Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

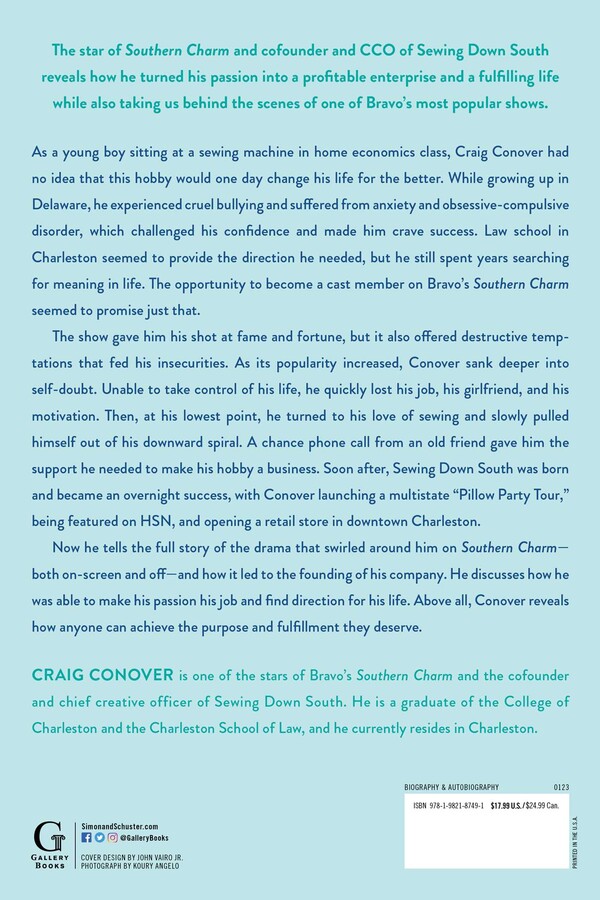

Perfect for fans of One Day You’ll Thank Me and Capital Gaines, the star of Southern Charm and cofounder and CMO of Sewing Down South reveals how he turned his passion for sewing into a profitable enterprise and a fulfilling life, while also taking us behind-the-scenes of one of Bravo’s most popular shows.

As a young boy sitting at a sewing machine in home economics class, Craig Conover had no idea that this hobby would one day change his life for the better. Growing up in Delaware, Conover experienced cruel bullying and suffered from severe anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. But while law school in Charleston seemed to provide the direction he needed, Conover spent years searching for meaning and passion in life. The chance to become a cast member on Bravo’s Southern Charm promised to provide that.

Though the show gave Conover a shot at fame and fortune, it also offered destructive temptations that fed his insecurities. As the show increased in popularity, he sank deeper into self-doubt. Unable to take control of his life, Conover quickly lost his job, his girlfriend, and his motivation. Then, at his lowest point, Conover turned to his passion—sewing—and slowly pulled himself out of the spiral. A chance phone call from an old friend gave Conover the support he needed to turn his hobby into a business. Soon after, Sewing Down South was born and became an overnight success, with Conover launching a multi-state “Pillow Party Tour,” being featured on HSN, and opening a retail store in downtown Charleston.

Now, Conover reveals the full story of the drama that swirled around him on the show—both on screen and off—and how it led to the founding of Sewing Down South. He also talks about how he was able to turn his passion into his work and reclaim the direction of his life and what lessons we can learn from his experience.

As a young boy sitting at a sewing machine in home economics class, Craig Conover had no idea that this hobby would one day change his life for the better. Growing up in Delaware, Conover experienced cruel bullying and suffered from severe anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. But while law school in Charleston seemed to provide the direction he needed, Conover spent years searching for meaning and passion in life. The chance to become a cast member on Bravo’s Southern Charm promised to provide that.

Though the show gave Conover a shot at fame and fortune, it also offered destructive temptations that fed his insecurities. As the show increased in popularity, he sank deeper into self-doubt. Unable to take control of his life, Conover quickly lost his job, his girlfriend, and his motivation. Then, at his lowest point, Conover turned to his passion—sewing—and slowly pulled himself out of the spiral. A chance phone call from an old friend gave Conover the support he needed to turn his hobby into a business. Soon after, Sewing Down South was born and became an overnight success, with Conover launching a multi-state “Pillow Party Tour,” being featured on HSN, and opening a retail store in downtown Charleston.

Now, Conover reveals the full story of the drama that swirled around him on the show—both on screen and off—and how it led to the founding of Sewing Down South. He also talks about how he was able to turn his passion into his work and reclaim the direction of his life and what lessons we can learn from his experience.

Excerpt

Chapter 1: A Boy from Delaware 1 A BOY FROM DELAWARE

In the second season of Southern Charm, I brought my friends Shepard Rose and Whitney Sudler-Smith to my home in Ocean View, Delaware. We played golf, they met my parents, and during dinner one evening, Whitney told my mom and dad that he was worried about me.

“He’s wasting his talents, staying up and partying all night,” said Whitney. “He goes out every night. How do we give him a kick to get his life in order?”

I was horrified. I managed to keep it together in front of my parents, but the next morning on the links, I let Whitney have it. I was furious that he would reveal these things to my parents, especially after I asked him not to.

“It’s out of concern and love, man,” replied Whitney. “You’re a bit of a mess right now.”

He wasn’t wrong. I was falling deeper into the “Neverland” world of Charleston, living like a celebrity, and losing any drive I once had. I’d recently been fired from my job as a law clerk for repeatedly coming in late. Hell, I hadn’t even graduated from law school because I was still shy one credit—though no one, not even my family, knew that yet. And I blurted it all out in a moment of frustration and clarity.

“Every day I’m stressed out as fuck,” I finally said to them. “My rent’s fucking sky-high. I’m spending too much money. Half the time I’m embarrassed to tell you guys because I don’t want you to look down on me. You guys are doing great right now. I’m running away from the truth. This is the first time I’m admitting to myself out loud that, yeah, something needs to change because shit’s not going right right now.”

It would be some time still before I used these words to change myself. I had a long journey ahead of me… and it would get much worse before it started to get better. But while I could at least admit that something was wrong with the direction of my life, that’s not why I had exploded at Whitney.

I wasn’t pissed because what he said was inaccurate; I was pissed because there was no good reason why I was failing and miserable. Maybe I had just been a spoiled brat as a kid, indulged by indifferent parents. Maybe I had always been kind of a failure, struggling through grade school and always the last picked for sports. Maybe I just hadn’t ever been taught hard work or discipline, coasting through childhood without consequences.

Whitney and Shep didn’t see that. Instead, they saw my bedroom with my many awards and trophies, both athletic and academic. They saw my parents, tender and good-hearted, whose love and devotion to their children was just as strong that day as it had been when my brother and I were first born. In just twenty-four hours, they had caught a glimpse of the boy I had been, surrounded with love and gifted with so many of the blessings that really mattered in life: family, values, intelligence, and a sense of responsibility.

What happened to this boy? Why did he grow up to be this wayward and lost young man they knew in Charleston? There was no reason, no evidence, that explained the difference between man and child. I had been given every opportunity to realize my potential, and yet I was wasting them all. Why?

It wasn’t a question I was prepared to answer at that moment, but I also wasn’t that interested (yet) in answering it. My little outburst on the golf course was real, if also a bit disingenuous. I believed all these things; I just wasn’t ready to fix any of it.

At the time, I was upset because I didn’t want my parents to worry. I had tried very hard to keep the truth of what was happening in my life concealed from them. I would straighten myself out, I just needed time.

Looking back, I can admit that I was just terrified of my own shame. In fact, I was riddled with shame—and guilt. All the things that Whitney saw in Ocean View, I saw too. I saw the enormous love of my parents and the sacrifices they had made for my brother and me. I saw the accolades and awards that seemed to foreshadow success. I saw the comfort and safety of a home that encouraged me to dream big and reach my potential. I saw the person I was supposed to be. And every day I looked in the mirror at the person I had become. To avoid seeing that person, to save my ego from the debilitating guilt, I had learned ways to hide from myself. I became very good at it, to be honest. But those methods—the partying, the drinking, the staying out late—were also what intensified the guilt in those terrible moments of clarity.

Going home to Delaware forced me to stare at that boy in the mirror. The boy who had been given everything he needed to succeed and realize his dreams. I had left my home in Ocean View to conquer the world on my terms. I had returned exhausted and broke.

So who was that boy? Where did he come from, and how did he grow up?

LOWER, SLOWER DELAWARE

When I was two years old I started talking, and, as my mother, Marty, says, I never stopped. The polite term would be “precocious,” although I believe it’s more accurate to say that I was a talkative know-it-all. This isn’t unique to me. The gift of gab was handed down to me from my father, Craig, just one in a long line of Conovers who say what’s on their mind—often. By the time I reached school, my hand was up constantly, always ready with an answer, correct or not. One of my elementary school teachers one day mentioned to my mother, who was by then also a teacher, that she was pretty sure little Craig knew more than she did. Growing up Catholic, I went to church every Sunday, but being a Conover, I questioned everything I was told, to the consternation of my religious mother and the approval of my skeptical father. In fact, as the years passed, and Christopher and I grew up, it became clear that he had inherited most of the traits of my mother—reserved, disciplined, and serious. Whereas I am more like my dad—outgoing, restless, ambitious, but also cursed with procrastination.

My father started out in the restoration business before he and my mother married. He was the one going on the calls, cleaning the houses and buildings after a flood or other catastrophe, and I think he enjoyed being away from a desk. When they got engaged, my father got an office job, ordering parts and whatnot. By this time, they had moved closer to the beach and my father hated every minute of being stuck behind that desk. “It wasn’t me,” he once said. (It’s not me either, Dad.) Within one week, he’d quit that job and started his own carpet-cleaning company with a few friends. Four months later, the money had run out and one of the partners had left. But my dad stuck with it, and after he and Mom married a few months later, he was able to pay back the investment money, leaving him the sole proprietor of the business. My mother would eventually become an elementary school teacher, but at this time, before I was born, she worked with my father full-time on the company. Those first five years, as they now tell it, were tough, and keeping both themselves and the company above water was a constant struggle.

On February 9, 1988, two years into the business, I was born. Although money was tight, I never experienced want or deprivation. My parents made enough to pay the mortgage and provide my brother and me with what we needed, but there was little left over for any type of luxury or extravagance. I didn’t notice—except when I wanted a gumball from the machine at the grocery store. My future drive to make money had everything to do with my own ambition and almost nothing to do with any painful childhood memories of going without heat or other necessities. As a child, I distinctly remember going with my father on emergency cleaning calls, which I loved. It wasn’t the work I enjoyed—I have always hated manual labor—it was being with my dad and feeling like I was an important part of his life. My father eventually grew the business to the point where my mom could start working as a teacher, and the business continues to thrive thirty years later, with Christopher now running the operations.

Meanwhile, my own early childhood was happy. I excelled at school and sports, and quickly grew to love the world in which I lived. My parents eventually bought a second house in Fenwick, closer to the beach, and I spent my summer vacations in those waters, learning to surf and appreciate the quieter life in “lower, slower Delaware,” as we call this little corner of this little state. I took to this lifestyle, and for this reason, I never encountered any kind of “culture shock” when I eventually left for Charleston. As southern cities go, Charleston is pretty damn cosmopolitan, but there remain vestiges of the old southern way of life that can sometimes annoy transplanted Yankees. I never experienced this—or, if I did, I was drawn to it as a reminder of home.

And home was and remains my place of comfort. Both my parents worked very hard, but they always had time for my brother and me. They never missed a soccer game, a baseball game, or a wrestling match. They never were too busy to help with homework. They always listened to our worries and troubles, and they didn’t act as if our childhood dramas were unimportant. Every night we would have dinner together, no matter what. It was our time together as a family, sharing stories of our day and working together as a single unit. These family dinners were so much a part of my upbringing that I just assumed that’s how everyone lived. It wasn’t until I was off on my own at college and later that I came to realize how precious and important those times around the table truly were. No, not everyone grew up like that. No, not everyone had a mom or dad who was around to listen to them, to enjoy their company, to build and grow a family into the strongest bond a person can have. There’s a reason why in later years, when the weight of my struggles bore down on me, that I often retreated to the comfort of home, to the relaxing and restorative presence of my family around the dinner table.

All of which is to say that of the many blessings I have had in life, none stand out as strongly as the life my parents provided to me growing up. I know that traumatic events that happen in childhood can often lead to severe internal problems in later years, but I can’t point to anything like that from my own early years. There was a time when, in the third grade, my aunt on my father’s side was killed in Baltimore. It was the first time I ever saw my father cry—a moment that stays with a child forever. It’s the moment when you first glimpse your parents, especially your father, as an actual person and not a marble icon. Some years later, when I was a sophomore in high school, my dad underwent heart surgery, and his recovery lasted several months. My father’s stay in the hospital had a profound effect on my future. At the time, I had very vague notions of becoming a doctor, but this was based on little more than trying to tie my academic performance to a successful profession. I had no real medical passion, a fact made painfully obvious when I visited my father in the hospital after his surgery. I never made it to his room in the ICU. There was something deeply unsettling to me about being in the hospital, and I found myself running outside before ever seeing him. So that knocked “doctor” off my list of possible careers.

A non-drinker, my father hated taking his pain medication, which made for a very sour patient that the rest of the family just had to deal with. Because I took over a lot of his home care, he directed much of his externalized anger and frustration toward me. Being older and aware of the reason, I took it in stride. But aside from these moments, which hardly rise to the level of traumatic memories, my childhood growing up in Ocean View, spending summers in Fenwick and Bethany Beach, was about as idyllic as a middle-class kid could ever want.

A NEW PASSION AND DEEP SCARS

What this safety and comfort instilled in me was self-confidence from a young age. I pursued my interests and hobbies without the typical adolescent worrying of what others might think. For the most part, these interests were your basic American boy interests, especially athletics. I loved all the sports that are popular on the East Coast, including soccer, lacrosse, and baseball, and I was good at them. Though skinny, I wasn’t yet at the level where my size worked against me, so I couldn’t even be self-conscious about that yet. But I also wasn’t that typical. When I’d come home from practice, I would turn on Emeril Lagasse and help my mother make dinner. My mom was a full-time schoolteacher by then, and she was more than happy to have a little help in the kitchen. For me, though, I genuinely enjoyed it. I even started to put together my own cookbook full of my favorite recipes. I suppose I was aware that this wasn’t what most boys my age did when they got home from school, but I didn’t care. Never much of a video-gamer, I simply loved to cook.

I started to recognize that I had an appreciation for the more domestic hobbies usually associated with girls, especially when I first learned to sew. Neither of my parents were particularly adept or interested in it, as far as I can remember. I first came across sewing in the seventh grade, in Mrs. Hurley’s home economics class. The classroom was divided into two sections, one half dedicated to the kitchen and cooking, the other to sewing, with several electronic sewing stations set up. As is typical for that age, most of the boys laughed their way through class, while most of the girls enjoyed it. I was with the girls. While I do think it’s true that these interests roughly break down by gender, I think far more of the boys enjoyed it than they were willing to admit. If it wasn’t sports, then they weren’t allowed to enjoy it. But I did, and I had no problem showing that I did. I remember making my first pillow in Mrs. Hurley’s class and feeling a sense of tremendous satisfaction at having created something. Using my hands, I had turned what had been some fabric and thread into something real and beautiful (to me, at least). I didn’t realize it at the time, but I had stumbled upon something that had given me joy. It was an amazing feeling, similar to what I felt when I sat down to a dinner I had helped prepare. I was too young to realize how precious that feeling really is, and perhaps for this reason I abandoned these hobbies as I got older. It wasn’t because I would grow self-conscious about these interests; rather, because my childhood was full of joy, I never expected to find myself in a place where I would need joy to get me through dark moments.

And those moments would strike soon enough. As a child and adolescent, I rarely experienced true cruelty. There was the typical teasing that boys and brothers inflict on one another, but nothing that rose to the level of outright viciousness. But if my childhood could be divided in half, much like Mrs. Hurley’s classroom, one half, the earlier half, was full of sunlight, happiness, and love. I had nothing to fear and had been able to develop my abilities and interests free of any outside interference. This would come to a swift end when I reached high school.

There’s no need to recount all the episodes of bullying that happened to me as a teenager. The best way to describe it is that it was just this persistent state of being for me, something that I had to deal with every day. Most of it originated with the older players on the school soccer team. Why did they target me? I was small and skinny, so I suppose that had something to do with it. I also believe that the self-confidence I had acquired and built throughout adolescence made me a target too. Bullies hate seeing what they lack in others, and their efforts are, above all, an attempt to make the target feel as bad as they do. In that, they were successful. I lost much of my confidence because of what they put me through, and I started to become painfully aware of my own inadequacies, to the point that they were all I focused on. I still carry these scars with me today. I developed a need to be liked by everyone, accepted as an equal. If I wasn’t good at something—or if I outright couldn’t do something—I chose to hide it rather than accept it. I just couldn’t bear the idea of anyone having a lesser opinion of me.

One particular moment stands out as emblematic of the bullying. I was a freshman on the junior varsity team, which shared a bus with the varsity players. I got off the bus one day and realized I had left behind my bookbag. The next day I retrieved my bag and reached in to take out one of the books for my English class. It was a thick, heavy book. Well, the older kids had used a whole roll of athletic tape on it, which I had to tear away. And when I finally got the book open, I realized that they had also smashed Doritos between the pages, leaving an oily residue that completely ruined the book, which I had to pay for. To some, it might seem that it’s just a book, so what? But I was a good, serious student. I appreciated my books and considered them valuable beyond their monetary price. For those players to deliberately destroy my book affected me deeply. To this day, I don’t understand that level of mindless cruelty. What didn’t they like about me? What had I done wrong?

With the benefit of hindsight, I sometimes look back on this episode and others like it and wonder if it was really that bad. But then I quickly remember that this was the same thing I had told myself back then. I wasn’t getting beaten up; I was just the mark for this group’s senseless viciousness. I wasn’t afraid for my safety or my life, but I was made to feel like there was a problem with me. Maybe it was my stature. Maybe it was my teeth, which weren’t the best before I got braces and whitened them. Maybe it was because I was a little geeky. Whatever it was, their purpose was to make me feel like garbage. And, like I said, they succeeded. I internalized their bullying to the point where I felt that something was wrong with me if they didn’t like me. This obsession with what others thought about me—by no means abnormal for a teenager—made me turn from a confident kid into someone who sought validation from others. I couldn’t be happy with myself unless others were happy with me. This was the bullies’ deepest cut, and the one that left a lasting mark. At the same time, I knew that one day I would prove them all wrong. I didn’t know how then, but their cruelty was motivation for me then and later.

Despite the prevalence of the bullying, I never got used to it. Some days were better than others, when the bullies simply forgot to make me a target, but that only led to agonizing uncertainty and paranoia. When I’d leave for school in the morning, I girded myself for what might happen. If I was bullied, then I had to deal with it. If I didn’t get bullied, then I was left with this pent-up anxiety that started to affect other aspects of my life. It was during these years when I developed some obsessive-compulsive tendencies. I don’t think I can attribute all of it to the bullying, since OCD definitely runs in my family, but like many mental health conditions, my OCD needed a trigger—and bullying was the trigger. For instance, my bedtime routine started to take forty-five minutes, because I had to look under my bed three times; I had to check the closet; I had to shut the doors just right; I had to turn off the lights just right; and I had to brush my teeth in a certain way that made me gag. In the mornings, I would repeat this process, and sometimes throw up my breakfast.

One day I had to serve an in-school suspension for an incident that was a result of the bullying. Before school, I had already thrown up my breakfast because of my OCD, and so went to serve the suspension on an empty stomach. For lunch, the school served only cheese sandwiches, which I couldn’t eat. Don’t ask me why. The single-slice Kraft cheese makes me nauseous. So I went without lunch that day. After the suspension, I had a wrestling match that just so happened to be against one of my main antagonists. I had never lost to this kid. In fact, I was undefeated. Everyone expected me to win—including myself. Except I hadn’t eaten anything all day and had no strength going into the match. I lost. On the way home that evening, my father could tell that something other than losing was bothering me, and I finally broke down. With tears running down my face, I explained why I had lost; I explained what had been going on at school; I explained why it took me forty-five minutes to get to bed each night, and why I left for school hungry that morning.

This was the first time I had ever tried to explain the impact of the bullying to my parents. There was so much shame that came with it, like I had let my parents down for becoming the bullies’ target. Again, this is the effect of the bullying itself, since it suggested I wasn’t strong enough to handle a little teasing. I don’t think that way anymore, and I remember feeling tremendously better after telling my father all the things I kept hidden from him. The reason I had not said anything before then was because I didn’t want to worry them. Listening to me spill my guts, my father understood the dilemma. He knew that, as a teenager, I wouldn’t want Dad and Mom coming to save me. But he also made it clear to me that he was always there to support me and help me through difficult moments in my life, no matter what. It was an offer that I would accept more than once in the years that followed. Still, it wouldn’t be until I started talking about the bullying on television that my mother finally understood the extent of it. I know it crushed her to hear how badly those years affected me, and that she blames herself for not seeing it at the time.

Eventually, as those older kids graduated, the bullying slowed and then stopped altogether. I went on living my life, playing sports, getting good grades, and otherwise enjoying my high school years. By the time I graduated, I felt like those years were behind me, that I had survived them, and I wouldn’t have to worry about the bullies ever again. I was right in some ways, but terribly wrong in others. The bullying might have stopped, but the scars would stay with me for many years.

A BUSINESS CHAMPION—KIND OF

I don’t want to leave the impression that my high school years were defined only by bullying. There were some pretty remarkable moments too, not just in sports but also in my academic pursuits. In particular, and quite relevant to this book, I was a member of the Business Professionals of America, which seeks to empower students with business and leadership skills. Several friends and I were members of BPA, and as juniors we had competed at the state championship in the category of small-business management. Much to our own surprise, we won the state tournament and had a chance to compete in the national competition at Disney World in Orlando.

There was a bit of a “David vs. Goliath” atmosphere to the national tournament, which was dominated by far wealthier private school teams. The other teams all showed up in matching uniforms; we were dressed in our plain clothes, just four public school kids from Indian River High School. Our feeling was that we were just along for the ride, happy to be there and enjoy a mini vacation at Disney. We didn’t go expecting much, and so wouldn’t have been terribly disappointed if we left with nothing. In fact, as we presented our business solution to the judges—it was based on revamping an ice-cream shop—they stopped us repeatedly and challenged several of our assertions. We all got the sense that the judges were trying to intimidate us, although I won’t go so far as to say that it was because we were public school kids from lower Delaware. I just think the judges felt we wouldn’t be as prepared as some of the more serious teams. But we didn’t back down. Two of our team members, Chad and Tom, had even worked at an ice-cream shop in Bethany Beach during the summer. That didn’t necessarily make them ice-cream professionals, but it certainly gave them far greater insight into the business than these judges had. The back-and-forth got quite heated, to the point that when we left the room, we felt that that either we had just earned the tournament win… or last place.

The next day was awards time, and we filed into a huge auditorium with five thousand other people. The organizers ran through each category, inviting each of the finalists onstage before announcing the winner in that group. When they got to the small business category and started calling up the top ten finalists one by one, the speaker announced, “Indian River High School,” and the four of us started smiling. We walked toward the stage amid the glares of the other teams who were furious that this ragtag group of public school kids had bested them. Onstage, looking out at this sea of people, the judges said they’d announce the top three, leaving the winner for the last. Third and second place were announced, and we all looked at one another. Holy shit, we’d won! So when the speaker once more said, “Indian River High School,” we just started laughing. Perhaps the best moment of that day was seeing our advisor, Mr. Murray, jumping up and down in his seat as the spotlight came to rest on his winning team.

Now, I don’t mean to suggest that our crushing victory at the BPA Nationals foretold any future business success. It’s not like I saw my career path as an entrepreneur or anything. But I’ve always been struck by how four kids with a little bit of street smarts were able to take down teams that were steeped in theory and formal business education. (The looks on their faces were pretty priceless.) I’m reminded of that triumph every now and then when debating future decisions for Sewing Down South. Sometimes all the education in the world simply exists to tell you why your idea is a bad one. You’ve learned enough to know that you don’t know anything, and you become paralyzed or guided by fear. You don’t pursue the chances you should because all the business books tell you they won’t work.

Well, sometimes they do work. Sometimes listening to your gut and going off your own experience is the right path forward.

COLLEGE AND CHARLESTON

By the time I was old enough to start thinking about college, I only knew this much: I was ready to leave home. I didn’t know where yet. I just knew that my path was beyond the confines of Delaware. I wasn’t running away, either. Yes, the bullying had left a deep and lasting impression on me, but it wasn’t the reason I wanted to leave home. It was more like I was running toward something. I felt I had done all that I could in this little corner of the world and that it was time for a fresh start (and independence) elsewhere. I guess you could say that I had the same feeling the early American settlers had had when they looked out across the expansive West. There I would find my fortune.

I applied to several colleges but had no strong feelings about any of them. That’s when my friend Sean told me about the College of Charleston. It wasn’t like Charleston was any sort of destination for me. I didn’t have thoughts about the city one way or the other. But then I went down for a visit. I realized, Yes, this is where I’m going to go to school. I was close to my beloved Atlantic Ocean; I was in a culture and a lifestyle that wasn’t frenzied or manic. (The sight of the southern women didn’t hurt either.) And while there was a feeling of familiarity with Charleston, coming from “lower, slower Delaware,” there was also a vibrancy that excited me. The city was in the middle of a cultural renaissance, with the Old South—and birthplace of the Confederacy—giving way to this younger, more socially aware wave of outsiders. In other words, Charleston had become a destination for those who appreciated the city’s beauty and wanted to help it move beyond its more traditional roots. There was also a pretty kick-ass partying scene that certainly impressed a kid like me.

In trying to place my college years in the narrative of this book, there are two points that stand out. The first was coming to some understanding of what I wanted to do with my life. I had mentioned the idea of being a doctor earlier—only to learn that hospitals were horrible places for me. I had left behind any notion of pursuing sewing or the other domestic crafts that I had fallen in love with as a child. Those were personal interests, but hardly career-worthy pursuits, or so I thought. I was smart, but I had no firm direction toward a specific intellectual passion. Looking back now, I regret that I wasn’t introduced to the field of engineering at an early age. The mathematics and the science inherent in engineering were two fields I had always excelled in, and was even passionate about. But I came to this realization too late in life, certainly if one wanted to be an engineer, whose career path begins freshman year in college.

But then there was the law.

On Southern Charm, viewers were right to question my commitment to the law, especially in those earlier seasons. Lawyers must necessarily be hardworking, disciplined professionals—the very qualities I lacked in my mid-twenties. I can laugh at the joke now, even if I want to correct the record a bit. I did fall in love with the law in college. There were a couple moments that are worth mentioning. The first is that during my junior year I was arrested for public intoxication. It was, in fact, a case of mistaken identity (they later caught the real culprit), but it left a lasting impression on me. My father called a friend of his who was an attorney to ask for his advice. After hearing my story, he decided to represent me in court and got the charges dismissed. The whole process fascinated me, not least because I felt like I had been wronged by the system. Being punished for something I didn’t do opened my eyes to the harsh reality of the judicial system. Yes, it often works as it’s supposed to, but it also sometimes doesn’t. And to say that no system is perfect doesn’t do much for those wrongly accused or convicted. Even as a child, and especially as an adolescent or teenager, injustice affected me deeply. I still remember being on that soccer bus when the bullies had turned their sights on another kid, and sticking up for him. I knew what it would (and did) lead to, but I can’t stand watching others suffer unjustly at the hands of bullies.

This growing passion and fascination with the law was also spurred by a course I took on federal courts in my junior year, taught by a federal magistrate. My eyes were opened to the inner workings of a system whose roots stretch back centuries. And the ones who have knowledge of this fascinating system, and know how to navigate it, are lawyers. Their job is to seek justice—and put down the bullies. I was in.

That’s the righteous part of my decision to go to law school. There remains a more banal and unflattering one. Law school seemed like a surefire way to become wealthy and successful. I didn’t have a driving need to make money because of the circumstances of my upbringing, although my brother’s and my love of good food and travel continually perplexes my parents, who rarely experienced either. I wanted to make money because I wanted to “make it.” I wanted to feel successful by having all the trappings of success. I also saw the law as a way to achieve financial freedom, to live the way I wanted to, and even to give back if I could. I felt like becoming a lawyer would prove to all the bullies back home that I had succeeded, despite their best attempts. My revenge was my success. While this isn’t the best reason to go to law school, I also don’t think I’m unique in having less-than-savory motives for choosing a profession like the law. But I will admit that I was very much responding to the scars that the bullying had left on me.

Besides, for a procrastinator like me, law school offered a structured path forward. I could delay my entry into the real world another three years and come out of it with a six-figure associate’s salary. Yeah, I was definitely in.

THE BEGINNINGS OF ADDICTION

The other point I should make about my college years is that this is when I first started taking Adderall, and that’s because my procrastination didn’t start to become a problem until I went to college. Then it became a big problem. In high school, I was sheltered by the structure of my family life. When one was home on a school night, there wasn’t much else to do other than schoolwork. That structure disappeared in college, and I often found myself overwhelmed by the plethora of distractions. There was always something else I could be doing besides studying. I went from getting As in high school to getting four Ds one semester during my sophomore year in college. It was toward the end of my first semester junior year that my roommate gave me an Adderall, telling me it would help me study. I had never taken a pill like that before. But, damn, did the little thing work. It was like a light went off in my brain that said, “THIS is what we’ve needed all along!” By the end of my junior year, I was taking business administration and finance classes, which I loved, and got on the Dean’s List with a 3.8 GPA. Not surprisingly, I gave all the credit to my new friend.

Which isn’t to say that I spent all my time in the library. I did go to the library, where I would pop a pill and study for several hours. But Adderall keeps going even if you’ve finished the task you took it for in the first place. So, whether it was nine o’clock at night or one in the morning, I’d go from the library to a bar or a party. I had grown into myself while at college, and the girls had noticed. I had always been shy, but I learned that I transformed into this new charismatic person after just a few drinks. I quickly became very acquainted with the Charleston social scene, befriending all the bartenders and club owners, who often extended invitations to my friends and me to exclusive openings because they knew we’d bring the girls. I stopped being an outsider and carved out my own place in this young, vibrant town. Everywhere I went, I knew someone, whether they were a student or a local. One of the students a few years ahead of me, Jerry Casselano, bounced at a favorite bar of mine and would let me in even though I wasn’t twenty-one. Jerry would remember me years later when he was running his own sports marketing firm, and he would make a call that would change both our lives.

Adderall helped me study, but it didn’t solve my procrastination. For instance, I realized quite quickly—and this would become a major problem in law school—that I could avoid doing most of the work during the semester if I pulled some all-nighters at the end. For most people, this is an unsustainable behavior, but with Adderall, I could do it. I could study all night, night after night. While I still wasn’t taking the drug recreationally—by which I mean, for partying—I started to use it whenever I needed to accomplish anything. Suddenly, I found reasons to drive home to Delaware, instead of fly, because Adderall made the trip fun. The little pill would focus my mind in a way that felt superhuman.

I eventually approached my parents about it, since I wanted them to know I was doing something about my academic decline. Taking it without their knowledge had felt shady, and I hated that feeling. And to be honest, Adderall is a bit of a truth serum. Once I started talking, I just kept going. I was still nervous to tell them, for all the reasons I was nervous to tell them anything, because I thought they would worry. Both my parents had stopped drinking when I was born, and to this day they remain absolutely sober. Taking a pill, even one that has appropriate medical uses, seemed like something they’d be against. Except my mother wasn’t. “Oh, Craig, I’ve known you should have been on something since grade school, you just never needed it,” she said when I spilled. As a schoolteacher, my mother was well aware of ADHD, and she had long suspected that I suffered from it. She wasn’t wrong. My father was supportive, too, but he also saw the early stages of what was to become an addiction. When I was home from school, I’d typically wait to pack until the very last moment, then I’d stay up all night packing. These are behaviors that parents catch on to. So while they were supportive of me getting a prescription to combat my ADHD, even then my father was aware that I wasn’t always taking it for the right reasons.

“I KNOW JUST THE GUYS”

Still, it would be some years before I started to really abuse Adderall. I had come to rely on it more and more, but I also attributed all my later academic success to it. How could something so helpful to me be bad for me? In any case, with my grades greatly improved, I was accepted into the Charleston School of Law, with a partial scholarship, which I entered a year after graduation. I was excited. I was also confident. College had given me a much-needed dose of validation that seemed to sweep away the nightmares from my high school days. I was no longer just a geeky kid. I was still skinny, but I had also grown into my body. I had made lifelong friends and had become popular, not just in college but in the city itself. People knew me, and I was treated like a local at bars and restaurants. Charleston had become my home. And I had no intention of leaving. Three more years of nothing but school seemed about right.

It was during my first year in law school that I received a Facebook message from a friend, a girl named Lane. She was a local, a true Charleston girl who I knew from the bar scene. She said she was working with a television producer, a guy named Whitney Sudler-Smith, who was in town to cast a new reality TV show. Whitney had asked her if she knew any young guys who were fun, charismatic, and keyed into Charleston’s social life.

“I know just the guys,” she replied.

In the second season of Southern Charm, I brought my friends Shepard Rose and Whitney Sudler-Smith to my home in Ocean View, Delaware. We played golf, they met my parents, and during dinner one evening, Whitney told my mom and dad that he was worried about me.

“He’s wasting his talents, staying up and partying all night,” said Whitney. “He goes out every night. How do we give him a kick to get his life in order?”

I was horrified. I managed to keep it together in front of my parents, but the next morning on the links, I let Whitney have it. I was furious that he would reveal these things to my parents, especially after I asked him not to.

“It’s out of concern and love, man,” replied Whitney. “You’re a bit of a mess right now.”

He wasn’t wrong. I was falling deeper into the “Neverland” world of Charleston, living like a celebrity, and losing any drive I once had. I’d recently been fired from my job as a law clerk for repeatedly coming in late. Hell, I hadn’t even graduated from law school because I was still shy one credit—though no one, not even my family, knew that yet. And I blurted it all out in a moment of frustration and clarity.

“Every day I’m stressed out as fuck,” I finally said to them. “My rent’s fucking sky-high. I’m spending too much money. Half the time I’m embarrassed to tell you guys because I don’t want you to look down on me. You guys are doing great right now. I’m running away from the truth. This is the first time I’m admitting to myself out loud that, yeah, something needs to change because shit’s not going right right now.”

It would be some time still before I used these words to change myself. I had a long journey ahead of me… and it would get much worse before it started to get better. But while I could at least admit that something was wrong with the direction of my life, that’s not why I had exploded at Whitney.

I wasn’t pissed because what he said was inaccurate; I was pissed because there was no good reason why I was failing and miserable. Maybe I had just been a spoiled brat as a kid, indulged by indifferent parents. Maybe I had always been kind of a failure, struggling through grade school and always the last picked for sports. Maybe I just hadn’t ever been taught hard work or discipline, coasting through childhood without consequences.

Whitney and Shep didn’t see that. Instead, they saw my bedroom with my many awards and trophies, both athletic and academic. They saw my parents, tender and good-hearted, whose love and devotion to their children was just as strong that day as it had been when my brother and I were first born. In just twenty-four hours, they had caught a glimpse of the boy I had been, surrounded with love and gifted with so many of the blessings that really mattered in life: family, values, intelligence, and a sense of responsibility.

What happened to this boy? Why did he grow up to be this wayward and lost young man they knew in Charleston? There was no reason, no evidence, that explained the difference between man and child. I had been given every opportunity to realize my potential, and yet I was wasting them all. Why?

It wasn’t a question I was prepared to answer at that moment, but I also wasn’t that interested (yet) in answering it. My little outburst on the golf course was real, if also a bit disingenuous. I believed all these things; I just wasn’t ready to fix any of it.

At the time, I was upset because I didn’t want my parents to worry. I had tried very hard to keep the truth of what was happening in my life concealed from them. I would straighten myself out, I just needed time.

Looking back, I can admit that I was just terrified of my own shame. In fact, I was riddled with shame—and guilt. All the things that Whitney saw in Ocean View, I saw too. I saw the enormous love of my parents and the sacrifices they had made for my brother and me. I saw the accolades and awards that seemed to foreshadow success. I saw the comfort and safety of a home that encouraged me to dream big and reach my potential. I saw the person I was supposed to be. And every day I looked in the mirror at the person I had become. To avoid seeing that person, to save my ego from the debilitating guilt, I had learned ways to hide from myself. I became very good at it, to be honest. But those methods—the partying, the drinking, the staying out late—were also what intensified the guilt in those terrible moments of clarity.

Going home to Delaware forced me to stare at that boy in the mirror. The boy who had been given everything he needed to succeed and realize his dreams. I had left my home in Ocean View to conquer the world on my terms. I had returned exhausted and broke.

So who was that boy? Where did he come from, and how did he grow up?

LOWER, SLOWER DELAWARE

When I was two years old I started talking, and, as my mother, Marty, says, I never stopped. The polite term would be “precocious,” although I believe it’s more accurate to say that I was a talkative know-it-all. This isn’t unique to me. The gift of gab was handed down to me from my father, Craig, just one in a long line of Conovers who say what’s on their mind—often. By the time I reached school, my hand was up constantly, always ready with an answer, correct or not. One of my elementary school teachers one day mentioned to my mother, who was by then also a teacher, that she was pretty sure little Craig knew more than she did. Growing up Catholic, I went to church every Sunday, but being a Conover, I questioned everything I was told, to the consternation of my religious mother and the approval of my skeptical father. In fact, as the years passed, and Christopher and I grew up, it became clear that he had inherited most of the traits of my mother—reserved, disciplined, and serious. Whereas I am more like my dad—outgoing, restless, ambitious, but also cursed with procrastination.

My father started out in the restoration business before he and my mother married. He was the one going on the calls, cleaning the houses and buildings after a flood or other catastrophe, and I think he enjoyed being away from a desk. When they got engaged, my father got an office job, ordering parts and whatnot. By this time, they had moved closer to the beach and my father hated every minute of being stuck behind that desk. “It wasn’t me,” he once said. (It’s not me either, Dad.) Within one week, he’d quit that job and started his own carpet-cleaning company with a few friends. Four months later, the money had run out and one of the partners had left. But my dad stuck with it, and after he and Mom married a few months later, he was able to pay back the investment money, leaving him the sole proprietor of the business. My mother would eventually become an elementary school teacher, but at this time, before I was born, she worked with my father full-time on the company. Those first five years, as they now tell it, were tough, and keeping both themselves and the company above water was a constant struggle.

On February 9, 1988, two years into the business, I was born. Although money was tight, I never experienced want or deprivation. My parents made enough to pay the mortgage and provide my brother and me with what we needed, but there was little left over for any type of luxury or extravagance. I didn’t notice—except when I wanted a gumball from the machine at the grocery store. My future drive to make money had everything to do with my own ambition and almost nothing to do with any painful childhood memories of going without heat or other necessities. As a child, I distinctly remember going with my father on emergency cleaning calls, which I loved. It wasn’t the work I enjoyed—I have always hated manual labor—it was being with my dad and feeling like I was an important part of his life. My father eventually grew the business to the point where my mom could start working as a teacher, and the business continues to thrive thirty years later, with Christopher now running the operations.

Meanwhile, my own early childhood was happy. I excelled at school and sports, and quickly grew to love the world in which I lived. My parents eventually bought a second house in Fenwick, closer to the beach, and I spent my summer vacations in those waters, learning to surf and appreciate the quieter life in “lower, slower Delaware,” as we call this little corner of this little state. I took to this lifestyle, and for this reason, I never encountered any kind of “culture shock” when I eventually left for Charleston. As southern cities go, Charleston is pretty damn cosmopolitan, but there remain vestiges of the old southern way of life that can sometimes annoy transplanted Yankees. I never experienced this—or, if I did, I was drawn to it as a reminder of home.

And home was and remains my place of comfort. Both my parents worked very hard, but they always had time for my brother and me. They never missed a soccer game, a baseball game, or a wrestling match. They never were too busy to help with homework. They always listened to our worries and troubles, and they didn’t act as if our childhood dramas were unimportant. Every night we would have dinner together, no matter what. It was our time together as a family, sharing stories of our day and working together as a single unit. These family dinners were so much a part of my upbringing that I just assumed that’s how everyone lived. It wasn’t until I was off on my own at college and later that I came to realize how precious and important those times around the table truly were. No, not everyone grew up like that. No, not everyone had a mom or dad who was around to listen to them, to enjoy their company, to build and grow a family into the strongest bond a person can have. There’s a reason why in later years, when the weight of my struggles bore down on me, that I often retreated to the comfort of home, to the relaxing and restorative presence of my family around the dinner table.

All of which is to say that of the many blessings I have had in life, none stand out as strongly as the life my parents provided to me growing up. I know that traumatic events that happen in childhood can often lead to severe internal problems in later years, but I can’t point to anything like that from my own early years. There was a time when, in the third grade, my aunt on my father’s side was killed in Baltimore. It was the first time I ever saw my father cry—a moment that stays with a child forever. It’s the moment when you first glimpse your parents, especially your father, as an actual person and not a marble icon. Some years later, when I was a sophomore in high school, my dad underwent heart surgery, and his recovery lasted several months. My father’s stay in the hospital had a profound effect on my future. At the time, I had very vague notions of becoming a doctor, but this was based on little more than trying to tie my academic performance to a successful profession. I had no real medical passion, a fact made painfully obvious when I visited my father in the hospital after his surgery. I never made it to his room in the ICU. There was something deeply unsettling to me about being in the hospital, and I found myself running outside before ever seeing him. So that knocked “doctor” off my list of possible careers.

A non-drinker, my father hated taking his pain medication, which made for a very sour patient that the rest of the family just had to deal with. Because I took over a lot of his home care, he directed much of his externalized anger and frustration toward me. Being older and aware of the reason, I took it in stride. But aside from these moments, which hardly rise to the level of traumatic memories, my childhood growing up in Ocean View, spending summers in Fenwick and Bethany Beach, was about as idyllic as a middle-class kid could ever want.

A NEW PASSION AND DEEP SCARS

What this safety and comfort instilled in me was self-confidence from a young age. I pursued my interests and hobbies without the typical adolescent worrying of what others might think. For the most part, these interests were your basic American boy interests, especially athletics. I loved all the sports that are popular on the East Coast, including soccer, lacrosse, and baseball, and I was good at them. Though skinny, I wasn’t yet at the level where my size worked against me, so I couldn’t even be self-conscious about that yet. But I also wasn’t that typical. When I’d come home from practice, I would turn on Emeril Lagasse and help my mother make dinner. My mom was a full-time schoolteacher by then, and she was more than happy to have a little help in the kitchen. For me, though, I genuinely enjoyed it. I even started to put together my own cookbook full of my favorite recipes. I suppose I was aware that this wasn’t what most boys my age did when they got home from school, but I didn’t care. Never much of a video-gamer, I simply loved to cook.

I started to recognize that I had an appreciation for the more domestic hobbies usually associated with girls, especially when I first learned to sew. Neither of my parents were particularly adept or interested in it, as far as I can remember. I first came across sewing in the seventh grade, in Mrs. Hurley’s home economics class. The classroom was divided into two sections, one half dedicated to the kitchen and cooking, the other to sewing, with several electronic sewing stations set up. As is typical for that age, most of the boys laughed their way through class, while most of the girls enjoyed it. I was with the girls. While I do think it’s true that these interests roughly break down by gender, I think far more of the boys enjoyed it than they were willing to admit. If it wasn’t sports, then they weren’t allowed to enjoy it. But I did, and I had no problem showing that I did. I remember making my first pillow in Mrs. Hurley’s class and feeling a sense of tremendous satisfaction at having created something. Using my hands, I had turned what had been some fabric and thread into something real and beautiful (to me, at least). I didn’t realize it at the time, but I had stumbled upon something that had given me joy. It was an amazing feeling, similar to what I felt when I sat down to a dinner I had helped prepare. I was too young to realize how precious that feeling really is, and perhaps for this reason I abandoned these hobbies as I got older. It wasn’t because I would grow self-conscious about these interests; rather, because my childhood was full of joy, I never expected to find myself in a place where I would need joy to get me through dark moments.

And those moments would strike soon enough. As a child and adolescent, I rarely experienced true cruelty. There was the typical teasing that boys and brothers inflict on one another, but nothing that rose to the level of outright viciousness. But if my childhood could be divided in half, much like Mrs. Hurley’s classroom, one half, the earlier half, was full of sunlight, happiness, and love. I had nothing to fear and had been able to develop my abilities and interests free of any outside interference. This would come to a swift end when I reached high school.

There’s no need to recount all the episodes of bullying that happened to me as a teenager. The best way to describe it is that it was just this persistent state of being for me, something that I had to deal with every day. Most of it originated with the older players on the school soccer team. Why did they target me? I was small and skinny, so I suppose that had something to do with it. I also believe that the self-confidence I had acquired and built throughout adolescence made me a target too. Bullies hate seeing what they lack in others, and their efforts are, above all, an attempt to make the target feel as bad as they do. In that, they were successful. I lost much of my confidence because of what they put me through, and I started to become painfully aware of my own inadequacies, to the point that they were all I focused on. I still carry these scars with me today. I developed a need to be liked by everyone, accepted as an equal. If I wasn’t good at something—or if I outright couldn’t do something—I chose to hide it rather than accept it. I just couldn’t bear the idea of anyone having a lesser opinion of me.

One particular moment stands out as emblematic of the bullying. I was a freshman on the junior varsity team, which shared a bus with the varsity players. I got off the bus one day and realized I had left behind my bookbag. The next day I retrieved my bag and reached in to take out one of the books for my English class. It was a thick, heavy book. Well, the older kids had used a whole roll of athletic tape on it, which I had to tear away. And when I finally got the book open, I realized that they had also smashed Doritos between the pages, leaving an oily residue that completely ruined the book, which I had to pay for. To some, it might seem that it’s just a book, so what? But I was a good, serious student. I appreciated my books and considered them valuable beyond their monetary price. For those players to deliberately destroy my book affected me deeply. To this day, I don’t understand that level of mindless cruelty. What didn’t they like about me? What had I done wrong?

With the benefit of hindsight, I sometimes look back on this episode and others like it and wonder if it was really that bad. But then I quickly remember that this was the same thing I had told myself back then. I wasn’t getting beaten up; I was just the mark for this group’s senseless viciousness. I wasn’t afraid for my safety or my life, but I was made to feel like there was a problem with me. Maybe it was my stature. Maybe it was my teeth, which weren’t the best before I got braces and whitened them. Maybe it was because I was a little geeky. Whatever it was, their purpose was to make me feel like garbage. And, like I said, they succeeded. I internalized their bullying to the point where I felt that something was wrong with me if they didn’t like me. This obsession with what others thought about me—by no means abnormal for a teenager—made me turn from a confident kid into someone who sought validation from others. I couldn’t be happy with myself unless others were happy with me. This was the bullies’ deepest cut, and the one that left a lasting mark. At the same time, I knew that one day I would prove them all wrong. I didn’t know how then, but their cruelty was motivation for me then and later.

Despite the prevalence of the bullying, I never got used to it. Some days were better than others, when the bullies simply forgot to make me a target, but that only led to agonizing uncertainty and paranoia. When I’d leave for school in the morning, I girded myself for what might happen. If I was bullied, then I had to deal with it. If I didn’t get bullied, then I was left with this pent-up anxiety that started to affect other aspects of my life. It was during these years when I developed some obsessive-compulsive tendencies. I don’t think I can attribute all of it to the bullying, since OCD definitely runs in my family, but like many mental health conditions, my OCD needed a trigger—and bullying was the trigger. For instance, my bedtime routine started to take forty-five minutes, because I had to look under my bed three times; I had to check the closet; I had to shut the doors just right; I had to turn off the lights just right; and I had to brush my teeth in a certain way that made me gag. In the mornings, I would repeat this process, and sometimes throw up my breakfast.

One day I had to serve an in-school suspension for an incident that was a result of the bullying. Before school, I had already thrown up my breakfast because of my OCD, and so went to serve the suspension on an empty stomach. For lunch, the school served only cheese sandwiches, which I couldn’t eat. Don’t ask me why. The single-slice Kraft cheese makes me nauseous. So I went without lunch that day. After the suspension, I had a wrestling match that just so happened to be against one of my main antagonists. I had never lost to this kid. In fact, I was undefeated. Everyone expected me to win—including myself. Except I hadn’t eaten anything all day and had no strength going into the match. I lost. On the way home that evening, my father could tell that something other than losing was bothering me, and I finally broke down. With tears running down my face, I explained why I had lost; I explained what had been going on at school; I explained why it took me forty-five minutes to get to bed each night, and why I left for school hungry that morning.

This was the first time I had ever tried to explain the impact of the bullying to my parents. There was so much shame that came with it, like I had let my parents down for becoming the bullies’ target. Again, this is the effect of the bullying itself, since it suggested I wasn’t strong enough to handle a little teasing. I don’t think that way anymore, and I remember feeling tremendously better after telling my father all the things I kept hidden from him. The reason I had not said anything before then was because I didn’t want to worry them. Listening to me spill my guts, my father understood the dilemma. He knew that, as a teenager, I wouldn’t want Dad and Mom coming to save me. But he also made it clear to me that he was always there to support me and help me through difficult moments in my life, no matter what. It was an offer that I would accept more than once in the years that followed. Still, it wouldn’t be until I started talking about the bullying on television that my mother finally understood the extent of it. I know it crushed her to hear how badly those years affected me, and that she blames herself for not seeing it at the time.

Eventually, as those older kids graduated, the bullying slowed and then stopped altogether. I went on living my life, playing sports, getting good grades, and otherwise enjoying my high school years. By the time I graduated, I felt like those years were behind me, that I had survived them, and I wouldn’t have to worry about the bullies ever again. I was right in some ways, but terribly wrong in others. The bullying might have stopped, but the scars would stay with me for many years.

A BUSINESS CHAMPION—KIND OF

I don’t want to leave the impression that my high school years were defined only by bullying. There were some pretty remarkable moments too, not just in sports but also in my academic pursuits. In particular, and quite relevant to this book, I was a member of the Business Professionals of America, which seeks to empower students with business and leadership skills. Several friends and I were members of BPA, and as juniors we had competed at the state championship in the category of small-business management. Much to our own surprise, we won the state tournament and had a chance to compete in the national competition at Disney World in Orlando.

There was a bit of a “David vs. Goliath” atmosphere to the national tournament, which was dominated by far wealthier private school teams. The other teams all showed up in matching uniforms; we were dressed in our plain clothes, just four public school kids from Indian River High School. Our feeling was that we were just along for the ride, happy to be there and enjoy a mini vacation at Disney. We didn’t go expecting much, and so wouldn’t have been terribly disappointed if we left with nothing. In fact, as we presented our business solution to the judges—it was based on revamping an ice-cream shop—they stopped us repeatedly and challenged several of our assertions. We all got the sense that the judges were trying to intimidate us, although I won’t go so far as to say that it was because we were public school kids from lower Delaware. I just think the judges felt we wouldn’t be as prepared as some of the more serious teams. But we didn’t back down. Two of our team members, Chad and Tom, had even worked at an ice-cream shop in Bethany Beach during the summer. That didn’t necessarily make them ice-cream professionals, but it certainly gave them far greater insight into the business than these judges had. The back-and-forth got quite heated, to the point that when we left the room, we felt that that either we had just earned the tournament win… or last place.

The next day was awards time, and we filed into a huge auditorium with five thousand other people. The organizers ran through each category, inviting each of the finalists onstage before announcing the winner in that group. When they got to the small business category and started calling up the top ten finalists one by one, the speaker announced, “Indian River High School,” and the four of us started smiling. We walked toward the stage amid the glares of the other teams who were furious that this ragtag group of public school kids had bested them. Onstage, looking out at this sea of people, the judges said they’d announce the top three, leaving the winner for the last. Third and second place were announced, and we all looked at one another. Holy shit, we’d won! So when the speaker once more said, “Indian River High School,” we just started laughing. Perhaps the best moment of that day was seeing our advisor, Mr. Murray, jumping up and down in his seat as the spotlight came to rest on his winning team.

Now, I don’t mean to suggest that our crushing victory at the BPA Nationals foretold any future business success. It’s not like I saw my career path as an entrepreneur or anything. But I’ve always been struck by how four kids with a little bit of street smarts were able to take down teams that were steeped in theory and formal business education. (The looks on their faces were pretty priceless.) I’m reminded of that triumph every now and then when debating future decisions for Sewing Down South. Sometimes all the education in the world simply exists to tell you why your idea is a bad one. You’ve learned enough to know that you don’t know anything, and you become paralyzed or guided by fear. You don’t pursue the chances you should because all the business books tell you they won’t work.

Well, sometimes they do work. Sometimes listening to your gut and going off your own experience is the right path forward.

COLLEGE AND CHARLESTON

By the time I was old enough to start thinking about college, I only knew this much: I was ready to leave home. I didn’t know where yet. I just knew that my path was beyond the confines of Delaware. I wasn’t running away, either. Yes, the bullying had left a deep and lasting impression on me, but it wasn’t the reason I wanted to leave home. It was more like I was running toward something. I felt I had done all that I could in this little corner of the world and that it was time for a fresh start (and independence) elsewhere. I guess you could say that I had the same feeling the early American settlers had had when they looked out across the expansive West. There I would find my fortune.

I applied to several colleges but had no strong feelings about any of them. That’s when my friend Sean told me about the College of Charleston. It wasn’t like Charleston was any sort of destination for me. I didn’t have thoughts about the city one way or the other. But then I went down for a visit. I realized, Yes, this is where I’m going to go to school. I was close to my beloved Atlantic Ocean; I was in a culture and a lifestyle that wasn’t frenzied or manic. (The sight of the southern women didn’t hurt either.) And while there was a feeling of familiarity with Charleston, coming from “lower, slower Delaware,” there was also a vibrancy that excited me. The city was in the middle of a cultural renaissance, with the Old South—and birthplace of the Confederacy—giving way to this younger, more socially aware wave of outsiders. In other words, Charleston had become a destination for those who appreciated the city’s beauty and wanted to help it move beyond its more traditional roots. There was also a pretty kick-ass partying scene that certainly impressed a kid like me.

In trying to place my college years in the narrative of this book, there are two points that stand out. The first was coming to some understanding of what I wanted to do with my life. I had mentioned the idea of being a doctor earlier—only to learn that hospitals were horrible places for me. I had left behind any notion of pursuing sewing or the other domestic crafts that I had fallen in love with as a child. Those were personal interests, but hardly career-worthy pursuits, or so I thought. I was smart, but I had no firm direction toward a specific intellectual passion. Looking back now, I regret that I wasn’t introduced to the field of engineering at an early age. The mathematics and the science inherent in engineering were two fields I had always excelled in, and was even passionate about. But I came to this realization too late in life, certainly if one wanted to be an engineer, whose career path begins freshman year in college.

But then there was the law.

On Southern Charm, viewers were right to question my commitment to the law, especially in those earlier seasons. Lawyers must necessarily be hardworking, disciplined professionals—the very qualities I lacked in my mid-twenties. I can laugh at the joke now, even if I want to correct the record a bit. I did fall in love with the law in college. There were a couple moments that are worth mentioning. The first is that during my junior year I was arrested for public intoxication. It was, in fact, a case of mistaken identity (they later caught the real culprit), but it left a lasting impression on me. My father called a friend of his who was an attorney to ask for his advice. After hearing my story, he decided to represent me in court and got the charges dismissed. The whole process fascinated me, not least because I felt like I had been wronged by the system. Being punished for something I didn’t do opened my eyes to the harsh reality of the judicial system. Yes, it often works as it’s supposed to, but it also sometimes doesn’t. And to say that no system is perfect doesn’t do much for those wrongly accused or convicted. Even as a child, and especially as an adolescent or teenager, injustice affected me deeply. I still remember being on that soccer bus when the bullies had turned their sights on another kid, and sticking up for him. I knew what it would (and did) lead to, but I can’t stand watching others suffer unjustly at the hands of bullies.

This growing passion and fascination with the law was also spurred by a course I took on federal courts in my junior year, taught by a federal magistrate. My eyes were opened to the inner workings of a system whose roots stretch back centuries. And the ones who have knowledge of this fascinating system, and know how to navigate it, are lawyers. Their job is to seek justice—and put down the bullies. I was in.

That’s the righteous part of my decision to go to law school. There remains a more banal and unflattering one. Law school seemed like a surefire way to become wealthy and successful. I didn’t have a driving need to make money because of the circumstances of my upbringing, although my brother’s and my love of good food and travel continually perplexes my parents, who rarely experienced either. I wanted to make money because I wanted to “make it.” I wanted to feel successful by having all the trappings of success. I also saw the law as a way to achieve financial freedom, to live the way I wanted to, and even to give back if I could. I felt like becoming a lawyer would prove to all the bullies back home that I had succeeded, despite their best attempts. My revenge was my success. While this isn’t the best reason to go to law school, I also don’t think I’m unique in having less-than-savory motives for choosing a profession like the law. But I will admit that I was very much responding to the scars that the bullying had left on me.

Besides, for a procrastinator like me, law school offered a structured path forward. I could delay my entry into the real world another three years and come out of it with a six-figure associate’s salary. Yeah, I was definitely in.

THE BEGINNINGS OF ADDICTION

The other point I should make about my college years is that this is when I first started taking Adderall, and that’s because my procrastination didn’t start to become a problem until I went to college. Then it became a big problem. In high school, I was sheltered by the structure of my family life. When one was home on a school night, there wasn’t much else to do other than schoolwork. That structure disappeared in college, and I often found myself overwhelmed by the plethora of distractions. There was always something else I could be doing besides studying. I went from getting As in high school to getting four Ds one semester during my sophomore year in college. It was toward the end of my first semester junior year that my roommate gave me an Adderall, telling me it would help me study. I had never taken a pill like that before. But, damn, did the little thing work. It was like a light went off in my brain that said, “THIS is what we’ve needed all along!” By the end of my junior year, I was taking business administration and finance classes, which I loved, and got on the Dean’s List with a 3.8 GPA. Not surprisingly, I gave all the credit to my new friend.

Which isn’t to say that I spent all my time in the library. I did go to the library, where I would pop a pill and study for several hours. But Adderall keeps going even if you’ve finished the task you took it for in the first place. So, whether it was nine o’clock at night or one in the morning, I’d go from the library to a bar or a party. I had grown into myself while at college, and the girls had noticed. I had always been shy, but I learned that I transformed into this new charismatic person after just a few drinks. I quickly became very acquainted with the Charleston social scene, befriending all the bartenders and club owners, who often extended invitations to my friends and me to exclusive openings because they knew we’d bring the girls. I stopped being an outsider and carved out my own place in this young, vibrant town. Everywhere I went, I knew someone, whether they were a student or a local. One of the students a few years ahead of me, Jerry Casselano, bounced at a favorite bar of mine and would let me in even though I wasn’t twenty-one. Jerry would remember me years later when he was running his own sports marketing firm, and he would make a call that would change both our lives.

Adderall helped me study, but it didn’t solve my procrastination. For instance, I realized quite quickly—and this would become a major problem in law school—that I could avoid doing most of the work during the semester if I pulled some all-nighters at the end. For most people, this is an unsustainable behavior, but with Adderall, I could do it. I could study all night, night after night. While I still wasn’t taking the drug recreationally—by which I mean, for partying—I started to use it whenever I needed to accomplish anything. Suddenly, I found reasons to drive home to Delaware, instead of fly, because Adderall made the trip fun. The little pill would focus my mind in a way that felt superhuman.

I eventually approached my parents about it, since I wanted them to know I was doing something about my academic decline. Taking it without their knowledge had felt shady, and I hated that feeling. And to be honest, Adderall is a bit of a truth serum. Once I started talking, I just kept going. I was still nervous to tell them, for all the reasons I was nervous to tell them anything, because I thought they would worry. Both my parents had stopped drinking when I was born, and to this day they remain absolutely sober. Taking a pill, even one that has appropriate medical uses, seemed like something they’d be against. Except my mother wasn’t. “Oh, Craig, I’ve known you should have been on something since grade school, you just never needed it,” she said when I spilled. As a schoolteacher, my mother was well aware of ADHD, and she had long suspected that I suffered from it. She wasn’t wrong. My father was supportive, too, but he also saw the early stages of what was to become an addiction. When I was home from school, I’d typically wait to pack until the very last moment, then I’d stay up all night packing. These are behaviors that parents catch on to. So while they were supportive of me getting a prescription to combat my ADHD, even then my father was aware that I wasn’t always taking it for the right reasons.

“I KNOW JUST THE GUYS”

Still, it would be some years before I started to really abuse Adderall. I had come to rely on it more and more, but I also attributed all my later academic success to it. How could something so helpful to me be bad for me? In any case, with my grades greatly improved, I was accepted into the Charleston School of Law, with a partial scholarship, which I entered a year after graduation. I was excited. I was also confident. College had given me a much-needed dose of validation that seemed to sweep away the nightmares from my high school days. I was no longer just a geeky kid. I was still skinny, but I had also grown into my body. I had made lifelong friends and had become popular, not just in college but in the city itself. People knew me, and I was treated like a local at bars and restaurants. Charleston had become my home. And I had no intention of leaving. Three more years of nothing but school seemed about right.