Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

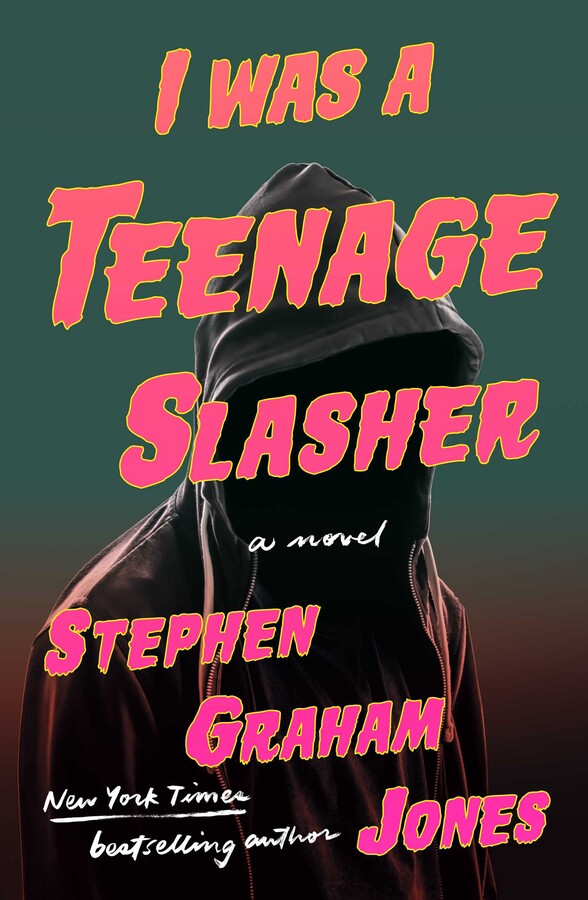

I Was A Teenage Slasher

Table of Contents

About The Book

From New York Times bestselling horror writer Stephen Graham Jones comes a “viciously clever” (The New York Times Book Review) classic slasher story with a twist—perfect for fans of Adam Cesare and Grady Hendrix.

1989, Lamesa, Texas. A small town driven by oil and cotton—and a place where everyone knows everyone else’s business. So it goes for Tolly Driver, a good kid with more potential than application, seventeen, and about to be cursed to kill for revenge. Here Stephen Graham Jones explores the Texas he grew up in, and shared sense of unfairness of being on the outside through the slasher horror Jones loves, but from the perspective of the killer, Tolly, writing his own autobiography. Find yourself rooting for a killer in this “playful, self-aware, and remarkably gory horror novel” (The New York Times).

Appearances

Austin Film Society

B&N Northgate

Excerpt

It was the best of times––high school––and it was the suckiest of times: high school.

Would I trade it, though?

If I could unkill six people, not make the whole town of Lamesa, Texas gnash their teeth and tear their clothes and have to go to funeral after funeral that searing-hot July?

Okay, I’m maybe exaggerating a bit about the clothes tearing. Though I’m sure some grieving brother or friend or conscripted cousin split a seam of their borrowed sports jacket, heaving a coffin up into a hearse. And I bet a dentist or two paid their golf fees with money earned spackling the yellowy molars a whole town of restless sleepers had been grinding in their sleep, not sure if it was over. Not sure if I was gone.

And, yeah––“golf fees”?

I don’t know.

People who wear plaid pants and hit small balls aren’t exactly the crowd I run with.

The crowd I do run with are… well. We’re the ones with black hearts and red hands. Masks and machetes.

And until I was seventeen, I never even knew about us.

My name is Tolly Driver. Which isn’t just this grimy keyboard messing my typing up. Tolly isn’t short for “Tolliver,” and Driver was just my dad’s random last name, and probably his dad before him, and I don’t know where it comes from, and even if I did, even if I had my whole family history back to some fancy-mustached dude reining mules this way and that, it wouldn’t change anything.

In 1989, a thing happened in Lamesa, Texas. No, a thing happened to Lamesa, Texas.

And to me.

And to six people of the graduating class, some of whom I’d known since kindergarten.

It also happened to my best friend, Amber.

She’s why I’m writing this all down at last.

I don’t know where you are anymore, Ambs.

Maybe we weren’t meant to ever see each other again, after we were seventeen?

In real life, I mean. Because I still see you every night, the way you were the summer between our junior and senior years. What was Cinderella’s big song on the radio, then? “Don’t Know What You Got Till It’s Gone”? I should have taken Kix’s advice, though, and not closed my eyes. Not even once.

I know now that we never should have gone to that party at Deek Masterson’s, Amber. What I wouldn’t give to let us just make one more round up and down the drag instead. To have sat on your tailgate at the carwash and watched classmates roll in, pile into different front seats and truck beds, and then leave again. We could have eventually eased out to our big oil tank on the east side of town, done the two-straw thing with our thousandth syrupy Dr Pepper from the Town & Country, and watched the meteors scratch light into the sky then fizzle into lonelier and lonelier sparks, each of us holding our breath, not having to say anything.

When I look back, that’s how I see us best: in the last moments before we turned right on Bryan Street, to slope out to Deek’s on the north side of town, the Richie Rich houses. I’m riding shotgun in your little Rabbit truck, with the bucket seat that slid forward on its rails every time you braked, conking my head on the windshield.

You stopped short a lot that summer.

And me, I laughed until thin blood sheeted down my face. Until it outlined my mouth. Until it was dripping off my chin like I’d been bathing in it.

Don’t look at me like that, please.

That’s not who I really was. That’s just what I ended up doing.

I was a teenage slasher, yeah, okay. I said it.

And it wasn’t because my career placement test told me what I was, and it wasn’t because I’d been harboring secret resentments since sixth grade, about some traumatic prank.

It was because I had, and still live with, a peanut allergy.

How’s that for motivation?

“Tolly Driver’s rage built over the years, seeing his classmates eat trail mix with apparent impunity, until it finally simmered over, resulting in a swath of destruction four days long and six bodies deep.”

That’s the 60 Minutes version of me. If the world had cared enough about Lamesa, Texas to even notice.

Or maybe I’m more 20/ 20 material? “An unassuming high school junior, slight of build, academically unexceptional, recently deprived of his father, woke one morning to see the world through different eyes, worse eyes, more dangerous eyes, and the people around him paid the price.”

That part about the people around me paying the price gets it right anyway, doesn’t it?

Don’t say anything.

I know you paid for being my friend, Amber Big Plume Dennison.

You stood by me when everyone else would have cut me down. You believed in me when I didn’t believe in myself. And then you saved my life.

And now I don’t even know where you are. If you’re happy. If you’re not.

If you also think about that party out at Deek’s.

I do wish we’d never gone.

In some ways, though, I guess I’m sort of still there.

It’s July 14th, 1989, and my forehead’s just bouncing back from the windshield of a seven-year-old Volkswagen pickup.

You’d think that a sudden conk like that might blot out the previous few seconds, since what’s important right after impact is reeling around, dealing with the shock, assessing the damage, trying to decide whether to laugh or cry. Except, first, what I was already saying: this was nothing new for me, that summer. Any brain damage I was to suffer from repetitive whacks to the forehead, I’d probably already suffered it.

Second: in retrospect, I kind of deserved it.

There I was not twenty-four inches from the girl I was too stupid to even consider, and, like the idiot I was, I’d just said another girl’s name: Stace Goodkin.

Not just said-said it, either, like talking about someone I’d seen eat a chili dog in one long bite at the drive-in last weekend. No, I’d sort of intoned Stace’s name, my voice swooning and swanning, my eyes going all unfocused, my head resting back on my neck because I was slack, delirious, smitten.

Okay, I’m overselling it a bit, sure. But it was all in good fun, at least until Amber couldn’t take it anymore, brought me back down to earth by hauling that trusty emergency brake up with her right hand, whipping my head forward into that windshield that hadn’t cracked before, didn’t crack then, and’s still whole and intact nearly eighteen years later, in that Great Junkyard in the Sky foreign cars get retired to.

“Ha, ha, ha,” I drolled out, rubbing between my eyebrows with the heel of my hand, even though the point of impact had been dead center of my forehead.

“She used to babysit you,” Amber said with that kind of incredulity that’s just a shade away from outrage.

She wasn’t wrong.

When I was four and Stace Goodkin was five, she’d evidently been so much more mature and responsible and trustworthy than me that her mom and my mom had agreed that she could look after me for an hour or two, when the two of them needed to be somewhere they could smoke cigarettes and drink coffee without either of their husbands listening in.

Can you fall in love at four years old?

Probably not. Maybe with a dog, or an ice cream cone, or a cartoon.

What I think I did fall in love with, though, at kind of a pre-thinking level, was being Stace’s doll to dress up, to spoon applesauce to, to play Operation with. I’m pretty sure she let me win at hide and seek back then, even.

I would get better with the hiding and the seeking, of course. Like, killer good. And I suppose Operation was a sort of training for me as well, a first look into the endless wonders just under the skin of a human body. And––I should have said this earlier, right up front: this computer doesn’t know italics, so… expect some underlines?

But, Deek’s party.

Deek had graduated two years before, was just home from college––A&M, if that tells you what you need to know––and his parents were in Vegas for the weekend, on their fourth or fifth honeymoon, because they were always breaking up. Mix a pony keg into this situation, and take into consideration that Deek was his parents’ golden boy, could do no wrong, would never get his truck taken away or anything, and: automatic party, right?

“She’s probably not even here, Romeo,” Amber said, twisting the Rabbit’s ignition back. The diesel four-banger clattered and coughed, would take thirty seconds to die all the way down, which was a thing I always respected about it, that it would try to hang on even when it was already a lost cause.

Amber followed up calling me “Romeo” with batting her eyes coquettishly, and the way I got her back for slamming my head into her windshield was to grab the stick shift, tip the transmission up into gear, no clutch, which is a thing you either have to time or be lucky for.

The truck lurched forward a jolt, Amber screeched, and the silver-feather earring she’d had her head tilted over to put in slipped down her palm, vaulted off the heel of her hand, and glimmered down into the floorboard, and the no man’s land under her bucket seat. Unlike on my side, her dad had wrapped some bad-idea tangle of baling wire back and forth from rail to rail, locking her seat at exactly the right place for her but also turning the space under her seat into a rat’s nest of snaggy metal.

“Those are the ones my mom gave me?” Amber shrieked. “That her mom gave her? Are you trying to ruin my whole family, Tol, what?”

“Here,” I said, turning sideways to jam the blade of my fingers under her seat, which was when I noticed the forehead blood on my palm, had to stop to inspect it, follow it up to the red starburst on the backside of the windshield.

“Trying to ruin my family?” I said back quieter, holding my hand higher up into the moonlight.

“Trying to save the world from any more of you, more like,” Amber said with a devious grin, and leaned against the steering wheel to shove her own hand down under the front of her seat, closing her eyes to let her fingers see better.

Ninety careful seconds later, all she came back with was a nick in her index finger.

“Not saying you didn’t deserve that,” I told her, and I’d like to say that the reason we didn’t press our blood together in the cab right then was that, in 1989, we were scared of AIDS, but… okay, I’ll admit it: I’d never even gotten close to first base with anybody but myself. Amber either. Our dance cards weren’t exactly stacked with scratched-out names, I mean, and our bedposts didn’t have any notches in them, were just as virgin as we were. Not saying our blood was necessarily clean––we’d both grown up on well water that left our teeth cotton-field brown, like everybody else’s––but I guess maybe we already felt sort of like brother and sister, no playground ceremonies necessary?

“So now I get lockjaw, great,” she said, sucking her finger.

“That’s your Indian earring, right?” I asked her, never sure how to say it, exactly.

Amber held up the one she still had, said, “My granddad made it?” and the question mark in her tone wasn’t because she wasn’t sure who hammered that silver into a feather all those generations back, it was because, like she was always telling me, anything she had––her backpack, her truck, her basketball––if it was hers, then it was Indian, got it?

“Tomorrow,” I told her. “I’ll dig it out tomorrow.”

“Another Tolly promise?”

“How do you even know you’re going to have a daughter to give those earrings to?”

“Boys can’t wear earrings?”

“Boy George,” I offered, pretty weakly. I only knew him from music videos.

“Yeah, we need more of you,” Amber said, standing.

I stood into the night, breathed its cleanness in.

If you think I don’t miss Texas––well.

The moment we were in, it was… it was like we were standing in the bottom of a giant hollow pin cushion, and somebody had the lights on bright in whatever room we were in. And I guess there were coyotes yapping outside that room’s window, I don’t know. There were around Deek’s house on the north side of town, anyway.

“?‘She’s probably not even here?’?” I quoted back to Amber, about all the cars and trucks parked up and down the road––even one old Farmall tractor. “Everybody’s here, Ambs.”

“DUIs waiting to happen…” Amber muttered, and hip-checked her door shut.

“Not her,” I said back, getting all dreamy and wistful again.

Which Amber couldn’t say anything about, because it was true. No way would Stace Goodkin be one of the inebriated, weaving home. No way would she be riding with someone like that, either. I would say she was one of the good ones, the straight and narrow seniors, but it’s more like she was the only one. She hadn’t ever been seen in the back two rows of the Sky-Vue, or pulled up to Spurlock’s with a beau––as my mom would have said it––and any time Future Farmers of America and Future Homemakers of America took a bus trip together, she always stayed in the hotel room she’d been assigned, running flashcards by herself, politely declining all the guys leaning in her doorway like a movie poster, tipping their heads out to the parking lot, where all the rites of adulthood were waiting.

Those guys were football stars and tractor dealership inheritors and youth group lifers––the kings of Lamesa High––but they never had a chance. Not with Stace Goodkin.

I figured the kid she used to babysit might, though.

You think big thoughts when you’re seventeen.

Big, stupid thoughts.

Don’t let me tell you that Deek’s party had a moment of silence when Tolly Driver and Amber Dennison walked through its batwing doors, either. First, it was just a normal front door, nothing dramatic and Old West about it. Second… and I should say this about myself, not about Amber. No need to pull her down with me. I mean. Any more than I already have.

But, second, I wasn’t that big of a deal yet, I guess you could say? There was no reason for everybody to stop what they were doing, clock my entrance. Everybody knew who I was, of course, but that’s just because we’d all been together since elementary, pretty much. By high school, now, everybody had my number. I was the reason snack time in second grade always involved gummy treats and round crackers and cheese, never almonds or walnuts or peanuts or anything sesame seed–adjacent. “Tolly might have a reaction,” Nurse Lampkin would be there special on day one to say in her hushed voice, somehow making eye contact with every kid in class so they got the life-or-deathness of this.

Translation: Tolly might spasm and foam at the mouth and pee his pants, and then suffocate––and you’d all have to watch, and remember it forever.

I don’t mean to define myself by my allergy, everybody’s got something, plenty have worse, I’m not complaining, but when that’s the first time you become aware of me, I have to figure it’s kind of like the lens you always see me through?

Anyway, I’d been busy trying to shake that “handle with care” thing by always slamming cup after red cup of whatever the spiked punch was at the party, by always jumping off the hayride at its fastest, never caring where or how I landed, and everybody knew it was me who had dragged the sharp teeth of a wide-open stapler––the staples were all bunched up in the mouth––down the wall of lockers on the way to the gym, gouging the metal deeper than the janitor’s paint could fill in.

My big plan to not be so fragile had been working, too. Until my dad, close enough to town to sneak home for a surprise lunch, tried to pass a knifing rig just north of Stanton and met another tractor head-on, which was the joke I wasn’t supposed to know about: he met the John Deere head-on, and it took his head right off.

Now, so far as Lamesa was concerned, I had so many “fragile” stickers on me I was pretty much a mummy. People were “sorry,” “was there anything they could do,” “their uncle died three years ago,” “that road should be wider,” and on and on.

As for Amber, I’d heard the upperclassmen say she “had potential” if she wasn’t so dark, and then maybe take a second look anyway when she passed in the hall, but she was also the girl who’d dipped freshman year, and she was kind of having a hard time living that down. It hadn’t been because she was especially kicker or anything, though. The reason she’d started dipping was to guilt her Army brother into quitting Copenhagen, because she didn’t want him dying from mouth cancer, and it worked, he’s probably out there saving the world right now, but still, as far as high school was concerned, she still had those wet black flecks on her teeth, was still and forever going to be carrying a clawed-open Dr Pepper can around to string muddy lines of spit down into.

We were sort of outcasts together, you could say. On the outside looking in. But? Stand at that tall chain link fence long enough, peering through those metal diamonds, and the hand you have hooked up higher than your head might nudge into someone else’s, and then the two of you can maybe nod, don’t even have to say anything.

I miss you, Ambs.

And I’m so sorry for everything that’s about to happen, here.

What I wouldn’t give to ride in your little joke of a truck just one more time.

These steps we’re taking through Deek’s front door, though, they’re in slow motion, I’m thinking. And they’re so fucking heavy, aren’t they? All of West Texas is shaking each time one of our feet comes down on the tiles of Deek’s entryway. Owls are fluttering down from circle systems, their wings cupping the air. Prairie dogs are looking up to their crumbling ceilings. Porch lights are trembling, dogs are barking, an old grandma is looking at the water her teeth are in, because it’s shaking.

“Shut the damn door!” Lance O’Bryan yelled over the music to us, remember?

At least I think it was Lance. His dad was an auction caller on the weekends, so always brought his loud voice home, or his bullhorn-deafened ears. Either way, Lance could boom it out, was always the one to call plays on the football field, Friday nights.

I swallowed hard, stopped in my tracks, shut that damn door.

“There she is, loverboy,” Amber said to me about fifty times louder than I wanted her to.

She was right: Stace Goodkin was leaned back against the breakfast counter dividing the kitchen from the dining room, and she was earnestly––of course earnestly––listening to some fascinating story Kim Jones was pretty much acting out for her, because words couldn’t contain whatever this was.

“Hey, Stace!” Amber called across the living room, coming up onto her toes and waving, so that not only Stace had to look over, but the whole party did.

“Amber?” Stace said, holding her hand up to put Kim Jones on pause, politely.

“Look who’s here,” Amber said, and did that magician thing where she flourished around, presenting me, in all my skinny awkwardness.

“Tolly Tolly Tolly Driver,” Deek said from the kitchen, and stepped in. “Didn’t even know you knew about this little shindig, hoss.”

Hoss was from the new football coach. All his players and former players were using it, now.

“We can––” I sputtered back to Deek, making to step back out, into my proper place.

“He’s cool,” Stace said though, and after what seemed to me like the longest held breath, Deek shrugged about me, said, “Let the libations flow, then,” and Amber and me stepped down into the party proper, Kim Jones picked her can’t-believe-it story up again, and––

And if the next part’s going to make sense, I need to explain about Deek and his crew, I guess.

And Justin Joss.

I say “Deek,” and he was maybe the ringleader, I suppose, but it was really him and Mandy Lonegan and Trey Meeks and Grandlin Chalmers and Abel Martinez and Abel’s twin sister Ezzy––short for Esmeralda, her grandmother’s name evidently, but using it would get her all up in your face, so: Ezzy.

In their freshman year, when Amber and me had still been in junior high, Deek and them had signed up for the Future Farmers of America’s Leadership team. Not because they were all cuckoo for parliamentary procedure and Robert’s Rules of Order, but because they were freshmen, and if they wanted to go on any of the out of town trips, then they had to compete in the only category the upperclassmen hadn’t already called. Grass judging was already gone and only the seniors got to compete about what to call this or that cut of meat.

That left Leadership. Meaning, if Deek and them wanted to get on that yellow dog and slope out of town, their freshman year was going to be all about seconding this and tabling that. And, because they didn’t have enough Future Farmers to mock up an actual meeting, a couple of the Future Homemakers of America had come across to fill those empty seats: Mandy and Ezzy. It meant their team couldn’t compete-compete, that every meet they went to would officially be just for practice, but it’s not like they were in it to win, either. It was all about a night out of town, with a motel door that opened out onto Lubbock or San Angelo or Abilene or Midland––everywhere’s a big city when you’re Lamesa born and bred.

And then Stace Goodkin came across from FHA as well. While she wouldn’t have been in it to crush the competition, I expect she came at Leadership team the same way she came at her homework, at homecoming committee, at bake sales for the church: all business.

Of course, this freshman for-practice-only team lost their first two meets, which netted them a talking-to from Mr. Thompson, who taught Ag. Their road privileges were threatened, the team might get dissolved until they could take it seriously, all the usual threats.

Deek and crew shrugged, didn’t say anything, couldn’t have cared less, I would guess––in their defense, I wouldn’t have either––but this reprimand cut deep for Stace. It could be the first sort of negative mark on her permanent record, couldn’t it?

She went locker to locker, trying to get everyone to meet after school to run through some mock problems she’d worked up, but it was Friday in late spring, meaning no football game that night, just a track meet in the morning. Nobody showed for her meeting, I mean, and Robert’s Rules of Order are hard to implement solo. You sound kind of like a crazy person, just spewing your made-up problems all over the table.

And, no, no need to say it: Where were you for that crazy-person meeting, Tol?

Truth told, I don’t know. That Friday would go down in town history, kind of become a marker, a cautionary tale, but… maybe I was hanging around the Town & Country, waiting to steal something? Maybe I was throwing rocks at a flock of cowbirds, just to see them rise up so white and flappy? I could have even been hanging out at Amber’s barn, so long as her dad wasn’t around.

Or? If my dad was close enough to Lamesa, he’d swing by school in his work truck, take me with him. He was a pumper. What that meant was he’d go down every caliche road for counties in each direction, to oil tank pads he could find in a sandstorm, and sometimes had to, wearing scuba goggles. Once to that pad, we’d put a hardhat on––company rules, even though there was nothing but blue sky yawning open above us––climb the metal stairs, and unwind a plumb bob down into the tank, then reel it up until the gauge line showed raw crude. After that, Dad would let me crib that measurement into the spiral notebook in the mailbox at the foot of the stairs, so long as I promised to write neat and clear, and then we’d clean the tape and be off to the next one, and the next one, until dark.

Nowadays, I’d guess it’s all automated somehow. Built-in gauges, radio reporting, I don’t know. Back then, it was all about pumpers grinding from tank to tank all the livelong day, and my dad and me singing with the radio between stops, me trying to keep up with the lyrics he’d make up, both of us finally collapsing into laughter.

I know, I know––what if he’d never caught that tractor’s toolbar at sixty miles per hour, right? Do six people in Lamesa, Texas then get a free pass, keep their insides on the inside?

What if, what if.

Maybe it’s better it all worked out like it did, though.

Dad wouldn’t have been proud of what I’m soon to become, I mean. What I guess I still, technically, am.

I don’t have grandchildren for you to spoil, Dad, no. I do have web pages documenting my murder spree, though. That count for anything? What about that TV movie they did, “loosely based on”?

Yeah, it was pretty stupid.

They didn’t even get my mask right.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I was talking about Deek.

Well, really, about Justin Joss.

Justin Joss was a hanger-on. I guess that’s the best way to say it. He was that kind of hopeful-to-be-included that he’d pretty much do anything. Like, on the social ladder? I say that me and Amber would maybe be pretty low. But Justin Joss would be even a rung or two down from us.

Example: in elementary, when there were still glass salt and pepper shakers on the cafeteria tables at school and everybody was always pouring a mound of salt into their hand just to get everybody chanting for them to eat it, eat it, Justin Joss had been so desperate for approval that he’d actually eaten it. He was a year ahead of me, but still, I felt sorry for… for the hopeful way he held his eyes, when he clapped that handful of salt in? What his eyes were asking was, “So, this is good enough? Now I’m in?”

No, Justin.

Sorry.

Though he did get to go home from school early that day. And there would nearly always be crunchy salt underfoot around his locker, which I guess is classmates thinking about you, anyway.

High school’s not the place to try to ever live anything down, no.

Justin Joss deserved better than Lamesa gave him.

But? He probably did save a lot of lives, too. The same way that wrecked Corvette on the flatbed trailer does when it gets parked in front of the school for the lead-up to prom every year.

Anyway, where I’m going with this is that Friday nobody came to Stace’s afterschool Leadership run-through.

I picture her sitting there for the scheduled two hours all the same, running flashcards by herself, and then she’s walking back to her house, her books hugged to her chest like always.

Is she pissed?

Maybe in a Stace-way, which is to say she probably regretted her teammates’ poor decisions, and was concerned about the roads they were unwittingly stepping down, that would lead them, in ten years’ time, to destinations neither they nor their parents ever planned on.

Like I said: Stace cared. She would have babysat all of us, given the chance.

So, she goes home, eats Friday night dinner with her parents, and then, because she’d made the case for a hardship license, she asked if she could maybe have the car keys for a half hour?

It was so she could find her Leadership team, schedule the next meeting.

If Stace Goodkin ever listened to my favorite radio station, KBAT, out of Midland? Then she might have heard “Bang Your Head” at some point. And it might have resonated with her, in trying to deal with Deek and them.

I never found out what she listened to, though. Probably, to make her a safer driver, nothing, right? Or, this night, maybe Robert’s Rules of Order on cassette, which who knows if that’s really a thing.

So, while she was eating dinner with her parents, recounting her week to them, previewing the upcoming one, Deek and crew had spirited Justin Joss out into the cotton fields south of town––“south” because Deek lived north, and you don’t shit where you eat.

What they were doing, they told him––the teachers and parents never heard this, but all the kids did––was inducting him to be part of their gang. Or maybe “initiating”? I guess I don’t even know exactly what the difference is there. But it doesn’t matter.

They piled into Deek’s shiny shortbed with the flashy chrome rollbar, turned all his spotlights on, loaded up on beer, and headed out into the nothing. Which is what you do when you grow up in Lamesa. All kids want to get away, don’t they? Just, in a big city, that means sneaking into clubs, I guess. Or taking a train across town, where you can be anonymous.

In West Texas, nobody’s anonymous, and the only place to go is away from prying eyes. Which means: out into the nothing. Stock tanks you can skinnydip in, if you don’t mind how grody they are. Radio towers you can climb, if you know which ones are hot, which ones aren’t. Junkyards you can sneak into after dark, turnrows you can drink beer in, so long as you don’t leave bottles behind. And… pump roads. The kind my dad knew from biggest artery to smallest capillary, down to which pastures you had to rabbit across, because that’s where this or that rancher keeps his bulls.

And, the thing about pump roads is that they all lead either to oil tanks, like Amber and me liked to climb and lie back on, or pumpjacks. If you don’t know a pumpjack… they’re these monstrous metal dinosaurs with huge counterweights and pretty strong motors to keep them going. Like––there’s windmills that use the wind to push those rods deep into the ground, to get water back up? That’s a pumpjack. Just, without the wind. Pumpjacks aren’t as tall as a windmill, but they’re about three hundred times more solid. A tornado will twist a windmill up, leave it three pastures over. But a pumpjack doesn’t even look over its shoulder if the sky goes green.

Another way to picture a pumpjack: a big metal horse, bucking slow, pulling barrel after barrel of crude up from the ground.

Meaning, yeah, it’s kind of inevitable that kids are going to climb up top, ride it. Especially kids like us, raised on rodeo. Kids who probably rode horses in the parade every year while their granddad was still alive.

That was to be Justin Joss’s rite of passage: ride a pumpjack. Specifically, ignore all the warning signs about loss of limb and life, step over the short metal fence, and find your way up there while someone holds their hand on the power lever, keeping this killer horse still for the moment.

You can guess where this is going, can’t you?

It’s every parent’s nightmare.

And of course very important to Justin Joss’s initiation ceremony here is that he drink beer after beer, for courage. And––according to legend––when he was still too nervous, Ezzy scrambled up there, straddled the pumpjack’s back, then scooched all the way out to the head of the hammer, nodding to Deek to flip the switch. At which point she’s supposed to have gone full-on Debra Winger from Urban Cowboy, which pretty much owned the eighties in West Texas.

How could Justin Joss resist now, right? Even a girl could do it.

Deek slowed the big beast, Ezzy stayed out there, and, awkwardly, hesitantly, looking back over and over probably, Justin Joss ascended, Deek assuring him the whole way, but urging him faster, too.

Right before Justin Joss had his seat, Deek of course turned the power back on, so that the horse’s metal back could rise up, take Justin’s breath away.

Ezzy was already holding on––she was a barrel racer, knew to clamp her thighs––but Justin Joss slid back and forth on that rocking beam, screaming for all he was worth, grasping for any handle, or edge, or bolt.

Deek and Mandy and Trey and Grandlin and Abel held their foaming beers up and toasted the entertainment Justin Joss was providing. Ezzy leaned back, peeled out of her straw hat, and swung it around behind and above her like a steer wrestler, and I imagine this was pretty much the definition of a perfect Friday night for all involved.

At least until headlights swept across the pad the pumpjack was on.

I imagine Deek and the rest of them shielding their eyes and wincing, sure this was one of their dads.

When the caliche dust settled, it was Stace Goodkin.

She’d heard in town where her Leadership team was.

She stood up from the running board, her headlights still on.

“Justin, no!” she was already screaming, running for the pumpjack’s ladder to save him.

And she probably could have.

She was Stace Goodkin, after all.

It was too late, though. What was happening had too much momentum, had been happening since right after school let out, when Mandy sauntered over to Justin Joss, asked if he’d maybe like to hang with them tonight?

Justin Joss looked to Deek, to Ezzy, to Stace, and in that moment of split attention, he slid forward a bit, and tried to grab on tighter like you do, like you would, but… he overbalanced, and fell down into the spinning counterweights. They don’t go all that fast, are pretty much five-ton clock pendulums, but they do definitely go. And they don’t stop, not for hell or high water.

The first one snipped Justin Joss’s right leg off at mid-thigh, and made him sit up enough that the weight on the other side just missed cutting him in half.

He did have to put his left hand back to brace himself, though.

Next rotation, he lost that hand halfway up the forearm.

From the hammer two stories up, Ezzy was screaming for Deek to turn the power off, turn the power off!

Deek did, but those weights still had one revolution to get through. Ponderously, they took a few more inches of Justin Joss’s left arm off, and the only reason Lamesa didn’t lose Stace Goodkin that night was that Abel Martinez, all-district linebacker, did a flying tackle into her midsection.

But as soon as she hit the caliche, Stace was climbing back up, fighting to save Justin Joss, whose various stumps were burbling and gouting slower and slower.

Finally, the big weights came to a stop.

I imagine a bullbat diving down into Stace’s headlights, to snatch a bug up. Or maybe Justin Joss’s soul.

So, that’s Deek and his crew. And that’s Stace Goodkin as well.

And, yeah, by the time me and Amber were freshmen, there was a young tree in front of the high school with a “Justin Joss” plaque on it. If it lived, that tree’s probably throwing some good shade, by now. And the story of a Lamesa high schooler with promise falling into that industrial-sized meatgrinder is what kept so many up-and-comers off the pumpjacks, so: thanks, Justin. You’re part of the gang now, man.

And, to Mr. and Mrs. Joss? I understand why you had to move away to Georgia. Completely. The only eyewitnesses to this tragedy were the perpetrators, right? That’s not whose college exploits and weddings and births you want to read about in the Press-Reporter for the next decade. That’s not who you want to stand in line behind, to pay for your gas.

The funny thing too was that, headed into the living room of Deek’s party, I was already kind of low-key thinking about Justin Joss. Not because I was him in this situation––the wannabe––but because part of me was always still at my dad’s funeral.

Like you do for a town tragedy, everybody had been there for it. A Saturday morning. All the stores closed except the Town & Country and grocery store, pretty much.

I won’t bore you with all the speeches and crying. With all the oilfield workers there in their best clothes. With the feeling in my chest that day. With how Amber stood right there beside me, her hair pulled back and braided down her back, which had to have taken her mom a half hour to get right. Amber even had lipstick on, which doesn’t exactly fit with someone still known for dipping. It wasn’t red, but darker purple, I guess like fits for a funeral. I don’t know if she picked her outfit, if her mom told her what to wear, if they spent the whole night before trying stuff on, what. But I know that when I looked up that day, to her wending her way to me through the headstones, all I wanted to do was walk over to meet her, turn the two of us around, and run and run and keep running.

And Amber, she would have done it, too. I could see it in her eyes. In the hesitant way she was holding her mouth, unsure what exactly her lips looked like, all dark purple.

We would have run until her braid came loose, until my stupid new loafers fell behind us, until the mesquite had scratched our arms and faces so much that our outsides could sort of match our torn-up insides. And she wouldn’t have told anybody how she held my head to her chest when I started crying, couldn’t stop.

But instead, I nodded once to her, she nodded once back, and we walked to my dad’s grave together, made it through the hymns, the handshakes and hugs, and my dad’s coffin, cranking down into that hole in the ground.

After, when everyone was shrugging their way back through the headstones to their trucks, this could also be where all this starts?

It’s like, when historians are trying to go back and say what started World War I? There’s the trigger, I guess you could call it––that archduke getting got––but there’s a lot of precipitating little things as well.

This is one of those little things. And it’s why I associate Justin Joss with my dad’s funeral.

In that mass exodus, all the well-wishers had managed to get my mom and me separated, and Amber’s parents had guided her to their truck, I guess, to get good seats at the reception. But that was fine. I could get to my mom’s truck by myself. And, really, walking alone felt like a good metaphor for all the steps I still had ahead of me in life, now. It’s dramatic, I know, but… this I won’t write off to being seventeen, I don’t think. When your dad dies, whenever in life you are, you realize that you’ve either got to hold yourself up, now, or just start falling and falling.

Anyway, Grandlin Chalmers was ahead of me but going slow. It was because he was walking and trying to open one of those little suckers that had been in the bowl at the church. These are the cheap-o ones like the bank has. Like, their handles or sticks are loops, sort of, that meet in the sucker?

Grandlin got the cellophane off, shook it from his fingers, and the wind took it, sucked it two or three graves over. At which point Grandlin looked back like to see who might have seen this, so he could know if he needed to chase that trash down or not.

“Hey,” I said, just there, grieving.

If it had been anybody else, I don’t think Grandlin would have gone after his litter like he did. I was the special person of the day, though. The grounds Grandlin were trashing up, my dad was part of them now.

Grandlin pivoted, light on his feet as ever, and jogged over for that invisible wrapper.

I watched him not because I was interested, and not because that trash needed to get collected, but because, the whole funeral, I hadn’t known what to do with my eyes. This, watching Grandlin? It was something.

The wrapper had snagged on some dried roses some survivor had left.

Grandlin didn’t even break stride, just reached down to snatch it up. Jogging back to the gravel path, though, he was slinging his right hand, had evidently caught a thorn.

“Every rose,” I may have said or sort of sung in my mouth, under my breath.

It was nice to have something familiar.

Grandlin pursed his lips in a sort of grin, seeing me see him, and then slung his right hand again like it was stinging, and it was only when I walked past where he’d just been that I saw he’d flicked some bright red blood down.

There was a drop on the grass––I don’t know how I zeroed in on it, just believe me that I did––and there were two drops up on the headstone.

Justin Joss’s.

How I knew it was his without even reading the name was that, on the pale granite base of the headstone, leaking dry tendrils of rust down, was a rusty oilfield drillbit Justin’s father had famously hauled out there in a little kid’s wagon, and then left, like an indictment of who and what had taken his only son away from him.

The groundskeeper back then––now too, I figure––would come through and pick up old vases and dead flowers and popped balloons and dried-out wreaths, keep the place from trashing up too much. But nobody had ever touched this drillbit. Probably because we all agreed with Mr. Joss’s indictment. And maybe because it weighed eighty or a hundred pounds: three toothy heads spiraling together to chew down and down, to where the oil is.

I want to ask how could Grandlin have missed where he was flicking his blood––how he could have missed something so out-of-place as that drillbit––but… I’m pretty sure part of being Grandlin Chalmers is being blissfully unaware of the china shop you’re crashing through.

Not so for the Tolly Drivers of the world.

I stopped on the gravel path, watched those two drops of blood until Dick, the assistant manager at my mom’s hardware store, clapped his two-fingered hand on my shoulder and pulled me to him so we could three-leg walk it to the cars, and he didn’t even say anything to me, just held me to his side, and, all these years later, I don’t know if that was the best thing that could have happened after my father’s funeral, or the worst.

I do know that, in my dreamiest of dreams, I imagine clapping my hand onto some fatherless kid’s shoulder like that, and knowing not to say anything.

But my kind don’t exactly go to the funerals, I know.

We’re the reason for the funerals.

Later that week, when I came back to talk to my dad like you do, tell him I was going to do a bottle rocket for him way out farther than anybody else was doing fireworks, I did cruise Justin Joss’s plot, of course.

The blood on the grass was gone like you’d expect, but one of the drops on the headstone was still there.

The week after that, it was gone as well, and the week after that, it was still gone, but that drillbit’s weight had finally sent a crack zig-zagging up through the headstone.

Putting us right about Deek’s party.

Since speaking actual mouth words to Stace Goodkin was turning out to be so much more complicated than I’d imagined––Kim Jones still had her captured, anyway––I was flitting from group to group, and kind of standing around like I was involved in this or that conversation… until I noticed my plastic cup was somehow already empty, leaving me no choice but to retreat to the kitchen yet again, for a refill that was supposed to give me the courage to actually say things to people, instead of just hover and grin like I belonged.

Somewhere in there, Amber asked, “You good?”

She was leaning on the back of the couch, still nursing the same bottle of beer she’d been handed on our trek across the living room. She was having a discussion with Janice Dickerson, one of Lamesa High’s two lookalike baton twirlers, and I admit I was jealous of Amber’s… I don’t know: comfort level? How she didn’t feel weird?

But I was feeling weird enough for both of us.

“Getting better…” I told her, waggling my empty cup and kind of pivoting around her in what was supposed to be a dance move but ended up with me having to catch the floor lamp, which sent shadows smearing all around the living room.

“Party foul…” someone called out in their most bored voice, and I left the lamp rocking, swept away as gracefully as I could, even pulling a deep, gracious bow that I held for two or three long seconds.

Did Stace cock an eye over at her old babysitting charge here?

I don’t know, could only see my shoes. But I think she had to at least clock me a little, didn’t she? Make enough of an ass of yourself, you get noticed, right?

What I really wonder now, though, is if Amber looked over to me acting the fool, then, without skipping a beat, replied to whatever Janice was asking her. Not like she was dismissing me, or pretending not to have walked in with me. More like “Oh, yeah, well. Here’s Tolly being Tolly. In two hours, I’ll be pulling my truck over so he can puke into the ditch, and the next morning he’ll be grandly telling me the legendary tale of this party, and his central role in it, and how his old babysitter was watching his every move, and it’ll be easier for me just to nod and go along with it again.”

That was going to be later, though.

Now was the kitchen.

Since the pony keg was already empty, selections from Deek’s parents’ liquor cabinet were set out on the breakfast bar, along with various mixers: a two-liter of Cherry RC, orange juice from a paper carton, milk in a gallon jug, which seemed like a bad idea waiting to happen, an empty bottle of margarita mix along with one of those blue cartons of salt, and a tube of pineapple juice concentrate that had been broken into from the side, it looked like.

No thank you.

Being an underclassman, I of course couldn’t be picky, had to drink whatever came my way, but still, while RC and milk could taste like a melted coke float––it worked for Laverne, of Laverne & Shirley––I wanted to be throwing up later, not right now.

Trey was standing unsteadily behind the counter of the kitchen, just finishing pouring Cherry RC into what I guessed was rum.

But then he just stared at it there on the fancy countertop.

“Hey, remember?” Deek said then, walking past to the garage, and the way he pinched his thumb and index finger to his lips, it was obvious what they were needing some privacy for.

“For you, kind sir,” Trey said, holding this rum and coke up to me.

It was pretty much the first time I’d had an actual interaction with any of Deek’s crew.

I took the drink, nodded thanks, and… things started getting blurry at the edges. And then in the middle too.

I have a clear memory of throwing up in Deek’s dad’s fancy barbecue grill, and then quietly easing it shut. I remember seeing Amber in the living room and pointing to her like telling my feet where to take me, then smacking almost instantly into the sliding glass door––apparently I was still on the back patio.

When I’d nearly toppled that floor lamp earlier, people had sort of cheered in that way you do when you’re in a restaurant and hear a rack of glasses hit the floor. When I walked into the sliding glass door, though, everybody looked, sure, but then they just turned away like disappointed with me. Or, maybe it was like they were no longer surprised by my antics.

Still? I’d just lost my dad a year ago, hadn’t I? This––me being an idiot––was probably some stage of grief, wasn’t it?

Just let the kid do what he needs to, and be sure to turn his head to the side if he passes out, so we don’t have to bury him as well.

Or, that’s what I tell myself they were thinking, whispering. I pretend like they cared about me and my welfare, yeah. Really, though, I kind of suspect they were somewhere between regretting having let me in and just generally being embarrassed for me. Amber too. But you couldn’t have stopped me, either. Not without kicking me out. I was some version of the preacher’s kid, the sheriff’s kid, who has to make a spectacle of themself to prove they’re not a narc, if that makes sense.

It did to me, back then.

And I’m not even sure anymore if what I was trying to live down was all the pity they had for me, about my dad, or my thing with peanuts. But I was definitely doing this to myself to prove something to them. Just, I can’t say exactly what that was.

Maybe I was more like Justin Joss than I let myself remember, I don’t know. Another kid eating salt in hopes that was the golden ticket to being included, finally.

And then eating more salt, when that first spoonful didn’t work.

Just, sub in “rum and coke” for “salt,” I guess? I went back to the breakfast bar of alcohol again and again, I mean, proudly proclaiming I’d mastered the precise mix of Cherry RC to Captain Morgan’s. Stumbling around, I tried toasting the grandness of the evening by crashing my plastic cup into beers, into other plastic cups, into Amber’s mostly full bottle.

She pulled me aside, said, “Listen, they’re watching you, and not in a good way.”

I turned dramatically from her news flash and cased the living room, trying to see who was watching me in this “not-good” way.

“I’ll just––” I said to Amber, and pointed with my cup hand to the backyard, where, I presumed, there would be less judging going on. In the open air, I wouldn’t have to worry about breaking anything but myself.

On the back patio, I undulated in place by the barbecue, and kept grinning, imagining Deek’s dad opening it up to cook some sausage.

Across the pool, Mel Boanerges, our other baton twirler––who I mistook for Janice Dickerson at first, like always––was sitting on one of those long patio chairs, talking with a cowboy type I couldn’t place. It was summer, though. In summer, all the little communities around West Texas kind of remix, people from Colorado City showing up in Monahans for a couple weeks––grandparents––people from Big Lake working for a week at their aunt’s flower shop in Odessa. This cowboy Mel was talking to could even be someone up from Howard College or down from Tech, right? It was kind of getting to be a problem, really, college dudes hitting the weekend get-togethers, for easy pickings.

Mel and him were drinking from glass tumblers, too, not plastic cups. And the color in those glass tumblers looked like rum and coke to me.

I staggered forward to elucidate them about this wonderful coincidence, us both drinking the same thing on the same night in the same backyard, and thunked my knee immediately into a low planter with a brick edge like a chisel. I still have the scar, even. My last one, I guess. Evidently I yelped––anybody would have––and Mel and this alien cowboy both looked up, then away just as fast.

Standing there trying to swallow my pain, I zeroed in on them across the pool. The cowboy was upping his chin at Mel’s drink, which didn’t need refilling, then curling his fingers into the front pocket of his brushpopper, sliding whatever he got into his own tumbler, which I guess counts as gentlemanly at college? Mel tasted it when he offered––a canteen kiss––then shrugged, giving him permission, it looked like, so he repeated the process with her drink, dribbling something from his pocket into her tumbler.

“Aspirin,” I said to myself, hopefully just in my head.

Supposedly, by 1989 high school science, or just late eighties urban legend, a single aspirin in your coke erased all inhibition. Meaning, a whole handful of aspirin in a rum and coke? There was no telling.

I toasted them from across the way, they didn’t see, and, because somebody’s always got to be first at these kinds of parties, I took a couple running steps to get my spacing down, double- and triple-checked for traitorous brick planters, then launched up and out over the pool, tucking my knees up to my chest so I could really cannonball.

It was glorious.

I mean, in my head? It was glorious. I hung and hung in the air, and everyone turned to track my arc up, up, and then my even slower descent.

When I surfaced, though, it wasn’t all me doing it: Mel’s date––I guess that’s what he was––had me by the hair I’d let grow for summer, was hauling me up onto the tile.

Behind him, shocked, thoroughly splashed, was Mel. She was aghast, had not been expecting a soaking this night.

“No, no!” Deek was saying from somewhere, running in, just stopping Brushpopper’s fist from smacking me in the mouth.

“Why not?” Brushpopper growled.

“Just––just don’t hit him?” Deek said, like a question.

“Yeah, that,” I slurred, and Brushpopper elbowed me in the gut for my contribution, folding me over.

My puke came unbidden, splashed the tile with its chunky brightness, everybody jumping back.

In Brushpopper’s defense, I admit I was being a complete and total ass. And, it wasn’t just Mel who’d been splashed. Brushpoppper’s fancy felt hat was dripping too, I guess. Not that there’s any reason to wear a 10X beaver hat in July, but that’s his hairline receding ten years later, not mine.

Anyway, if you can’t tell, what I’m trying to do here is document each small little step of this night, this party. Just, I have to be careful. I mean, I can try to blame it all on Grandlin at the funeral, for flicking that blood onto Justin Joss’s headstone, I can try to say it was that farmer taking up both lanes on the backside of that slight rise my dad was cresting, I can say it was Brushpopper veering my future one way and not the other, I can even say Trey shouldn’t have given me that first rum and coke, but it starts with me, I know. I’m the archduke, standing up from his car in the parade, and then falling right back down.

“Let me… I’ll just,” I said, dropping to my knees to scoop pool water over my puke.

“No, no!” Deek was still staying, desperately trying to keep me from puke-ifying his pool.

Other hands grabbed me, dragged me onto the grass, away from the pool and its clean water.

“Thanks a lot, Tolly,” Mel said, producing a baton from somewhere on her person, which erased about three of my rum and cokes.

She slapped its white head into her palm once, held it there.

“Sorry?” I managed to say, and then I was being manhandled onto the lounge chair she and Brushpopper had been on.

“I’ll just sit here,” I said, or something like that, and then, behind Mel and Brushpopper, a wall of other forms coalesced, pretty much from nothing.

Well, I say “nothing,” but, they were marching-band members, so… they’d probably been at the party the whole while, but, after the initial shock of seeing someone in their marching-band getup, fresh from summer practice, big ridiculous hat and all, you kind of just erase them from consideration, and go about having your good time.

They were stepping forward now, though. Because I’d splashed one of their own: Mel.

“You’re causing a ruckus again, Tolly,” one of them said.

“We can’t have you ruining another party,” another said.

“Were you even invited?” a third asked.

Get Amber, I wanted to say, but Mel had her baton extended to just a fingerwidth from my nose. Slowly, using it like a hotshot, she guided me to lie back onto the long patio chair.

“I’ll just, I can––” I said, clamping my hands onto the arms to show how this was my new place, I would just stay here, do my time, lesson learned.

“He trustworthy?” Brushpopper asked the marching band.

As one, they all shook their heads no. The tall white feathers on their hats exaggerated it.

I winced, closed my eyes, felt like I was passing a tractor on a farm-to-market road, sure the coming lane was going to be clear.

“I’ll go get something to… you know,” Brushpopper said, swishing his starched-thin Wranglers away, probably to his truck, where he had all manner of reins and latigo to strap me down, keep me and my antics in place.

Mel tracked his exit, then came back to me.

Her eyeliner was smeared and running from pool water, so she looked like an evil clown, a nightmare mime.

“He’s got the right idea,” she said about Brushpopper, and, like being in marching bands gifts you with groupthought or something, all these trumpet blowers and drum bashers and high steppers––never breaking eye contact with me––worked their golden cummerbunds up and removed the wide belts they used to keep their black marching pants up.

“Wait, no, I can––” I tried, but the prisoner’s objections aren’t often taken into consideration.

First they strapped my forearms to the armrests, having to wrap those belts around four or five times, so my arms were completely sleeved up to the elbows.

“Put the buckles on the bottom,” Mel instructed.

Buckles on the bottom of the armrests because I might could use my mouth to undo them if they were on top.

“Now his legs,” she instructed, and they wrapped me to the chair frame at the knees, and then used the last belt around my waist, really cinched it down, then cinched it down even tighter when Mel kneed me in the side.

I wasn’t going anywhere.

“Throw him in now,” one of the marchers said with an evil chuckle, and my adrenaline spiked, but Mel was just watching me.

“Tolly Tolly Tolly,” she was saying, like tsk tsk tsk.

“I’m so sorry––I didn’t mean to…” I was trying to get out, but now she was stepping forward, a knee to either side of my hips. Straddling me, yeah.

My heart skidded to a stop.

“Um,” I managed to get out.

“You’re a big drinker, aren’t you?” she leaned down to whisper into my ear, her right hand reaching out beside her.

What she came back with was Brushpopper’s glass tumbler.

“This one’s on me,” she said, and tilted the lip of the glass to my mouth, tilted it so I either had to drink or let it run down my chin.

I drank.

At this point in the night, I didn’t need even one drop more, but I could still swallow, still gulp.

Maybe it would help me forget, right? Maybe it would blot the whole summer out.

But no––sorry, Ambs.

That would mean losing you as well. And I wouldn’t trade you, or us that summer, for anything. Seriously.

And, please don’t feel bad that you didn’t know what was happening in the backyard. Nobody inside knew, I don’t think, and, since Deek’s parties famously went topless a couple hours after midnight, I know you were positioning yourself far from the pool, so as not to be in any way involved in that.

You and Stace both, right? While all the lookyloo freshmen and sophomores were already stationing themselves in the backyard for the eventual show.

After I’d drained the glass, some of it even coating my chin––I was worried it would make me break out––Mel leaned back to drain the dregs from it as well, taking the ice between her teeth and crunching it so violently.

Baton twirlers, right? They’re made of different stuff than the rest of us.

Behind her, Brushpopper grinned, nodded, then held his hand out for his lady, to get her up off me, spirit her off into the wide-open night. He was carrying a rope, I distantly registered, and was thankful for the belts, because I knew how those ropes felt on skin. Anybody who’d ever been a freshman in Lamesa knew how ropes felt on skin, from getting bulldogged in the high school parking lot while everyone laughed and laughed.

In the moment before Mel was all the way up, though?

Brushpopper’s other hand, his non-Mel hand, was idly fingering into his chest pocket again, like sorting dice, or dimes, or––no, no no no: sunflower seeds?

I wasn’t sure if I was allergic to them or not, had never risked it.

And it didn’t matter.

What he came up with were three or four actual peanuts. Which you can get away with in a Brushpopper from back then––those shirts were waxy, wouldn’t grease up from the salt.

I bucked in my restraints, but, of course, that was what the kid who just got tied down for his own good was supposed to be doing.

Mel grinned, saluted me bye, and her and her marching-band thugs walked away, their feet falling right in step with each other.

Since 1989 in Lamesa, Texas, is gone, never to come back except in accounts like these, I should probably explain it, at least as pertains to peanuts in your coke. Trick was, FFA and FHA and Ag Sciences was cool. The more country you were, the more respect you got, if that tracks. Not for me, all my heroes wore spandex and bandannas, eyeliner and hairspray, but I didn’t really count, either.

For the people who did count, school was a continual game of who can be the most country. So the high school halls were all Wranglers and boots and hats and dip, and the dances in the cafeteria were all two-steps and waltzes, with the occasional cotton-eyed-joe, but you could have expected that. It’s the same in every small town that depends on what tractors can scratch up from the dirt, I imagine. But what you probably couldn’t have guessed would be high schoolers dragging horse trailers to school and parking longways in the parking lot, to show that whoever drove that truck was fresh from the pasture, and going back there right soon, here, after all this inconsequential stuff. And the tighter your Wranglers or Silver Lakes were, the cooler you were. And, after somebody’s dad explained to them that walking heels on boots didn’t nestle into a stirrup so well, then riding heels were all the rage, and all the FFA lifers were suddenly two inches taller, and walking kind of carefully, too, having to balance into Geography, when they were already dizzy and greying out from having to swallow their Copenhagen spit.

It was ridiculous, yeah.

And, yes, I say that as an outsider looking in. But, believe me, I was an outsider who didn’t want in to this fashion show even a little. I was a clown, sure, but I had no intentions of ever being a rodeo clown.

Anyway, part of wearing your membership card on every sleeve you had was using all the songs on 92.3 as a rulebook. No, I didn’t know all the lessons there were to be had on the kicker stations, but even way out of this like I was, there was one song that still made it out to me: Barbara Mandrell’s, about being country when country wasn’t cool. Somewhere in there––I only clearly remember hearing it once lilting across all the cars at the drive-in––there’s a line about how she, Barbara Mandrell, the holdout with unassailable country roots, was putting peanuts in her coke. Seriously. Go look it up, it’s the stupidest thing. But, for all the would-be cowboys and cowgirls, it was a rulebook.

All of which is to say: I should have had my peanut radar up, at least when there were cowboy hats in the area.

But you’re going to slip, too. It’s what my mom was always telling me: no matter how vigilant I was, still, some sneaky peanut was going to find me one day or another. So I had to be ready, didn’t I?

By “ready” I have to assume she didn’t mean drunk, alone, strapped to a patio chair with costume belts from the marching band.

My first thought, after swallowing what I’d just swallowed, was about her, too––Mom. How she was going to have to go sit in those crappy metal folding chairs by a grave again. How Lamesa resident after Lamesa resident was going to be filing into the hardware store for the rest of the year, buying hammers and saws they didn’t need, like putting coins in the offering plate.

My second thought was how it must have felt for Mel, drinking the dregs of that rum and coke––how it must feel to crush soggy peanuts, not ice, between your molars, and then just flit onto the next thing, and the next, not have to be thinking life and death thoughts.

I still wonder what that must be like.

Not that the vending machine here has any peanut snacks in it. I know Lenbo, who stocks it, and he’s good about keeping me alive, says he prefers a world with me in it.

Unlike Lamesa, Texas.

In 1989, in Deek’s backyard, at an otherwise happening party, I was dying.

First to swell––this was almost instant––was my throat. Like my tonsils were balloons. Both sides. I sucked in as much air as I could, knowing full well there was no way it could be enough.

If I’d had my arms, I could have waved, drawn attention, maybe gotten somebody to carve a desperate tracheotomy into me. If I’d had my legs I could have run around, made a spectacle of myself until someone saved my life.

If if if, I know.

It would have been nice to have some of that marching-band telepathy, though. Or even a throat I could have screamed with.

After the throat-swelling came the full-body convulsions––part anaphylaxis, mostly panic.

But, to anyone seeing this?

“Tolly’s bucking against his restraints some more, ha.”

Next it was the… I call it the full-body flush, but I’m not sure what it is, in a medical sense. Maybe lack of oxygen? My organs thinking they’re rats that need to escape a sinking ship? It was my skin heating up, like all the blood was rushing to the surface, getting primed up to seep through my pores.

I was crying, I was suffocating, I was spasming. All Nurse Lampkin’s predictions were coming true: Tolly Driver had ingested The Dreaded Peanut, and now his life could be measured in seconds.

Then, with my throat clenched shut with what I knew was inflammation but felt like two fists pressing on either side of my neck, my body revved up even higher, trying to forcibly eject this vile contaminant I’d let in.

Only, with my throat clenched, throwing up was… complicated.

It came out my nose at first, yeah. Hot and thick like chili, but twice as spicy. When the fists on the side of my throat backed off for a moment, instead of me getting to finally gasp air in, the rest of the puke started spewing out that way as well, some of it even going past my shoes. I was like one of those black and orange fuzzy caterpillars you can step on from back to front, smooshing all their insides out their face, onto some girl you like’s unsuspecting shins.

I fully expected to see my veiny stomach flop out like frogs can do with theirs, when they suck in a poisonous fly. I never have understood how that helps––is having your stomach in your lap somehow better?––but, bucking and dying on that chair, I one hundred percent got the necessity of having that bad stuff on the outside instead of the inside.

Never mind that this wasn’t the first time I’d thrown up that night. All I was supposed to have in me at this point was rum and coke. But these spasms were digging deeper, into my intestines. Which is to say, yes, after the chunky stuff and the thin stuff, all coating my shirt and pants, came some more sludgy stuff, that I had to think had been compacted for its long muscular grind through my plumbing.

It was caking up through my throat now, though, more and more of it, breaking up as it came through, my body more desperate not to die a peanut death than it was concerned with ever letting me draw a breath again.

All I could move, strapped down like this, was my head, too. It could have been enough, except my neck was locked in puke convulsions, which only wanted my chin lower, lower, maybe to keep me from aspirating all this back in.

And, I suppose there was a peanut or two in all that mess, coated in bile and nearly-through-me refried beans and a kernel of corn I had no memory of and some heat-lamped shredded brisket that John-o, the clerk at Town & Country, had said he stayed away from personally, as he preferred his food to look different going in than coming out.

A grand total of maybe two peanuts, swimming in all that?

I don’t doubt that they were evil enough that wings unfolded from their salty backs, so they could lift heavily from the muck, look around in their dim way for the next allergic reaction, for the next family to wreck.

What I’m saying is I was dying, strapped to that chair. And not a single person at that party was clocking it. No one except for––God bless her––Stace Goodkin.

Through the plate glass window of the dining room of the house, I could see her, still captured by Kim Jones’s novel of a story she just had to keep on telling. Which must have been boring enough that Stace’s eyes took a moment to case her surroundings, skate from face to face, window to window, make sure no one was being taken advantage of, that no one was getting alcohol poisoning, that no family portraits were being vandalized.

When she saw what was happening to me, her mouth opened by degrees, and… I guess the best way to say it is that she became my babysitter again. The one my mom and dad had sat down and lectured about what to do if cute little Tolly somehow ingested a peanut.

Instead of running to me like any other person would probably have done, Stace turned, vaulted over the dining table––she’d been taking gymnastic lessons at some place in Lubbock since kindergarten––and… she ran away?

Later I would find out that, once she saw what was happening, she knew exactly what I needed, and so beelined the one person who might know where it was: Amber.

Amber would tell me that Stace grabbed her by both shoulders, stared lasers into her skull, and asked where my EpiPen was. According to Amber––and this must have been so glorious to hear, but it’s the only way Stace could have gotten across the desperation of this moment––she even asked where my fucking EpiPen was, and shook Amber hard enough that her head slung back and forth, that her bottle of beer fell to the carpet, foamed up through the neck.

Which quieted the party right down.

“Glove compartment?” Amber would tell me she got out, and that’s all Stace needed. She was already running outside, for Amber’s distinctive little truck. As far as we knew, in the land of big trucks––West Texas––Amber’s was the only VW pickup there was, and when you might be going to have to run from cops busting the party up, you don’t slow yourself down by locking your doors.

But, all the way in the backyard, I didn’t know what Stace was doing, of course.

And I wasn’t bucking so much anymore, either.

It was kind of nice.

I’d come into glancing contact with peanuts before––it’s part of having this allergy––but my mom or dad had always been around to jab me safe before it got this far, and then race me to whatever doctor or nurse there was, hold my shivering self to their chests for the whole ride, whispering things down to me I could never remember.

I was on the other side of that now, though. Of “life,” I mean.

And, from my new vantage point? No breath in me, my eyes blurry with tears, my skin going cold now?

I saw Death skulking behind the back fence.

It was rotting, its head a skull trailing wisps of hair, its face covered with a… with a white mask?

No, no, of course: with a popped balloon. From the cemetery. There were always balloons left out there, bobbing from headstones.

Death had snagged one of them, ripped a couple of eyeholes, and somehow got it to stick to its face.

It didn’t matter.

Death’s death, right?

I was kind of calm about it, I guess.

And things were becoming clearer now. My oxygenless brain knew with a clarity I’d never known before that an angel had come to my dad last year, told him I was going to die at seventeen, and given my dad a choice: go on without me, tend my grave, tell stories about me to anyone he could corner, or… or drive into that tractor on purpose, and be there waiting for me, so I wouldn’t be alone in the afterlife. So I wouldn’t be scared.

It’s the kind of thing he would have done, I mean.

Thanks, Dad.

Of all my memories, this is one I treasure, the one I’ll never let go of.

Okay, okay then, I said to Death, coming around to the gate.

But then it stopped in its tracks, seeing something itself.

I turned to track where it was looking, and there was Stace Goodkin, one hand planted on the wide top of Deek’s six-foot cinderblock fence, her feet tucked together beside her, my big plastic EpiPen from Amber’s glove compartment clamped between her teeth, her hair floating gloriously all around her.

You only get a few posters in your life, I’m pretty sure.

This is one of mine.

I tried to open my mouth, I’m not sure why, but my throat was still too swelled or clogged up to even creak a sound out.

And now Stace was running hell for leather across the backyard, launching up over the pool, which I knew was disaster, since no human could make it all the way across, not even her, but––of course: she hit the diving board with her right foot, let it take her weight and shoot her up and up, the rest of the way across to me.

She didn’t even worry about landing, either. If you want to know what a hero is––what Amber would call a “final girl”––then it’s this, I think. It’s Stace coming down from the sky, plucking that EpiPen from her mouth on the way, and landing on the tile around the pool on her knees, damn the consequences.

She slid to me hard enough that the lounge chair lurched back, its rear feet clawing into the grass, tilting me up, and then her left hand, stronger than I would have ever guessed, was jamming that EpiPen into the side of my thigh and holding it there so my dying body could suck it dry.

My vision tunneled down to a point, to just one star up there in the West Texas sky, and then that blotted out too, and it was quiet inside myself at last. Quiet and calm.

I was riding in Amber’s little truck, my arm out the window.

I was climbing the metal stairs of a great oil tank with my dad, walking up to the sun.

My mom was calling down the hall of our house on a Saturday, asking where I was.

I’m here, I croaked back, and Amber looked over to me from the driver’s seat, my dad looked up to me from the numbers I’d just written down perfectly in that little spiral, and my mom smiled at me like she could see all the versions of me waiting to happen, all the versions she knew she could never tell me about, since that would ruin the surprise.

And then my eyeball froze solid.

I lifted my hand to swipe this pain away, and some part of my head registered that my arm wasn’t tied down anymore.

It was Amber, rubbing my face with an ice cube.

I sat up as far as I could, and––the party was over? Which tracked: if somebody’s dying in the backyard, then that means the cops are going to be here soon, and nobody wants a minor-in-possession. Or to be associated with a classmate’s death.

There’d been a mass exodus when word percolated through the house that Tolly Driver had finally done it, was finally and for real killing himself.

It was for the best they were all gone, though.

I was still wet all over, but the pool water was cold. Unlike my crotch. Not from Stace touching me, not from the body-temperature Tolly-salsa heaved up from my stomach, but from my bladder having let go.

The less witnesses to that, the better.

That’s what I was thinking about, yeah. Nobody wants to be the kid who peed their pants.

And, I say the party was over, and it was, but that didn’t mean everyone was gone, either. Standing in a clump over on the patio were Deek and Ezzy and Grandlin and Abel and Trey and Mandy.

And in the kitchen, the phone’s cord spiraling to her, was Stace. Now it was her hands that were alive with explanation.

Did I mention that her dad was a doctor? He was, maybe still is. The good-of-heart probably just get to live and live, don’t they?

“Tol, Tol, you there?” Amber was saying to me.

I tried to muster a response, couldn’t exactly make words yet. But she could see where I was looking: Deek and crew.

“Oh, them,” Amber said, turning her back to them so what she said could just be for me. “They’ve got experience with covering this kind of stuff up, don’t they?”

I nodded, got it: they were getting their story straight, probably for when Dr. Goodkin showed up, Sheriff Burke in tow. The EpiPen had saved my life for the moment, yeah, but EpiPens don’t get you all the way out of the woods, can cause their own set of problems.

“I can’t lose you, Tol,” Amber said then, her eyes brimming over, both her hands holding my right one, and all I could do was purse my lips tight, angle my head to try to redirect the tear tumbling down my face, like doing that could hide it.

Amber lowered her head so she could pretend not to have seen me crying.

Some people are just good, aren’t they?

I wonder what that must be like.

The next time I looked up, Ezzy was standing over me, Deek and the rest behind her, their eyes penitent and hopeful. I realized from all their postures––watching without watching, waiting without waiting––that Ezzy had been elected the speaker, here, even though it was Deek’s house. Probably because she’d worked the nursery at church since forever, so had that soft talking-to-kids thing down.

That’s what I was to them: an idiot kid. One who hadn’t even been invited. One who could ruin this whole summer for them.

“Are you okay, Tolly?” Ezzy asked so softly, with so much manufactured care.

Amber rolled her eyes, had to look away, say, “He’s––”

“We’re asking him?” Deek clarified from across the pool.

“What’s with his face?” Grandlin said, doing his fingers over his own to show what he meant, about mine.

“Shut the fuck up?” Amber said across to him.

“It’s just capillaries,” I managed to creak out, doing my fingers at my face like Grandlin had. They burst when you do the kind of puking that’s supposed to save your life.

“Eww…” Mandy Lonegan said, holding the side of her hand over her mouth and taking a step back.

“Like we don’t all hear you throwing up in the last stall after lunch?” Amber said across the pool. “But you’ve got make-up to cover your burst capillaries up, don’t you?”

Mandy guffawed like affronted about this baldfaced lie, then took a challenging step forward, into this, Amber standing as well, accepting this challenge, her hands balling into fists by her legs, and Trey and Deek did that cat-hiss girl-fight thing, dancing away in that stupid thrilled way.

“It just capillaries,” I said again, quieter and kind of halfway checked out, the congealed puke on my chin and around my mouth heavy and cracking. Not really meaning to then, just moving, adjusting, not wanting to be in this moment anymore, I pulled my arms up and… and they actually came up? The wide belt that had been holding my right arm started to slide away, and I lurched to the side after it, like keeping it from hitting the ground could keep the marching band from being even more pissed at me.

“You?” I said up to Amber, about the loosened belts.

“They never should have done it,” she said back, her lips still thin, eyes still flaring.

I reached farther to the side for the belt that had hit the ground and realized that the belt at my waist was still buckled, keeping me there.