Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

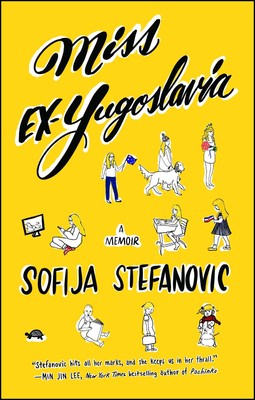

About The Book

Sofija Stefanovic makes the first of many awkward entrances in 1982, when she is born in socialist Yugoslavia. The circumstances of her birth (a blackout, gasoline shortages, bickering parents) don’t exactly get her off to a running start. While around her, ethnic tensions are stoked by totalitarian leaders with violent agendas, Stefanovic’s early life is filled with Yugo rock, inadvisable crushes, and the quirky ups and downs of life in a socialist state.

As the political situation grows more dire, the Stefanovics travel back and forth between faraway, peaceful Australia, where they can’t seem to fit in, and their turbulent homeland, which they can’t seem to shake. Meanwhile, Yugoslavia collapses into the bloodiest European conflict in recent history.

Featuring warlords and beauty queens, tiger cubs and Baby-Sitters Clubs, Sofija Stefanovic’s memoir is a window to a complicated culture that she both cherishes and resents. Revealing war and immigration from the crucial viewpoint of women and children, Stefanovic chronicles her own coming-of-age, both as a woman and as an artist. Refreshingly candid, poignant, and illuminating, “Stefanovic’s story is as unique and wacky as it is important” (Esquire).

Excerpt

I wouldn’t normally enter a beauty pageant, but this one is special. It’s a battle for the title of Miss Ex-Yugoslavia, beauty queen of a country that no longer exists. It is due to the country being “no more” that our shoddy little contest is happening in Australia, over eight thousand miles from where Yugoslavia once stood. My fellow competitors and I are immigrants and refugees, coming from different sides of the conflict that split Yugoslavia up. It’s a weird idea for a competition—bringing young women from a war-torn country together to be objectified, but in our little diaspora, we’re used to contradictions.

It’s 2005, I’m twenty-two, and I’ve been living in Australia for most of my life. I’m at Joy, an empty Melbourne nightclub that smells of stale smoke and is located above a fruit-and-vegetable market. I open the door to the dressing room, and when my eyes adjust to the fluorescent lights I see that young women are rubbing olive oil on each other’s thighs. Apparently, this is a trick used in “real” competitions, one we’ve hijacked for our amateur version. For weeks, I’ve been preparing myself to stand almost naked in front of everyone I know, and it’s come around quick. As I scan the shiny bodies for my friend Nina, I’m dismayed to see that all the other girls have dead-straight hair, while mine, thanks to an overzealous hairdresser with a curling wand, looks like a wig made of sausages.

“Doi, lutko” (“Come here, doll”), Nina says as she emerges from the crowd of girls. “Maybe we can straighten it.” She brings her hand up to my hair cautiously, as if petting a startled lamb. Nina is a Bosnian refugee in a miniskirt. As a contestant, she is technically my competitor, but we’ve become close in the rehearsals leading up to the pageant.

Under Nina’s tentative pets, the hair doesn’t give. It’s been sprayed to stay like this, possibly forever. I shift uncomfortably and tug on the hem of my skirt, trying to pull it lower. Just like the hair, it doesn’t budge. In my language, such micro-skirts have earned their own graphic term: dopičnjak, which literally means “to the pussy”—a precise term to distinguish the dopičnjak from its more conservative subgenital cousin, the miniskirt.

Though several of us barely speak our mother tongue, all of us competitors are ex-Yugos, for better or worse; we come from Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. I join a conversation in which Yugo girls are yelling over one another in slang-riddled English, recalling munching on the salty peanut snack Smoki when they were little, agreeing that it was “the bomb” and “totally sick,” superior to anything one might find in our adoptive home of Australia.

The idea of a beauty pageant freaks me out, and ex-Yugoslavia as a country is itself an oxymoron—but the combination of the two makes the deliciously weird Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition the ideal subject for my documentary film class. I feel like a double agent. Yes, I’m part of the ex-Yugo community, but also I’m a cynical, story-hungry, Western-schooled film student, and so I’ve gone undercover among my own people. I know my community is strange, and I want to get top marks for this exclusive glimpse within. Though I’ve been deriding the competition to my film-student friends, rolling my eyes at the ironies, I have to admit that this pageant, and its resurrection of my zombie country, is actually poking at something deep.

If I’m honest with myself, I’m not just a filmmaker seeking a story. This is my community. I want outsiders to see the human face of ex-Yugoslavia, because it’s my face, and the face of these girls. We’re more than news reports about war and ethnic cleansing.

“Who prefers to speak English to the camera?” I ask the room, in English, whipping my sausage-curled head around, as my college classmate Maggie points the camera at the other contestants backstage.

“Me!” most of the girls say in chorus.

“What’s your opinion of ex-Yugoslavia?” I ask Zora, the seventeen-year-old from Montenegro.

“Um, I don’t know,” she says.

“It’s complicated!” someone else calls out.

As a filmmaker, I want a neat sound bite, but ex-Yugoslavia is unwieldy. Most of my fellow contestants are confused about the turbulent history of the region, and it’s not easy to explain in a nutshell. At the very least, I want viewers to understand what brought us here: the wars that consumed the 1990s, whose main players were Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina—the three largest republics within the Yugoslav Federation.

Like many families, mine left when the wars began, and like the rest of the Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competitors, I was only a kid. Despite the passage of time, being part of an immigrant minority in Australia, speaking Serbian at home, being all too familiar with dopičnjaks, I’m embedded in the ex-Yugoslavian community. Yugoslavia, and its mini-skirt-wearing war-prone people, have weighed upon me my whole life.

Most of these young women moved to Australia either as immigrants seeking a better life (like my family, who came from Serbia), or as refugees fleeing the effects of war (like the Croatian and Bosnian girls).

“Why are you competing for Miss Ex-Yugoslavia?” I prod Zora.

“That’s where I come from,” she says, looking down, like I’m a demanding schoolteacher. “And my parents want me to.”

• • •

In the student film I’m making, I plan to contextualize the footage of the Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition with my own story. I’ve put together some home footage of me in Belgrade, before we moved to Australia. The footage shows me aged two, in a blue terry-cloth romper handed down from my cousins. I’m in front of our scruffy building on the Boulevard of Revolution, posing proudly on the hood of my parents’ tiny red Fiat, with my little legs crossed like a glamorous grown-up’s. To accompany these scenes, I’ve inserted voice-over narration, which says, “The Belgrade I left is still my home. I was born there and I plan to die there.” But really, though I like the dramatic way it sounds, I’m not sure it’s true. Would I really go back to that poor, corrupt, dirty place, now that English comes easier to me than Serbian?

I am quick to tell anyone who asks that I find beauty pageants stupid and that I’m competing for the sake of journalism. However, I am still a human living in the world, and I would like to look hot. I’ve had my body waxed, I’ve been taught how to walk down a runway, and I’ve eaten nothing except celery and tuna for weeks, in the desperate hope that it will reduce my cellulite. I’ve replaced my nerdy glasses with contacts, and I’m the fittest I’ve been in my life. A secret, embarrassed little part of me that always wanted to be a princess is fluttering with hope. I’ve reverted to childhood habits of craving attention, and, for a second, I forget all the things I dislike about my appearance. As I observe my fake-tanned, shiny body in the mirror and smile with my whitened teeth, I think, What if somehow, some way, I actually win Miss Ex-Yugoslavia? I allow myself to dream for a moment about being a crowned princess, like the ones in the Disney tapes my dad would get for me on the black market in socialist Yugoslavia.

• • •

This highly amateur competition is the brainchild of a man named Sasha, who organizes social events for the ex-Yugoslavian community. He has managed to gather nine competitors aged sixteen to twenty-three who found out about the event through the ex-Yugo grapevine: a poster at the Montenegrin doctor’s office, an advertisement in the Serbian Voice local newspaper, their parents, chatter in the Yugo clubs where young people go to connect with the community.

Sasha is Serbian, like me. Earlier today, he was bustling around the nightclub with his slicked-back hair and leather jacket, ordering people to set up the runway. I pointed a camera at him and, like a hard-hitting journalist glistening with recently applied spray tan that left orange marks on the wall, asked, in our language, why he decided to stage a Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition.

Sasha turned to the camera with a practiced smile and said, “I’m simply trying to bring these girls together. What happened to Yugoslavia is, unfortunately, a wound that remains in our minds and in our hearts. But now we’re here, on another planet, so let’s treat it that way. Let’s be friends.”

“Do you think we will all get along?” I asked, hoping he’d address the wars he was tiptoeing around.

“I don’t know, but I’m willing to try. I am only interested in business, not in politics.” He looked at the camera to reiterate, to make sure he wasn’t antagonizing any party: “I say that for the record, I am only interested in business and nothing else.”

His interest in business is so keen in fact, that he’s making me give him my footage after tonight. He is planning to make a DVD of the pageant, separate from my documentary. Unlike my film, with which I hope to encapsulate the troubled history of Yugoslavia in under ten minutes, he intends to skip the politics altogether. Instead, he will pair footage of us girls in skimpy outfits with dance music and then sell the DVD back to us and our families for fifty dollars.

Now it’s eight o’clock, and the peace Sasha was hoping for reigns in the dressing room. Here, girls help each other with their hair, they attach safety pins to hemlines, and share Band-Aids to stop blisters. The event was supposed to begin an hour ago, but we are still waiting for audience members to be seated. There’s a security guard who is searching each guest with a handheld metal detector downstairs, and I suspect it’s taking so long because all the gold chains are setting it off.

• • •

My camera operator, Maggie, asks me quietly who she should be getting the most footage of, meaning, who’s likely to win this thing? I think it will be Nina from Bosnia. She’s not soft and fresh-faced like Zora from Montenegro, but she is certainly one of the most beautiful competitors. She is very thin, with big eyes, high cheekbones, and a pointed chin. Nina reminds me of the young woman in Disney’s The Little Mermaid who turns out to be Ursula the witch in disguise, which is to say, she’s both attractive and a little dangerous. At rehearsal, she casually mentioned getting into a fight with some girls at a club, to the awe of some of the more straightlaced competitors (myself included). Nina is wise, in many ways more mature than the rest of us, and I’m simultaneously drawn to her and repelled by her. With her gaze that is always calm, almost lethargic, she makes me feel especially neurotic and weird. And she isn’t nervous about going onstage to be ogled—she’s got a clear purpose in mind: “Definitely the ticket,” she tells Maggie when asked about her motivation for competing. The winner of Miss Ex-Yugoslavia will receive a ticket back home, to whichever part of that former country she desires, and Nina is itching to visit Sarajevo, which she left ten years ago when it was a bloody mess.

Partly, it’s my guilt—for not experiencing war firsthand, for having been born in Belgrade instead of Sarajevo—that makes me crave Nina’s affection. My family left not because our lives were in danger, but because my parents wanted their daughters to have opportunities greater than those offered in wartime Yugoslavia. I know that Nina and I share ex-Yugoslavia, but the piece that belongs to her is more damaged than the piece that belongs to me. I wonder if she feels this injustice too, if she has a desire to punish me for the privileges I had, as I, deep down, feel a need to be punished.

“I can talk about being injured by a Serbian bomb if that would be good for the film,” Nina offers, and as Maggie pivots her camera to face her, there’s a knock at the dressing-room door, and Sasha pops his head in. Tina from Slovenia, the only blonde among a sea of brunettes, addresses the camera in English, like an on-the-ground reporter.

“That’s Sasha, the organizer of the event.”

“Just pretend the camera isn’t here,” I say, with a touch of irritation, as I’ve explained this about a thousand times already, and I have a specific vision for this film, namely, for it to look like a fly-on-the-wall masterpiece of observational cinema.

“Are you ladies ready?” Sasha says, in his accented English, staring straight at the camera, confirming that this will not be a fly-on-the-wall masterpiece after all. He clears his throat and continues his down-the-barrel address. “Now, you all know there is only one winner tonight,” he says, and I imagine he’s prepared this speech so that he can include it in his fifty-dollar DVD.

“You are all beautiful,” he says with gravity, sweeping across the room with one arm. “But my job is only—for one winner. To . . . give her the crown.” He pauses, as if confused by his own clumsy turn of phrase. “That is my job. You have five minutes,” he says solemnly, hurriedly exiting the room and closing the door, as an excited cry rises from the girls, who rush to put the finishing touches on their outfits.

I ask Maggie to follow Sasha and capture some footage of the nightclub filling with hundreds of people. She comes back minutes later, with a worried look. She says she opened the door of the staff bathroom, and interrupted two businessmen snorting cocaine. Those who have seen the mafia portrayed in popular culture would be forgiven for thinking that half the people at Joy tonight are involved in organized crime. And considering how brutal the Yugoslavian wars were, an observer might also wonder—how many of these tall, strong men, in their leather jackets and open-collared shirts, were involved in the violence?

I peek out of the dressing room door to watch the patrons, who have all paid thirty-five dollars a ticket and are demanding the free glass of champagne they were promised on arrival.

I know that some of the people in this room, all dressed up, smoking cigarettes and knocking back Šljivovica plum brandy, were ethnically cleansed from their villages. When they were fleeing to refugee camps, starving under house arrest, or huddled in basements to avoid bombs, could they have guessed they’d end up here years later, in a club on the other side of the earth surrounded by ex-Yugoslavians from all sides of the war? Yet here they all are, waiting to pick a queen among the young women who will soon be parading their flesh onstage, in a country where bodies are not in danger of being blown up. If they are thinking these things, people aren’t saying them. The horrors of war are generally something people keep to themselves; they are the secrets that wake them up at night, not topics to be discussed on a Friday night out, when turbo-folk music is pumping.

The person who knows these secrets best—what people did to one another in the war—is sitting out there tonight. From my vantage point, I can just make her out, her heavy frame coming into focus through a cloud of cigarette smoke. It’s my mother. She’s at a table surrounded by her friends, and every now and then, as if she’s Marlon Brando in The Godfather, someone comes up to her. They’re saying, “My respects, Dr. Koka,” which is what they call her, even though she’s not a doctor. Thanks to my mother’s status as beloved counselor, I am, by default, respected in the community, too.

“Dr. Koka’s older daughter is competing tonight,” people are saying to their friends. I know it already, people are resolved to cheer loudly when I take the stage, out of love for my mother.

I spot another member of my crew, Luke, who I’ve enlisted to record sound. “This is like a Kusturica film,” Luke says with glee, when I wave him over to the dressing room. He’s a fan of the Serbian director who is known for the surreal depictions of ex-Yugoslavians. Luke looks around at my community, clearly hoping a pig will appear and start gnawing at the bar, or that someone will smash a bottle over his own head.

Sasha waves—it’s time. The first stage of the competition, Casual Wear, is in fact just an opportunity to get up onstage wearing a miniskirt and a T-shirt advertising Sasha’s Yugo events business. At the last minute, Nina comes up with the genius idea of tying the front of our T-shirts in a knot, allowing us to show off our midriffs, and at the same time to quietly sabotage Sasha’s attempt to turn us into commercials. We follow her lead. As we rehearsed, we walk single-file out of the dressing room. There is no actual “backstage” area, so the audience can see us as we walk out and stand in line at the side of the stage, waiting to be introduced. Already, it’s embarrassing; as all eyes turn to us, we hear the whooping calls of boyfriends, family, and friends, and the whistles from strangers, while we stare straight ahead.

• • •

The emcees take the stage. Sasha planned on finding hosts from two ex-Yugoslavian countries, but it seems we have ended up with a random host-for-hire called Monica, a “true blue” Australian in a red cocktail dress, and a confused Serbian man in a suit named Bane, who I suspect is onstage not for his charisma but because he is a friend of Sasha’s.

“Are you ready to go crazy and cheer for some babes!?” Monica screams, and the crowd answers with a roar. Does Monica know what ex-Yugoslavia is, who these tall, shouty foreigners are? Perhaps she doesn’t care, and is just here to do her job: get the crowd worked up, make a couple hundred dollars, and then walk out of Joy and never think again about this little community. She could just as easily be hosting a dog show, a bake-off, or a bingo night. I think how liberating it would be to be a regular Aussie and stand in Monica’s position—able to free myself of the ties that bind me to everyone in this room, even people I’ve never met, but whom I feel obliged to hug and kiss, because we come from the same troubled little piece of earth.

I notice a man waving enthusiastically, and it takes me a second to recognize him as a patient who had a cyst removed from his groin last week. I’d been working my weekend shift at Peter the doctor’s clinic and was required to hold a little sterilized dish while the offending cyst was removed. I wave back. As if the sudden change from “groin-cyst patient and disgusted assistant” to “ogler and oiled-up young woman” were a perfectly normal progression of our relationship.

“Let’s bring these girls up here, one by one. Can I hear a big round of applause for Contestant Number One!?” Monica shouts, and Nina steps lithely onto the stage, the pointy heels of her knee-high boots holding steady as she strides down the runway. She pauses at the end, puts a hand on her hip, raises a thin, arched eyebrow, and smiles at the judges. That’s how you do it, I find myself thinking, as if I’m a beauty-show connoisseur.

“Let’s hear it for Nina, from Sarajevo!” Bane says. The resounding cheer from the audience can be largely attributed to her fellow Sarajevans, refugees who make their presence known with whistles and shouts of solidarity. Many non-natives also cheer in support of Sarajevo, knowing what that city endured during the war.

• • •

Onstage, Nina smiles and blows a kiss to her fans, receiving applause so thunderous it makes the floor shake.

The crowd is riled up. They’ve been drinking, and shouting, and when Zora from Montenegro takes the stage, she too receives an uproarious welcome.

Montenegro is mountainous and beachy, war-free, and once a vacation destination for many Yugoslavians. Montenegrins are known for being tall and dark, and Zora’s height, her tan, the nearly black hair that falls down her back like a horse’s mane, are a definite hit with the crowd.

When it’s my turn to go up, I take the stairs carefully, remembering that I slipped during rehearsal and praying I don’t repeat the humiliation. I don’t like taking chances, so I walk at half the pace of everyone else, out of time with the pop music that plays. The applause slows, but not in a mocking way—the crowd simply matches it to the speed at which I’m walking, clapping to a beat that propels me along. I get to the end of the runway, and mouth hvala at the crowd, which means “thank you,” and I am answered with whistles and cheers. I’m supposed to greet the judges, so I nod to one of them, Peter the doctor, a dark Montenegrin in an Armani suit. He’s told me sternly not to expect special treatment just because I work at his clinic—most of the other girls and their families are his patients. Beside him is the middle-aged Macedonian owner of Joy nightclub. At the end of the judging table is the woman who runs Fantastic Face Beauty School. Two of her students were conscripted to do our makeup, and I find her regarding my hair, trying to work out if I’m wearing a wig. I toss my head, attempting to flick my hair over my shoulder as I’ve seen other girls do, but it barely moves. One of the sausages just hits me gently on the side of the face, and I turn inexpertly on my spiky heel, making my retreat slowly back down the runway.

• • •

Backstage, everyone is euphoric, thrilled by the positive reaction of the crowd. We have half an hour before we’re onstage again, for the Evening Wear portion of the show. I’ll be wearing a long red silky dress, which I bought with the intention of returning to the store tomorrow and getting my money back. Someone points out that the patrons are eating ćevapčići—delicious skinless sausages—and we realize that, even though we’ve been here for hours, no one has offered us anything to eat. Sasha promises to bring us food, and as we wait, Zora and a couple of others start preparing for the next part of the evening, during which we will be asked questions.

“Describe yourself,” one of the girls quizzes Zora, as the sausages arrive and we pick them up daintily with our fingers.

“I’m ambitious, confident . . .” Zora says, then rolls her eyes. “Yeah, right.”

To avoid staining a dress I don’t actually own with a greasy skinless sausage, I stay in my casual wear for a bit longer. I slide onto the floor next to Nina, and we chat in a mix of English and our native languages, both of them varieties of Serbo-Croatian—for me Serbian, with my clipped Belgrade accent, for her Bosnian, with her melodic Sarajevo accent. Before the wars started, when Nina and I were kids, Yugoslavia was held together under the optimistic slogan of “Brotherhood and Unity.”

Yugoslavia, which had been formed after World War I as part of a long-cherished dream to unite the Southern Slavs, was re-formed into a Communist whole after World War II. That’s despite the fact that its people had been at one another’s throats during World War II, due to deep religious and cultural differences. In Tito’s new, socialist Yugoslavia, the people were expected to live in “Brotherhood and Unity,” and nationalists who held on to past hatreds were punished with death or jail for their insubordinate grudges. Marriages between ethnicities were encouraged and celebrated, symbolic of a unified Yugoslavia. Nina herself is the product of a mixed marriage. But the policy of “Brotherhood and Unity” alone could not eradicate the pull toward nationalism. Many wanted to be independent from a greater Yugoslavia. Hence, the wars. The messy wars that sprouted up in varying degrees of intensity, from Slovenia, to Croatia, to Bosnia, to Kosovo.

As Maggie crouches near us with her camera, Nina starts to tell me about the war. She was ten years old, playing in a parking lot with neighborhood kids, when a grenade exploded.

“The boy in front of me died straightaway,” she tells me, and Nina felt something hot in her foot. “I looked down at my leg, and saw it was covered in blood.”

As she says this, I can’t help but look down Nina’s leg, skinny and veiny up close, to her foot, on which she now wears strappy high-heeled sandals, showing carefully pedicured toes and a faint scar. After seeing the blood on her leg, Nina fainted, and lay unconscious surrounded by dead, wounded, and crying children.

“When there’s an explosion, no one comes to help, because there’s always a second one coming,” she says.

Lucky for Nina, the second explosion missed them. The bomb, Nina tells me, was most probably set off by the Serbs.

“How do you feel about Serbs?” I ask, even though I know that Nina wouldn’t be here, at an ex-Yugoslavian event, if she hated Serbs. I’m asking the question for the benefit of the camera, because I know my audience of non-Yugos has no idea how our community works. I asked Nina the question to highlight a contradiction: not only do we not hate one another, but we actually love one another. And while there are nationalists out there (known for clashing at sporting events, or in nightclubs), those people are not here tonight. Nina, and most of the people at Joy nightclub this evening, are Yugo-nostalgics: they remember, and pine for, Yugoslavia as it was before the wars, before politicians and crazy people took over, when kids of all nationalities played in the parking lots without fear of death.

“Just because I was wounded by the Serbian side,” Nina says dutifully, glancing at the camera, “doesn’t mean I hate Serbs.”

She asks if I want to touch the shrapnel that is still lodged in her foot, and she guides my finger along the side until I feel a little lump, like a pebble under her skin. It moves around freely, and she says it hurts when the weather changes.

The other girls can hear our conversation, but continue doing their makeup. For most of us, war has always been present, if not in the foreground, then as a constant background noise, the details of mass graves, bombings, rigged elections buzzing like an old fridge, always there in the form of radio news, infiltrating our parents’ arguments. It’s not surprising to me that these women keep curling their eyelashes while Nina talks about being wounded. Or that the two of us can then get up from the floor, hug each other, and keep idly chatting without pause, turning a conversation from tragedy into something like breast tape, as we slip into our evening gowns, for part two of our evening of objectification.

Showtime. Nina is introduced to the audience again, now wearing a sparkly, cream-colored dress that plunges low between her breasts. This time, instead of walking offstage, she pauses by the microphone to answer questions. She waves at the crowd happily, like she was born to do this. “She’s good,” I whisper to the camera, falling into the on-the-ground-reporter style myself.

“What is your unfulfilled wish?” Monica asks, placing the microphone to Nina’s lips.

As if Monica isn’t there, Nina looks out at the crowd and says, in Bosnian, “For Yugoslavia to be like it once was.”

The cheer from the Yugo-nostalgics is so loud and long that Nina laughs, beaming out at the audience.

Waiting by the stage, I feel my eyes prick with tears, the fantasy of a Yugoslavia “like it once was” taking me to my happiest memories, of all of my family and friends in one place, before phone calls were long distance and expensive, before my parents became angrier at each other, before my dad got sick. Is the cheering crowd crafting Nina’s wish into their own fantasy, bringing back loved ones, making themselves un-foreign and loved, telling themselves: everything would be fine if only Yugoslavia was still around?

Monica the Aussie host cheers as well, as if the answer Nina gave makes complete sense to her, even if it was in a foreign language. Gushing at Nina in a way that suggests she’s partaken in some recreational drug use with members of the community, Monica asks: “And why do you think you should win the competition, and this ticket back home?”

“Because I’d like to see my family, which I haven’t seen for ten years,” Nina says, this time in her Bosnian-accented English.

Next up: Zora, her thick hair now up in a dark, elegant bun, answers the same question with her prepared answer: “Because I think I deserve to win, and I can win, and I think going overseas would give me the opportunity to appreciate not just what I have here, but what I left back at home.” Boom. Holding her head high, she spins around, strutting down the runway, and judging by the cheers, gathering a solid faction of supporters in her wake.

When it’s my turn, I feel grossly underqualified. I stand with my hands on my hips to stop the sweat from staining my expensive red evening gown. “Why do you think you should win?” Monica asks.

“Well, I believe I should win because I’ve never actually won anything.” I’d thought it was a good answer when I planned it (and it was true), but the crowd and Monica seem to be waiting for me to say something more to win hearts and minds, because there is silence. “Ever. Before.” The crowd starts to laugh and I shrug, starting my walk down the runway, forgetting that I’m supposed to stay and answer another question. I am now pretty much resigned to the fact that I’m not going to win this thing, though I send out an appreciative kiss to my mother, her clients, and the man with the cyst, all of whom continue to clap out of sympathy and nepotism, even though it’s painfully obvious I’m the losing horse in this race.

Back in the safety of our dressing room, we pose for a photo. In our beautiful gowns and our carefully made-up faces, we look like we’re dressed for prom. Except we don’t have dates. Like nuns are the brides of Christ, we are the brides of a dead Yugoslavia.

The evening gowns come off, and the bikinis come on, nervous energy spreading through the room. One of the Fantastic Face Beauty School students is using concealer and a tiny brush to cover the stretch marks on my thighs, while I, following the advice of my fellow contestants, slip rubbery inserts, called “chicken fillets” inside my bikini top, to make my breasts look bigger. During rehearsals, every now and then, a chicken fillet would become visible from the side, a rubbery mass trying to escape from under my armpit. I consider walking down the runway without moving my arms, to prevent the fillet from flying out into the audience and smacking a refugee in the face.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (April 16, 2019)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501165757

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"This stand-out memoir chronicles Stefanovic’s life from her childhood to early twenties, coming back and forth between Yugoslavia and Australia during the Yugoslav wars...Stefanovic’s story is as unique and wacky as it is important." —Esquire

“A poignant, charming, and gorgeously written account of the complexities of navigating the immigrant experience and finding a home — especially when the place you used to call home no longer exists as it once did… Fresh, vibrant, and enlightening, Miss Ex-Yugoslavia is a stunning immigrant narrative that will tug at your heartstrings the whole way through." —Bustle

“Smart, spirited….Full of lively anecdotes. Stefanovic tells her story of immigration and displacement, childhood pleasures and teenage angst.”

—Booklist (starred review)

"Sofija Stefanovic’s beautiful memoir Miss Ex-Yugoslavia depicts the elegant transit of a girl becoming an artist. This is a story we yearn to know: How does a girl lose her childhood, family, and nation, yet nurture her memories, dreams, and art? Stefanovic hits all her marks, and she keeps us in her thrall.”

—Min Jin Lee, author of Pachinko, a New York Times Bestseller and National Book Award Finalist

“Funny and tragic and beautiful in all the right places. I loved it.”

—Jenny Lawson, #1 New York Timesbestselling author of Let’s Pretend this Never Happened and Furiously Happy

“[A] brilliant debut memoir… Tongue planted firmly in cheek, Stefanovic’s memoir is equal parts raucous coming-of-age story, heartbreaking family drama, and quest for identity — topped with generous handfuls of political and historical introspection...Stefanovic is such a gifted, natural storyteller that all these elements blend together seamlessly, sometimes in the same paragraph, resulting in an authentic glimpse into a life filled with love and fear; hope and despair. It’s a marvel… Filled with Yugo-rock and news reports, Baby Sitters Club books and revolution, Miss Ex-Yugoslavia is a remarkable work from an exceptional storyteller." —The Cedar Rapids Gazette

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Miss Ex-Yugoslavia Trade Paperback 9781501165757

- Author Photo (jpg): Sofija Stefanovic Photograph © Michael Carr(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit