Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

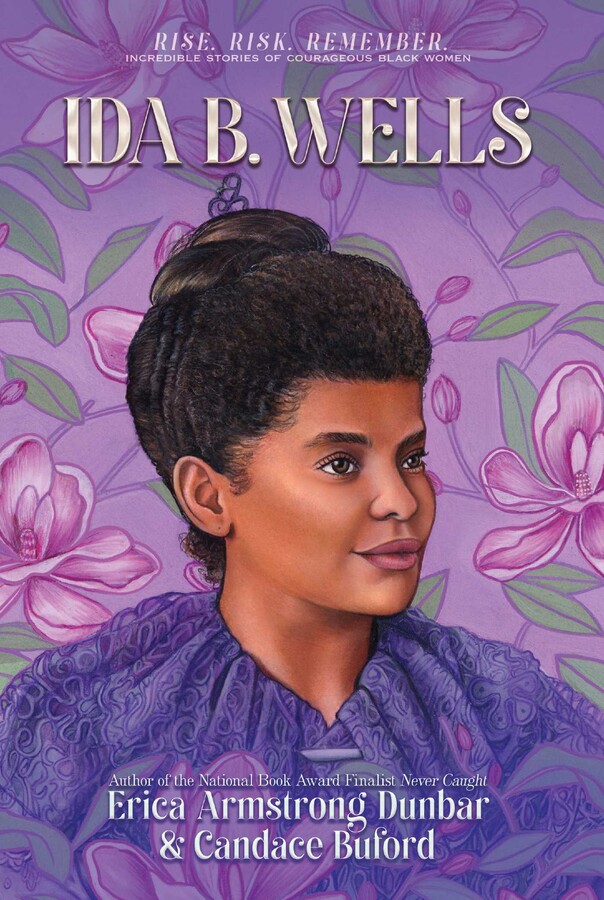

Ida B. Wells

Journalist, Advocate & Crusader for Justice

Table of Contents

About The Book

Meet journalist and activist Ida B. Wells in this second vibrant middle grade biography in the Rise. Risk. Remember. Incredible Stories series spotlighting Black women who left their mark on history from acclaimed and New York Times bestselling author Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Candace Buford.

Born into slavery, Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) grew up watching her family fight for Black rights during the Reconstruction Era. After receiving her education, Ida worked as an educator before moving to Memphis where she began writing about white mob violence, investigating lynchings and reporting her findings in local newspapers. Ida helped found the NAACP and was a renowned leader in the civil rights movement, but she was also a young woman desperately trying to hold her family together after tragedy with dignity and resolve.

Ida fought to give voice to the people suffering from injustice, racism, and violence. She spoke out against lynchings internationally and refused to cater to the white women leading the suffrage movement. Throughout her life, she devoted her words and deeds to activism.

Born into slavery, Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) grew up watching her family fight for Black rights during the Reconstruction Era. After receiving her education, Ida worked as an educator before moving to Memphis where she began writing about white mob violence, investigating lynchings and reporting her findings in local newspapers. Ida helped found the NAACP and was a renowned leader in the civil rights movement, but she was also a young woman desperately trying to hold her family together after tragedy with dignity and resolve.

Ida fought to give voice to the people suffering from injustice, racism, and violence. She spoke out against lynchings internationally and refused to cater to the white women leading the suffrage movement. Throughout her life, she devoted her words and deeds to activism.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 Chapter 1

WHEN MY FATHER CAME HOME from work, he smelled of sandpaper and sawdust, of earthy notes mixed with wood stains and sweat. His carpenter’s hands were calloused but not as rough as some of the other men.

He had started working for his enslaver, who was also his father. When he was old enough, he was brought here, to Holly Springs, Mississippi, to apprentice his carpenter trade. When the war ended, my father snatched his freedom.

One of the beautiful moments from my father’s time in Marshall County, Mississippi, was meeting my mother. He married her while they were both still enslaved. And then married her again when they both had their freedom.

By the way his eyes twinkled when he looked at her, I figured he’d marry her over and over again.

He opened his arms and wrapped them around Mama.

“Come here and let me give you a squeeze.”

“Oh hush.” Mama blushed, swatting him away. By the way she clamped down on her lips, though, I could tell she was amused. She turned back to her cooking, pots bubbling on the stove, and said over her shoulder, “Supper isn’t ready yet, but will be soon.”

“That’s all right. I walked back with some of the other Masons to discuss the news. We’ll sit outside for a while yet.”

“Can I come too?” I asked. “Please? I finished all my schoolwork. Please?”

“Listen to that child!” My mother chuckled by the stove. She looked over at me. “Just as persistent as the day she was born.”

Mama said I popped into the world with urgency, which seemed right. As much as I enjoyed attending school, I loved listening to my father talk politics with the leading men of our community. The sun was setting on my childhood—at sixteen years old, I was on the cusp of womanhood. And I had as much interest in America’s Reconstruction as any man. This was a time of rapid change, a reintegration of the Confederate states into the Union and an establishing of equal rights for emancipated Black people.

I folded my arms, waiting for permission.

“Oh, all right, fine.” Mama sighed and then turned back to her bubbling pot.

I followed closely behind my father as he walked to the porch. My sister Eugenia, who was sitting next to the fireplace, shrugged her shoulders at me. I returned her indifference with an eye roll. She didn’t understand why I bothered with politics instead of choosing to play with my friends. In fact, none of my siblings showed much interest in the news of the day. But I found it all very fascinating and important. I was almost an adult, and I felt an urgency that things were changing. I just wasn’t sure they were changing for the better.

But I wanted to be at the center of it all.

My father reclined in his chair on the porch, surrounded by some of his friends, many of whom were also involved in the community. They were tired from working all day but still wanted to gather to talk about the things that were changing. The chapter of Radical Reconstruction, which had ushered in a whole bunch of Black politicians, congressmen, and even two senators across the South, promised hope and optimism in the days following the Civil War. With slavery ended, these Republican statesmen tried to construct laws that would protect the rights of formerly enslaved people and Black people across the country. But the rift between Democrats and Republicans remained as wide as the Mississippi River, and the new legal protections for Black Americans were already being chipped away. It was 1878 and only thirteen years had passed since the end of the Civil War, but it felt like things were moving backward. I could see the worry on my father’s face as he shifted in his chair. I sat on the porch near his feet, ready to hang on his every word.

“Why don’t you read tonight, Ida,” he said as he unfurled his newspaper from his breast pocket and handed it to me.

“Yes, sir.” I reached for the paper. I couldn’t help the smile that tugged at my lips. Children weren’t usually permitted to be part of adult conversations, especially female children. But I happily jumped at the chance.

So I sat on my perch in front of these men and read the news of the day to my father and his friends. Although they were all skilled tradesmen and community leaders, some of them did not know how to read. Their weary spirits seemed revived as I confidently read out loud. My father’s eyes were alert. He was enlivened. His friends leaned forward, nodding me on in encouragement, maybe even admiration.

But flipping the page to read the next headline, I stumbled over the words. I took a breath and read on.

INNOCENT BLOOD SHED

The two events of the past fortnight, which the Recording angel of God put down to the debt of this country, were the lynching of a colored woman in Virginia, charged with inciting a boy to burn a barn, and the hanging of two colored men in Delaware believed by nine out of every ten to be innocent.

I paused, letting the words sink in. Three people had been lynched—murdered without a trial. I shifted uncomfortably, thinking about how frightened I was. There were laws meant to protect people from being condemned without a trial. But those laws did not seem to extend to Black people, not even innocent ones.

“Let me see that,” my father mumbled under his breath as he slid the paper from my hands. His eyes scanned the page and he tightened his lips in a scowl. He glanced at the surrounding men. “It was probably the Klan.”

I’d heard the name of this group before. Whoever they were, this KKK group had all the men looking tense. I heard my mother and father talk about them and knew they were the reason for the anxious way my mother walked the floor at night when my father was out at a political meeting. Yet as far as I knew, the Klan hadn’t burned down anything in Holly Springs.

The floorboards creaked behind the front door, and I could tell that my mother was inside pacing now. She worried when my father was out at political meetings, but when he managed to have them here, she was doubly nervous there would be some retribution.

“They aren’t claiming responsibility.” My father rolled his eyes with a tight smile.

“They didn’t say they didn’t do it neither,” said a younger gentleman named Timothy from his seat on the porch railing.

“So the Klan is stirring up trouble again. How long you think we have until they come to Holly Springs, Jim?” The man looked at my father, his wide eyes filled with fear.

“These men will come here?” I gulped, grabbing my father’s leg.

“It’s okay.” My father grazed my cheek with the backs of his fingers. His face was tight with worry, but he looked into my eyes. He didn’t fool me, but I found comfort in his efforts. He shook his head slightly and said, softly, “I won’t let them get anywhere near you.”

The front door swung open and my mother appeared, her anxious eyebrows upturned. She was slightly flushed, probably from all the pacing she was doing.

“Come here, child.” My mother snapped her fingers at me. She pursed her lips in a tight line and cocked her head to the side, waiting. “Well, come on then.”

“Listen to your mama,” my father said as he nodded his head. When he turned to look at my mother’s arched eyebrows, he sighed, his shoulders deflating. “She has to learn the truth somehow.”

“I don’t want the Klan mentioned in this house,” my mother said. She stomped her foot on the threshold, emphasizing her claim on her own front door. “They’re already in the streets. I won’t have them casting shadows on this house and giving my babies nightmares.”

“But—” I started to say that I wanted to hear more about it. My father was right: I had to learn the truth. But my mother raised a menacing eyebrow, one that meant for me to do as I was told. My time on the porch had come to a swift and decisive end.

“Why don’t you all get washed up for supper,” my grandmother said, leaning around my mother in the doorway. She didn’t live here. But when she spoke, my daddy listened.

“All right, Mama, we’re finishing up here in a moment’s time.”

As the door shut behind me, I could hear the conversation continue, a little quieter than before, with hushed whispers of politics that my father didn’t want us to overhear. Of course, I had already overheard things around town on my way to school. My parents couldn’t shield me from the world forever.

When I came inside, I was met with the boisterous noise that often filled our house. We were a large brood, the Wells family. I had three younger sisters and three younger brothers, and we were never short of liveliness. Eugenia, Annie, Lily, James, George, baby Stanley, and I kept my parents busy.

Eugenia, who was the closest in age to me, sat in her chair near the fire. Her legs, which had stopped working when she was younger, were covered in a blanket. She waved me over to join her.

“I was supposed to wash up for dinner and help Mother,” I said, eyeing the long kitchen table where my brothers were fighting over a wooden toy and my sisters were engaged in a fit of laughter.

“I think there’s enough going on there,” Genie, the nickname I called Eugenia, said as she smiled mischievously and slid a book from underneath her blanket. She passed it to me. “I just finished reading this. It’s good.”

“Oh, Little Women!” My fingers grazed over the hardcover, itching to crack it open and begin reading. But Mama plucked the book away from me before I could even read the title page.

“Come on, girls. You know you’re only supposed to read the Bible on Sundays.”

“But I’ve already read the Bible through once. Plus, Father let me read from the newspaper tonight,” I whined. I looked longingly at the book that was now firmly locked in my mother’s grasp. She raised an eyebrow, a challenge for me to keep mouthing off to her. I sighed and said, “Yes, ma’am.”

“Here you go.” Eugenia reached under her chair and quickly produced a Bible.

“What else you got under there?” I asked, smirking as I studied her armchair. She broke out into a toothy grin and I joined her. My sister, who was limited in her mobility, was always ahead of everyone with her mischievous nature.

“I’ll put this in your bag,” Mother said as she walked over to my suitcase. “You can read it on your trip to Grandma’s house.”

“Mama, I already have enough books to finish my homework.”

“Good. You can read any chance you get.” She looked over her shoulder as the bag flapped shut. “Your job isn’t just learning in school. It’s taking every opportunity to enrich your mind. Understood?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Just then my nostrils puckered up at the smell coming from the stove. “Are those pork chops?”

“And buttermilk biscuits.” Mama wagged her head from side to side, evidently pleased with herself. “Mr. Boling has been trying to get my recipe for years. Had to politely let him down again today. It was my mama’s secret, and it’s all I have left of her.”

She shrugged and turned back to the stove, hiding her unshed tears. After the war, Mama had tried to find her family in Virginia, but she never saw them again. She and her two sisters were sold as slaves, but fortunately they all lived in Mississippi, not too far from one another. My mother loved her sisters. This was made clear when my mother gave me the middle name Bell in honor of her sister Belle. For my mother, her husband, children, and sisters were her top priority.

“What’s the secret to the biscuits?” I asked, leaning toward the kitchen to get another whiff of them.

“If I didn’t give it up for my employer, what makes you think I’d tell you?” my mother asked playfully. She laughed when I shrugged sheepishly. “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

Mama was known far and wide for her cooking, and she still worked for Mr. Boling.

“I suspect Boling is still mad that Jim didn’t stay on and work with him after he was apprenticed,” Grandma said. “When my son makes up his mind, there’s no turning him around.”

“He would have gladly stayed on,” my mother said. “But after he refused to vote Democrat the way the old man wanted him to, Jim turned up and the shop was locked. Jim had to go find work for himself.”

“I suppose it was for the best.” Grandma waved her hand dismissively. She sank into the kitchen chair with a sigh and turned to me with a smile. “All your friends are so excited to see you when you come to Tippah County with me.” Then she looked over at the window, listening to my father’s muffled voice on the porch, almost like she was making sure he wasn’t within earshot. “And Miss Polly would probably love to see you once you get settled in.”

“Miss Polly?” My mother’s ice-cold voice came from the edge of the stove. Her eyes narrowed to slits. “You taking my daughter to the plantation?”

I looked from mother to my grandmother, shrinking back to the wall so that I wouldn’t be in the cross fire. Mama was shooting daggers with her stern scowl. The front door creaked open, drawing everyone’s attention to that side of the house, where my father was stepping over the threshold.

“All right, y’all. I’ll see you around tomorrow.” He waved goodbye to his friends and closed the door behind him. When he looked to the rest of us, he frowned at the silent stiffness emanating from the kitchen. “Uh-oh. What’d I step in?”

“Your mother,” my mother said, whipping her dishcloth over her shoulder then planting her hands on her hips. “Your mother wants to take our daughter to see Miss Polly when she’s over in Tippah County. To the old man’s plantation house.”

“Oh.” My father nodded and stepped carefully toward my mother. His smile slowly melted into a scowl that mirrored my mother’s.

I didn’t remember being in bondage. Born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in the summer of 1862, I was emancipated before I could scarcely walk. But my parents remembered it. The scars of enslavement were much deeper in their memories, though they tried to put it behind them.

My grandmother, who still lived near the old plantation, was still steeped in that old world. She cleared her throat, speaking softly. “As you know, I’ve been taking care of Miss Polly in her old age. I talk about you and the children most every day.” She hesitated, chewing on the inside of her cheek. “She’d love to see you too—if you just come home for a few days, I’m sure I can have it all arranged.”

“No, Mother. Not this again.”

“I just think…” Grandmother started, but my father cut her off.

“I know you’ve forgiven her. I don’t know how you’ve forgiven her—only by God’s good grace, I suppose. But I haven’t.” My father’s frown hardened when he spoke about Miss Polly. Miss Polly was married to his biological father. They had been the enslavers of the plantation. He turned away from my grandmother so that she wouldn’t feel the full brunt of his ire. “I’ll never forget how she had you whipped. When the old man died, she had them rip your dress so that you could feel the lash on your skin. I’ll never forget that.”

Grandma bowed her head, her fingers fidgeting in her lap. “She is sorry for it.”

“Oh, she apologized for it?” My father raised a skeptical eyebrow.

“Well, no. But she’s shown it in her own way. And now all she wants is companionship. And given that she and her husband never had any children of their own, she is eager to see you, to know how you’re faring.”

“I think I can safely speak for my wife and me on this. We do not want our daughter—or any of our children—to ever step foot in that house.”

“Agreed.” Mama nodded definitively, jutting her chin out. “We don’t want anything to do with that woman. I’ve felt the whip many times. Enough times to know that a slaver’s heart is hardened. And I don’t want to expose my children to that. My Ida may have been born enslaved, but the rest of her life will be lived beyond the gates of any plantation.”

“My thoughts exactly,” said my father as he straightened his collar and pulled out the kitchen chair at the head of the table. He slumped into his seat, looking weary as he gazed at his mother. “Maybe we should postpone Ida’s trip. Just to make sure we understand each other.”

“I understand,” I said from my silent corner of the room.

Three pairs of eyes turned to focus on me, as if they were surprised to see me there. Children were supposed to be seen but not heard. It was brazen of me to insert myself into grown folks’ business. I was still only sixteen—not old enough for a seat at a table or to run my own household. I treaded carefully in this space. “I promise not to go to the plantation.”

I clasped my hands as if in prayer, willing my parents to allow me to go. I hadn’t been to Grandma’s house in ages, and as my grandmother had said, I had some friends there who I wanted to see. And I did like to travel. Tippah County, Mississippi, was only about fifty miles away. I loved to watch the fields change. I loved passing through small towns, looking at all the people I didn’t know, wondering what stories they had to tell. I found it all very fascinating.

“All right then, Miss Ida.” My father chuckled under his breath. He looked at me for a moment, taking me in. “Seems like you’ve found your voice. Don’t ever lose it.”

“I won’t.” I shook my head, making my pigtails swish across the back of my dress. “Promise.”

“And when you get back,” my mother said as she gripped my shoulders, bending down to whisper in my ear, “I’ll tell you the secret to those biscuits.”

And then she kissed me on top of my head.

WHEN MY FATHER CAME HOME from work, he smelled of sandpaper and sawdust, of earthy notes mixed with wood stains and sweat. His carpenter’s hands were calloused but not as rough as some of the other men.

He had started working for his enslaver, who was also his father. When he was old enough, he was brought here, to Holly Springs, Mississippi, to apprentice his carpenter trade. When the war ended, my father snatched his freedom.

One of the beautiful moments from my father’s time in Marshall County, Mississippi, was meeting my mother. He married her while they were both still enslaved. And then married her again when they both had their freedom.

By the way his eyes twinkled when he looked at her, I figured he’d marry her over and over again.

He opened his arms and wrapped them around Mama.

“Come here and let me give you a squeeze.”

“Oh hush.” Mama blushed, swatting him away. By the way she clamped down on her lips, though, I could tell she was amused. She turned back to her cooking, pots bubbling on the stove, and said over her shoulder, “Supper isn’t ready yet, but will be soon.”

“That’s all right. I walked back with some of the other Masons to discuss the news. We’ll sit outside for a while yet.”

“Can I come too?” I asked. “Please? I finished all my schoolwork. Please?”

“Listen to that child!” My mother chuckled by the stove. She looked over at me. “Just as persistent as the day she was born.”

Mama said I popped into the world with urgency, which seemed right. As much as I enjoyed attending school, I loved listening to my father talk politics with the leading men of our community. The sun was setting on my childhood—at sixteen years old, I was on the cusp of womanhood. And I had as much interest in America’s Reconstruction as any man. This was a time of rapid change, a reintegration of the Confederate states into the Union and an establishing of equal rights for emancipated Black people.

I folded my arms, waiting for permission.

“Oh, all right, fine.” Mama sighed and then turned back to her bubbling pot.

I followed closely behind my father as he walked to the porch. My sister Eugenia, who was sitting next to the fireplace, shrugged her shoulders at me. I returned her indifference with an eye roll. She didn’t understand why I bothered with politics instead of choosing to play with my friends. In fact, none of my siblings showed much interest in the news of the day. But I found it all very fascinating and important. I was almost an adult, and I felt an urgency that things were changing. I just wasn’t sure they were changing for the better.

But I wanted to be at the center of it all.

My father reclined in his chair on the porch, surrounded by some of his friends, many of whom were also involved in the community. They were tired from working all day but still wanted to gather to talk about the things that were changing. The chapter of Radical Reconstruction, which had ushered in a whole bunch of Black politicians, congressmen, and even two senators across the South, promised hope and optimism in the days following the Civil War. With slavery ended, these Republican statesmen tried to construct laws that would protect the rights of formerly enslaved people and Black people across the country. But the rift between Democrats and Republicans remained as wide as the Mississippi River, and the new legal protections for Black Americans were already being chipped away. It was 1878 and only thirteen years had passed since the end of the Civil War, but it felt like things were moving backward. I could see the worry on my father’s face as he shifted in his chair. I sat on the porch near his feet, ready to hang on his every word.

“Why don’t you read tonight, Ida,” he said as he unfurled his newspaper from his breast pocket and handed it to me.

“Yes, sir.” I reached for the paper. I couldn’t help the smile that tugged at my lips. Children weren’t usually permitted to be part of adult conversations, especially female children. But I happily jumped at the chance.

So I sat on my perch in front of these men and read the news of the day to my father and his friends. Although they were all skilled tradesmen and community leaders, some of them did not know how to read. Their weary spirits seemed revived as I confidently read out loud. My father’s eyes were alert. He was enlivened. His friends leaned forward, nodding me on in encouragement, maybe even admiration.

But flipping the page to read the next headline, I stumbled over the words. I took a breath and read on.

INNOCENT BLOOD SHED

The two events of the past fortnight, which the Recording angel of God put down to the debt of this country, were the lynching of a colored woman in Virginia, charged with inciting a boy to burn a barn, and the hanging of two colored men in Delaware believed by nine out of every ten to be innocent.

I paused, letting the words sink in. Three people had been lynched—murdered without a trial. I shifted uncomfortably, thinking about how frightened I was. There were laws meant to protect people from being condemned without a trial. But those laws did not seem to extend to Black people, not even innocent ones.

“Let me see that,” my father mumbled under his breath as he slid the paper from my hands. His eyes scanned the page and he tightened his lips in a scowl. He glanced at the surrounding men. “It was probably the Klan.”

I’d heard the name of this group before. Whoever they were, this KKK group had all the men looking tense. I heard my mother and father talk about them and knew they were the reason for the anxious way my mother walked the floor at night when my father was out at a political meeting. Yet as far as I knew, the Klan hadn’t burned down anything in Holly Springs.

The floorboards creaked behind the front door, and I could tell that my mother was inside pacing now. She worried when my father was out at political meetings, but when he managed to have them here, she was doubly nervous there would be some retribution.

“They aren’t claiming responsibility.” My father rolled his eyes with a tight smile.

“They didn’t say they didn’t do it neither,” said a younger gentleman named Timothy from his seat on the porch railing.

“So the Klan is stirring up trouble again. How long you think we have until they come to Holly Springs, Jim?” The man looked at my father, his wide eyes filled with fear.

“These men will come here?” I gulped, grabbing my father’s leg.

“It’s okay.” My father grazed my cheek with the backs of his fingers. His face was tight with worry, but he looked into my eyes. He didn’t fool me, but I found comfort in his efforts. He shook his head slightly and said, softly, “I won’t let them get anywhere near you.”

The front door swung open and my mother appeared, her anxious eyebrows upturned. She was slightly flushed, probably from all the pacing she was doing.

“Come here, child.” My mother snapped her fingers at me. She pursed her lips in a tight line and cocked her head to the side, waiting. “Well, come on then.”

“Listen to your mama,” my father said as he nodded his head. When he turned to look at my mother’s arched eyebrows, he sighed, his shoulders deflating. “She has to learn the truth somehow.”

“I don’t want the Klan mentioned in this house,” my mother said. She stomped her foot on the threshold, emphasizing her claim on her own front door. “They’re already in the streets. I won’t have them casting shadows on this house and giving my babies nightmares.”

“But—” I started to say that I wanted to hear more about it. My father was right: I had to learn the truth. But my mother raised a menacing eyebrow, one that meant for me to do as I was told. My time on the porch had come to a swift and decisive end.

“Why don’t you all get washed up for supper,” my grandmother said, leaning around my mother in the doorway. She didn’t live here. But when she spoke, my daddy listened.

“All right, Mama, we’re finishing up here in a moment’s time.”

As the door shut behind me, I could hear the conversation continue, a little quieter than before, with hushed whispers of politics that my father didn’t want us to overhear. Of course, I had already overheard things around town on my way to school. My parents couldn’t shield me from the world forever.

When I came inside, I was met with the boisterous noise that often filled our house. We were a large brood, the Wells family. I had three younger sisters and three younger brothers, and we were never short of liveliness. Eugenia, Annie, Lily, James, George, baby Stanley, and I kept my parents busy.

Eugenia, who was the closest in age to me, sat in her chair near the fire. Her legs, which had stopped working when she was younger, were covered in a blanket. She waved me over to join her.

“I was supposed to wash up for dinner and help Mother,” I said, eyeing the long kitchen table where my brothers were fighting over a wooden toy and my sisters were engaged in a fit of laughter.

“I think there’s enough going on there,” Genie, the nickname I called Eugenia, said as she smiled mischievously and slid a book from underneath her blanket. She passed it to me. “I just finished reading this. It’s good.”

“Oh, Little Women!” My fingers grazed over the hardcover, itching to crack it open and begin reading. But Mama plucked the book away from me before I could even read the title page.

“Come on, girls. You know you’re only supposed to read the Bible on Sundays.”

“But I’ve already read the Bible through once. Plus, Father let me read from the newspaper tonight,” I whined. I looked longingly at the book that was now firmly locked in my mother’s grasp. She raised an eyebrow, a challenge for me to keep mouthing off to her. I sighed and said, “Yes, ma’am.”

“Here you go.” Eugenia reached under her chair and quickly produced a Bible.

“What else you got under there?” I asked, smirking as I studied her armchair. She broke out into a toothy grin and I joined her. My sister, who was limited in her mobility, was always ahead of everyone with her mischievous nature.

“I’ll put this in your bag,” Mother said as she walked over to my suitcase. “You can read it on your trip to Grandma’s house.”

“Mama, I already have enough books to finish my homework.”

“Good. You can read any chance you get.” She looked over her shoulder as the bag flapped shut. “Your job isn’t just learning in school. It’s taking every opportunity to enrich your mind. Understood?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Just then my nostrils puckered up at the smell coming from the stove. “Are those pork chops?”

“And buttermilk biscuits.” Mama wagged her head from side to side, evidently pleased with herself. “Mr. Boling has been trying to get my recipe for years. Had to politely let him down again today. It was my mama’s secret, and it’s all I have left of her.”

She shrugged and turned back to the stove, hiding her unshed tears. After the war, Mama had tried to find her family in Virginia, but she never saw them again. She and her two sisters were sold as slaves, but fortunately they all lived in Mississippi, not too far from one another. My mother loved her sisters. This was made clear when my mother gave me the middle name Bell in honor of her sister Belle. For my mother, her husband, children, and sisters were her top priority.

“What’s the secret to the biscuits?” I asked, leaning toward the kitchen to get another whiff of them.

“If I didn’t give it up for my employer, what makes you think I’d tell you?” my mother asked playfully. She laughed when I shrugged sheepishly. “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

Mama was known far and wide for her cooking, and she still worked for Mr. Boling.

“I suspect Boling is still mad that Jim didn’t stay on and work with him after he was apprenticed,” Grandma said. “When my son makes up his mind, there’s no turning him around.”

“He would have gladly stayed on,” my mother said. “But after he refused to vote Democrat the way the old man wanted him to, Jim turned up and the shop was locked. Jim had to go find work for himself.”

“I suppose it was for the best.” Grandma waved her hand dismissively. She sank into the kitchen chair with a sigh and turned to me with a smile. “All your friends are so excited to see you when you come to Tippah County with me.” Then she looked over at the window, listening to my father’s muffled voice on the porch, almost like she was making sure he wasn’t within earshot. “And Miss Polly would probably love to see you once you get settled in.”

“Miss Polly?” My mother’s ice-cold voice came from the edge of the stove. Her eyes narrowed to slits. “You taking my daughter to the plantation?”

I looked from mother to my grandmother, shrinking back to the wall so that I wouldn’t be in the cross fire. Mama was shooting daggers with her stern scowl. The front door creaked open, drawing everyone’s attention to that side of the house, where my father was stepping over the threshold.

“All right, y’all. I’ll see you around tomorrow.” He waved goodbye to his friends and closed the door behind him. When he looked to the rest of us, he frowned at the silent stiffness emanating from the kitchen. “Uh-oh. What’d I step in?”

“Your mother,” my mother said, whipping her dishcloth over her shoulder then planting her hands on her hips. “Your mother wants to take our daughter to see Miss Polly when she’s over in Tippah County. To the old man’s plantation house.”

“Oh.” My father nodded and stepped carefully toward my mother. His smile slowly melted into a scowl that mirrored my mother’s.

I didn’t remember being in bondage. Born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in the summer of 1862, I was emancipated before I could scarcely walk. But my parents remembered it. The scars of enslavement were much deeper in their memories, though they tried to put it behind them.

My grandmother, who still lived near the old plantation, was still steeped in that old world. She cleared her throat, speaking softly. “As you know, I’ve been taking care of Miss Polly in her old age. I talk about you and the children most every day.” She hesitated, chewing on the inside of her cheek. “She’d love to see you too—if you just come home for a few days, I’m sure I can have it all arranged.”

“No, Mother. Not this again.”

“I just think…” Grandmother started, but my father cut her off.

“I know you’ve forgiven her. I don’t know how you’ve forgiven her—only by God’s good grace, I suppose. But I haven’t.” My father’s frown hardened when he spoke about Miss Polly. Miss Polly was married to his biological father. They had been the enslavers of the plantation. He turned away from my grandmother so that she wouldn’t feel the full brunt of his ire. “I’ll never forget how she had you whipped. When the old man died, she had them rip your dress so that you could feel the lash on your skin. I’ll never forget that.”

Grandma bowed her head, her fingers fidgeting in her lap. “She is sorry for it.”

“Oh, she apologized for it?” My father raised a skeptical eyebrow.

“Well, no. But she’s shown it in her own way. And now all she wants is companionship. And given that she and her husband never had any children of their own, she is eager to see you, to know how you’re faring.”

“I think I can safely speak for my wife and me on this. We do not want our daughter—or any of our children—to ever step foot in that house.”

“Agreed.” Mama nodded definitively, jutting her chin out. “We don’t want anything to do with that woman. I’ve felt the whip many times. Enough times to know that a slaver’s heart is hardened. And I don’t want to expose my children to that. My Ida may have been born enslaved, but the rest of her life will be lived beyond the gates of any plantation.”

“My thoughts exactly,” said my father as he straightened his collar and pulled out the kitchen chair at the head of the table. He slumped into his seat, looking weary as he gazed at his mother. “Maybe we should postpone Ida’s trip. Just to make sure we understand each other.”

“I understand,” I said from my silent corner of the room.

Three pairs of eyes turned to focus on me, as if they were surprised to see me there. Children were supposed to be seen but not heard. It was brazen of me to insert myself into grown folks’ business. I was still only sixteen—not old enough for a seat at a table or to run my own household. I treaded carefully in this space. “I promise not to go to the plantation.”

I clasped my hands as if in prayer, willing my parents to allow me to go. I hadn’t been to Grandma’s house in ages, and as my grandmother had said, I had some friends there who I wanted to see. And I did like to travel. Tippah County, Mississippi, was only about fifty miles away. I loved to watch the fields change. I loved passing through small towns, looking at all the people I didn’t know, wondering what stories they had to tell. I found it all very fascinating.

“All right then, Miss Ida.” My father chuckled under his breath. He looked at me for a moment, taking me in. “Seems like you’ve found your voice. Don’t ever lose it.”

“I won’t.” I shook my head, making my pigtails swish across the back of my dress. “Promise.”

“And when you get back,” my mother said as she gripped my shoulders, bending down to whisper in my ear, “I’ll tell you the secret to those biscuits.”

And then she kissed me on top of my head.

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (June 3, 2025)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781665919821

- Grades: 5 and up

- Ages: 10 - 99

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Ida B. Wells Trade Paperback 9781665919821

- Author Photo (jpg): Erica Armstrong Dunbar Photograph by Whitney Thomas(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): Candace Buford Clementine Cayrol(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit