Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

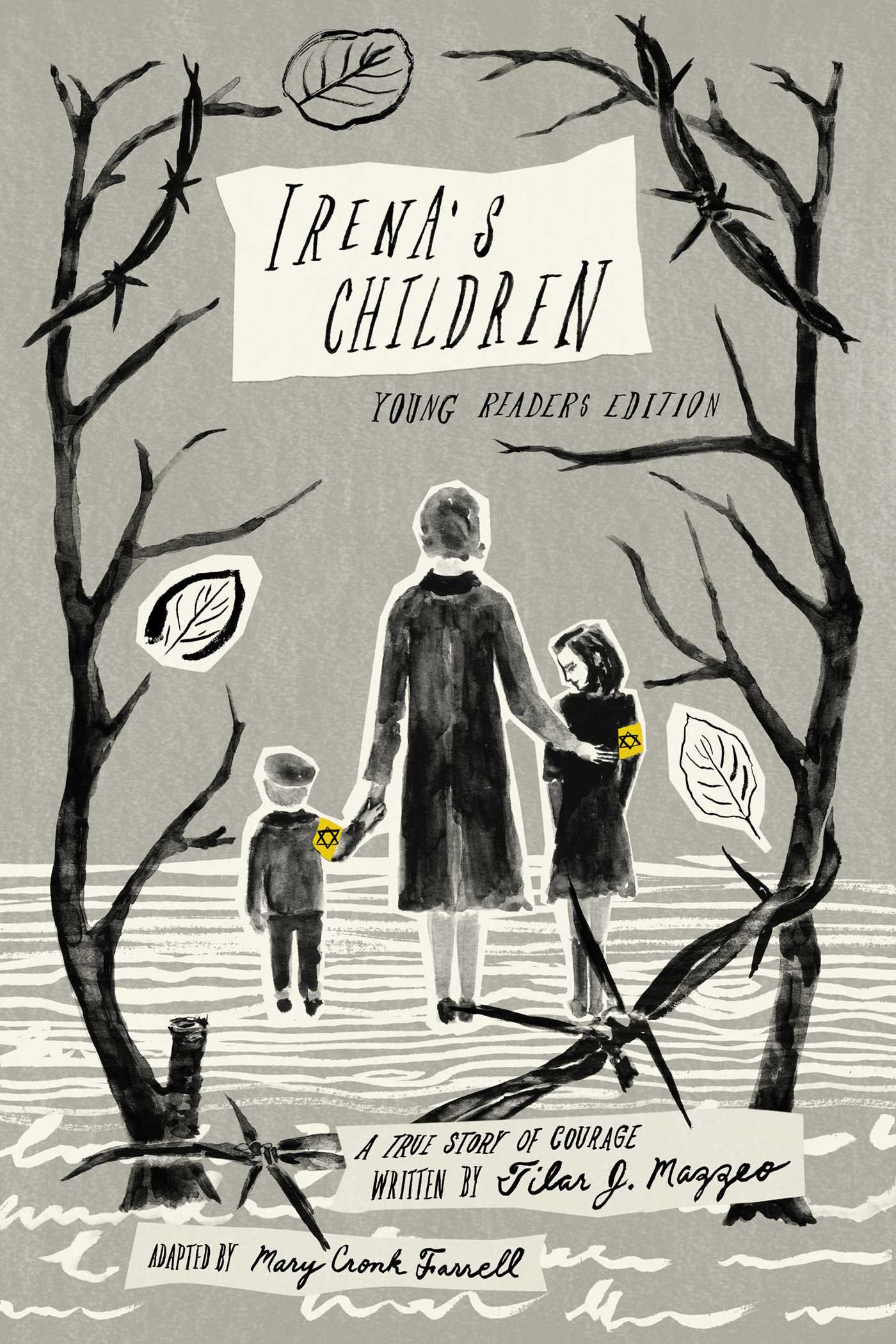

From New York Times bestselling author Tilar Mazzeo comes the extraordinary and long forgotten story of Irena Sendler—the “female Oskar Schindler”—who took staggering risks to save 2,500 children from death and deportation in Nazi-occupied Poland during World War II—now adapted for a younger audience.

Irena Sendler was a young Polish woman living in Warsaw during World War II with an incredible story of survival and selflessness. And she’s been long forgotten by history.

Until now.

This young readers edition of Irena’s Children tells Irena’s unbelievable story set during one of the worst times in modern history. With guts of steel and unfaltering bravery, Irena smuggled thousands of children out of the walled Jewish ghetto in toolboxes and coffins, snuck them under overcoats at checkpoints, and slipped them through the dank sewers and into secret passages that led to abandoned buildings, where she convinced her friends and underground resistance network to hide them.

In this heroic tale of survival and resilience in the face of impossible odds, Tilar Mazzeo and adapter Mary Cronk Farrell share the true story of this bold and brave woman, overlooked by history, who risked her life to save innocent children from the horrors of the Holocaust.

Irena Sendler was a young Polish woman living in Warsaw during World War II with an incredible story of survival and selflessness. And she’s been long forgotten by history.

Until now.

This young readers edition of Irena’s Children tells Irena’s unbelievable story set during one of the worst times in modern history. With guts of steel and unfaltering bravery, Irena smuggled thousands of children out of the walled Jewish ghetto in toolboxes and coffins, snuck them under overcoats at checkpoints, and slipped them through the dank sewers and into secret passages that led to abandoned buildings, where she convinced her friends and underground resistance network to hide them.

In this heroic tale of survival and resilience in the face of impossible odds, Tilar Mazzeo and adapter Mary Cronk Farrell share the true story of this bold and brave woman, overlooked by history, who risked her life to save innocent children from the horrors of the Holocaust.

Excerpt

Irena’s Children

September 1, 1939

The wail of sirens dragged Irena from sleep, and she jumped up. Air-raid sirens. An attack? No. Surely, a false alarm.

She and her mother grabbed their bathrobes and slippers. Everywhere, rumpled neighbors were pouring out of their apartment buildings into the street. They peered upward. It was six o’clock in the morning and the low-lying clouds were calm, the streets empty of traffic. The air-raid wardens knew no more than the curious crowd, but shooed everyone back into their buildings. The anxiety and early hour made people cross, and somewhere in the building a door slammed. The sirens continued to wail.

Irena sat with her mother at the kitchen table and turned on Polish radio. Bleary-eyed and grim, they listened to the news. Everyone feared Germany would strike. Irena and her friends had followed news of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and the antidemocratic policies of his National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi party). The German takeover of Czechoslovakia had moved Poland to ready its military for war. But though Irena had known war would come, it was difficult to believe her country—her city—was under attack!

Hovering over the radio, Irena leaned in to hear the words. Government and city workers in the capital were instructed to stay at their posts around the clock, using all efforts to resist the German aggressors. Thank heavens. Irena wanted to do something.

Irena, stop fidgeting. A look from her mother told her to sit down and finish her coffee. What could she do anyhow? The minutes ticked by. News trickled in. German armies rolled into Poland from the south, the west, and the north.

By 7:00 a.m. Irena could no longer bear doing nothing, and she flew down the stairs to the courtyard. Tossing her weathered bag into the basket of her bicycle, Irena hitched up her skirt and pedaled quickly toward the Old Town and her office on Zlota Street. It was a relief to be off, to leave the waiting and worrying to her mother. She felt a powerful purpose and determination.

Irena worked as a senior administrator in a branch of the city social welfare office that ran soup kitchens across the city. Reaching her building, she went to look for her boss, Irena—“Irka”—Schultz, a thin, birdlike blonde with a big smile. Irka was more than her supervisor. She was one of Dr. Radlinska’s girls, just like Irena was.

While studying at the Polish Free University, Irena had found a warm welcome in Professor Helena Radlinska’s circle. The sturdy woman with thinning white hair shared the socialist ideals of Irena’s papa, and Irena missed her papa. She’d joined in the radical activism of the tight-knit group of young men and women inspired by Dr. Radlinska. And the professor had given Irena her first social work job at one of her clinics helping the poorest families in Warsaw.

Irena found her boss Irka calm and matter-of-fact, even with the city under siege. For the next few hours, the staff set in motion plans for how they might help families survive this crisis. Irena couldn’t imagine what they would face in the coming days. Who knew what war looked like until they were in it? But she knew the families she served would need her help now more than ever.

At about nine o’clock, the women dropped what they were doing. They listened to what sounded like “a faraway surf . . . not a calm surf but when waves crash onto a beach during a storm.” Then air-raid sirens pierced their ears, soon joined by a thunder of planes overhead, and Irena heard the first explosions. Bombs. She and the other women ran for cover, while the building rattled with the hum of planes, tens, maybe even hundreds and ear-splitting, ground-shaking concussions. In the cellar bomb shelters, everyone clutched hands in the musty darkness with a faint hope, listening for the Polish defensive artillery firing back.

When the pounding let up and the roar of bombers receded, it was horrible to see how much damage had been done to Warsaw. Irena looked out at a sky black with smoke. Chaos filled Zlota Street. Clouds of dust coated her throat and smoke stung her nose. Some buildings had been turned to rubble. Flames engulfed the gutted facades of entire apartment buildings. The walls swayed and then toppled in a crash to the cobblestones. Piles of bricks lay everywhere, as if thrown by an angry child, and glass and debris littered the ground. Horses fell dead, and Irena saw, there, in the midst of it all, mangled human bodies.

The first onslaught of war was dizzying, unreal. She could not imagine the horrors that were yet to come, and shuddered to think of the soldiers on the front lines, fighting to stop the Germans, the bloodshed they must be facing. A few days ago, she had said good-bye to several men leaving Warsaw for military deployment. A lawyer in the social services office, Jozef Zysman, had been called up as reserve officer, and Irena worried about his wife, Theodora. He was a prominent city attorney, often representing needy people for free. Irena had regularly waited with him in the halls of the courthouse, each of them leaning up against the stair railings and laughing. He defended people illegally evicted from their homes, and Irena was one of his favorite witnesses. She reveled in righting an injustice and could be very persuasive. She would have to check in on Theodora and their baby.

Amid the utter confusion, Irena tried to clear her mind. It was her job to provide food in this emergency. People bombed out of their homes would need shelter. She and her coworkers set up dozens of makeshift canteens and shelters. They stood by offering hot soup and blankets.

In the following days the assault was continual, flights of up to fifty bombers, exploding warheads, hitting army barracks, targeting factories, and demolishing apartment buildings, hospitals, and schools. No place was safe from the bombs. It felt especially frightening to go out in the street, but Irena had to check on the soup kitchens she had helped organize. The lines of people waiting for food included families with children of all ages, and grandparents, too.

Many had fled the countryside. They told of running from their homes as the war planes flew over their villages, seeing the bombs demolish their homes. German dive bombers screeched overhead, opening fire on the people, the unarmed, helpless people. Survivors came to Warsaw with little but the clothes they wore. Others, they said, never made it to the city.

Irena moved among the refugees, trying to comfort them. Polish and sometimes Yiddish voices surrounded her, broken with sorrow, high pitched with fear, or low with desperation. With dirty, tearstained faces, villagers recounted how they had joined the throngs of people on the roads, no place to go, but at least not alone.

There was nothing to do, they told Irena, but to keep walking. Her heart seized as she learned of the cruelty of the attacking Germans. But then, the Nazis had turned cruelty and violence against Germany’s own people who didn’t go along, like socialists, communists, and especially Jewish people. How could one brave an enemy that showed the innocent no mercy? The refugees’ plight compelled her to work long days procuring food for the soup kitchens, and investigating the ruins of the city for possible shelters for the homeless.

The Jewish families, their children lined up like stair steps, reminded her of her papa’s clinic when she was a child in Otwock. His office had often been filled with the desperate and poor. He had never turned away anyone. When he was tired, he still made rounds in the village. He treated Jewish people when other doctors refused. Her memories of Papa warmed her, for he had doted on her as a child, and in this dark time, his example of compassion became a beacon lighting her way.

Through the week, the intermittent news Irena gleaned from Polish radio did not offer much hope. German tanks and infantry had broken through Polish army defensive lines, scattering whole battalions. Polish forces retreated east in an effort to regroup. On the eighth day of the German attack, Irena learned the enemy now completely surrounded Warsaw.

The news grew worse. On September 17, the Soviet army had invaded Poland’s eastern border, and Irena could hear the artillery as the German army breached Warsaw’s defenses and poured into the city. She had no choice but to take cover as fighting erupted in the streets and the attacks from the air grew more intense.

Some of Irena’s neighbors and coworkers held on to a thread of hope as long as the fighting continued in Warsaw’s neighborhoods, but beginning the morning of September 24, the sky over Warsaw darkened with German bombers, hundreds of them—no, it had to be thousands, so many they couldn’t be counted. Bombs once again exploded in the city without stopping for hours. A full day. Two days. The floor bumped and rolled with the explosions. Surely, she’d go deaf from the incessant booming and blasting. The brown dust and smothering smoke burned Irena’s nose and lungs, stung her eyes.

When the attack finally ended, Irena took stock. From what she could learn, the Germans had clobbered entire districts of Warsaw into ruins. Debris clogged some streets entirely. Whole blocks raged with fire. Would any of them survive?

At home, Irena’s mother whispered urgent prayers. So did Irena. Still, she put more faith in action and there was more work to do than ever. Some of the worst hit areas of the city included the quarter just north of her office. A mostly Jewish neighborhood, it ran from the Jewish and Polish cemeteries on the west, to the great synagogue on the east. Irena found the homeless had crawled into overcrowded cellars, thick with the smell of gangrene, and too many bodies too close. In the air-raid shelters, the injured lay on stretchers, crying quietly and begging for water.

All the people of Warsaw suffered. There was no water, no electricity, and no longer any food. The air was rank with the smell of human and animal corpses heaped in the streets. Some kind souls buried the dead where they found them, in a garden or a square or the courtyards of houses. Famished people cut flesh from horses as soon as they perished, leaving skeletons in the street.

Irena was at the office trying to fight the chaos by establishing order in her soup kitchens when Polish radio announced the news. The mayor had surrendered the city to the Germans. Everyone in the office was crying and hugging, because it was sad and scary. Out on the street an ominous silence settled over Warsaw, eerie after nearly a month of bombardment.

As the facts became clear, the women in the office tried to comfort one another. Germany and the Soviet Union had struck a deal before the bombing started. The two countries divided Poland like two bullies stealing another boy’s marbles and splitting the spoils.

Irena and her friends had a hundred anxious questions. Would the men in the Polish army make it home? And what would they come home to? A smoldering, hungry city burying its dead.

September 1, 1939

The wail of sirens dragged Irena from sleep, and she jumped up. Air-raid sirens. An attack? No. Surely, a false alarm.

She and her mother grabbed their bathrobes and slippers. Everywhere, rumpled neighbors were pouring out of their apartment buildings into the street. They peered upward. It was six o’clock in the morning and the low-lying clouds were calm, the streets empty of traffic. The air-raid wardens knew no more than the curious crowd, but shooed everyone back into their buildings. The anxiety and early hour made people cross, and somewhere in the building a door slammed. The sirens continued to wail.

Irena sat with her mother at the kitchen table and turned on Polish radio. Bleary-eyed and grim, they listened to the news. Everyone feared Germany would strike. Irena and her friends had followed news of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and the antidemocratic policies of his National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi party). The German takeover of Czechoslovakia had moved Poland to ready its military for war. But though Irena had known war would come, it was difficult to believe her country—her city—was under attack!

Hovering over the radio, Irena leaned in to hear the words. Government and city workers in the capital were instructed to stay at their posts around the clock, using all efforts to resist the German aggressors. Thank heavens. Irena wanted to do something.

Irena, stop fidgeting. A look from her mother told her to sit down and finish her coffee. What could she do anyhow? The minutes ticked by. News trickled in. German armies rolled into Poland from the south, the west, and the north.

By 7:00 a.m. Irena could no longer bear doing nothing, and she flew down the stairs to the courtyard. Tossing her weathered bag into the basket of her bicycle, Irena hitched up her skirt and pedaled quickly toward the Old Town and her office on Zlota Street. It was a relief to be off, to leave the waiting and worrying to her mother. She felt a powerful purpose and determination.

Irena worked as a senior administrator in a branch of the city social welfare office that ran soup kitchens across the city. Reaching her building, she went to look for her boss, Irena—“Irka”—Schultz, a thin, birdlike blonde with a big smile. Irka was more than her supervisor. She was one of Dr. Radlinska’s girls, just like Irena was.

While studying at the Polish Free University, Irena had found a warm welcome in Professor Helena Radlinska’s circle. The sturdy woman with thinning white hair shared the socialist ideals of Irena’s papa, and Irena missed her papa. She’d joined in the radical activism of the tight-knit group of young men and women inspired by Dr. Radlinska. And the professor had given Irena her first social work job at one of her clinics helping the poorest families in Warsaw.

Irena found her boss Irka calm and matter-of-fact, even with the city under siege. For the next few hours, the staff set in motion plans for how they might help families survive this crisis. Irena couldn’t imagine what they would face in the coming days. Who knew what war looked like until they were in it? But she knew the families she served would need her help now more than ever.

At about nine o’clock, the women dropped what they were doing. They listened to what sounded like “a faraway surf . . . not a calm surf but when waves crash onto a beach during a storm.” Then air-raid sirens pierced their ears, soon joined by a thunder of planes overhead, and Irena heard the first explosions. Bombs. She and the other women ran for cover, while the building rattled with the hum of planes, tens, maybe even hundreds and ear-splitting, ground-shaking concussions. In the cellar bomb shelters, everyone clutched hands in the musty darkness with a faint hope, listening for the Polish defensive artillery firing back.

When the pounding let up and the roar of bombers receded, it was horrible to see how much damage had been done to Warsaw. Irena looked out at a sky black with smoke. Chaos filled Zlota Street. Clouds of dust coated her throat and smoke stung her nose. Some buildings had been turned to rubble. Flames engulfed the gutted facades of entire apartment buildings. The walls swayed and then toppled in a crash to the cobblestones. Piles of bricks lay everywhere, as if thrown by an angry child, and glass and debris littered the ground. Horses fell dead, and Irena saw, there, in the midst of it all, mangled human bodies.

The first onslaught of war was dizzying, unreal. She could not imagine the horrors that were yet to come, and shuddered to think of the soldiers on the front lines, fighting to stop the Germans, the bloodshed they must be facing. A few days ago, she had said good-bye to several men leaving Warsaw for military deployment. A lawyer in the social services office, Jozef Zysman, had been called up as reserve officer, and Irena worried about his wife, Theodora. He was a prominent city attorney, often representing needy people for free. Irena had regularly waited with him in the halls of the courthouse, each of them leaning up against the stair railings and laughing. He defended people illegally evicted from their homes, and Irena was one of his favorite witnesses. She reveled in righting an injustice and could be very persuasive. She would have to check in on Theodora and their baby.

Amid the utter confusion, Irena tried to clear her mind. It was her job to provide food in this emergency. People bombed out of their homes would need shelter. She and her coworkers set up dozens of makeshift canteens and shelters. They stood by offering hot soup and blankets.

In the following days the assault was continual, flights of up to fifty bombers, exploding warheads, hitting army barracks, targeting factories, and demolishing apartment buildings, hospitals, and schools. No place was safe from the bombs. It felt especially frightening to go out in the street, but Irena had to check on the soup kitchens she had helped organize. The lines of people waiting for food included families with children of all ages, and grandparents, too.

Many had fled the countryside. They told of running from their homes as the war planes flew over their villages, seeing the bombs demolish their homes. German dive bombers screeched overhead, opening fire on the people, the unarmed, helpless people. Survivors came to Warsaw with little but the clothes they wore. Others, they said, never made it to the city.

Irena moved among the refugees, trying to comfort them. Polish and sometimes Yiddish voices surrounded her, broken with sorrow, high pitched with fear, or low with desperation. With dirty, tearstained faces, villagers recounted how they had joined the throngs of people on the roads, no place to go, but at least not alone.

There was nothing to do, they told Irena, but to keep walking. Her heart seized as she learned of the cruelty of the attacking Germans. But then, the Nazis had turned cruelty and violence against Germany’s own people who didn’t go along, like socialists, communists, and especially Jewish people. How could one brave an enemy that showed the innocent no mercy? The refugees’ plight compelled her to work long days procuring food for the soup kitchens, and investigating the ruins of the city for possible shelters for the homeless.

The Jewish families, their children lined up like stair steps, reminded her of her papa’s clinic when she was a child in Otwock. His office had often been filled with the desperate and poor. He had never turned away anyone. When he was tired, he still made rounds in the village. He treated Jewish people when other doctors refused. Her memories of Papa warmed her, for he had doted on her as a child, and in this dark time, his example of compassion became a beacon lighting her way.

Through the week, the intermittent news Irena gleaned from Polish radio did not offer much hope. German tanks and infantry had broken through Polish army defensive lines, scattering whole battalions. Polish forces retreated east in an effort to regroup. On the eighth day of the German attack, Irena learned the enemy now completely surrounded Warsaw.

The news grew worse. On September 17, the Soviet army had invaded Poland’s eastern border, and Irena could hear the artillery as the German army breached Warsaw’s defenses and poured into the city. She had no choice but to take cover as fighting erupted in the streets and the attacks from the air grew more intense.

Some of Irena’s neighbors and coworkers held on to a thread of hope as long as the fighting continued in Warsaw’s neighborhoods, but beginning the morning of September 24, the sky over Warsaw darkened with German bombers, hundreds of them—no, it had to be thousands, so many they couldn’t be counted. Bombs once again exploded in the city without stopping for hours. A full day. Two days. The floor bumped and rolled with the explosions. Surely, she’d go deaf from the incessant booming and blasting. The brown dust and smothering smoke burned Irena’s nose and lungs, stung her eyes.

When the attack finally ended, Irena took stock. From what she could learn, the Germans had clobbered entire districts of Warsaw into ruins. Debris clogged some streets entirely. Whole blocks raged with fire. Would any of them survive?

At home, Irena’s mother whispered urgent prayers. So did Irena. Still, she put more faith in action and there was more work to do than ever. Some of the worst hit areas of the city included the quarter just north of her office. A mostly Jewish neighborhood, it ran from the Jewish and Polish cemeteries on the west, to the great synagogue on the east. Irena found the homeless had crawled into overcrowded cellars, thick with the smell of gangrene, and too many bodies too close. In the air-raid shelters, the injured lay on stretchers, crying quietly and begging for water.

All the people of Warsaw suffered. There was no water, no electricity, and no longer any food. The air was rank with the smell of human and animal corpses heaped in the streets. Some kind souls buried the dead where they found them, in a garden or a square or the courtyards of houses. Famished people cut flesh from horses as soon as they perished, leaving skeletons in the street.

Irena was at the office trying to fight the chaos by establishing order in her soup kitchens when Polish radio announced the news. The mayor had surrendered the city to the Germans. Everyone in the office was crying and hugging, because it was sad and scary. Out on the street an ominous silence settled over Warsaw, eerie after nearly a month of bombardment.

As the facts became clear, the women in the office tried to comfort one another. Germany and the Soviet Union had struck a deal before the bombing started. The two countries divided Poland like two bullies stealing another boy’s marbles and splitting the spoils.

Irena and her friends had a hundred anxious questions. Would the men in the Polish army make it home? And what would they come home to? A smoldering, hungry city burying its dead.

Product Details

- Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (September 26, 2017)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481449922

- Grades: 5 and up

- Ages: 10 - 99

- Lexile ® 1000L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Farrell’s adaptation of Mazzeo’s adult title (2016) clearly presents [Irena Sendler’s] life and the ever present reality of death in a sobering, heartbreaking narrative. Readers will understand how Sendler came to be honored by Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.”

– Kirkus Reviews

Awards and Honors

- CCBC Choices (Cooperative Children's Book Council)

- CBC/NCSS Notable Social Studies Trade Book

- Bank Street Best Books of the Year

- Sydney Taylor Notable Book

- Vine Awards for Canadian Jewish Literature - Children/Young Adults Finalist

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Irena's Children Trade Paperback 9781481449922

- Author Photo (jpg): Tilar J. Mazzeo Photography courtesy of author(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit