Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

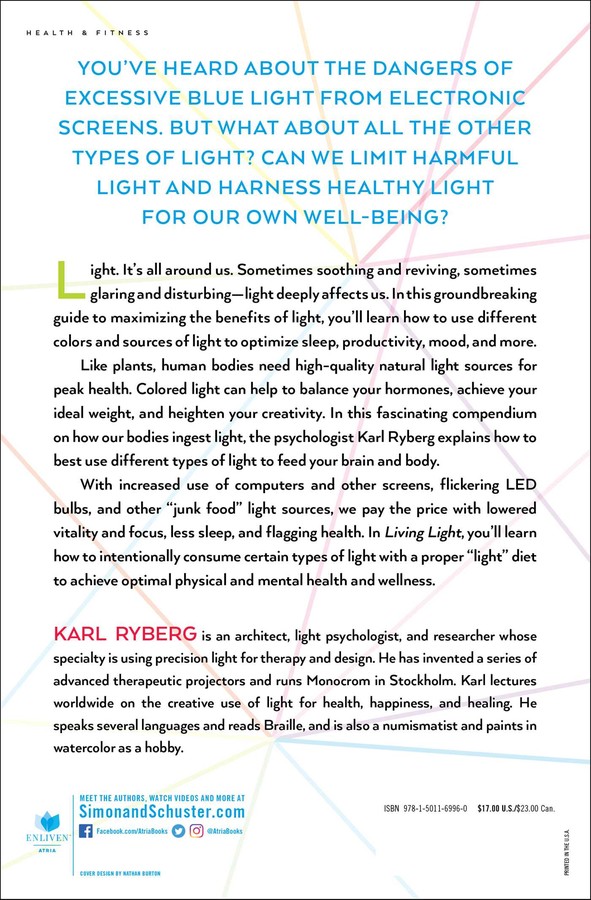

Light. It’s all around us. Sometimes soothing and reviving, sometimes glaring and disturbing—light deeply affects us. But can we harness it for our own well-being?

Like plants, human bodies need quality light in order to survive, regenerate, and thrive. In this fascinating guide to “eating light” psychologist Karl Ryberg shows you how to best use different types of light to feed your brain and body.

Discover how your brain and body absorbs light photons in the form of sunshine, fire, and artificial light. With increased use of computers and screens, flickering LED products, and other “junk food” light sources, we have been paying the price with lowered vitality, focus, and flagging health. By intentionally consuming certain types of light with a proper “diet”, you can alleviate these issues.

Ryberg shows us practical ways to maximize the benefits of light therapy for our own bodies, and how to choose light sources that don’t harm the environment. No matter your age, location, or fitness level, Living Light has timely advice on a range of topics, from remedying light starvation or overload to adopting routines to suit your individual needs.

Written from a lifetime of research on light and biology, this book provides you with a vital understanding of your body clock, brain function, the importance of color, and much more, all in a clear and accessible manner.

Excerpt

MY PERSONAL LIGHT JOURNEY

My fascination with light started when I was a young boy growing up in Sweden. Dad was a cubist painter and worked on large canvases, to which he applied shiny layers of smelly oil paint. His atelier had large windows, facing north, toward the sky, and they gave the whole room a quality of transparency; he was always stressing the necessity of good daylight to get the subtle gradations of color right. I loved to spend time in that spacious studio, and somehow became fascinated with the shimmering interaction of light and color. Eventually I made crude attempts at painting, and a whole new world opened up before my eyes.

As I looked into the interplay of light and color, I wanted to find out more about the nature of this visual magic. This journey led me to study architecture as a young man. But if I thought my studies would help me to understand and indeed to learn more about the wonders of natural light, I was mistaken. It was the 1960s, after all, and the architectural approach to light was blunt and practical, and focused on artificial light; electric lamps were technical commodities to be switched on and off without any further thought. The outflow of light was promptly measured in watts and lux, the building blocks of electric light, and even though we humans were the end users of these technical wonders, there was very little mention of how they might affect us, emotionally or biologically. It was simply something that architects, and indeed consumers, didn’t think about at that time.

Those of us old enough to remember will understand that those were the days of frantic modernism, of looking forward to a bold future, a brave new world in which machines would swiftly solve most of our problems. Nature was shamelessly tamed or maimed, and fluctuating daylight was considered an erratic and uncontrollable nuisance, best barred from organized life. In my native Sweden, futuristic schools were built without any windows at all to create a generation of standardized and brave new kids. The thinking at the time was that steady artificial light would enhance the process of concentration, and that the separation of humans from the world would improve their intellectual performance—but the outcome was a complete disaster. My country started to churn out a generation of children with poor intellectual performance: until 2015, Sweden languished on the lower rungs of the educational ladder, with averages in science, mathematics, and reading lower than those for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The political explanations are many, but, in my view, they neglect the impact of one key factor: lighting.

However, it was my very nationality that fueled my interest in all things light. As we know, Swedes occupy an extreme climate zone with huge luminous contrasts between seasons. This puts a definite strain on our biology, and mood swings are part of the game for many of us. In summer we are bathed in continual light and the sun doesn’t even bother to set. Migratory birds come all the way from Africa to lay their eggs and enjoy the extravagant luminosity, and we Swedes celebrate the festival of Midsummer with eating, dancing, and great celebration. Nordic winters are another story altogether, with long, dark nights and barely any daylight at all. The looming shadows hang on for months. Many of us northerners hibernate indoors and binge on sweet carbohydrates by cozy candlelight. Alcohol is imbibed for additional consolation. The winter blues are a stark reality as the life juices slowly wane away. In Sweden, much of the population eagerly awaits the light of spring to recharge their batteries. The situation is more or less the same in the subarctic regions of northern Canada and Russia.

After finishing my studies, I went to work as an architect in Australia and New Zealand, where the light conditions are vastly different from those in Scandinavia. The luminous effects on people were enormous, and my curiosity about the effects of natural light led me to study psychology and medicine to find out more.

As I wrote my thesis on light therapy, I kept coming across the name Rosenthal in scientific papers. His research was revolutionary and literally shed new light on an old problem. Every Scandinavian knew of the dreaded winter depression, but no real remedy had been found. Women, with their naturally keen color vision, were much more affected than men, but traditional medicine would turn a blind eye and treat it as a collective form of female hysteria. Not until 1984 did Dr. Norman Rosenthal understand what we now know to be seasonal affective disorder, or SAD for short. Under the influence of darkness, the brain will produce the sleep hormone melatonin. This ancient habit worked fine for our African ancestors, because they lived near the equator and their climate came with little seasonal variation, but you can imagine its impact on those of us who live in the Northern Hemisphere. In winter we would be sleepy for months on end! Moving entire populations back to the equator is, of course, an impossibility, so Rosenthal came up with the bright idea of using strong light to simulate sunshine and to stimulate hormones to get the brain back in shape. Somehow, his optic trickery seemed to work.

This was groundbreaking news. At last, someone had proven a clear connection between the level of ambient light and our mental health. Having returned to Sweden, I continued my studies in psychology to gain a better understanding of light and its effects on the human mind. To help in funding my studies, I opened a light clinic in Stockholm offering treatments with the new method. I called it monocrom, meaning “single color,” and over the years my small practice has developed as I have learned more about the transformative qualities of light.

Dr. Rosenthal had recommended using white electric light in large doses to imitate daylight. White rooms in all light clinics were flooded with several thousand lux and the patients were supposed to wear white, too. The visual effect was quite stunning, as you can imagine. However, at the time, the only available sources of sufficient power were large fluorescent tubes, and even though they were effective in improving my clients’ moods, people were less enthusiastic about all that ugly glare.

As a compromise, I started wrapping the fluorescent tubes in colored filters to provide more pleasant visual treatments, and I discovered that the purer and more radiant the colors, the happier my clients would be. The most beautiful colors are known as monochromatic, and these gorgeous eye-catchers are found in rainbows and peacock feathers. Monochromatic in this sense means strictly one-colored as opposed to polychromatic, or many-colored. The pure hues are technically difficult to achieve, but, after some searching, I found highly selective filter coatings that could deliver super light to my clients. The therapeutic outcomes were stunning. Empirically, I found that monochromatic light delivered better results more efficiently, with many clients reporting great benefits, such as incredible lifts in their mood, and many cases of winter blues could be alleviated or totally avoided.

My work in light therapy was going well, but I knew that more could be done. Coincidentally, at this time, I read a fascinating article in an international scientific journal, mentioning a Russian professor at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, Tiina Karu. She was doing research on the cellular responses to monochromatic light and her results were nothing short of revolutionary. Many biological effects of colored mono-light were proven identical to those of the miraculous laser, which was used medically in Eastern Europe at the time. Brain tissue was shown to be particularly sensitive to laser radiation, and intellectual performance would improve. Diffused laser light could also induce rapid wound healing and regeneration of skin tissue. The wounds treated with laser left no scars, and this was a huge cosmetic success. The Hungarian professor Endre Mester made one of the key discoveries in this field, finding that low-level laser therapy (LLLT) produced great results for pain-related conditions such as osteoarthritis. The biological effects of strictly one-colored—or monochromatic—light are identical or even better than laser light. (For nonbiological purposes like engineering or physics, they are not identical at all.)

Fortunately, it was the time of glasnost in the former Soviet Union, and President Mikhail Gorbachev had initiated a program of cultural exchange that was exceptionally open-minded, so I wrote to Professor Karu and invited myself over as a guest student. Snail mail was the norm in those days, and the response took a long while, but eventually a kind letter of invitation arrived, and soon I was on board an Aeroflot plane bound for Moscow.

Professor Karu welcomed me to Russia and personally guided me around the laboratories. I was fascinated to see the large halls with high ceilings filled with glass cabinets containing hordes of transparent vials and glowing lasers. One of her key discoveries was that monochromatic light can repair damaged mitochondrial DNA, which is the very powerhouse of the living cell. This irradiation will extend the normal life span of the entire cell, but what was crucial was the purity of the color. We will look at the technical side of things in chapter 2, but, in short, I learned that biological laser effects could be replicated by the monochromatic light I was already using. I couldn’t wait to get back and upgrade my therapeutic equipment so that I could replicate—albeit on a smaller scale—what Professor Karu was doing in the Soviet Union.

With the help of my team of technicians, a new generation of professional color projectors could now be manufactured. High-pressure xenon bulbs—the kind of bulbs normally found in cinema projectors—were needed as light sources, and the light parameters had to be accurately defined. The optics were quite complicated, and in the beginning brilliant failures were produced. Finally we got the technical details right and could at last present this modern version of light therapy to our clients, at this time presenting with a range of issues, including sleeplessness, insomnia, depression, and even infertility. Clients and colleagues alike were surprised at the capacity of the new projection methods to be beautiful, restful, and healing. As many of us know, happiness and beauty are extremely powerful healing factors—extending far beyond their famed placebo effects. They give hope to the heart and form the very basis of successful psychotherapy, but today we also know that joyous states of mind are linked to cell repair. In response to emotions of happiness, it has been discovered that the brain starts to produce powerful healing hormones like endorphins and oxytocin, which are released into the bloodstream. This will ultimately affect the entire body.

In the case of my work, the positive therapeutic results came as a boost to us all, and the almighty grapevine did the rest. Word started to spread about our glorious Nordic Light and we began exporting the equipment. It became really popular, and thousands of people experienced the healing effects of mono-light. More photonic tools were added to the list, and I finally had to close my private clinic to meet the growing demand and to train new generations of light workers. Competent researchers were widely scattered, so an international network and association was established, the International Light Association. No university offered any systematic training in the enigmatic science of light therapy. It was definitely a fringe discipline, and accessible literature on the subject was largely lacking. Old books and articles had to be plowed through, and new books and articles had to be written. Everyone knew what light meant—but offering light therapy as a remedy for body and soul was not a widespread idea.

Which brings me to Living Light and what my work, distilled in this book, can do for you. It’s true to say that not all of us suffer from SAD or from other ailments that might respond to light therapy; not all of us experience depression or stress, thankfully, but it is my belief that good-quality light in our daily lives is far more important than we might think. Thankfully, the research is beginning to emerge to support my long-held views, which is gratifying, of course, but also of immediate importance to you, the reader. Enjoying the precious resource that is natural light will add so much more to your life: it will boost your reserves of vitamin D, but it will also make you feel so much better. And gaining insights into the role of electric light—and in particular the blue light that now dominates our lives—will help you to minimize its negative effects.

Understanding how your eyes work to absorb natural light and to see will be fascinating, but it will also help you in practical ways. The eye yoga exercises in this book might strike you as being a bit “out there” at first, but they are fun, relaxing, and might just help to keep your eye muscles in tip-top shape.

Understanding how natural light works in architecture will help you to use it well in your own home, whether you’ve been lucky enough to build it yourself or are living in an older home—many gloomy décor problems that seem insurmountable are easily conquered with a little well-placed illumination. And eating a nice, balanced “light” diet will not only help you to maximize your vitamin and mineral intake, but will also keep you feeling healthy and vital. Finally, the “color gallery” in this book’s appendix will help you to understand more about the magic of color and how important it is in all our lives.

Living Light is the culmination of many years of work. For me, it’s the fulfillment of a life’s dream to be able to share my passion for light with you—it’s a cookbook of sorts for a happy and luminous life. This is where my part of the journey ends. The rest is for you to enjoy.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria/Enliven Books (February 5, 2019)

- Length: 192 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501169960

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Some of these claims seem radical at first, but Ryberg backs them up...Ryberg offers a comprehensive background...A concise book packed with insights into human biology and psychology, the science of light and how the two intersect in our day-to-day lives—whether we recognize it or not."

– Shelf Awareness

"No matter your age, location, or fitness level, Living Light has timely advice...Written from a lifetime of research on light and biology, this book provides you with a vital understanding of your body clock, brain function, the importance of color, and much more, all in a clear and accessible manner."

– Edge Magazine

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Living Light Trade Paperback 9781501169960