Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

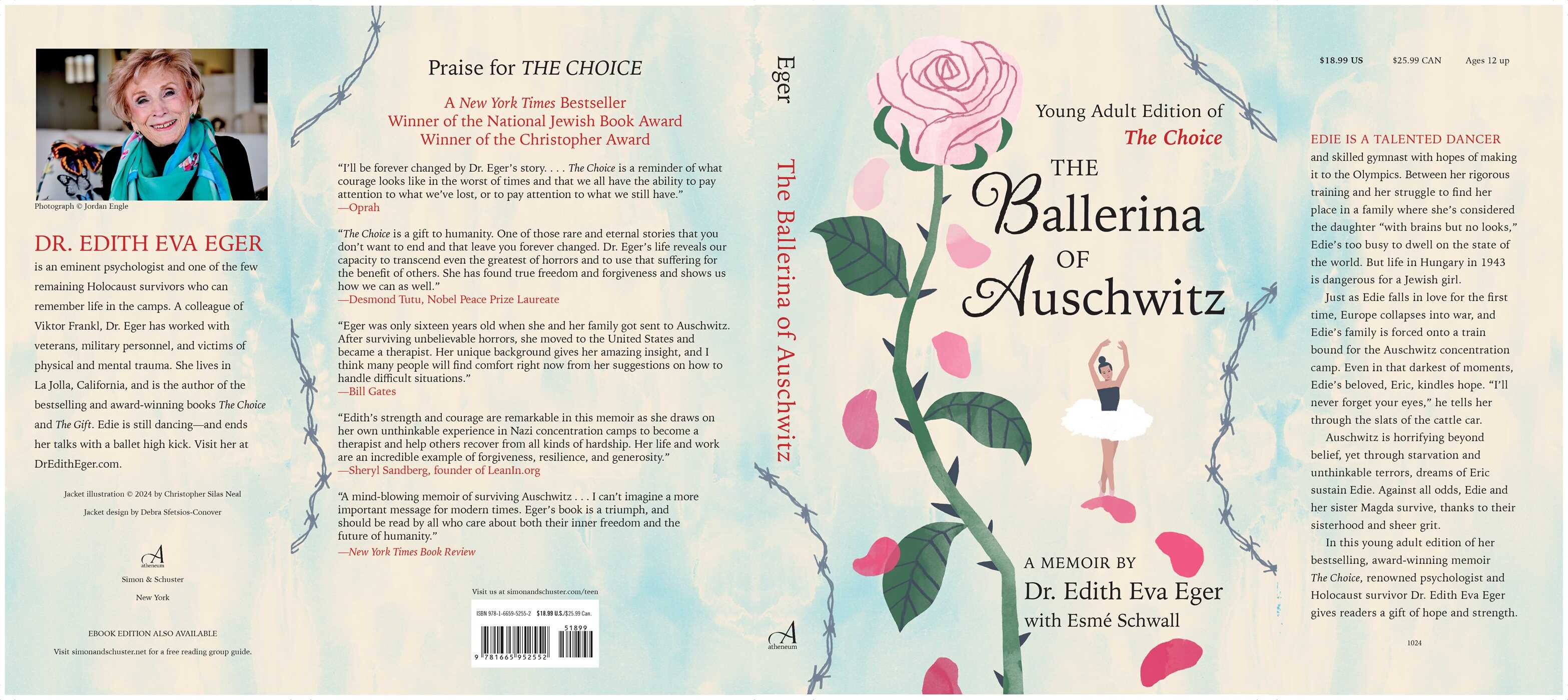

About The Book

In this “luminous” (Kirkus Reviews, starred review) young adult edition of the bestselling, award-winning memoir The Choice, Holocaust survivor and renowned psychologist Dr. Edith Eva Eger shares her harrowing experiences and gives readers the gift of hope and strength.

Edie is a talented dancer and a skilled gymnast with hopes of making the Olympic team. Between her rigorous training and her struggle to find her place in a family where she’s the daughter “with brains but no looks,” Edie’s too busy to dwell on the state of the world. But life in Hungary in 1943 is dangerous for a Jewish girl.

Just as Edie falls in love for the first time, Europe collapses into war, and Edie’s family is forced onto a train bound for the Auschwitz concentration camp. Even in those darkest of moments, Edie’s beloved, Eric, kindles hope. “I’ll never forget your eyes,” he tells her through the slats of the cattle car. Auschwitz is horrifying beyond belief, yet through starvation, unthinkable terrors, and daily humiliations like being forced to dance for a Nazi leader, dreams of Eric sustain Edie. Against all odds, Edie and her sister Magda survive, thanks to their sisterhood and sheer grit.

Edie returns home filled with grief and guilt. Survival feels more like a burden than a gift—until Edie recognizes that she has a choice. She can’t change the past, but she can choose how to live and even to love again.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 THE LITTLE ONE

They wanted a boy, but they got me.

A girl. A third daughter, the runt of the family.

“I’m glad you have brains because you have no looks,” my mother often tells me. Maybe she means that I’ll never be beautiful. Or maybe this compliment wrapped in criticism is her way of encouraging me to study hard. Motivation expressed as caution. Maybe there’s some invisible fate she’s trying to spare me. Maybe she’s trying to give me some better idea of who I might become. “You can learn to cook some other time,” she told me when I asked her to teach me to braid challah or fry chicken or make the cherry jam she preserves in summer and tucks away for the rest of the year. “You go back to school.”

Today, I stand in front of the mirror in the bathroom in our apartment, brushing my teeth, getting ready for school. I study my reflection. Is it true that I have no looks? I’m a dancer and a gymnast, my body lean and muscular. I like my strength. I like my wavy brown hair—though Magda, my oldest sister, is the pretty one. But when I meet my own eyes in the mirror, when I sink into that mysterious and familiar blue green, I can’t put my finger on what I see. It’s like I’m on the outside of my life, looking in, watching myself like a character in a novel, her destiny unknown, her heart and self still unfolding.

I’ve just finished reading one of my mother’s novels, Émile Zola’s Nana, pilfered from her bookshelf and devoured in secret. I can’t get the last scene out of my head. Nana, the beautiful, chic performer, the one who was desired by so many men, lies broken and diseased, her body erupted in smallpox sores. There’s something terrifying in the way her body is described. Even before the smallpox, even when she was still gorgeous and charming, her body was dangerous. A weapon. Threatening, something of which to beware.

Yet she was wanted. I’m hungry for a love like that. To be seen and known as a treasure. To be showered with affection, savored like a feast.

Instead, I’m taught caution.

“Washing up is like doing the dishes,” my mother has told me. “Start with the crystal, then work your way down to the pots and pans.” Save the dirtiest for last. Even my own body is suspect.

Magda raps on the bathroom door, tired of waiting her turn.

“Stop dreaming, Dicuka,” she complains. She uses the pet name my mother invented for me. Ditzu-ka. These nonsense syllables are usually warmth to me. Today they are harsh and clanging.

I hurry past my irritated sister toward our shared bedroom to dress, still thinking of the girl in the mirror—the girl longing for love. Maybe the kind of love I crave is impossible. I have spent thirteen years stitching together my memories and experiences into a story of who I am, a story that seems to reveal that I’m damaged, that I’m not wanted, that I don’t belong.

Like the night when I was seven and my parents hosted a dinner party. They sent me out of the room to refill a pitcher of water, and from the kitchen I heard them joke, “We could have saved that one.” They meant that before I came along, they were already a complete family. They had Magda, who played piano, and Klara, the violin prodigy. I didn’t bring anything new to the table. I was unnecessary, not good enough. There was no room for me.

I tested this theory when I was eight and decided to run away. I would see if my parents even knew I was gone. Instead of going to school, I took the trolley to my grandparents’ house. I trusted my grandparents—my mother’s father and stepmother—to cover for me. They engaged in a continuous war with my mother on Magda’s behalf, hiding cookies in my sister’s dresser drawer. They were safety to me. They held hands, something my own parents never did. They were pure comfort—the smell of brisket and baked beans, of sweet bread, of cholent, a rich stew that my grandmother brought to the bakery to cook on Sabbath, when Orthodox practice did not permit her to use her own oven.

My grandparents were happy to see me. I didn’t have to perform for their love or approval. It was freely given, and we spent a wonderful morning in the kitchen, eating nut rolls. But then the doorbell rang. My grandfather went to answer it. A moment later he rushed into the kitchen. He was hard of hearing, and he spoke his warning too loudly. “Hide, Dicuka!” he yelled. “Your mother’s here!” In trying to protect me, he gave me away.

What bothered me the most was the look on my mother’s face when she saw me in my grandparents’ kitchen. It’s not just that she was surprised to see me here—it was as though the very fact of my existence had taken her by surprise. As though I was not who she wanted or expected me to be.

Yet I am often her companion, sitting in the kitchen with her when my dad is away on business trips to Paris, filling suitcases with silk for his tailoring business, my mother rigid and watchful when he returns, worried that he’s spent too much money. She doesn’t invite friends over for visits. There’s no easy gossip in the parlor, no discussions of books or politics. I’m the one to whom my mother tells her secrets. I cherish the time I spend alone with her.

One evening when I was nine, we were alone in the kitchen. She was wrapping up the leftover strudel that she’d made with dough I’d watched her cut by hand and drape like heavy linen over the dining room table. “Read to me,” she said, and I fetched the worn copy of Gone with the Wind from her bedside table. We had read it through once before. We’d begun again. I paused over the mysterious inscription, written in English, on the title page of the translated book. It was in a man’s handwriting, but not my father’s. All that my mother would say is that the book was a gift from a man she met when she worked at the Foreign Ministry before she knew my father.

We sat in straight-backed chairs near the woodstove. When we read together, I didn’t have to share her with anyone else. I sank into the words and the story and the feeling of being alone in a world with her. Scarlett returns to Tara at the end of the war to learn her mother is dead and her father is far gone in grief. “As God is my witness,” Scarlett says, “I’m never going to be hungry again.” My mother closed her eyes and leaned her head against the back of the chair. I wanted to climb into her lap. I wanted to rest my head against her chest. I wanted her to touch her lips to my hair.

“Tara…,” she said. “America, now that would be a place to see.” I wished she would say my name with the same softness she reserves for a country where she’s never been. All the delicious smells of my mother’s kitchen were mixed up for me with the drama of hunger and feast—always, even in the feast, that longing. I didn’t know if the longing was hers or mine or something we shared.

We sat with the fire between us.

“When I was your age…,” she began.

Now that she was talking, I was afraid to move, afraid she wouldn’t continue if I did.

“When I was your age, the babies slept together, and my mother and I shared a bed. One morning I woke up because my father was calling to me, ‘Ilonka, wake up your mother. She hasn’t made breakfast yet or laid out my clothes.’ I turned to my mother next to me under the covers. But she wasn’t moving. She was dead.”

I wanted to know every detail about this moment when a daughter woke beside a mother she had already lost. I also wanted to look away. It was too terrifying to think about.

“When they buried her that afternoon, I thought they had put her in the ground alive. That night, Father told me to make the family supper. So that’s what I did.”

I waited for the rest of the story. I waited for the lesson at the end, or the reassurance.

“Bedtime” was all my mother said. She bent to sweep the ash under the stove.

Footsteps thumped down the hall outside our door. I could smell my father’s tobacco even before I heard the jangle of his keys.

“Ladies,” he called, “are you still awake?” He came into the kitchen in his shiny shoes and dapper suit, his big grin, a little sack in his hand that he gave me with a loud kiss to the forehead. “I won again,” he boasted. Whenever he played cards or billiards with his friends, he shared the spoils with me. That night he’d brought a petit four laced in pink icing. If I were my sister Magda, my mother, always concerned about Magda’s weight, would snatch the treat away, but she nodded at me, giving me permission to eat it.

She stood up, on her way from the fire to the sink. My father intercepted her, lifted her hand so he could twirl her around the room, which she did, stiffly, without a smile. He pulled her in for an embrace, one hand on her back, one teasing at her breast. My mother shrugged him away.

“I’m a disappointment to your mother,” my father half whispered to me as we left the kitchen. Did he intend for her to overhear, or was this a secret meant only for me? Either way, it is something I stored away to mull over later. Yet the bitterness in his voice scared me. “She wants to go to the opera every night, live some fancy cosmopolitan life. I’m just a tailor. A tailor and a billiards player.”

My father’s defeated tone confused me. He is well known in our town, and well liked. Playful, smiling, he always seems comfortable and alive and fun to be around. He goes out with his many friends. He loves food—especially the ham he sometimes smuggles into our household, eating it over the newspaper it is wrapped in, pushing bites of forbidden pork into my mouth, enduring my mother’s accusations that he is a poor role model. His tailor shop has won two gold medals. He isn’t just a maker of even seams and straight hems. He is a master of couture. That’s how he met my mother—she came into his shop because she needed a dress, and his work came so highly recommended. But he had wanted to be a doctor, not a tailor, a dream his father had discouraged, and every once in a while, his disappointment in himself surfaced.

“You’re not just a tailor, Papa,” I reassured him. “You’re a famous dress designer!”

“And you’re going to be the best-dressed lady in Košice,” he told me, patting my head. “You have the perfect figure for couture.”

He’d pushed his disappointment back into the shadows. We stood together in the hall, neither one of us quite ready to break away.

“I wanted you to be a boy, you know,” my father said. “I slammed the door when you were born. I was that mad at having another girl. But now you’re the only one I can talk to.” He kissed my forehead.

I still love my father’s attention. Like my mother’s, it is precious… and precarious. As though my worthiness of their love has less to do with me and more to do with their loneliness. As though my identity isn’t about anything that I am or have and only a measure of what each of my parents is missing.

When I join my family at the breakfast table, my older sisters greet me with the song they invented for me when I was three and one of my eyes became crossed in a botched medical procedure. “You’re so ugly, you’re so puny,” they sing. “You’ll never find a husband.”

For years, I turned my head toward the ground when I walked so that I didn’t have to see anyone looking at my lopsided face. I had surgery when I was ten to correct the crossed eye, and now I should be able to lift my head and smile when I meet strangers, yet the self-consciousness persists, helped along by my sisters’ teasing.

Magda is nineteen, with sensual lips and wavy hair. She is the jokester in our family. When we were younger, she showed me how to drop grapes out of our bedroom window into the coffee cups of the patrons sitting on the patio below. Klara, the middle sister, the violin prodigy, mastered the Mendelssohn violin concerto when she was five.

I am used to being the silent sister, the invisible one. I’m so convinced of my inferiority that I rarely introduce myself by name. “I am Klara’s sister,” I say. It doesn’t occur to me that Magda might tire of being the clown, that Klara might resent being the prodigy. She can’t stop being extraordinary, not for a second, or everything might be taken from her—the adoration she’s accustomed to, her very sense of self. Magda and I have to work at getting something we are certain there will never be enough of; Klara has to worry that at any moment she might make a fatal mistake and lose it all. Klara has been playing violin all my life, since she was three. Often she stands in front of an open window to practice, as though she can’t fully enjoy her creative genius unless she can summon an audience of passersby to witness it. It seems that for her, love is not boundless, it’s conditional—the reward for a performance, what you settle for. And there’s a price to being loved: the work of being accepted and adored is in the end a kind of vanishing.

We eat buns from the bakery down the street smothered in butter and my mother’s apricot jam, more sweet than sour. My mother pours coffee and hands food around the table. My father has already hung a tape measure around his neck and tucked a piece of chalk in his breast pocket for marking fabric. Magda waits for my mother to offer a second helping of buns. “Take it. I’ll eat it,” she always urges me if I decline a second helping. Klara clears her throat, and everyone turns in her direction to hear what she will say.

“I have to reply to the professor about the invitation to study in New York,” she says, her knife smoothing the soft butter across the warm bread.

“We have family in New York,” my father muses, stirring his coffee. He means his sister Matilda, who lives in a place called the Bronx, in a Jewish immigrant neighborhood.

“No,” my mother says. “We’ve already discussed this. America is too far away.”

I think of that long-ago night in the kitchen when she spoke of America with such yearning. Maybe this is what life is, a constant waffling between the things we don’t have but wish we did and the things we have but wish we didn’t.

Klara squares her jaw. “If not New York,” she says, “then Budapest.”

My mother drops her head as she clears plates from the table. To support the career of the favorite child means losing her. Or maybe it’s not the idea of Klarie leaving home that makes her sad; maybe it’s her own intransigence. Maybe she’s angry with herself for saying no when she wants to be saying yes.

My father’s chronic good mood is unperturbed by the weight of Klara’s decision or the worry with which my mother carries it.

“We’ll talk about it,” he says, dispatching the somber mood that’s descended once again over our family table. Then he turns to me. “Dicuka,” he says, handing me an envelope, “bring this money to school. Tuition’s due.”

I hold the envelope in my hand, feeling the significance of his trust. Yet his handing over of this responsibility is also an admonishment. A reminder of what I cost the family. An open question about the value I bring. I hold tightly to the envelope as I gather my things for school, as though my grip on it will help me to pinpoint how much I matter and how much I don’t, as though it will help me to draw the map that shows the dimensions and the borders of my worth.

I am happiest when I am alone, when I can retreat into my inner world, and the walk to the private Jewish school I attend is time I prize. I practice the steps to “The Blue Danube” routine my ballet class will perform at a festival on the river.

I think of my ballet master and his wife, of the feeling I get when I take the steps up to the studio two or three at a time and kick off my school clothes, pull on my leotard and tights. I have been studying ballet since I was five years old, since my mother intuited that I wasn’t a musician, that I had other gifts. (My parents had tried to start me on Klara’s old violin, but it didn’t take long before my mother was pulling the instrument out of my hands, saying, “That’s enough.”) Ballet, though—I loved it from the start. My aunt and uncle gave me a tutu that I wore to my first lesson. Somehow, I didn’t feel shy in the studio. I walked straight up to the pianist who played music for the class to dance to and asked what pieces he planned to play. “Go dance, honey,” he told me. “I’ll take care of the piano.”

By the time I was eight, I was going to ballet classes three times a week. I liked doing something that was all mine, different from my sisters. And I liked being in my body. I liked practicing the splits, our ballet master reminding us that strength and flexibility are inseparable—for one muscle to flex, another must open; to achieve length and limberness, we have to hold our cores strong. I held his instructions in my mind like a prayer. Down I went, spine straight, abdominal muscles tight, legs stretching apart. I knew to breathe, especially when I felt stuck. I pictured my body expanding like the strings on my sister’s violin, finding the exact place of tautness that made the whole instrument ring. And then I was down. I was there. In the full splits. “Brava!” My ballet master clapped. “Stay right as you are.” He lifted me off the ground and over his head. It was hard to keep my legs fully extended without the floor to push against, but for a moment I felt like an offering. I felt like pure light. “Editke,” my teacher said, “all your ecstasy in life is going to come from the inside.” I don’t yet really understand what he meant. But I know that I can breathe and spin and kick and bend. That as my muscles stretch and strengthen, every movement, every pose seems to call out: I am, I am, I am. I am me. I am somebody.

Invention takes hold, and I am off and away in a new dance of my own, one in which I imagine my parents meeting. I dance both of their parts. My father does a slapstick double-take when he sees my mother walk into the room. My mother spins faster, leaps higher. I make my whole body arc into a joyful laugh. I have never seen my mother rejoice, never heard her laugh from the belly, but in my body, I feel the untapped well of her happiness.

When I get to school, the tuition money my father gave me to cover an entire quarter of school is gone. Somehow, in the flurry of dancing, I have lost it. I check every pocket and crease of my clothing, but it is gone. All day the dread of telling my father burns like ice in my gut.

At home that night, I wait till after dinner to muster the courage to tell my father what I’ve done. He can’t look at me as he raises his fist, gripping a belt. This is the first time he has ever hit me, or any of us. He doesn’t say a word to me when he is done.

I crawl into bed early, before my homework is finished, my back and bottom still burning. What hurts more than the fresh welts on my skin is the feeling that something is wrong with me. Soon I will come to know that the deep place I go in solitude is an asset, a survival tool, but tonight my imagination feels like an aberration. A terrible flaw.

I pull my doll under the covers. I call her Little One. She has long wavy dark hair and green eyes that open and close. Green eyes like my father’s. She’s a beautiful doll, my favorite possession. I whisper into her smooth porcelain ear.

“I wish I would die so he’d suffer for what he did to me,” I say, my eyes clenched tight in the dark.

The Little One is quiet, as though considering this consuming anger I have at my father—and at myself. I let the fury churn in me. I whip it higher, steeper. There’s pleasure in saying the worst possible things.

“No,” I whisper to my doll, my voice ragged with tears, “I wish…” I let the crescendo build…. “I wish…” I will say it, the most violent and terrible thing I can think. A sentence so dreadful that I can’t ever take it back, that I don’t know yet will haunt me, will replay in my mind on far worse nights, at much darker times. “I wish my father was dead,” I say.

Tonight the Little One says nothing, her eyes closed in the dark, a curtain pulled swiftly across the stage.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (October 1, 2024)

- Length: 192 pages

- ISBN13: 9781665952552

- Grades: 7 and up

- Ages: 12 - 99

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

★ “Eger’s present-tense stream-of-consciousness narrative allows readers to experience the brutality of the Nazis but also the cooperation and encouragement among the inmates and the events that gave her postwar life meaning. A luminous memoir of human resilience.”

– Kirkus Reviews, STARRED REVIEW

★ “Eger pares down The Choice, her National Jewish Book Award–winner and New York Times best-selling combination Holocaust memoir and self-help book, into a sensitive, thought-provoking account for teens. . . . Impactful for all readers, especially history enthusiasts or fellow trauma survivors.”

– Booklist, STARRED REVIEW

“Eger beautifully portrays liberation and returning to the world of the living. Dancing is the thread that holds her life together . . . Eger’s reflections of suffering and seeds of hope are directly and beautifully wrought; the author’s note reaches out to readers who are coping with pain and suffering in this modern age. . . . this is an important personal telling of Holocaust suffering and survival.”

– School Library Journal

Awards and Honors

- AJL Sydney Taylor Book Award Notable Book

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Ballerina of Auschwitz Hardcover 9781665952552

- Author Photo (jpg): Edith Eva Eger Jordan Engle(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit