Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

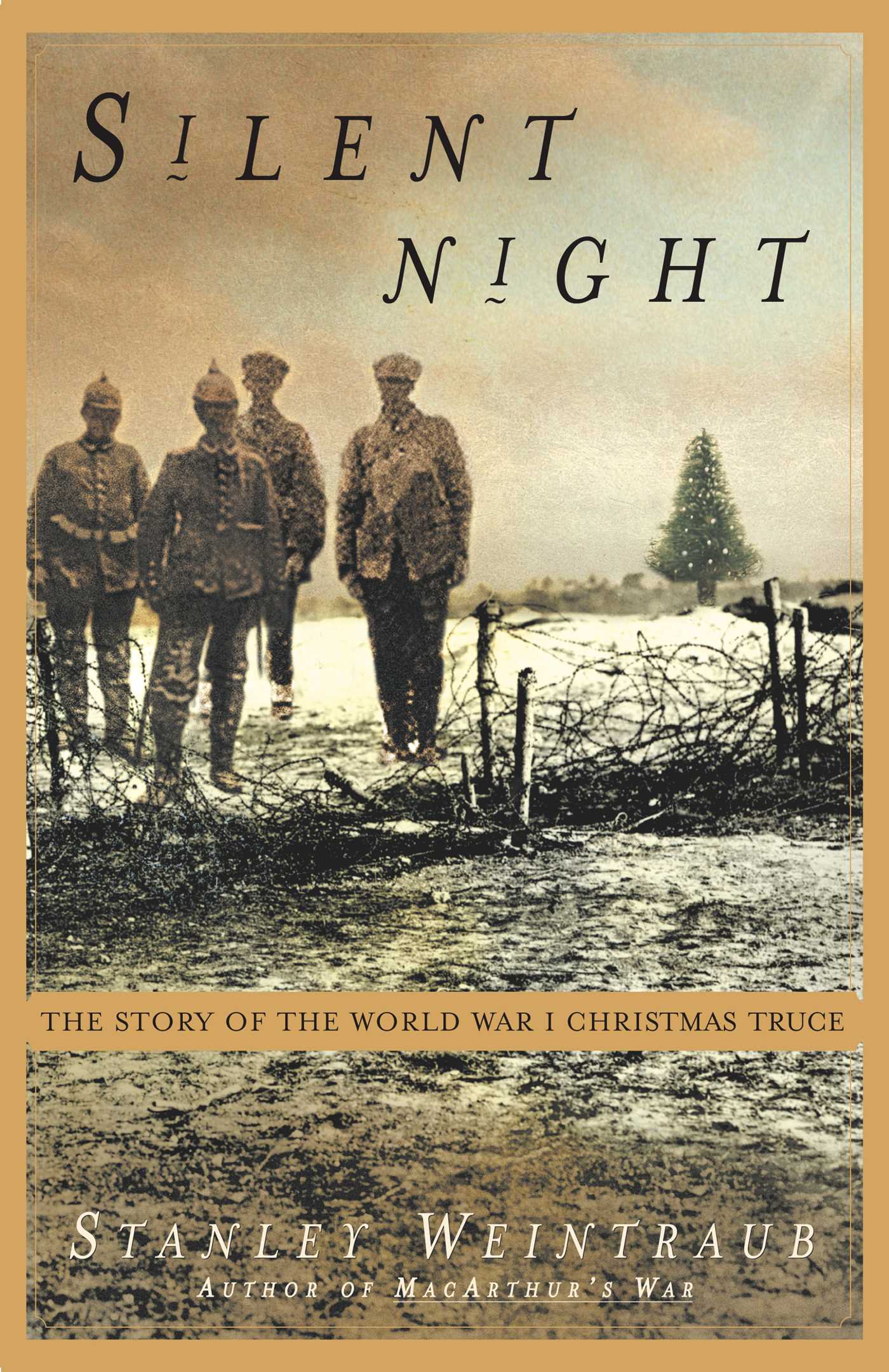

From an acclaimed military historian comes the astonishing story of World War I's 1914 Christmas truce—a spontaneous celebration when enemies became friends.

It was one of history's most powerful—yet forgotten—Christmas stories. It took place in the improbable setting of the mud, cold rain, and senseless killing of the trenches of World War I. It happened in spite of orders to the contrary by superiors. It happened in spite of language barriers. And it still stands as the only time in history that peace spontaneously arose from the lower ranks in a major conflict, bubbling up to the officers and temporarily turning sworn enemies into friends.

Silent Night, by renowned military historian Stanley Weintraub, magically restores the 1914 Christmas Truce to history. It had been lost in the tide of horror that filled the battlefields of Europe for months and years afterward. Yet, in December 1914, the Great War was still young, and the men who suddenly threw down their arms and came together across the front lines—to sing carols, exchange gifts and letters, eat and drink and even play friendly games of soccer—naively hoped that the war would be short-lived, and that they were fraternizing with future friends.

It began when German soldiers lit candles on small Christmas trees, and British, French, Belgian, and German troops serenaded each other on Christmas Eve. Soon they were gathering and burying the dead, in an age-old custom of truces. But as the power of Christmas grew among them, they broke bread, exchanged addresses and letters, and expressed deep admiration for one another. When angry superiors ordered them to recommence the shooting, many men aimed harmlessly high overhead.

Sometimes the greatest beauty emerges from deep tragedy. Surely the forgotten Christmas Truce was one of history's most beautiful moments, made all the more beautiful in light of the carnage that followed it. Stanley Weintraub's moving re-creation demonstrates that peace can be more fragile than war, but also that ordinary men can bond with one another despite all efforts of politicians and generals to the contrary.

It was one of history's most powerful—yet forgotten—Christmas stories. It took place in the improbable setting of the mud, cold rain, and senseless killing of the trenches of World War I. It happened in spite of orders to the contrary by superiors. It happened in spite of language barriers. And it still stands as the only time in history that peace spontaneously arose from the lower ranks in a major conflict, bubbling up to the officers and temporarily turning sworn enemies into friends.

Silent Night, by renowned military historian Stanley Weintraub, magically restores the 1914 Christmas Truce to history. It had been lost in the tide of horror that filled the battlefields of Europe for months and years afterward. Yet, in December 1914, the Great War was still young, and the men who suddenly threw down their arms and came together across the front lines—to sing carols, exchange gifts and letters, eat and drink and even play friendly games of soccer—naively hoped that the war would be short-lived, and that they were fraternizing with future friends.

It began when German soldiers lit candles on small Christmas trees, and British, French, Belgian, and German troops serenaded each other on Christmas Eve. Soon they were gathering and burying the dead, in an age-old custom of truces. But as the power of Christmas grew among them, they broke bread, exchanged addresses and letters, and expressed deep admiration for one another. When angry superiors ordered them to recommence the shooting, many men aimed harmlessly high overhead.

Sometimes the greatest beauty emerges from deep tragedy. Surely the forgotten Christmas Truce was one of history's most beautiful moments, made all the more beautiful in light of the carnage that followed it. Stanley Weintraub's moving re-creation demonstrates that peace can be more fragile than war, but also that ordinary men can bond with one another despite all efforts of politicians and generals to the contrary.

Excerpt

Introduction

Three myths would arise during the early months of the Great War. Burly Cossacks, sent by the Czar to bolster the Western Front, were seen embarking from British railway stations for Dover, still shaking the persistent snows of Russia from their boots. In France, during the British retreat from Mons, angels appeared -- spirit bowmen out of the English past -- to cover the withdrawal. And the third was that, to the dismay of the generals, along the front lines late in December 1914, opponents in the West laid down their arms and celebrated Christmas together in a spontaneous gesture of peace on earth and good will toward men. Only one of the myths -- the last -- was true.

In an issue sent to press just before Christmas, The New Republic, an American weekly writing from a plague-on-both-sides neutrality, accepted what seemed obvious. "If men must hate, it is perhaps just as well that they make no Christmas truce." A futile resolution had been introduced in the Senate in Washington urging that the belligerents hold a twenty-day truce at Christmas "with the hope that the cessation of hostilities at the said time may stimulate reflection upon the part of the nations [at war] as to the meaning and spirit of Christmas time."

Since early August the European war had claimed hundreds of thousands of killed, wounded, and missing. An appeal for a cease-fire at Christmas from Pope Benedict XV, elected just three months earlier, only weeks after war had broken out, had made headlines but was quickly rebuffed by both sides as "impossible." Rather, The New Republic suggested sardonically, "The stench of battle should rise above the churches where they preach good-will to men. A few carols, a little incense and some tinsel will heal no wounds." A wartime Christmas would be a festival "so empty that it jeers at us."

To many, the end of the war and the failure of the peace would validate the Christmas cease-fire as the only meaningful episode in the apocalypse. It belied the bellicose slogans and suggested that the men fighting and often dying were, as usual, proxies for governments and issues that had little to do with their everyday lives. A candle lit in the darkness of Flanders, the truce flickered briefly and survives only in memoirs, letters, song, drama and story.

"Live-and-let-live" accommodations occur in all wars. Chronicles at least since Troy record cessations in fighting to bury the dead, to pray to the gods, to negotiate a peace, to assuage war weariness, to offer signs of amity to enemies so long opposite in a static war as to encourage mutual respect. None had ever occurred on the scale of, or with the duration, or with the potential for changing things, as when the shooting suddenly stopped on Christmas Eve, 1914. The difference in 1914 was its potential to become more than a temporary respite. The event appears in retrospect somehow unreal, incredible in its intensity and extent, seemingly impossible to have happened without consequences for the outcome of the war. Like a dream, when it was over, men wondered at it, then went on with the grim business at hand. Under the rigid discipline of wartime command authority, that business was killing.

Dismissed in official histories as an aberration of no consequence, that remarkable moment happened. For the rival governments, for which war was politics conducted by persuasive force, it was imperative to make even temporary peace unappealing and unworkable, only an impulsive interval in a necessarily hostile and competitive world. The impromptu truce seemed dangerously akin to the populist politics of the streets, the spontaneous movements that topple tyrants and autocrats. For that reason alone, high commands could not permit it to gain any momentum to expand in time and in space, or to capture broad appeal back home. That it did not was more accident than design.

After a silent night and day -- in many sectors much more than that -- the war went on. The peace seemed nearly forgotten. Yet memories of Christmas 1914 persist, and underlying them the compelling realities and the intriguing might-have-beens. What if...?

Late in December 1999 a group of nine quirky "Khaki Chums" crossed the English Channel to Flanders with the "blatantly daft idea" of commemorating the truce where it may have begun, near Ploegsteert Wood in Belgium. Wearing makeshift uniforms recalling 1914, and working in the rain and snow, they dug trenches, reinforcing them with sandbags and planks which "literally disappeared into the bottomless mud." For several days they cooked their rations, reinforced their parapets, and slept soaked through to the skin. They also endured curious onlookers and enjoyed visits from the media. Before departing, the nine planted a large timber cross in the quagmire as a temporary mark of respect for the wartime dead, filled back their trenches and slogged homeward.

Months later they were astonished to learn that local villagers had treated their crude memorial with a wood preservative and set it in a concrete base. In season, now, poppies flower beneath it. Thousands of Great War monuments, some moving and others mawkish, remain in town squares and military cemeteries across Europe. The afterthought of the "Khaki Chums" lark in the Flanders mud is the only memorial to the Christmas Truce of 1914.

Copyright © 2001 by Stanley Weintraub

Three myths would arise during the early months of the Great War. Burly Cossacks, sent by the Czar to bolster the Western Front, were seen embarking from British railway stations for Dover, still shaking the persistent snows of Russia from their boots. In France, during the British retreat from Mons, angels appeared -- spirit bowmen out of the English past -- to cover the withdrawal. And the third was that, to the dismay of the generals, along the front lines late in December 1914, opponents in the West laid down their arms and celebrated Christmas together in a spontaneous gesture of peace on earth and good will toward men. Only one of the myths -- the last -- was true.

In an issue sent to press just before Christmas, The New Republic, an American weekly writing from a plague-on-both-sides neutrality, accepted what seemed obvious. "If men must hate, it is perhaps just as well that they make no Christmas truce." A futile resolution had been introduced in the Senate in Washington urging that the belligerents hold a twenty-day truce at Christmas "with the hope that the cessation of hostilities at the said time may stimulate reflection upon the part of the nations [at war] as to the meaning and spirit of Christmas time."

Since early August the European war had claimed hundreds of thousands of killed, wounded, and missing. An appeal for a cease-fire at Christmas from Pope Benedict XV, elected just three months earlier, only weeks after war had broken out, had made headlines but was quickly rebuffed by both sides as "impossible." Rather, The New Republic suggested sardonically, "The stench of battle should rise above the churches where they preach good-will to men. A few carols, a little incense and some tinsel will heal no wounds." A wartime Christmas would be a festival "so empty that it jeers at us."

To many, the end of the war and the failure of the peace would validate the Christmas cease-fire as the only meaningful episode in the apocalypse. It belied the bellicose slogans and suggested that the men fighting and often dying were, as usual, proxies for governments and issues that had little to do with their everyday lives. A candle lit in the darkness of Flanders, the truce flickered briefly and survives only in memoirs, letters, song, drama and story.

"Live-and-let-live" accommodations occur in all wars. Chronicles at least since Troy record cessations in fighting to bury the dead, to pray to the gods, to negotiate a peace, to assuage war weariness, to offer signs of amity to enemies so long opposite in a static war as to encourage mutual respect. None had ever occurred on the scale of, or with the duration, or with the potential for changing things, as when the shooting suddenly stopped on Christmas Eve, 1914. The difference in 1914 was its potential to become more than a temporary respite. The event appears in retrospect somehow unreal, incredible in its intensity and extent, seemingly impossible to have happened without consequences for the outcome of the war. Like a dream, when it was over, men wondered at it, then went on with the grim business at hand. Under the rigid discipline of wartime command authority, that business was killing.

Dismissed in official histories as an aberration of no consequence, that remarkable moment happened. For the rival governments, for which war was politics conducted by persuasive force, it was imperative to make even temporary peace unappealing and unworkable, only an impulsive interval in a necessarily hostile and competitive world. The impromptu truce seemed dangerously akin to the populist politics of the streets, the spontaneous movements that topple tyrants and autocrats. For that reason alone, high commands could not permit it to gain any momentum to expand in time and in space, or to capture broad appeal back home. That it did not was more accident than design.

After a silent night and day -- in many sectors much more than that -- the war went on. The peace seemed nearly forgotten. Yet memories of Christmas 1914 persist, and underlying them the compelling realities and the intriguing might-have-beens. What if...?

Late in December 1999 a group of nine quirky "Khaki Chums" crossed the English Channel to Flanders with the "blatantly daft idea" of commemorating the truce where it may have begun, near Ploegsteert Wood in Belgium. Wearing makeshift uniforms recalling 1914, and working in the rain and snow, they dug trenches, reinforcing them with sandbags and planks which "literally disappeared into the bottomless mud." For several days they cooked their rations, reinforced their parapets, and slept soaked through to the skin. They also endured curious onlookers and enjoyed visits from the media. Before departing, the nine planted a large timber cross in the quagmire as a temporary mark of respect for the wartime dead, filled back their trenches and slogged homeward.

Months later they were astonished to learn that local villagers had treated their crude memorial with a wood preservative and set it in a concrete base. In season, now, poppies flower beneath it. Thousands of Great War monuments, some moving and others mawkish, remain in town squares and military cemeteries across Europe. The afterthought of the "Khaki Chums" lark in the Flanders mud is the only memorial to the Christmas Truce of 1914.

Copyright © 2001 by Stanley Weintraub

Product Details

- Publisher: Free Press (November 11, 2001)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439107133

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Robert Cowley founding editor of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, and editor of No End Save Victory: Perspectives on World War II Stanley Weintraub's poignant account of the day one of the worst of wars took a holiday sounds like the stuff of fiction, but it was the sort of event that fiction can only imitate. No wonder that his book reads like a novel, a true story that has the power to haunt.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Silent Night eBook 9781439107133

- Author Photo (jpg): Stanley Weintraub Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit