Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

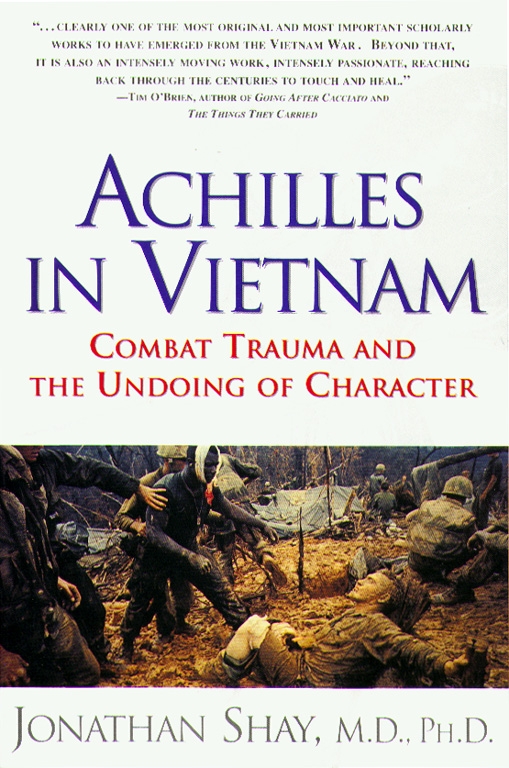

About The Book

In this moving and dazzlingly creative book, Dr. Jonathan Shay examines the psychological devastation of war by comparing the soldiers of Homer’s Iliad with Vietnam veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. A classic of war literature that has as much relevance as ever in the wake of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Achilles in Vietnam is a “transcendent literary adventure” (The New York Times) and “clearly one of the most original and most important scholarly works to have emerged from the Vietnam War” (Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried).

As a Veterans Affairs psychiatrist, Shay encountered devastating stories of unhealed PTSD and uncovered the painful paradox—that fighting for one’s country can render one unfit to be a citizen. With a sensitive and compassionate examination of the battles many Vietnam veterans continue to fight, Shay offers readers a greater understanding of PTSD and how to alleviate the potential suffering of soldiers. Although the Iliad was written twenty-seven centuries ago, Shay shows how it has much to teach about combat trauma, as do the more recent, compelling voices and experiences of Vietnam vets.

A groundbreaking and provocative monograph, Achilles in Vietnam takes readers on a literary journey that demonstrates how we can learn how war damages the mind and spirit, and work to change those things in our culture that so that we don’t continue repeating the same mistakes.

Excerpt

Betrayal of "What's Right"

Every instance of severe traumatic psychological injury is a standing challenge to the rightness of the social order.

Judith Lewis Herman,

1990 Harvard Trauma Conference

We begin in the moral world of the soldier -- what his culture understands to be right -- and betrayal of that moral order by a commander. This is how Homer opens the Iliad. Agamémnon, Achilles' commander, wrongfully seizes the prize of honor voted to Achilles by the troops. Achilles' experience of betrayal of "what's right," and his reactions to it, are identical to those of American soldiers in Vietnam. I shall describe some of the many violations of what American soldiers understood to be right by holders of responsibility and trust.

Now, there was a LURP [Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol] team from the First Brigade off of Highway One, that looked over the South China Sea. There was a bay there....Now, they saw boats come in. And they suspected, now, uh -- the word came down [that] they were unloading weapons off them. Three boats.

At that time we moved. It was about ten o'clock at night. We moved down, across Highway One along the beach line, and it took us [until] about three or four o'clock in the morning to get on line while these people are unloading their boats. And we opened up on them -- aaah.

And the fucking firepower was unreal, the firepower that we put into them boats. It was just a constant, constant firepower. It seemed like no one ever ran out of ammo.

Daylight came [long pause], and we found out we killed a lot of fishermen and kids.

What got us thoroughly fucking confused is, at that time you turn to the team and you say to the team, "Don't worry about it. Everything's fucking fine." Because that's what you're getting from upstairs.

The fucking colonel says, "Don't worry about it. We'll take care of it." Y'know, uh, "We got body count!" "We have body count!" So it starts working on your head.

So you know in your heart it's wrong, but at the time, here's your superiors telling you that it was okay. So, I mean, that's okay then, right? This is part of war. Y'know? Gung-HO! Y'know? "AirBORNE! AirBORNE! Let's go!"

So we packed up and we moved out.

They wanted to give us a fucking Unit Citation -- them fucking maggots. A lot of medals came down from it. The lieutenants got medals, and I know the colonel got his fucking medal. And they would have award ceremonies, y'know, I'd be standing like a fucking jerk and they'd be handing out fucking medals for killing civilians.

This veteran received his Combat Infantry Badge for participating in this action. The CIB was one of the most prized U.S. Army awards, supposed to be awarded for actual engagement in ground combat. He subsequently earned his CIB a thousand times over in four combat tours. Nonetheless, he still feels deeply dishonored by the circumstances of its official award for killing unarmed civilians on an intelligence error. He declares that the day it happened, Christmas Eve, should be stricken from the calendar.

We shall hear this man's voice and the voices of other combat veterans many times in these pages. I shall argue throughout this book that healing from trauma depends upon communalization of the trauma -- being able safely to tell the story to someone who is listening and who can be trusted to retell it truthfully to others in the community. So before analyzing, before classifying, before thinking, before trying to do anything -- we should listen. Categories and classifications play a large role in the institutions of mental health care for veterans, in the education of mental health professionals, and as tentative guides to perception. All too often, however, our mode of listening deteriorates into intellectual sorting, with the professional grabbing the veterans' words from the air and sticking them in mental bins. To some degree that is institutionally and educationally necessary, but listening this way destroys trust. At its worst our educational system produces counselors, psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists who resemble museum-goers whose whole experience consists of mentally saying, "That's cubist!...That's El Greco!" and who never see anything they've looked at. "Just listen!" say the veterans when telling mental health professionals what they need to know to work with them, and I believe that is their wish for the general public as well. Passages of narrative here contain the particularity of individual men's experiences, bearing a different order of meaningfulness than any categories they might be put into. In the words of one veteran, these stories are "sacred stuff."

The mortal dependence of the modern soldier on the military organization for everything he needs to survive is as great as that of a small child on his or her parents. One Vietnam combat veteran said, "The U.S. Army [in Vietnam] was like a mother who sold out her kids to be raped by [their] father to protect her own interests."

No single English word takes in the whole sweep of a culture's definition of right and wrong; we use terms such as moral order, convention, normative expectations, ethics, and commonly understood social values. The ancient Greek word that Homer used, thémis, encompasses all these meanings. A word of this scope is needed for the betrayals experienced by Vietnam combat veterans. In this book I shall use the phrase "what's right" as an equivalent of thémis. The specific content of the Homeric warriors' thémis was often quite different from that of American soldiers in Vietnam, but what has not changed in three millennia are violent rage and social withdrawal when deep assumptions of "what's right" are violated. The vulnerability of the soldier's moral world has increased in three thousand years because of the vast number and physical distance of people in a position to betray "what's right" in ways that threaten the survival of soldiers in battle. Homeric soldiers actually saw their commander in chief, perhaps daily.

AN ARMY IS A MORAL CONSTRUCTION

Book 1 of the Iliad sets the tragedy in motion with Agamémnon's seizure of Achilles' woman, "a prize I [Achilles] sweated for, and soldiers gave me!" (1:189) We must understand the cultural context to see that this episode is more than a personal squabble between two soldiers over a woman. The outrageousness of Agamémnon's behavior is repeatedly made clear. Achilles' mother, the goddess Thetis, makes her case to Zeus: "Now Lord Marshal Agamémnon has been highhanded with him, has commandeered and holds his prize of war [géras, portion of honor]...." The prize of honor was voted by the troops for Achilles' valor in combat. A modern equivalent might be a commander telling a soldier, "I'll take that Congressional Medal of Honor of yours, because I don't have one." Obviously, Achilles' grievance was magnified by his attachment to the particular person of Brisêis, the captive woman who was the prize, but violation of "what's right" was central to the clash between Achilles and Agamémnon.

Any army, ancient or modern, is a social construction defined by shared expectations and values. Some of these are embodied in formal regulations, defined authority, written orders, ranks, incentives, punishments, and formal task and occupational definitions. Others circulate as traditions, archetypal stories of things to be emulated or shunned, and accepted truth about what is praise-worthy and what is culpable. All together, these form a moral world that most of the participants most of the time regard as legitimate, "natural," and personally binding. The moral power of an army is so great that it can motivate men to get up out of a trench and step into enemy machine-gun fire.

When a leader destroys the legitimacy of the army's moral order by betraying "what's right," he inflicts manifold injuries on his men. The Iliad is a story of these immediate and devastating consequences. Vietnam has forced us to see that these consequences go beyond the war's "loss upon bitter loss...leaving so many dead men" (1:3ff) to taint the lives of those who survive it.

VICTORY, DEFEAT, AND THE HOVERING DEAD

In victory, the meaning of the dead has rarely been a problem to the living -- soldiers have died "for" victory. Ancient and modern war are alike in defining the relationship between victory and the army's dead, after the fact. At the time of the deaths, victory has not yet been achieved, so the corpses' meaning hovers in the void until the lethal contest has been decided. Victory -- and the cut, crushed, burned, impaled, suffocated, frozen, diseased, drowned, poisoned, or blown-up corpses -- mutually anchor each other's meaning. Homeric participants in warfare understood a very simple relationship between civilians and the soldiers who fought to protect them: In defeat, all male civilians were massacred and all female civilians were raped and carried away into slavery. In the modern world, the meaning of the dead to the defeated is a bitter, unhealed wound, where defeat rarely means obliteration of the people and civilization. As we recently witnessed in the Persian Gulf War, defeat may not even bring the fall of the opposing government. At the level of grand strategy in Vietnam, the United States had been defeated, and yet American soldiers had won every battle.

For the veterans, the unanchored dead continue to hover. They visit their surviving comrades at night like the ghost of Pátroklos, Achilles' friend, visits Achilles:

...let me pass the gates of Death.

...I wander

about the wide gates and the hall of Death.

Give me your hand. I sorrow. (23:88)

The returning Vietnam soldiers were not honored. Much of the public treated them with indifference or derision, further denying the unanchored dead a resting place.

Some veterans' view -- What is defeat? What is victory?

During a group therapy session, I once blundered into a casual mention of "our defeat" in Vietnam. Many veterans returned from Vietnam and found themselves outcast and humiliated in American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars posts where they had assumed that they would be welcomed, supported, and understood. Time and again they were assailed as "losers" by World War II veterans. The pain and rage at being blamed for defeat in Vietnam was beyond bearing and resulted in many brawls.

These feelings reflect not only outrage at the heartless wrong-headedness of such remarks but also a concept of victory in war that left Vietnam veterans bewildered. "We knew that we never lost a battle," say the veterans. Winning, as far as I have been able to determine, meant to them being in possession of the ground at the end of the battle. So the hit-and-run or hit-and-hide small-unit tactics of the enemy always meant that we had "won" after a given engagement. However, many men experienced a deep malaise that their concepts of victory, of strength embodied in fire superiority and often in great local numerical superiority, somehow didn't fit, were futile. The enemy initiated 90 percent of all engagements but "lost" them all. Even battles like Dak To and Ap Bia Mountain (Hamburger Hill) were American victories in the sense that Americans held the ground when the last shot was fired.

Larger images of victory seem to have been formed out of newsreel footage of World War II surrender ceremonies and beautiful women weeping for joy at their liberation; defeat was a document signed in a railway carriage and German troops marching in Paris. As I listen to some veterans, there are times when it seems they believe that the Vietnamese cannot have won the war. Therefore, because we won all our battles, our victory was some-how stolen. Many veterans have a well-developed "stab in the back" theory akin to that developed by German veterans of World War I -- that the war could have been handily won had the fighting forces not been betrayed by home-front politicians. My interest here is in the soldiers' experiences and not in the larger historical question of whether they were "sold out" by the politicians some-how brought under the spell of such still-hated figures as Jane Fonda.

Once or twice I have tried to explore with veterans these concepts of victory and defeat. I have abandoned these discussions, because the sense of betrayal is still too great and the equation of defeat with abandonment by God and personal devaluation still too vivid.

To return to my blunder in group therapy, a veteran whose voice is often heard in this book turned black with anger and, glaring at me, said, "I won my war. It's you who fucking lost!" He got up and left the room to remove himself from the opportunity to physically hurt me. Toward the end of the group session he returned and said, "What we lost in Vietnam was a lot of good fucking kids!"

More than a year after this experience I gingerly approached the subject with another veteran, prefacing what I was about to say (the paradox that we had "lost" the war while "winning" every battle) by saying that I knew that this was a very sensitive subject and that it made many vets very angry. When I had said it, he smiled in a not very friendly way and drew his finger across his throat. "It makes you want to cut my throat?" I asked. "Uh-huh," he replied.

DIMENSIONS OF BETRAYAL OF "WHAT'S RIGHT"

To grasp the significance of betrayal we must consider two independent dimensions: first, what is at stake, and second, what thémis has been violated.

On danger in war

"To someone who has never experienced danger, the idea is attractive," wrote the famous nineteenth-century military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. So it appeared to many young men who volunteered -- only about 10 percent of the men I see were drafted -- for military service during the Vietnam War. For some it was a way to "prove" themselves to themselves, sometimes to their fathers and uncles who were World War Ii veterans. For some it was attractive as an expression of patriotic and religious idealism, often understood to be equivalent to anti-Communism:

You get brought up with God an' country, and -- y'know, something good turned out bad....They told me I was fighting Communism. And I really believed in my country and I believed everyone served their country.

Another veteran:

It was better to fight Communism there in Vietnam than in your own back yard. Catholics had the worst of it. We had to be the Legions of God. We were doing it for your faith. We were told: Communists don't like Catholics.

For some the war was a cause that expressed an heroic ideal of human worth, in the words of one veteran, "the highest stage of mankind, willing to put your life on the line for an idea." For others it was the excitement, the spectacle of war. One veteran described his motive for joining the Marines: "I was bored. Vietnam was where it was happening, and in the Marines everybody went to Vietnam."

All knew that war was dangerous, but none were prepared for the "final shock, the sight of men being killed and mutilated [which] moves our pounding hearts to awe and pity." They went to war with the innocence built from films in which war, in Paul Fussell's words, was

systematically sanitized and Norman Rockwellized, not to mention Disneyfied....In these, no matter how severely wounded, Allied troops are never shown suffering what was termed, in the Vietnam War, traumatic amputation: everyone has all his limbs, his hands and feet and digits, not to mention expressions of courage and cheer."

Danger of death and mutilation is the pervading medium of combat. It is a viscous liquid in which everything looks strangely refracted and moves about in odd ways, a powerful corrosive that breaks down many fixed contours of perception and utterly dissolves others. Without an accurate conception of danger we cannot comprehend war and cannot properly value the moral structure of an army. We must grasp what is at stake: lethal danger and the fear of it.

The fairness assumption

Adults rightly think that a sense of proportion about petty injustice is intrinsic to maturity and hear their children shrilling. "It's not fair!" as evidence of their childishness. The culture shock of civilians entering the stratified and ritualized military world is well known. It is also the world of "chickenshit." As Paul Fussell put it:

If you are an enlisted man, you'll know you've been the victim of chickenshit if your sergeant assigns you to K.P. not because it's your turn but because you disagreed with him on a question of taste a few evenings ago. Or, you might find your pass to town canceled at the last moment because, you finally remember, a few days ago you asked a question during the sergeant's lecture on map-reading that he couldn't answer.

Civilians and noncombat veterans often equate complaints about military life to adolescent whining because of the unexamined assumption that its injustices are always of this low-stakes variety. The experiences that Fussell invokes here undoubtedly cause anger and indignation, but the essential element of mortal danger is lacking. However, Fussell, himself a World War II combat veteran, continues the passage without a change in tone:

Or, if you uttered your...[indiscretion] while in combat instead of in camp, you might find yourself repeatedly selected to take out the more hazardous night patrols to secure information, the kind, a former junior officer recalls, 'we already knew from daytime observations, and had reported.'

Because we have entered the realm of mortal danger, the experience of betrayal merits full, respectful attention. Paradoxically, the reader must respond emotionally to the reality of combat danger in order to make rational sense of the injury inflicted when those in charge violate "what's right." If the emotion of terror is completely absent from the reader's experience of this book, crucial information about the experience of combat is not getting through.

A veteran recalls,

Walking point was an extremely dangerous job. The decision on who was going to do it was so carefree, so carefree, yeah. The decision was made politically [laughs]. Most of the time politically. Certain people got the shit. Certain people didn't. Certain people on the right side of certain people.

Another veteran:

The CO had his favorites. Two companies, Delta [this veteran's company] and Charlie, always got sent out. The other two always stayed back on the hill at __.

This may sound like a child complaining, "It's not fair!" about taking turns carrying out the trash, unless one grasps what was at stake. During the course of this man's year with Delta Company, it suffered more than 100 percent casualties, taking replacements into account. The companies that were the CO's favorites suffered few casualties. Contrary to what the young men anticipated in training and in watching war films, once they encountered the reality of battle, they fervently wanted to avoid it and wanted risk to be fairly distributed. Many aspects of the thémis of American soldiers cluster around fairness. When they perceived that distribution of risk was unjust, they became filled with indignant rage, just as Achilles was filled with mênis, indignant rage.

Soldiers grow most doubtful about the fair distribution of risk when they see that their commanders shelter themselves from it. Writing of the Vietnam War, a respected military historian commented:

Officers in every, armed force must find ways of inducing their men to fight and risk their lives -- a most unnatural activity....In modern warfare, where automatic weapons, artillery, and air power impose dispersal, men can rarely be pushed into combat; they must be pulled by the prestige of their immediate leader and the officers above him. Combat expertise that soldiers recognize and personal qualities of authority are important, but so is an evident willingness to share in the...deadly risks of war.

...The deadly risks of combat must unfailingly be shared whether it is tactically necessary to do so or not, and junior officers cannot do alt the sharing.

If soldiers see that their immediate leader is exposed to risk while his superiors stay away from combat, they will be loyal to the man but disaffected from the army....In Vietnam, the mere fact that officers above the most junior rank were so abundant and mostly found in well-protected bases suggested a very unequal sharing of the risk. And statistics support the troops' suspicion. During the Second World War, the Army ground forces had a full colonel tot every 672 enlisted men; in Vietnam (1971) there was a colonel for every 163 enlisted men. In the Second World War, 77 colonels died in combat, one for every 2,206 men thus killed; throughout the Vietnam war, from 1961 till 1972, only 8 colonels were killed in action, one for every 3,407 men.

The Iliad reminds us that military and political leaders have not always been thousands of miles away from the war zone. Agamémnon, the highest Greek political and military authority, personally shares every soldier's risk on the battlefield and is wounded in action (11:289ff); the King of Lykia, a Trojan ally, is killed in action (15:568ff). Only within the last few centuries has the era of "stone-age command" ended. Before the modern age the ruler and commander in chief were united in one person who was present and at risk in battle. Rear-echelon officers in Vietnam who attempted to micro-manage battles by radio from the rear were known as Base Camp Commandos; those who operated from a helicopter safely out of range of ground fire came to be called Great Leaders in the Sky. Martin van Creveld wrote:

Under the conditions peculiar to the war in Vietnam, major units seldom had more than one of their subordinate outfits engage the enemy at any one time....A hapless company commander engaged in a firefight on the ground was subjected to direct observation by the battalion commander circling above, who was in turn supervised by the brigade commander circling a thousand or so feet higher up, who in his turn was monitored by the division commander in the next highest chopper, who might even be so unlucky as to have his own performance watched by the Field Force (corps) commander.

If American career officers in Vietnam did not share the risks of combat, cultural and institutional factors, rather than personal cowardice, were primarily responsible for this. The officers of World War II had a different culture, which focused on the substance of their work rather than on the institutional definition and status of their jobs, as in Vietnam. And compared to World War II, there were simply too many officers in Vietnam, leading them to become so absorbed in bureaucratic processes that the most elementary aspects of leadership dropped beyond their horizon.

Officers, the only soldiers we meet in the Iliad, went into danger in quest of "honor."

What is the point of being honored so

with precedence at table, choice of meat,

and brimming cups,...

And why have lands been granted you and me...?

So that we two

at times like this in the...front line

may face the blaze of battle and fight well. (12:348ff)

Honor was conferred by others for going into danger and fighting competently. Honor was embodied in its valuable tokens, such as the best portions of meat at feasts, land grants, or, in Achilles' case, the prize of Brisêis. And so could honor be removed; a man could be dis-honored by seizure of the tokens of honor. Homer makes it plain that men were willing to risk their lives for honor and that the material goods that symbolized honor were not per se what made them face "a thousand shapes of death." (12:366) It is easy for us to caricature ancient warriors as simple brigands or booty hunters motivated by greed, but this is almost certainly a misunderstanding. The quest for social honor and avoidance of social shame are the prime motives of Homeric warriors. Achilles says,

Only this bitterness eats at my heart

when one man would deprive and shame his equal,

taking back his prize by abuse of power.

The girl whom the Akhaians chose for me

I won by my own spear. A town with walls

I stormed and sacked for her. Then Agamémnon

stole her back, out of my hands, as though

I were some vagabond held cheap. (16:61ff)

The rage is the same, whether it is fairness, so valued by Americans, or honor, the highest good of Homer's officers, that has been violated. In both cases life is at stake. In both cases the moral constitution of the army, its cultural contract, has been impaired under risk of death and mutilating wounds.

The fiduciary assumption

Compared to the modern soldier, the Homeric soldier hardly depended on others at all, and when he did it was upon comrades he knew personally and called on by name without technology to assist his own voice. He depended upon himself for his weapons and armor; his eyes and ears provided most of the tactical intelligence he required. He did not need to rely on the competence, mental clarity, and sense of responsibility of a chain of people he would never meet to assure that artillery, or air strikes meant to protect him did not kill him by mistake.

Consider the following "routine" event of combat in Vietnam: A man on night watch on the perimeter of a landing zone, using a starlight scope, observes enemy soldiers moving toward the helicopter landing zone (LZ) through the darkness. He calls this in to the command post (CP); his words awaken his comrades, lightly asleep beside him while not on watch. Meanwhile, the officer in the CP calls in a request for illumination shells and artillery fire to turn back or weaken the oncoming assault.

Note the dependency of every man on others: the sleeping men on the one on watch, the one on watch on night-vision equipment supplied by others, all of them upon the radio sets connecting the bunker with the CE They depend upon the radio-telephone operator (RTO) on watch in the CP and the officer who calls in the request for fire support with the correct coordinates and correct munitions, upon the artillery watch officer issuing the correct orders for a fire mission to the nearby fire base, upon these being carried out with the correct munitions and the guns correctly laid -- the wrong coordinates could bring the fire down on the Americans, ironically dubbed "friendly fire," the phrase invoked when the action of one's own arms results in any wounding or death.

The vast and distant military and civilian structure that provides a modern soldier with his orders, arms, ammunition, food, water, information, training, and fire support is ultimately a moral structure, a fiduciary, a trustee holding the life and safety of that soldier. The need for an intact moral world increases with every added coil of a soldier's mortal dependency on others. The vulnerability of the soldier's moral world has vastly increased in three millennia.

The following narrative, which contrasts a respected company commander with his successor, illuminates both obvious and hidden dimensions of the fiduciary relationship:

I told you about that captain I liked, he kept moving us, you know, always move. We'd set up, we'd sleep, if you could sleep, and then get out of there. I think that we walked a lot of unbroken paths, off trails, never set up -- see, my second captain, he'd come up and say, "Well, that's a nice NDP [night defensive position]. It's already dug, little foxholes. It's beautiful, we'll just set up right there." My captain wouldn't do that. He'd shake his head and say, "Uh-UH, we're going over there, and we're going to cut."...Cutting, cutting, cutting...My captain, I hated his goddamn guts, but I admired him, admired the living shit. I hated his goddamn guts because he was so hard....He would always stay off trails, stay off used NDPs. Y'know, when he left and he was replaced, I thought I'd never get out of there. I'd never get out of there alive.

At first glance, this veteran appears simply to be contrasting a competent company commander with his incompetent replacement. The first captain understood that previously used NDPs were probably mined and booby-trapped, or that at the very least, enemy mortars and artillery had their coordinates. Existing trails, which would allow the company to move more quickly without the long labor of cutting through, were likewise mined and booby-trapped as well as invitations to ambush.

Why did the captain who replaced the admired commander not know these things? The answer to this question goes deep into the betrayals of trust of the higher officers who (1) designed a system of officer rotation that rotated officers (above second lieutenant) in and out of combat assignments every six months, (2) were responsible for training, evaluating, and assigning officers to combat command, and (3) placed institutional and career' considerations above the lives of the soldiers under their responsibility. By the time a company or battalion commander acquired knowledge of the enemy's habits, the terrain and weather, the strengths and weaknesses of his men and their arms, whose advice to heed among the junior officers and NCOs, and the arts of deception, he was replaced Some canny commanders would set up in an existing NDP and then move out of it after dark to another position. Such skills are only slightly transferable from one officer to his replacement and mainly have to be acquired from experience.

However, these larger systemic failures such as too-rapid turnover, inadequate training, and incompetent selection of troop commanders misses another important point that was much more visible to soldiers. Was there no one to tell the new captain that he should not use existing trails? Of course there were NCOs and lieutenants to tell him. The old commander, whose way of moving was "cut, cut, cut," probably displeased his superiors who ordered him to move from point A to point B in two hours -- a movement that could be done in that time only if he took his company along highly dangerous existing trails. Possibly he answered back, saying, "No, that can't be done."

Officers who wanted to stay in the field beyond six months were said to have "gone bush" or "gone native." They were suspected of not being "with the program" and of having nurtured a "personality cult" in which the troops were loyal to them as individuals rather than to the chain of command. The veteran quoted above continues,

I had a lieutenant who I loved. I would've walked into hell with him, walked right into hell....Now, when he was supposed to leave the field, he wouldn't leave, they had to bring two armed guards, no lie. They brought a special bird [helicopter] out. They said, "Now get on the bird! You're under orders." He didn't want to go.

Neither the admired captain nor the beloved lieutenant were cowards, avoiding the enemy out of fear. As far as I can determine from this veteran's account, both were effective officers with real loyalty both to their military tasks and to the men under them. They did not place the self-interest of "looking good" to their superiors above the safety of their men. They were not swayed by bureaucratically structured measures of "productivity" derived from industrial processes. The most fundamental incompetence in the Vietnam War was the misapplication of the social and mental model of an industrial process to human warfare.

A full analysis of how war can destroy the social contract binding soldiers to each other, to their commanders, and to the society that raised them as an army deserves a whole book in itself. My purpose here is to draw the reader's attention to the importance in itself of betrayal of thémis, to the soldier's reactions, and to the catastrophic outcomes that often flow from these reactions. I shall do this primarily by focusing on those things that the Iliad brings into view but which long familiarity has made invisible to us.

dLet us look further at the extreme state of dependence of the modern soldier on his army for everything he needs to stay alive in combat: his arms, his training, food and water, communications, knowledge of the enemy, and the skills of his superiors:

My personal weapon until just after this op. [Union I] was the M-14. It was heavy, but at least you could depend on it. Then we got the M-16. It was a piece of shit that never should have gone over there with all the malfunctions....I started hating the fucking government. At least in Union I we had rifles we could depend on. The stocks [of the M-16] broke in hand-to-hand. I started feeling like the government really didn't want us to get back, that there needed to be fewer of us back home. This was a constant thing, they kept changing the spring, the buffer. It was like they was testing it. Our lives depended on them. We cleaned the damned things every day, but they were just no fucking good. There were times when we'd rather use their weapons than our own. I once took an AK [AK-47] from a dead NVA and used it instead of my Mattel toy [M-16].

It was about a week or two into Union II. I was walking point. I seen this NVA soldier at a distance. We were approaching him and he spotted us. We spread out to look for him. I was coming around a stand of grass and heard noise. I couldn't tell who it was, us or him. I stuck my head in the bush and saw this NVA hiding there and told him to come out. He started to move back and I saw he had one of those commando weapons, y'know, with a pistol grip under his thigh, and he brought it up and I was looking straight down the bore. I pulled the trigger on my M-16 and nothing happened.

Obviously this soldier survived the failure of his arms to tell the story, but the experience of betrayal that he took from it has been far more destructive of his subsequent life than the grazing wound inflicted by the NVA. A vast number of military officers, civilian defense officials, and civilian contractors were involved in the specification, design, prototyping, testing, manufacture, field testing, and acceptance of the M-16. Yet as one retired military officer blandly put it, "Early models were plagued by stoppages that caused some units to request reissue of the older M-14." The veteran quoted above experienced the deficiencies of design, manufacture, and especially field testing and acceptance of the M-16 as a gross betrayal of the duties of care and of loyalty by the officers who, by virtue of their office, held his life in trust.

Equipment failure is not new in modern warfare. I count nineteen instances of equipment failure in the Iliad, of which nine were fatal to the soldier in question. Each Homeric soldier, or his father, supplied his own equipment; its failure did not cast doubt on the moral structure of the army in which he served. The ancient soldier was far less dependent in every way on military institutions than his modern counterpart, whose dependency is as complete as that of a small child on his or her family.

During one patrol in the dry season, __'s squad ran out of water and was not resupplied. They walked for a day and a half in search of water in Vietcong-controlled territory. When men started to collapse from dehydration in the heat, an officer's plea for emergency resupply was heeded: A helicopter flew over and "bombed" the squad with cases of Tab, seriously injuring one of the men. The major whose helicopter dropped the Tab was recalled to evacuate the casualty. There was no enemy activity. __ subsequently read in the division newspaper that the major had put himself in for and had received the Bronze Star for resupplying the troops and evacuating the wounded "under fire."

Extreme dependency on others is fundamental to modern combat. We have become so accustomed to this that it easily escapes notice.

Shortages of all sorts -- food, water, ammunition, clothing, shelter from the elements, medical care -- are intrinsic to prolonged combat, if for no other reason than enemy attacks on the army's logistical support services. The fortitude of soldiers under such conditions, for example during the siege of Dien Bien Phu or Khe Sanh, is legendary. However, when deprivation is perceived as the outcome of indifference or disrespect by superiors, it arouses mênis as an unbearable offense.

They had a fucking pet dog at the camp and they always got in fresh hamburger for the dog, but there were times we were out and starving, not even getting C-rations, because they wouldn't resupply us. The dog got sick and they had a chopper in there to fly it to Danang. I had a machete wound in my calf and had to walk for miles back to the base camp.

The shortage that the combat soldier finds most offensive, however, is shortage of competence.

The first deaths in __'s platoon were caused by "friendly fire" from adjoining sectors of the defense perimeter; the officer had neglected to inform them that he was sending men out on the berm....In two successive helicopter-borne combat insertions the company left the landing zone in parallel columns and after a few "klicks" in the jungle lost track of each other until they met in a furious fire fight. Two men were injured in the first one, five in the second. __ never heard of any investigation or disciplinary action.

Another veteran:

There was just one stupid fucking thing after another. They decided to use tear gas on a ville [cluster of hamlets] after we had crossed a river neck deep, and of course everything was soaked, the canisters [of the gas masks] were soaked and they decided to use tear gas. Of course the masks didn't work. They gassed us almost to death.

No one has successfully defined where the inescapable SNAFUs -- a World War II expression: Situation Normal, All Fucked Up -- of war end and culpable incompetence begins.

Is betrayal of "what's right" essential to combat trauma, or is betrayal simply one of many terrible things that happen in war? Aren't terror, shock, horror, and grief at the death of friends trauma enough? No one can conclusively answer these questions today. However, I shall argue what I've come to strongly believe through my work with Vietnam veterans: that moral injury is an essential part of any combat trauma that leads to lifelong psychological injury. Veterans can usually recover from horror, fear, and grief once they return to civilian life, so long as "what's right" has not also been violated.

We now turn our attention to the soldiers' reactions to betrayal of "what's right." These are unchanged across three millennia. Indignant rage will occupy us for the remainder of this chapter. It opens the way for berserk rage, which I will describe in chapter 5.

SOLDIERS' RAGE -- THE BEGINNING

Rage is properly the title of Homer's poem, and his audience may have known it by that name, not Iliad. King Agamémnon causes a ravaging plague in the Greek army by his refusal to accept ransom for the daughter of a priest of Apollo, god of disease and healing. The plague ends only after Achilles mobilizes moral pressure on Agamémnon to return the captive woman. In doing this, Achilles forces him to do what a pious and prudent man would have done of his own accord. Agamémnon, however, takes it as a personal attack by Achilles and seizes Achilles' prize of honor, the captive woman Brisêis, to replace the one he gave up to save the plague-devastated army. Achilles' rage at this wrong is immediate:

...in his shaggy chest this way and that

the passion of his heart ran: should he draw

longsword from hip,...kill

[Agamémnon] in single combat...,

or hold his rage in check...?

...As he slid

the big blade slowly from the sheath, Athêna

...stepping

up behind him, visible to no one

except Akhilleus [Achilles], gripped his

red-gold hair....

The grey-eyed goddess Athena said to him:

"It was to check this killing rage I came

from heaven..."(1:221ff)

Achilles submits and withdraws. His mênis, restrained at the brink of cutting down Agamémnon, is diverted to hacking away emotional bonds and driving away those he used to love. In Vietnam men were not able, as Achilles was, to withdraw physically from combat. They did, however, have the freedom to withdraw emotionally and mentally from everything beyond their small circle of combat-proven comrades.

Homer's starting point, then, is mênis, indignant wrath. I believe it is also the first and possibly the primary trauma that converted subsequent terror, horror, grief, and guilt into lifelong disability for Vietnam veterans. Indignant rage is uncomfortably familiar to all who work with combat veterans.

Homer uses the word mênis for Achilles only in connection with the wrong done to him by Agamémnon, and never in connection with his berserk rage at Hektor for killing his friend Pátroklos. I prefer "indignant rage" as a translation for mênis, because I can hear the word dignity hidden in the word indignant. It is the kind of rage arising from social betrayal that impairs a person's dignity through violation of "what's right." Apart from its use as a word for divine rage, Homer uses mênis only as the word for the rage that ruptures social attachments. We now turn to this choking-off of the social and moral world.

Copyright © 1994 by Jonathan Shay

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (October 1, 1995)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9780684813219

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Clearly one of the most important scholarly works to have emerged from the Vietnam War. Beyond that, it is also an intensely moving work, intensely passionate, reaching back through centuries to touch and heal. —Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried

“A fascinating book that is simultaneously brilliant on Greek classics and the Vietnam War, on modern psychiatry and the archetypes of human struggle. And, on top of that, it says something that is directly meaningful to the way many of us live our lives. Remarkable.” —Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer Prize-winner author of A Good Scent From a Strange Mountain

“A transcendent literary adventure. His compassionate book deserves a place in the lasting literature of the Vietnam War.” —Herbert Mitgang, The New York Times

“Shay's astute analysis of the human psyche and his inventive linking of his patients' symptoms to the actions of the characters in Homer's classic story make this book well worth reading for anyone who would lead troops in both peace and war.” —Thomas E. Neven, Marine Corps Gazette

“Eloquent, disturbing, and original.” —Jon Spayde, The Utne Reader

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Achilles in Vietnam Trade Paperback 9780684813219(0.3 MB)