Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

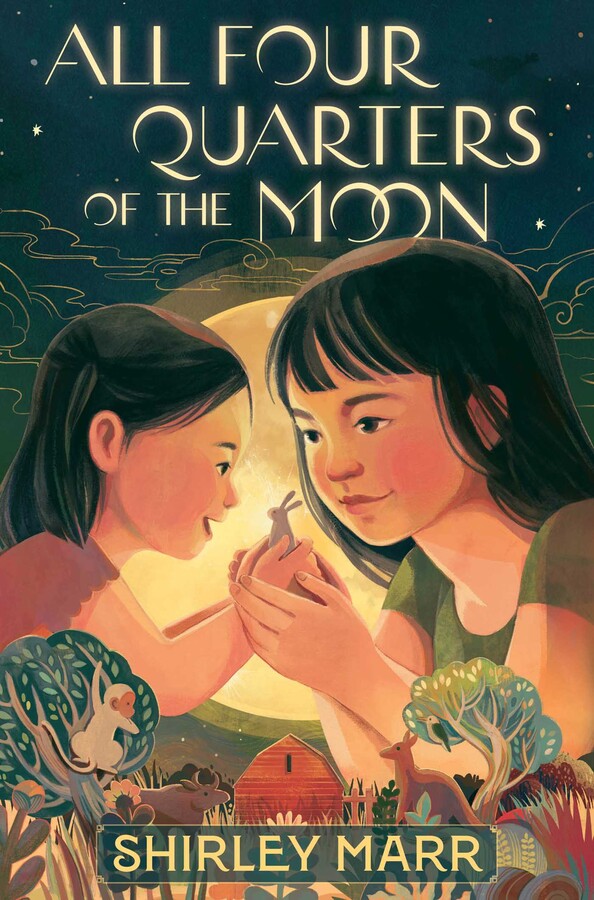

All Four Quarters of the Moon

Table of Contents

About The Book

The night of the Mid-Autumn Festival, making mooncakes with Ah-Ma, was the last time Peijing Guo remembers her life being the same. She is haunted by the magical image of a whole egg yolk suspended in the middle like the full moon. Now adapting to their new life in Australia, Peijing thinks everything is going to turn out okay as long as they all have each other, but cracks are starting to appear in the family.

Five-year-old Biju, lovable but annoying, needs Peijing to be the dependable big sister. Ah-Ma keeps forgetting who she is; Ma Ma is no longer herself and Ba Ba must adjust to a new role as a hands-on dad. Peijing has no idea how she is supposed to cope with the uncertainties of her own world while shouldering the burden of everyone else.

If her family are the four quarters of the mooncake, where does she even fit in?

Excerpt

Ah Ma said she could tell if the mooncakes she was making that year for the Mid-Autumn Festival would be perfect or not just by the feel of the yolk. She had peeled the salted duck egg and weighed it with her hand. It was a good egg. She passed the golden middle to her granddaughter.

“Oh, no,” said Peijing. Eager not to drop it into the sink, she had held on too tight. Now the yolk lay misshapen in her palm, no longer a miniature full moon.

Peijing looked out the kitchen window at the real full moon, hanging so yellow and round that it almost sat on top of all the apartment buildings surrounding their own. She felt as if the moon would drop out of the sky if she so much as breathed wrong.

The Guo family were very superstitious. There were things forbidden during the festival. Don’t point at the moon or the goddess living there will cut your ear. Don’t stare at the moon if you have recently given birth, gotten married, done a bad deal in business, or have too much yang energy in your body.

No one could ever explain properly to Peijing what this yang energy was.

“As the old proverb goes,” replied Ah Ma, “there are no mistakes in life, only lessons.” She smiled mysteriously and passed Peijing another egg yolk.

Ah Ma showed her how to wrap the washed yolks in lotus paste to make the mooncake filling. Peijing let out a breath she didn’t even know she was holding. Ah Ma gently touched her on the shoulder, and she felt like they were sharing a secret.

The Guos were also a very traditional Chinese family who didn’t believe in touching or hugging each other because it wasn’t an honorable thing to hug or touch each other. But sometimes, as Peijing discovered, there were cracks in the rules for those who were very young and very old.

Out through the arched doorway that looked into the living room, where all of Peijing’s aunts and uncles had come to play mahjong, she could hear the shrill voice of Second Aunty saying that she had to leave already. Second Aunty cleaned the airport for a living and had to wake up at five in the morning.

This was followed by the sound of crying. Peijing peered through the doorway, and there was Ma Ma with her face in her hands, looking vibrant in her new green housedress, but sounding as sad as a piece of tinkling jade.

It was definitely forbidden to cry during the Mid-Autumn Festival. Although Peijing was eleven years old now and considered herself far from being a child, she still didn’t understand why adults would tell others not to do a thing and then do it themselves.

But it was no good—Second Aunty still had to wake up at five in the morning. Second Aunty told Ma Ma to stop crying. To think about how Ma Ma and her family were moving to Australia the next day. The move would improve Ma Ma’s yin energy. It would be a lucky life. Not like Second Aunty, waking up at five in the morning, six days a week, to pick up disgusting things travelers left behind on airplanes. They didn’t forget to take just their magazines, you know.

Peijing felt the nerves in her stomach. Block 222, Batu Bulan East Avenue 4, was the only home she had ever known.

She looked out the kitchen window to the playground. It was small and surrounded by the tall apartment blocks on all four sides, and kids would often fight to use the equipment, but Peijing liked how it felt contained and protected against the outside world. Safe. She could see her younger cousins strung out on the climbing frame, lighting up the night with sparklers like a constellation—even though they were definitely not allowed to play with matches. On the highest point of the frame, atop the rocket-ship slide, sat Peijing’s little sister, five-year-old Biju, fearless against the dark.

“Come and help Ah Ma do the next step,” said Ah Ma gently.

Peijing was sure “help” was too generous a word for her grandmother to use, as rolling out the sweet mooncake pastry was the hardest part. She was unsure if she could ever get it as thin as Ah Ma did without making a hole. She declined the rolling pin Ah Ma passed to her.

“How long have you been making mooncakes for?” asked Peijing, surprised that she had never thought to ask before.

“The womenfolk have always been making them as long as I know,” replied Ah Ma. “My mother taught me, and her mother taught her. I can even remember my great-great-grandmother making them. It’s the same family recipe.”

Ah Ma leaned in closer to Peijing. “The secret lies in the homemade golden syrup.”

Peijing marveled at Ah Ma’s long memory. She felt a strange sensation about being the last on a long chain of these mooncake-making women, little Biju showing no interest in mooncakes other than eating them. Peijing felt anxious that she could only do the easy bits, as if time might just run out before she could learn to do it all.

That’s if anyone made mooncakes in Australia anyway.

She had overheard conversations about how different things were going to be for Ba Ba, Ma Ma, Ah Ma, Biju, and her once they arrived. How they would have to learn new ways and new customs. How the stores there might not even sell salted duck eggs.

She wondered what they made for Mid-Autumn Festival in Australia. If they celebrated Mid-Autumn Festival at all.

Ah Ma pressed the pastry and the filling into the wooden molds, and Peijing watched as the mooncakes tumbled out, perfectly shaped and imprinted with mysterious designs on the top.

“What about these designs? What do they mean?” Peijing asked, tracing one of the mooncakes with her finger before hiding her hand behind her back.

“That, I don’t know. These meanings have been lost in time. That symbol is so old that even someone as ancient as me can’t understand it.” Ah Ma chuckled and dabbed the pastry with an egg wash. “It is from before the first written language, when our ancestors used to pass stories from mouth to ear and try to hold them safe inside symbols. Stories would stay for eight thousand years, then stories would fade.”

Peijing had been learning about the universe at school—the big bang, the first stars, the first single- celled life—and she knew, in the scheme of things, eight thousand years was just a blink of an eye. She was worried that this precise moment would disappear and would never come back again.

“But as the old saying goes,” continued Ah Ma, “the palest ink is better than the best memory.”

A written story could last forever. Peijing wasn’t very good at writing her feelings down and she worried about that.

As the mooncakes baked away, Biju suddenly made her grand entrance into the kitchen, plum sauce from the duck she had eaten for mid-autumn dinner still around her mouth, her clothes smelling like firecrackers.

“I want one of those,” she said loudly, peering through the glass into the oven.

She did not say “please.” Manners were also very important to the Guos. As the eldest daughter, Peijing was a mirror, a reflection of her mother. So she was always careful about how she behaved. As her younger sister, Biju was a reflection of Peijing.

Well, supposed to be, anyway. Pejing pressed her lips together and sighed.

“Then you’ve arrived just in time.” Ah Ma smiled. She didn’t mention anything about Biju not saying “please.” She pulled the hot rack out of the oven with a dishcloth.

Peijing looked at all the perfectly baked mooncakes in wonder, and she felt golden and magical. Biju placed her arms around Ah Ma and sank her face into Ah Ma’s apron. Peijing wished she were still small enough to do the same.

“Let’s see how they turned out.” Ah Ma placed one on the cutting board and fetched a knife. Peijing found herself holding her breath again. As if her whole life depended on this moment. Ah Ma sliced down with the knife and pulled the two halves apart.

It was perfectly baked.

The yolk in the middle round and yellow.

Peijing let go and took a breath.

“Yuck!” yelled Biju. “I hate the ones with the stinky egg!”

As abruptly, the thin webbing that held the magic together, where the middle of a mooncake could be as big as the moon, was destroyed. Peijing knew Biju was only five and couldn’t help it, but she wanted to remember this moment as perfect.

Ah Ma divided the mooncake into four pieces. Peijing picked up a slice and looked at the yolk, now a quarter moon, and felt haunted for reasons she could not explain. A cold, empty feeling like the vacuum of space. She popped the piece into her mouth. It tasted delicious. Salty, sweet, and crumbly.

“Don’t worry. I’m going to make your favorite filling next. Sweet red bean with pumpkin seeds,” Ah Ma said to Biju.

“Why didn’t you make my favorite first?” Biju demanded and scrunched up her face. “I might be asleep by the time they finish cooking!”

Peijing sighed again. She always seemed to be sighing at one thing or another, carrying the weight of one responsibility or another on her shoulders. Biju, on the other hand, understood none of these things.

“My apologies. Ah Ma got it the wrong way around. Ah Ma is forgetful these days.”

Biju suddenly went quiet.

“I was really looking forward to eating my last mooncake here,” she said quietly and sucked on her fingers. “We don’t know if anyone even makes mooncakes in Australia.”

And with that, it felt like the universe connected the two sisters again. Peijing’s heart softened.

“Can I help with anything?” Ma Ma appeared in the kitchen, rubbing her face. Peijing did not want to tell her mother that one set of fake lashes on her perfectly made-up eyes was missing. Ma Ma was holding a mahjong tile in her hand. She deposited it absentmindedly on top of the fridge.

Peijing stared up at the symbol for the East Wind.

Ah Ma set Ma Ma to work straightaway rolling pastry. While they were busy chatting, Peijing took her sister by the hand. Together they slipped away, past the adults playing mahjong, to their shared bedroom. Their bare feet moved faster as they approached the door.

To a world of their own.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

All Four Quarters of the Moon

By Shirley Marr

About the Book

What’s it like to move to a new country? Peijing, age eleven, has snakes in her stomach as she boards the plane with her family from familiar Singapore to unknown Australia. Although she was popular back home, Peijing finds at her strange new school that only one girl, Joanna, is friendly. Conscientious and helpful, Peijing tries to protect those around her: Joanna, who has serious problems at home; Biju, Peijing’s younger sister, an exuberant storyteller; and Ah Ma, their beloved grandmother whose memory is slipping. To her surprise, Peijing’s parents are changing in good ways in this new place. Maybe Peijing, too, will finally feel at home, let go of her worries, and pursue her dream to be an artist.

Discussion Questions

1. Why have Peijing and her family moved from Singapore to Australia? Contrast Peijing’s life in the two countries. What things does she miss about Singapore? What does she come to like about her new life in Australia?

2. Describe Peijing’s situation, and her personality. What role does she play in her family? What are some things she likes to do? What matters to her in life? What are her hopes for the future?

3. From the beginning, Peijing mentions snakes: “She kept her feelings to herself, where they multiplied in the pit of her stomach like snakes.” (Chapter four) What are her feelings at this point? When else does she feel the snakes? What do they symbolize for her? Discuss what’s happening here: “She let go of the snakes that had troubled her so and left them in the Serpent Sea.” (Chapter twenty-eight)

4. After Peijing consoles Biju for not getting a bigger part in the play, Biju thanks her. “‘I just want to help,’ replied Peijing, and it was true. That’s all she ever wanted.” (Chapter fifteen) When else does Peijing try to help others? Why is it important to her?

5. In the same scene, Peijing realizes that “In a way she was glad her sister was worried about school plays and spaghetti crowns. Small controllable things. Sweet, simple things.” (Chapter fifteen) What does Peijing herself worry about that seems larger and hard to control? Why do you think she is so prone to worrying?

6. What is Peijing’s relationship with Biju like? Describe Biju’s personality and her skill as a storyteller. How does she adjust to school and other aspects of their new life? How is she different from Peijing? How are they similar?

7. Describe Little World and how it changes. Why was it important to Peijing and Biju to bring Little World with them to Australia? What are the Extinctions? Why is Peijing nervous when Biju shows it to Ba Ba? Explain why he was amazed by it. (Chapter twenty-three)

8. Explain who Ah Ma is and her relationship to Peijing. What is Ah Ma like in the opening scene? Why is she important to Peijing? Give examples of how Ah Ma’s behavior changes. Discuss what Peijing’s parents plan to do about Ah Ma, and how Peijing reacts.

9. How does Ma Ma adjust to the move? What does she miss about Singapore? How do her clothing choices indicate some of her reactions? Why does she decide to apply for a job? Discuss how Ma Ma changes by the end of the novel.

10. What are some of the issues around Ma Ma bringing Peijing’s lunch to school? How does it make Peijing stand out? How does Miss Sara treat Peijing and her mother? Why does Peijing’s mother quit bringing her lunch? When else do chopsticks appear in the story, and in what context?

11. At one point, Peijing observes that she couldn’t remember “the last time she saw Ba Ba smile.” (Chapter eleven) What else did you learn about Ba Ba up to that point? Give some examples of how he changes after that. What prompts the changes? How do Peijing and Biju feel about his new behavior?

12. Why did Peijing purposely fail the test for the special after-school music program? What is the significance to Peijing of Ba Ba and Ma Ma attending Biju’s school performance? Why hadn’t they done the same for Peijing in Singapore?

13. Describe Joanna, then explain how she and Peijing become friends. How do the other students treat Joanna, and why? Why does Joanna worry that Peijing might drop her as a friend? What does Peijing learn about Joanna’s life with her father? Why does Joanna move in with her grandmother, and how does Peijing feel about that?

14. Talk about the magic tree and the role it plays in Peijing’s friendship with Joanna. Why was Peijing surprised that Gem wanted to be invited into the tree? How does the tree help Peijing and Gem become friends? What else helps solidify their friendship?

15. Discuss Peijing’s wish to become an artist. Why is her mother against the idea? What happens with the poster competition? How do you think Peijing feels when Miss Lena calls her a “great artist”? (Chapter twenty-nine) How does she feel when her father says, “‘Drawing is an important skill’”? (Chapter thirty-two) Why does he think so?

16. At the end of chapter sixteen, Ma Ma and Peijing realize that Ah Ma is lost. How has that happened? What is Ma Ma’s reaction? Why is Peijing the one to call the police? Why is Peijing disappointed with her mother? Describe their search and how they find Ah Ma.

17. Discuss Ah Ma’s advice to Peijing:

“You just have to let the feelings guide you. . .You will never be wrong if you are true to yourself. The world—your parents included—will always tell you to be the best version of yourself. I think that is wrong! What we all should be is our favorite versions of ourselves.” (Chapter twenty-one)

18. What does honor mean to Peijing? When she shares her gift for the birthday party with Joanna, and Joanna is grateful, Peijing thinks, “Ma Ma and Ba Ba had thought it was her duty to always behave honorably.” (Chapter twenty) When else does Peijing behave honorably? When does she feel her parents are not doing so?

19. Talk about the book’s title and the titles of the different sections. Why do you think the novel is divided into phases of the moon? What role does the moon play in Peijing’s life and in Biju’s stories?

20. What are some of the threads and themes in the stories that Biju tells? How do the stories relate to the Little World? What are some of the animals in the stories? Who are some of the mythological characters? Choose one story and discuss how it fits into the preceding chapter.

Extension Activities

A Whole New Country

What’s it like to move to a new country like Peijing does? Our communities are filled with people who have moved here from abroad. Ask students to work in pairs to conduct a brief interview with an immigrant, either another child or an adult. Prepare questions as a group, keeping in mind Peijing’s experiences with new customs, language, making friends, and other issues. Ask students to share what they learned with the class. Discuss common themes in the interviews.

Singapore and Australia: Compare and Contrast

Have students do research on Singapore and Australia, using print and digital resources. (An excellent source is CultureGrams, which has a kids’ edition.) Then each student should create a chart with five topics of comparison such as languages, land size, population, government, important historic events, popular culture, education, and so on. Students should share their charts and create a single large chart for the classroom, decorated with photographs.

There’s an Old Saying

Peijing hears several proverbs from Ah Ma during the story. Have students choose among the proverbs in the novel. They should write an essay about what it means, connecting it to the novel. Share interpretations as a class, and discuss other proverbs that students know from their families or experience.

Hunger Close to Home

Miss Sara organizes a fundraiser “for kids starving in an unprecedented famine in another country.” (Chapter thirteen) Miss Sara hasn’t noticed that Joanna doesn’t have enough to eat. Ask students to do research on hunger in the US or in the world, with an emphasis on children. They should find statistics as well as identify organizations and government programs working to eradicate hunger. (Adjust the activity if hunger affects some of your students.)

Women Heroes

When Peijing acts with honor, she feels “as powerful as an ancient warrior like Hua Mulan.” (Chapter twenty) Invite students to find folklore, fairy tales, myths, and legends with strong female protagonists in anthologies or single picture books. Students should choose one of the stories to tell the class, practicing in pairs or small groups before presenting.

Recommended books from the New York Public Library: nypl.org/blog/2021/03/18/heroines-fairytales-folklore-fables-legends

Tips on Storytelling from We Are Storytellers: startwithabook.org/we-are-storytellers-exploring-multicultural-folktales-fairy-tales-and-myths

Guide written by Kathleen Odean, a youth librarian for seventeen years who chaired the 2002 Newbery Award Committee. She now gives all-day workshops on new books for children and teens. She tweets at @kathleenodean.

This guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes. For more Simon & Schuster guides and classroom materials, please visit simonandschuster.net or simonandschuster.net/thebookpantry.

Why We Love It

“Beautiful and emotionally resonant, this touching story about sisterhood, friendship, and family, with a dash of magical realism, will touch any reader who has felt out of place and longed for the safety of home.”

—Krista V., Senior Editor, on All Four Quarters of the Moon

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (July 12, 2022)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781534488861

- Grades: 3 - 7

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 860L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

- Fountas & Pinnell™ W These books have been officially leveled by using the F&P Text Level Gradient™ Leveling System

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

A CBCA Notable Book for 2023

"Fans of sisterhood stories are in for a heartfelt treat with this gentle novel centered around family, resilience, and immigration...[t]aken from the author’s own experiences, the touching characters and relationships in this story will linger with readers for a long time."

– Booklist, starred review

Gentle, observational prose carries the novel’s intentionally paced events, folk tale references, organic character growth, and a heartening message of embracing change and impermanence.

– Publishers Weekly

Peijing’s struggles highlight the nuances of immigration, as she finds her home life and diet to be a frequent source of tension in her new circumstances even as she yearns for the comfort of Chinese traditions and heritage. Interspersed between chapters are Biju’s own retellings of myths and fables, offering the sisters a chance to consider elements of Chinese culture...[t]he book closes on a harmonious note, making this an honest, hopeful choice for anyone experiencing extreme cultural differences and needing some reassurance in their new world.

– BCCB

"Through tales both familiar and new, two sisters navigate growing up and an international relocation....Contrasting Peijing’s anxiety as the eldest child bearing expectations of responsibility, 5-year-old Biju’s exuberant, improvisational storytelling centers the sisters’ interactions as their lives transform in a new and very different environment. While Peijing finds her voice and makes new friends and Biju shines in the school play, Ah Ma’s declining health prompts them to capture memories in the moment. Biju’s retold legends are a highlight, showcasing her irreverent humor and demonstrating a self-assured agency that reminds readers of the power of stories’ evolution."

– Kirkus Reviews

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): All Four Quarters of the Moon Hardcover 9781534488861

- Author Photo (jpg): Shirley Marr Photograph © Isabelle Haubrich(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit