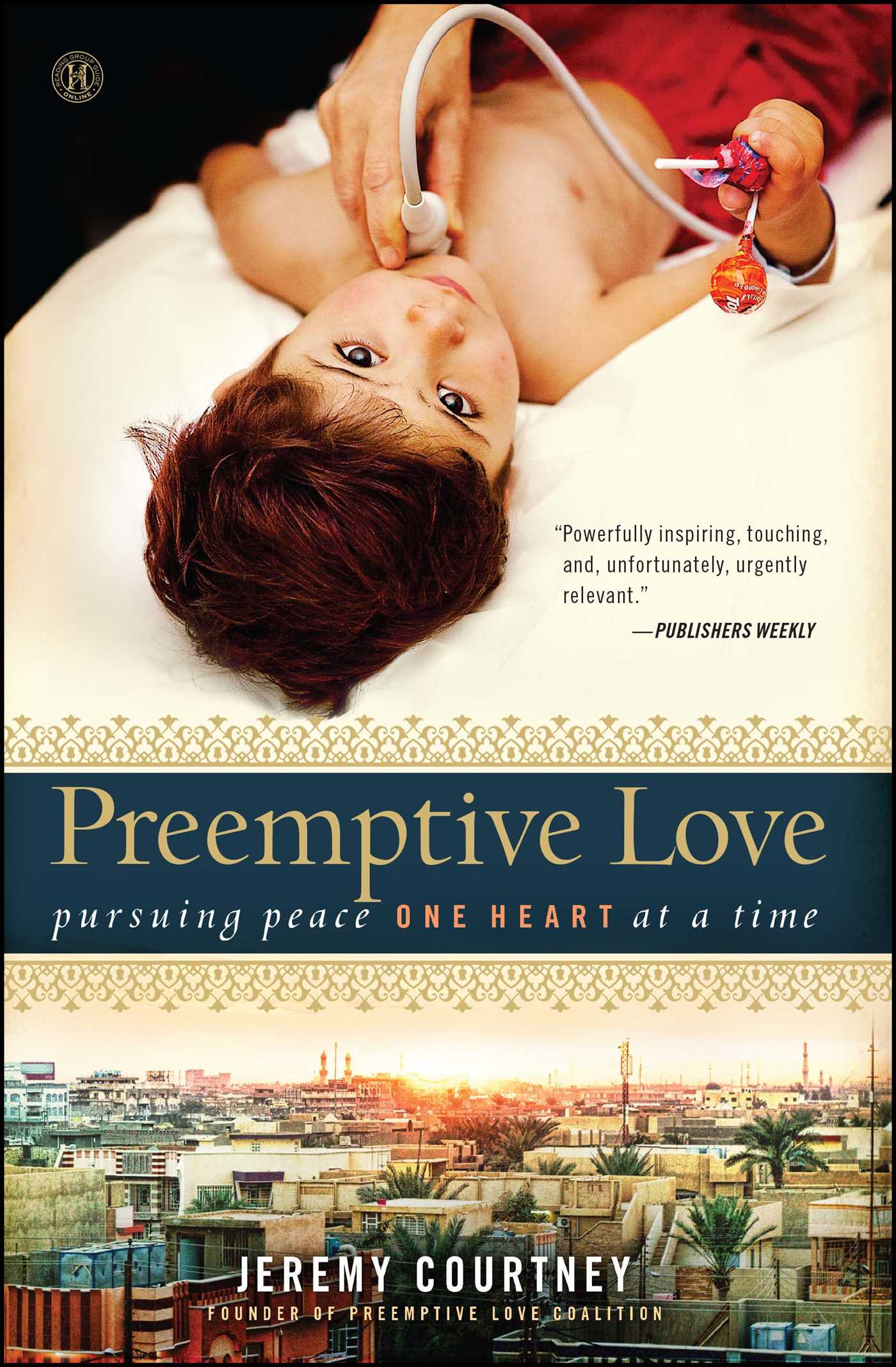

In the middle of the Iraq War, Jeremy and Jessica Courtney found themselves with their two children caught up in the turmoil, just hoping to make a difference. After an encounter with a father whose little girl was dying from a heart defect, they began to investigate options for helping and learned that untold thousands of children across Iraq were in similar need, waiting in line for heart surgery in a country without a qualified heart surgeon.

With the help of their closest friends, they dived in to save the lives of as many as they could, but sending children abroad proved to be expensive and cumbersome, and it failed to make an impact on the systemic needs of Iraqi hospitals—the place where these children really should be saved. Despite fatwas, death threats, bombings, imprisonments, and intense living conditions, Jeremy and his team persevered to overcome years of hostilities and distrust in an effort to eradicate the backlog of thousands upon thousands of Iraqi children waiting in line for much-needed heart surgery.

“This true story of people coming together to live the doctrine of 'love first, ask questions later' by building bridges and saving lives is powerfully inspiring, touching, and, unfortunately, urgently relevant” (Publishers Weekly). “Courtney’s moving story gives us some of the best news to come out of Iraq in ages” (Los Angeles Times).

Excerpt

How many times have I sat behind the ominous blast walls in this Iraqi hotel? Will I really be protected if a car bomb goes off outside? (I would get that answer soon enough.) The gaudy orange decor was offensive at first, but I eventually resigned myself to it. It can be so difficult to see things for what they are, even more so to see what they could be.

I never had a room there at the hotel. Unlike most of the journalists and aid workers who frequented the hotel, I wasn’t on assignment. With our families expressing deep concern over the targeted killing of Christians in Iraq, Kurdish-Arab tensions on the rise, and the Sunni-Shia civil war in full effect, my wife, Jessica, and I felt compelled to take our beautiful baby girl and move to Iraq.

We lived in a house down the street from the hotel, in a neighborhood called Peace.

In the winter, when the neighborhood only had about three hours of electricity per day, our home was frigid and dark. But it taught us an invaluable lesson: we don’t need power to live in Peace.

Sure, we longed for power. It would have made everything easier! We even bought a small gasoline generator to run the lights and our computers, but using it was like announcing, “We have money, and you don’t!” So after a few can’t-live-without-it moments, we decided not to use it again.

The spring was pleasant, but by the summer our house had become a brick oven. Jessica was pregnant with our son while trying to care for our daughter. Most days she navigated life in Iraq with little or no water and electricity. Without a working knowledge of local languages or a car to get around the city, she felt like a prisoner. It was becoming increasingly clear that we had not chosen an easy path, and our marriage was suffering.

One thing that simultaneously made my life better and her life worse was the hotel up the road with its Hollywood classics on the lobby big screen, air-conditioning, and table-side tea service. The hotel served as an office for my work with war widows, but also as a place of retreat from the difficulties of life outside. It gave respite. It was an oasis, far away from some of the difficulties of life in Iraq. If my clothes smelled of burned coffee and other men’s cigarettes when I walked in the front door, Jessica knew where I’d been. And I could pretty much guarantee I wasn’t getting that “Honey, I’m home” hug. If there is one thing Jessica cannot abide, it is the feeling that everyone is not getting their fair share. And she certainly was not getting hers.

It was Jessica’s beauty and her utter lack of pretension that first drew me to her in college. But it was her passion for fairness that kept me close. Sure, I found it easy to mock (“Life’s not fair!”) as I awkwardly groped for attention and security with a woman who was utterly out of my league. But there is something completely enchanting about a woman who believes that life should be fair, not for her own sake, but for the sake of everyone else. Still, talk is cheap. Few women are serious enough about fairness and justice to run toward the broken, forgotten people of the world. That’s Jess. She doesn’t have a vapid bone in her body. And it was ultimately her character and conviction that compelled us to move to Iraq.

But conviction and naivety are good friends. We nearly destroyed our marriage trying to help everyone else. Like a Scud missile through the roof, our marriage came crashing down around us during a terrifying yelling match in 120-degree heat where I thought my life was ending. But things were about to turn around.

I imagine it took days for him to get up the nerve to approach me. He probably had to talk himself into it, given the changing perspectives on Americans in Iraq and our inability to speak each other’s language. He may have even rehearsed his speech a few times.

I had been visiting his hotel café for months. We were familiar with one another, even friendly. But on this particular day, he had a favor to ask. In and of itself, this was not unique. I was constantly asked to give money, sponsor a green card, or teach English. Most of the Iraqis I knew were very accustomed to being rejected for these things. There was not often a lot of push-back or sense of entitlement for many of the favors we were asked to bestow. But this guy was different. I remember him being fairly solemn—as if it really mattered and he wanted to get it right.

As he nervously asked for permission to present his request, I remember thinking . . .

Nothing. I don’t remember thinking anything. This was just another conversation for me. I had not been building up to this for days. I did not have anything riding on this conversation. I certainly did not know that his request would change my life forever.

“Can you help my cousin?” he said. “His daughter was born with a huge hole in her heart, and no one in all of Iraq can save her life. Can you help?”

If you are like me, you hear heroic stories and you wonder, What would I do in that situation? I’m sure I would wear the white hat and save the day.

My answer to his earnest appeal came quite easily.

“I can’t help you. I don’t know anything about that.”

I did not need any rehearsal time. My list of justifications was waiting at the gate to be unleashed.

∙ I’m not a doctor.

∙ I’ve never done that before.

∙ I don’t know anything about sending children abroad for treatment.

∙ I don’t have that kind of money.

∙ My organization does not handle situations like that.

At this response, my friend (he was obviously more a friend to me than I was to him) could have attacked my character, quoted how much money I had spent on coffee and tea over the past months, lambasted me for my hypocrisy, or come at me just for being an American. Instead, he did the exact opposite. Rather than condemn me, he praised me. Like Jessica and her conviction that the world should be fair, he was totally disarming.

He appealed to my obvious desire to make things right in the world and said, “Mr. Jeremy, you are an American, right? Clearly you didn’t move your family to Iraq to say no to people. You want to help people. You are a good Christian. You did not move here to say no. You moved here to say yes. Please say yes to my cousin, Mr. Jeremy.”

There was so much fear in my initial rejection of his need. I was so unsure of myself and where I stood in the world. I was not a leader in my organization, and my marriage demonstrated how lame a leader I was in my own home as well. I was so vulnerable to any number of attacks that he could have launched. He could have won the argument by laying waste to me and my attempt to hold his family’s suffering at arm’s length. But he was interested in more than scoring points for the home team. He saw a life in the balance—a little four-year-old girl whose mommy and daddy loved her very much. He did not care to be “right”—he cared about saving her life.

And his insight cut my hardening heart and made me alive again. I did move to Iraq to help people. I did not move to Iraq to say no. I was convinced that I could make a difference, and I intended to say yes as often as I could.

Jessica always says, “You catch more bees with honey than vinegar.” He clearly believed the same thing. I reversed my answer. He disarmed me, and I said, “Yes!”

A few days later I was back in the hotel lobby to meet with the cousin and read the medical reports. I had no idea what I was doing. I couldn’t read a medical report to save my life. I didn’t have a background in social work. I was a complete novice.

As the cousin walked through the door of the café, my heart melted. He had brought his little girl with him—the best decision he could have made. When I saw her, I thought of my little brown-eyed girl, Emma. Was there anything I wouldn’t do to save her life? How many doors would I knock on? How long would I beg? To what degree would I debase myself to see her live?

I was a goner before the meeting ever began.

I stood up to greet the man—a kindhearted father a few years my senior. He was shorter than I; I think he had a mustache. He was gentle, respectful, and very guarded, as though a single misstep on his part could cost his daughter her life.

I realized how little I understood about the world, about power distribution, and about how it feels to be completely at the mercy of another.

It’s amazing how many thoughts can go through your mind in a few minutes. As I think back on that meeting, I have this image of myself begging on the street corner for money to pay for my daughter’s surgery. I don’t think I’ve ever done anything altruistic in my life. Everything I do is probably motivated by some sense of guilt or out of a desire to stave off my own demise. It is hard for me to ascertain whether I was compelled to help this dear man because I saw him in need or because I conjured up an image of myself in need.

We regularly tell one another to “put yourself in their place” or “walk a mile in their shoes.” I saw myself standing in his shoes, on the corner, begging for change with my little girl in my arms. I was terrified. But I don’t think I was terrified primarily for him. I think I was terrified for myself.

Whatever the case, I was moved by the idea that this little girl could die without someone who would take the risk and intervene. And I knew I would want someone to take a risk for me if I was the one holding my Emma in search of surgery.

The medical reports were unclear to me. The field of pediatric cardiology was nonexistent in Iraq as a subspecialty at that time. My impression was that she had a hole in her heart. That sounded bad enough to get my attention—it seemed reasonable enough to assume that major organs were not supposed to have extra holes in them. If the reports had been more technically accurate, they would have flown over my head altogether. But the idea of this little princess struggling to walk and play and breathe because of a life-threatening hole in her heart was enough to inspire me to jump in with both feet.

I had not named it yet—that passion and joy that caused me to suspend my questions and fears. My military friends had mantras like “Better to be judged by twelve than carried by six” and “Shoot first; ask questions later.” But I had watched Iraq destroy nearly all the people who allowed themselves to live in a constant state of suspicion or cynicism. So I adopted my own motto: “Love first; ask questions later.” Today I call it preemptive love.

Nothing had changed in my actual capacity to help this dear family. I still wasn’t a doctor. I still didn’t know anything about sending children abroad for treatment. I was wealthier than he was, but I still didn’t have enough money to pay for her surgery on my own. And my team was still focused on helping war widows—not medical treatment for children. What had changed was my heart. I moved from a policy of risk management and calculated charity to a way of life that seemed much more like the Jesus I had grown up hearing about on my nona’s lap as my nono preached from the Bible.

I promised to take the medical reports and knock on a few doors and make a few phone calls to friends. If I had one thing, it was a network of foreigners who might have access to better information than I. But I also made one more promise: I looked the father in the eyes and promised him that I would fail; I promised him that I was not going to be the one to turn up any results.

This may seem like a strange, even cruel thing to promise. But I had seen enough good intentions during my brief time in Iraq to know that good intentions are not enough. I had seen Americans swoop in and promise the moon and then fail to deliver. They always meant well. I wanted to help. But I did not want to be one more person to make promises that I could not keep. So I did the opposite.

Underpromise, overdeliver.

He gave me the medical files and a CD of data in a manila envelope. I imagine he went home and celebrated with his family. This was the closest they had come yet to saving their daughter’s life. I hoped his family looked at him differently that night—with pride and with confidence that he could get the job done to protect and provide.

Deep down, I hoped that helping this little girl would cause Jessica to look at me again with pride and trust that I could protect and provide for our family. After the rush of emotions wore off, helping this little girl became a mostly perfunctory task for me. I still had Hollywood visions of lifesaving, and this did not fit the bill. I was younger and more naive than I am now, and I did not yet realize that paperwork saves lives. Police officers save lives. Firefighters save lives. Surgeons save lives. But people who push paper around? Well, I would do what was required of me, but I certainly did not see it as a task that was likely to make much of a difference.

As I made my inquiries of foreigners in the community who were experts in their fields, I started learning shocking details and claims about the legacy of birth defects in Iraq. Every major Iraqi community had a different story to account for the apparently high rate of birth defects. Still, their stories from north to south and across ethnic and religious lines had one thing in common: almost everyone interpreted their sick and malformed children through the lens of various violent acts that were done to them by “the evil other”—that sometimes-hard-to-define group of people who are, at their core, not like us. Almost all my interviews and encounters flatly ignored the more mundane factors and known causes that are common worldwide. Instead, most derived a cathartic sense of meaning for their child’s sickness by concluding it was a result of war and violence.

And this was not without good cause, as I would learn in coming months.

I had recently met a guy named Cody who worked for a different field office—the Halabja office—inside our broader relief and development organization. He was fresh off the plane from California. I remember thinking he was both daring and perhaps a bit of a pie-in-the-sky dreamer when I saw him walking around with a book of poetry in the language of the local greats.

Surely he can’t read that? Hmph. Show-off!

The details of what happened next are a little hazy. But we don’t always know the major junctions at which our lives will change. I must have been casually getting to know Cody and the work they did all the way out there in the Halabja office. Knowing Cody the way I do today, I can guess that he probably gave me some impassioned sermon about rehabilitating people still suffering from Saddam’s chemical bombardment in 1988.

Saddam’s chemical bombardment of Halabja in 1988? My mind trailed off as Cody talked. I could not recall that I had ever heard anything about it. It is only now in retrospect that I can understand how ignorant and offensive that is to my Kurdish friends. At the time, however, it simply wasn’t on my radar. Unlike many of my colleagues (including my wife, who studied the events in graduate school), it was not a factor that compelled me to feel compassion for the Kurds, nor did it cause me to move to Iraq in hopes of making a difference. I vaguely remember Jessica’s late-night retellings of Saddam’s atrocities as she would read her books or verbally process the mind-blowing lecture of the day by Dr. Marc Ellis at Baylor University. But the gassing of Halabja never got under my skin—never seeped into my soul—the way it did for others. I was busy studying theology at the time.

Then Cody mentioned something about trying to help children with heart defects. He had my full attention.

I told him the story of my encounter with the little girl in the hotel lobby, and Cody began to connect me with others on his team who had a little more experience helping kids with broken hearts. He snowed me under with a lot of things that I didn’t understand—something about collecting medical files from across the region and sending them out to doctors in Jordan for evaluation. He mentioned a desk in their office that was piled up—his hand went above his eyes like an elevator—with reports from hundreds of children who were waiting in line for lifesaving heart surgery.

Waiting in line . . . I’ve never had to wait in line for much of anything. I’ve waited in a waiting room before. But I had an array of Highlights magazines and a comfy-enough chair to sit in at least. I’ve waited on hold with the credit card company while I flipped through an array of television stations. I’ve waited for food at fancy restaurants—but I always had a reservation for the table itself before my wife and I even arrived. There were a number of times in Austin, Texas—the Live Music Capital of the World—when I waited in line for a concert, but I already had my tickets in hand. My entrance was guaranteed. I’ve never truly waited in line the way these mothers and fathers did.

At that time, there were few diagnostic tools available in Iraq. Most cardiologists and pediatricians in the country—particularly in the Halabja region, where Cody worked—were diagnosing heart defects blindly with a stethoscope while the rest of the developed world was using ultrasounds, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT) scans, and catheterizations. There are a few phenomenal doctors out there who can perceive anatomical malformations by placing an ear on a child’s chest, but there is nothing like a qualified doctor really seeing a problem when it comes time to solicit support to save your child’s life.

Most doctors in Iraq never really knew what was wrong with their heart patients. In spite of the fact that there are scores of distinct heart defects and defect combinations, the vast majority of the population still says their child has a “hole in her heart”—a product of each doctor’s inability to truly see and understand what was going on inside a child’s body after decades of sanctions, war, and mass exodus among the country’s most knowledgeable medical experts. Like any father or mother looking out for the interest of their family, a huge number of Iraq’s medical elite escaped Iraq as soon as they saw the writing on the wall—in the late 1970s as Saddam Hussein ascended in power and became more caustic toward Iran, in the late 1980s as Saddam bankrupted the country and ultimately invaded Kuwait, and throughout the sanctions era as children starved to death and the UN pursued its doctrine of “containment” to its most extreme ends. Many of those doctors who could escape did. Of those who stayed, many were assassinated in the sectarian divide that opened upon the fall of Saddam.

When a child’s medical report landed on the pile on the corner desk in Cody’s office, the vast majority of them simply said “needs surgery”—hardly a viable medical diagnosis upon which to base the triage of children.

So as these parents waited in line, they were not merely waiting for lifesaving surgery. They were actually waiting for a proper diagnosis, living each day with a child who couldn’t walk to school or whose skin was blackish-blue from a lack of oxygen. Obtaining a proper diagnosis was a bit like playing Russian roulette, a one-in-six chance that a child would be severe enough to catch someone’s attention and rise to the top of the waiting list. Of course, if they were “lucky” enough to actually have a heart defect that demanded immediate attention, it often meant the child was very sick and very risky. I would soon learn that these were exactly the kind of children that aid offices like Cody’s and the charitable hospitals with whom they worked were most unlikely to accept.

Paradoxically, the kinds of children that the hospitals and aid groups often prefer to help are the children who are sometimes least likely to find their way to a doctor’s office in the first place. They are the ones who have ticking time bombs in their chests that absolutely must be repaired, but they lack the blackish-blue skin and lips, the deformed finger- and toenails, or the obvious exhaustion and breathing problems that result from certain defects. When war, terrorism, and underdevelopment create an impediment to routine checkups and proper diagnoses, these preferred children are the very ones who never make it onto the list at all.

I remember the day I visited Cody’s office and saw the pile of reports. It was an overwhelming sight. I gave my manila envelope to Cody’s friend as he explained a little more about how they had to wait on the once-a-week commercial flight into and out of our city to send a stack of files to a partner organization in Jordan. There was no FedEx or DHL. In Jordan, doctors would peruse the files and select those who seemed likely to fit their final selection criteria. If there were hundreds of cases for consideration, a group of twenty would be selected to come to Jordan for a real diagnostic evaluation. It wasn’t clear to me who paid for the travel or how long it took to organize a massive trip to Jordan at a time when Jordan was claiming millions of refugees from the Iraq War. Who handled the visa applications? Who guaranteed the patients’ return to Iraq?

In any case, upon arrival in Jordan, a portion of the twenty would be found to be too risky. A few might actually be given a clean bill of health—maybe there was a misdiagnosis or a self-correction of one of the more minor defects. Those who were determined to need surgery would receive their official diagnosis and be told that the organization would try to help provide surgery for them within the coming year.

Depending on available funding, a few were taken immediately to surgery and the rest of the group returned to Iraq to sit and contemplate their lot. By my later estimations, almost all of them returned to wait in line again, regardless of what the doctors in Jordan said. If their child was too risky, then they had to keep searching for solutions elsewhere. But we also learned that a “clean bill of health” was an incredibly difficult thing to accept once you’ve resigned yourself to the idea that your child is living on the brink of death.

What if the doctors in Jordan were wrong? Is this Jordanian subterfuge because I’m Iraqi? Arab subterfuge because I’m Kurdish? My child is probably still sick—I should never give up until I find someone willing to give my child the surgery I know he needs.

Even those who were selected for surgery would often doubt the intentions of the organization or would play the field to see if there was any way to expedite the surgery through another avenue.

Why take any risks after all that we’ve seen in the last few decades?

I looked at the towering stacks of files on the desk. They reminded me of the collapsing Twin Towers on September 11, one of the driving forces that had helped land me in Iraq in the first place. It was hard to imagine someone getting on a commercial flight with a bag full of files. At once it seemed innovative and harkened back to images of the Pony Express. But what would become of those who were literally lost in the shuffle? I think I remember seeing an envelope that had inadvertently fallen under a nearby table. Was it full of receipts from last week’s team retreat? Or was there a paper inside with a photo of a blue baby stapled to it that said, “Needs surgery”? He probably wouldn’t have been offended if I asked. But what did I know about saving lives?

Firefighters, surgeons, sure . . . but people who push paper around?

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Introduction

Preemptive Love is the true story of Jeremy and Jessica Courtney and their quest to put love before all else—no matter the risk. Jeremy Courtney shares with readers the journey he took with his wife, their friends, and sometimes even their enemies in order to start the Preemptive Love Coalition (PLC). The mission of PLC is simple: save as many Iraqi children as possible who are in need of heart surgery—a prevalent problem in Iraq post-Saddam Hussein’s chemical warfare, more than a decade of sanctions, and outstanding environmental questions that many have linked to American and British weapons during the 2003 Iraq War; especially since there are few surgeons in the country willing and able to perform surgery on these gravely ill children. Faced with nearly every problem imaginable, Jeremy and his community begin saving lives and seeing glimmers of peace amidst the violence and unrest of present-day Iraq.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. The story of Preemptive Love opens with a possible theme when Jeremy says on page 9, “it can be so difficult to see things for what they are; even more to see what they could be.” Discuss this quote in light of the story. How does this reflect the mission of the Preemptive Love Coalition?

2. Jeremy and Jessica coming to grips with life without electricity in Iraq sets the stage for what would soon become their “preemptive love” way of life. Discuss the conclusion from page 9, “We don’t need power to live in peace,” and the various ways it challenges your assumptions about life in the midst of war, in marriage or the workplace, and life in general.

3. The story of the Courtney family is extraordinary and heroic, but in many ways, Jeremy shares how he is just like all of us. On page 14, he says, “everything I do is probably motivated by some sense of guilt or out of a desire to stave off my own demise.” Is this feeling true for most of us? Do we often want to partake in charity out of a sense of guilt or fear? Explain your answer.

4. Preemptive Love is full of surprises, from unlikely friendships to unfailing faith even in the presence of great danger. What surprised you the most in this story?

5. Did Jeremy’s description of contemporary Iraq give you a new perspective on the situation there? Why or why not?

6. Discuss the irony of the Grand Sheikh’s decree: “we must stop this treatment lest it lead our children and their parents to love their enemies, leading to apostasy” (p. 67). Can you think of a similar irony that exists in the United States?

7. Jeremy Courtney introduces us to so many sick children in the book; some recover, others do not. Which child’s story touched you the most and why?

8. Revisit Kadeeja’s story beginning on page 122. What lessons can we glean from it? Why was Kadeeja’s father able to overcome his distrust of the Turkish doctor?

9. “Presence is sometimes a greater expression of preemptive love than any bold action or program” (p. 136). Reflect on a time you were “present” or someone was “present” for you. Do you agree with Jeremy that “presence is . . . a greater expression of preemptive love than any bold action” during difficult times? Why or why not?

10. Do you think that Rizgar’s ten-year journey away from home as a child, and his subsequent return as an adult, was a matter of fate or luck? In what ways do you think his time away from home helped shape his work with the Preemptive Love Coalition?

11. Mustafa proudly displays his tattered soccer ball after his surgery, showing Jeremy and his team that miracles can happen. What do you think this soccer ball might be a metaphor for in Mustafa’s life? What about for Jeremy and his friends? What “soccer ball” do you have in your life?

12. Why do you think that Rizgar chose to go to prison rather than use the “Get Out of Jail Free” card offered to him in exchange for information on Jeremy Courtney and his family? Consider this in juxtaposition to his later choices, and discuss how real people can sometimes be at once a friend and an enemy. How have you seen this in your own family, workplace, etc.?

13. On page 226 Jeremy quotes the Aeneid: “I fear Greeks, even those bearing gifts.” How does this quote connect to the story of the Preemptive Love Coalition?

14. Discuss the afterword. On what note does this story end? What impression do you have for the future of the Preemptive Love Coalition and what they’ll be able to accomplish with their efforts?

15. How has reading this book affected you? In what ways are you inspired to reexamine your life and your presuppositions about people? How will this change the way you approach others going forward?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Jeremy Courtney gave a TED talk on November 12, 2011, about preemptive love and the concept of unmaking violence and remaking the world through healing. Gather with your reading group to watch: http://www.jeremycourtney.com/tedxbaghdad.

Over dinner, discuss Jeremy’s message. How does his story touch you? How can you make a difference in your world? What is the greatest lesson that Jeremy’s story teaches you?

2. Jeremy shares his approach to adapting to life in Iraq: “for the first six months, we say 'yes' to everything” (p. 80). Try this radical way of being in the world for one week. Afterward, meet as a group and discuss the results. What was it like to say “yes” for an entire week? How was it different than a typical week for you? Why do you think that Jeremy takes this approach in Iraq? In his life in general?

3. On page 184, Jeremy mentions the Robert Frost poem “The Road Not Taken” in order to explain the way that he and Jessica choose to live their life. Read the poem out loud (http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173536) to your group, and discuss the ways in which the poem enacts the very tenets of faith, love, and joy that distinguish the Courtney family and the Preemptive Love Coalition.

A Conversation with Jeremy Courtney

1. In many ways, this is the story of your life, and as such, it is a work in progress. Why did you decide to begin Preemptive Love with the story of you drinking chai in an Iraqi Hotel? To your mind, what makes this moment the defining moment of the Preemptive Love Coalition?

I am not sure I would say it was the defining moment. Your point about being a work in progress is exactly right. I could have just as easily started with lying on my grandma’s lap three or four times a week as my grandpa preached and my father led the church in worship. In many ways, the story seems to begin for me when I went off to college and wrestled with nearly every aspect of life and faith as I had received it and understood it up until that time. September 11 was certainly a defining moment for so many in my generation—some of us went one direction and some of us another with regard to how we would live in a world full of evil.

But I began the story drinking chai in an Iraqi hotel, because the rest of the story lacks meaning without presence. The hotel scene establishes a few things: (1) our intentional proximity to suffering and need; (2) my conflicted, less-than-heroic response; and (3) my personal introduction to the utter lack of options for children born with life-threatening heart defects in Iraq.

2. What surprised you most about living in Iraq? What has been the best part about your life there? The most difficult?

As with any place in the world, I’d guess all three of these questions have the same answer: people. The people here are complex, and that surprised me, honestly. I was reared on a relatively simple story about Arab backwardness, corruption, etc. Some of my first Muslim friends in my twenties were Turks and Kurds, and there was no love lost between them and the Arab Muslims who would soon be my neighbors in Iraq. So from all quarters, I entered Iraq with a story and a set of expectations that did not incline me to love. On the bright side, my negative perceptions primed me for the best possible response every time I saw an Iraqi break my simple mold. Their love for their children, their earnest desire for peace, their ingenuity to make it through another day—let alone so many prolonged seasons—of violence . . . all these things surprised me and caused love to well up in my heart for the people around me.

The best part of my life in Iraq has been the people. Both the individuals and society as a whole have enriched my understanding of God, my capacity to show honor and respect to others, my self-awareness, my confidence and humility about my place in the world, and my ability to be a better husband and father.

At the same time, the most difficult part of my life in Iraq has been . . . the people! Iraq would be problem-free if it weren’t for all the people! But then, the same could be said for any nation, organization, or family. It seems to me that there is a direct correlation between the level of risk in relationships and the amount of joy derived from them. The people we endeavor to love the most become the ones who are most capable of destroying us. In the end—and I recognize that this may not be true for everyone in Iraq—it was not the suicide bombers, the militias, or the violent clerics who posed the greatest threat to us. It was those who were much closer, whom we loved even more, and allowed to get even closer. And, ultimately, that is why I think preemptive love—and this book—is about relationships, and not primarily about Iraq.

3. When the fatwa came out against you, you write that you sent an email to your team inviting them to your house to pray. Can you share with us the power of prayer in your life? Has prayer been a defining part of your life in Iraq?

There is a part of me that deeply wants to impress you with a mind-blowing answer of personal piety right now. But that part of me is vain and dishonest. The truth is that I have a sort of “love-hate” relationship with prayer—especially with prayer as a means of asking God to do what I imagine God already wants to do. I do not mean to say that I am justified or right in this way of thinking, but that kind of prayer has always confused me and left me wondering why I would worship one so capricious.

While I think it is probably clear from the story that I believe in the existence, the presence, and the here-on-earth activity of God, I often struggle to live at this intersection of belief and doubt, where, on the one hand, I engage in prayer as a form of work because God has decided that the restoration of some things on this earth will depend on me and, on the other hand, I rest from work, even prayers of supplication and intersession, because of a bedrock conviction that God is ultimately in control and is far more concerned than I am with the well-being of my neighbors, the environment, war, peace, and God’s own great name.

But there is at least one kind of prayer that has had a profound impact on me during my time in Iraq, and that is prayer as imagining, prayer as dreaming. This can be a spur of the moment thing while driving in chaotic Baghdad traffic waiting for the next bomb to go off, or an extended morning of quiet meditation. In both extremes, the content is essentially the same, and it goes something like this: “God, give me your vision for this country; this city; this guy I’m sharing tea with right now.”

That prayer resonates within me, because even while it is about Iraq, it recognizes a deficiency in myself that must change before I should expect to be let in on such treasure. This was the essence of my prayers after the fatwa came out. We said, “We already know the broad definition of our response. And we trust, God, that you have a plan in the midst of violence and chaos. So let us in on your envisioned future . . . what good things could we bring about here—and what evil things could we dismantle—as we submit ourselves to loving our enemies?”

4. You describe the difficulty of Baby Hope’s death after surgery and the struggle to comfort grieving parents. What was it like for you personally in that moment? Was this the most difficult moment you had to face so far?

It was absolutely horrible. We had to grow up quickly in a lot of ways. I had just moved us from being a sort of distant, third party financier of other people’s decisions and operations. With Hope, I made the call. I selected her for surgery, I chose the hospital, I signed off on the doctor. I was in the hot seat, in a highly contentious time in Iraq, among a people that still demand extortionary financial remuneration, or even blood for blood, in the wake of death. There are no insurance policies or lawyers to shield you in a time like this. But, to my surprise, those self-referential concerns were not anywhere near the top of my list. I’ve only learned over time to give consideration to those things. In the moment of Hope’s death, the only thing I could think of was Yusuf, his wife, and their irreplaceable loss. I felt a deep sense of responsibility for that and wondered how many more losses we would have to endure on our way to reaching all the children we had promised to help.

In those crisis moments you form a special bond. But what I’ve had to learn is that those relationships (for the most part) cannot last—they are simply too painful for the parents. The trust formed is great. And we’ve heard repeatedly that our responses to their suffering are often much more sensitive and comforting than many of the responses they receive from their own families and friends. But, at the end of the day, for most of these families who endure their greatest losses at our hands, they cannot stand to see us hovering around each week reminding them of hope gone wrong. They never “move on,” of course, but they eventually relegate us from status as “friend” to “service provider” so they can cope with their losses and begin to put their life back in order. For us, the loss of that friendship becomes the second great loss after a child dies.

5. Do you hope to break any stereotypes with this book?

Absolutely! But if I have to name them, I’m probably not doing a very good job as a storyteller!

6. The complications of different cultures arise frequently in the story. If you could go back in time and change one decision you made, what would it be and why?

I refuse to live in the past or entertain any notion of “wasted years.” There are no wasted years, at least, not in the past. The only wasted years are in the future, and they are only wasted if we refuse to learn from our past. So, looking to the future, I have been much more determined to empower my colleagues on the ground to make the real-time decisions they deem best in order to keep themselves safe and enable PLC to continue its mission. If I cannot trust my team to make wise decisions, then they probably should not be a part of the team at all. If they are a part of the team, then they need to be free to read the situation around them and make the decisions required, in keeping with our vision and values.

7. Preemptive Love depicts a part of life in Iraq that we don’t often see in popular culture; that is, ordinary, everyday existence. Was it important to you to present an alternative point of view?

Presenting everyday Iraqis in their own hues has been a central part of what we have tried to do since moving here in the middle of the war when “everyday Iraqis” began to destroy my black-and-white vision of war and its various justifications. YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and their various copycats were all new technologies that came into their own during the Iraq War. In an age of institutionalized propaganda on all sides of the conflict stood a great opportunity to walk against the current with a more nuanced message about Iraqis, Arabs, and Muslims, in general. For some groups, the offending perspective is that we would portray Muslims in a positive light, making them the heroes of this story; for others, that we would call a spade a spade and name Islam and some of its clerics as the principals responsible for so much evil throughout Iraq.

8. What would you name as the theme of the story? What do you hope readers will learn by reading your book?

I was an unbearable partner in the process of writing the subtitle and designing the cover, because I am so resistant to any attempt to reduce the story to a single, isolated theme. If we say the story is about “unmaking violence” or “dismantling fear” or “overcoming hate,” I am insistent that the story is even more about remaking the world through healing, building bonds of friendship in the midst of conflict, and creating an entire realm in which love of self is seen as inextricably tied up with love of neighbor and love of enemy. But even if you will allow all those previous themes to stand as a single descriptor, I cannot allow them to stand as primarily human pursuits, divorced from God, creator of the world, animator of life. That story is the story of a faith relegated to the “far country”—a sort of “by and by” existence that seems so distant so as to not have any bearing on life in this country today. I don’t believe in that story.

Our story doesn’t exist apart from the faith that energizes and causes it to happen. So it is a story about following Jesus and living with the kind of faith that dares to believe in destroying death and the works of the devil and joining God in the beautiful restoration of all things. And that makes it a story about journeying “through many valleys, toils, and snares” on our way to that far country, only to find that it has already arrived.

I hope readers will learn the same thing I hoped to codify for my family in writing it: try to save your life, and you are sure to lose it. Give your life away, and you will save it.

9. On page 221 you discuss the robbery at your home, citing that “the other thing missing after that fateful invasion was our hope of ever fully trusting another person in Iraq the same way again.” Did your trust ever return? Is trust in humankind something you think can be returned to you?

I liken the break-in and that entire season of betrayal to a soul-rape. There was an innocence that was stolen, and things can never be returned to their previous state. But that inability to trust in exactly the same way again does not necessarily have any decisive bearing on how we choose to live. Do we trust people outside of our immediate “circle of sameness” the same way we trusted outsiders before? Probably not. But we still choose to entrust our lives to them over and over again, come what may (and if there is one thing we have seriously considered by now, it’s what may come). The book is peppered with the cautions of others who call this way of living naive. Other people’s opinions of us are really none of our business. From our perspective, it is equally naive to pretend that armored cars, flack jackets, guns, tactical attack plans, and counter-insurgency theories represent the surest, safest way to live.

10. Why did you decide to write this story now? Describe the journey from conception to publication.

The impetus really came after a number of conferences where I spoke and people asked for anything I had written that could help them understand what was meant by this provocative phrase “preemptive love.” This is still not that book. I hope to write that book at some point in the future. On my way to writing that book, however, I felt like our foundational story needed to be written to provide some kind of context for the theological and philosophical explanations that might follow.

My friend, Gabe, was kind enough to put me in touch with his literary agent, and I was humbled that Chris agreed to invest some of his time into the story and represent me to publishers across the country. Chris ran interference for a couple of interested parties, and we entertained a few offers on the book before settling on Howard.

I felt an instant connection with the team at Howard and was very humbled to hear their vision for the book, which aligned very closely with my own. We were talking the same language from the beginning, and that gave me hope for a very great partnership (which it has been!).

Throughout the fall of 2012, we actually took a semester-long break from Iraq to be present for the birth of Cody and Michelle’s first child. But that same stretch of time was our busiest ever with surgical teams coming into Iraq to save lives and train Iraqis. So I was back and forth from the States to Iraq every few weeks with a surgery team. When I wasn’t at the hospital, I was holed up in a hotel room in Istanbul, Najaf, or Basra, writing as much as I could. I found that I am a significantly more focused person on the road than I am trying to write from my in-laws’ kitchen table with “life” happening all around me!

In all, it has been an incredible, humbling experience. We don’t deserve to have this story told. It would have been meaningful enough to have experienced it without much ado. But if this strange, media-saturated world we live in is willing to take a risk on an idea to put before the world, we are grateful that this risky message of preemptive love would rise to the top for this short moment in time. We will take the stage while we have it, however big or small, in hopes of unmaking violence and remaking the world, one heart at a time.

Keep up with or get in touch with Jeremy and PLC:

Facebook: www.facebook.com/TheJCourt

Twitter: www.twitter.com/JCourt

Email: jeremy@preemptivelove.org

Phone: 806-853-9131

Product Details

- Publisher: Howard Books (September 2, 2014)

- Length: 240 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476733654

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Courtney gives an honest, and at times poignant, account of his efforts to establish the Preemptive Love Coalition in Iraq. Courtney relates his riveting story through the inner thoughts of both patients and adversaries, describing events like the chemical bombing of Halabja and the attack of a roadside bomber from a personal perspective. . . . powerfully inspiring, touching, and, unfortunately, urgently relevant." —Publishers Weekly

– Publishers Weekly

"There’s enough intrigue, betrayal, death, bombings, and more to fill a blockbuster novel, but this is not fiction. It’s a 'warts and all' look at Christianity in action in the trenches, an honest, unflinching look at the cost of living out what you believe. Complacent Christians be warned: this is not just a book, it’s a wake-up call. How many of us are bold enough to 'Love first. Ask questions later'? That is the challenge of Preemptive Love." —Crosswalk.com

– Crosswalk.com

“The story of Preemptive Love is so awe-inspiringly powerful it could rewrite the hardwiring that holds humanity hostage. Our perpetual fears and resulting violence stunt evolution; we are a primitive species, still. But Jeremy and his Preemptive Love cohorts are lights revealing humanity's greater, true self. As living, breathing examples of agape they raze the walls that blind and divide us.” —Greg Barrett, journalist and author

– Greg Barrett, journalist and author

“Preemptive Love is a story of caring for and bringing healing to those who have suffered violence and war. Jeremy Courtney clearly identifies the need for compassion and forgiveness; spreading this message is his mission. He has shown his love and generosity to many of Iraq's neediest children. Jeremy is moved by faith and acts with grace and love.” —Imam Mohamed Magid, Imam of ADAMS Center Virginia and President of Islamic Society of North America

– Imam Mohamed Magid, Imam of ADAMS Center Virginia and President of Islamic Society of North America

“In Preemptive Love, Courtney deftly chronicles his journey to help children obtain life-saving surgeries in battered regions where hospitals had long been gutted and clinics closed. In the process, he finds that his family’s strategy of defeating hate and prejudice with unconditional love heals hearts beyond the ones he set out to fix. Courtney’s moving story gives us some of the best news to come out of Iraq in ages.” —Lorraine Ali, Los Angeles Times

– Lorraine Ali, Los Angeles Times

“I'm a cynic. I have to be in my line of work. But the world of cynicism isn't one in which Jeremy and Jessica inhabit. And Iraq's broken children are all the better for it. . . . I am also a die-hard agnostic. And while Courtney writes of his faith as a powerful motivating factor in what he does, he doesn't preach. This is just one man's journey, told from the heart. What Preemptive Love is, above all else, is a book of adventure, tragedy, suffering and hope, and the incredible and indomitable power of human compassion. . . . A thoroughly gripping and moving tale of what motivates one group of people to help the children who suffered the most in Iraq.” —Alex Hannaford, journalist (GQ, The Atlantic, Esquire); author, Last of the Rock Romantics

– Alex Hannaford, journalist (GQ, The Atlantic, Esquire); author, Last of the Rock Romantics

“Jeremy Courtney is doing some of the most redemptive work on the planet, providing life-saving surgeries for Iraqi children. Their motto, ‘Love now, and ask questions later,’ is a brilliant critique of preemptive war. Jeremy has become a close friend over the years, and many of us have been waiting for this book like kids on Christmas morning. From TED talks,to megachurches, to Congress and the UN, Jeremy's message that 'Violence unmakes the world, and love remakes it' has been transforming hearts and minds. Now that message is in your hands. Share it with the world.” —Shane Claiborne, author, activist, and preemptive lover, www.thesimpleway

– Shane Claiborne, author, activist, and preemptive lover, www.thesimpleway

“Jeremy Courtney's story, and that of the Preemptive Love Coalition, will help you redefine and reimagine what love really means. Preemptive Love will inspire you to dream of a love that risks everything. It is the kind of story and radical surrender the world is longing to see in those who profess to love like Jesus.” —Ken Wytsma, founder of The Justice Conference, author of Pursuing Justice, president of Kilns College

– Ken Wytsma, founder of The Justice Conference, author of Pursuing Justice, president of Kilns College

“Compelling! While the rest of us fold our arms and complain about the situation in the Middle East, Courtney proves that one family can begin an avalanche of change.” —Leigh Saxon, coordinator of Mission Waco/Mission World Health Clinic

– Leigh Saxon, coordinator of Mission Waco/Mission World Health Clinic

“Preemptive Love is a beautiful and inspiring book about the power of love in a time of war, and the capacity of personal interactions, based on love, to break through all the geopolitical strategizing and local suspicions to build trust and, in the case of Jeremy and Jessica Courtney, to save lives.” —Joseph Lieberman, former US Senator, author of The Gift of Rest

– Joseph Lieberman, former US Senator, author of The Gift of Rest

“Jeremy Courtney weaves the compelling, true story of grace in the midst of violence! He and his colleagues risk touching the pain of Iraqi children plagued by heart defects and their families who scramble to get care for them. They all risk betrayal in order to achieve healing. In the process, they discover opportunities for releasing love and hope into a torn world.” —Sister Simone Campbell, executive director of NETWORK, founder of Nuns on the Bus

– Sister Simone Campbell, executive director of NETWORK, founder of Nuns on the Bus

“This is a wonderful book with a powerful, time-tested message: love wins. But Jeremy Courtney and his wife aren’t just writing about love in theory or theology. They are showing us all the power of God’s love in practice evidenced through the love of His people for others very different than themselves. As a former US diplomat and Ivy League professor I highly recommend this book. But more importantly, as a human being looking for God’s love in this war-torn and weary world, I thank God for this book.” —The Honorable Gregory W. Slayton, author of national bestseller Be a Better Dad Today

– The Honorable Gregory W. Slayton, author of national bestseller Be a Better Dad Today

“I could not put this book down. Preemptive Love brings you to the streets of Iraq and into the hearts of children, shouting the powerful message that love has the capacity to remake our world.” —Peter Greer, President and CEO, HOPE International, and author, The Spiritual Danger of Doing Good

– Peter Greer, President and CEO, HOPE International, and author, The Spiritual Danger of Doing Good

"Jeremy Courtney is a prophet who has undertaken the task of reminding those of us discouraged by the brokenness and fear of this world to choose something Greater. Courtney believes in a Real World, the kind of world God always intended for us, one that right now, in the midst of violence and hate, is being remade by Love. And, like a true prophet, he invites us to join him in the remaking." —Micha Boyett, author of Found: A Story of Questions, Grace and Everyday Prayer

– Micha Boyett, author of Found: A Story of Questions, Grace and Everyday Prayer

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Preemptive Love Trade Paperback 9781476733654

- Author Photo (jpg): Jeremy Courtney Photograph by Abigail Criner(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit