Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

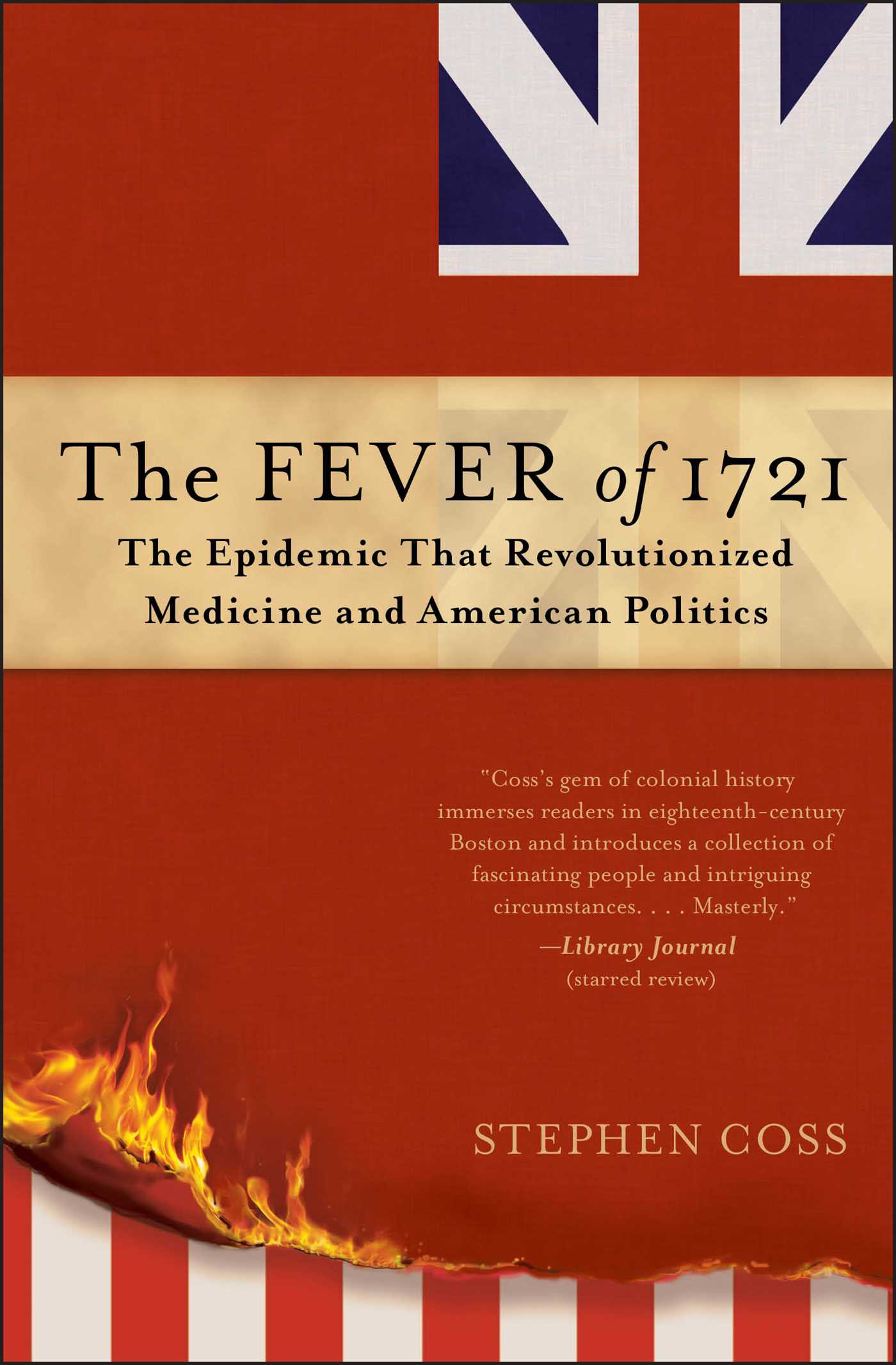

The “intelligent and sweeping” (Booklist) story of the crucial year that prefigured the events of the American Revolution in 1776—and how Boston’s smallpox epidemic was at the center of it all.

In The Fever of 1721 Stephen Coss brings to life the amazing cast of characters who changed the course of medical history, American journalism, and colonial revolution: Cotton Mather, the great Puritan preacher, son of the President of Harvard College; Zabdiel Boylston, a doctor whose name is on one of Boston’s avenues; James Franklin and his younger brother Benjamin; and Elisha Cooke and his protégé Samuel Adams.

Coss describes how, during the worst smallpox epidemic in Boston history Mather convinced Doctor Boylston to try making an incision in the arm of a healthy person and implanting it with smallpox matter. Public outrage forced Boylston into hiding and Mather’s house was firebombed.

“In 1721, Boston was a dangerous place…In Coss’s telling, the troubles of 1721 represent a shift away from a colony of faith and toward the modern politics of representative government” (The New York Times Book Review). Elisha Cooke and Samuel Adams were beginning to resist the British in the run-up to the American Revolution. Meanwhile, a bold young printer names James Franklin launched America’s first independent newspaper and landed in jail. His teenaged brother and apprentice, Benjamin Franklin, however, learned his trade in James’s shop and became a father of the Independence movement.

One by one, the atmosphere in Boston in 1721 simmered and ultimately boiled over, leading to the full drama of the American Revolution. “Fascinating, informational, and pleasing to read…Coss’s gem of colonial history immerses readers into eighteenth-century Boston and introduces a collection of fascinating people and intriguing circumstances” (Library Journal, starred review).

In The Fever of 1721 Stephen Coss brings to life the amazing cast of characters who changed the course of medical history, American journalism, and colonial revolution: Cotton Mather, the great Puritan preacher, son of the President of Harvard College; Zabdiel Boylston, a doctor whose name is on one of Boston’s avenues; James Franklin and his younger brother Benjamin; and Elisha Cooke and his protégé Samuel Adams.

Coss describes how, during the worst smallpox epidemic in Boston history Mather convinced Doctor Boylston to try making an incision in the arm of a healthy person and implanting it with smallpox matter. Public outrage forced Boylston into hiding and Mather’s house was firebombed.

“In 1721, Boston was a dangerous place…In Coss’s telling, the troubles of 1721 represent a shift away from a colony of faith and toward the modern politics of representative government” (The New York Times Book Review). Elisha Cooke and Samuel Adams were beginning to resist the British in the run-up to the American Revolution. Meanwhile, a bold young printer names James Franklin launched America’s first independent newspaper and landed in jail. His teenaged brother and apprentice, Benjamin Franklin, however, learned his trade in James’s shop and became a father of the Independence movement.

One by one, the atmosphere in Boston in 1721 simmered and ultimately boiled over, leading to the full drama of the American Revolution. “Fascinating, informational, and pleasing to read…Coss’s gem of colonial history immerses readers into eighteenth-century Boston and introduces a collection of fascinating people and intriguing circumstances” (Library Journal, starred review).

Excerpt

The Fever of 1721 1 IDOL OF THE MOB

For a few hours on a sunny, crisp morning in October 1716, royal governor Samuel Shute’s administration looked quite promising, at least from the outside. Salutes fired from the cannon of the town’s batteries and the guns of two British warships in the harbor alerted Boston of Shute’s imminent arrival and brought thousands of people to the waterfront for a glimpse of the first new governor in fourteen years. By the time the Lusitania docked at the end of Long Wharf a line of spectators extended the full third-of-a-mile length of the wharf and another quarter mile up King Street to the Boston Town House, where the formal welcome and swearing in would be conducted.

The man who appeared on deck, waving to his new constituents and acknowledging their cheers, had small, wide-set eyes, a puggish nose, full cheeks, and a capacious double chin that billowed like a sail over the top of his neck cloth. He was plumper and older than the war hero people had heard about, the man who had fought valiantly under Marlborough and been wounded on the battlefield in Flanders. Aside from his military credentials, all average Bostonians knew about the fifty-four-year-old retired colonel was that he had been raised a Puritan. Shute had converted to the Church of England, presumably in the interest of career advancement. But the knowledge that he shared the religious heritage of a majority of Bostonians was a comfort to those who remembered the hostility of an earlier, Puritan-hating Anglican governor who had commandeered their meetinghouses for Church of England services and had made an ostentatious show of his celebration of Christmas, a holiday Puritans not only refused to recognize but considered sacrilegious. More than anything, though, what excited the people of Boston about Samuel Shute was that he was not Joseph Dudley, his predecessor. With a new chief executive came new hope for solutions to the colony’s challenges, better cooperation between the executive and legislative branches of the colonial government, and more equitable relations with the mother country.

But many political insiders were skeptical that Samuel Shute constituted a new start, a change from the status quo. Although they, too, knew little about the man, they had discovered that his appointment had been finagled by friends of Joseph Dudley, who had first bribed the man originally appointed to replace Dudley into relinquishing the position. The mere possibility that Shute was in the pocket of Dudley and his son Paul, the colony’s attorney general, was enough to earn him enemies among his new constituents. Many persons had never forgiven Dudley for his betrayal of Massachusetts nearly three decades earlier, when he had served as henchman to the most despotic governor in the colony’s history, Edmund Andros. In 1689, the people had risen up and deposed Andros, jailing and eventually deporting him to England along with Dudley and another man, Edward Randolph. Thirteen years later the Crown had sent Dudley back to Massachusetts as its governor. Fears that he would revenge himself on his jailers with draconian assaults on individuals and group liberties had proven largely unfounded. But his administration had been both arbitrary enough and corrupt enough to spur two unsuccessful attempts to have him recalled. Having survived those, he might have remained governor for the rest of his life had Queen Anne not died prematurely at age forty-nine and her successor, George Louis, not decided to do as most new monarchs did and replace his predecessor’s appointments with men who would be in his debt. On his way out of office, Dudley had given his political opponents two final reasons to despise him, tacitly approving the scheme to rig the selection of his replacement, and double-crossing supporters of a plan to alleviate the worsening silver currency shortage by creating a private bank that would emit paper currency. After making those men believe that he would endorse the venture, he had worked secretly behind the scenes to assure its defeat.

The bank’s supporters were still smarting from that act of duplicity as the carriage carrying the man Dudley’s friends had picked to replace him made its way up King Street. In the months prior to Shute’s departure for America, Dudley’s men had thoroughly indoctrinated him in their anti-private-bank philosophy, preparing him to fend off any new attempts to launch the bank or force the government to emit paper currency. But the currency controversy was about to change in ways the new governor was unprepared to handle, evolving from a dry and somewhat tedious argument over monetary policy into a far-reaching debate over class entitlement, freedom of dissent, Americans’ liberties as Englishmen, and the colony’s right to self-determination, and becoming, as one historian put it, “the secret of political alignment” for a generation of emerging patriots and loyalists.1

SHUTE MADE TWO stops along the parade route up King Street. The first was to greet a group of the town’s ministers. The second was to meet with Joseph Dudley. That meeting took place in view of a “great Concourse of People” and a sizable group of dignitaries who had gathered at the foot of the Town House for Shute’s public welcoming ceremony.2 Those dignitaries included members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (who were known as deputies); their colleagues in the upper house, the Governor’s Council (who were known as councilors or assistants); the president of Harvard College; and numerous judges and other prominent gentlemen of the province. No one among that group was more put off by the conspicuous show of affection between the old governor and the new than the Boston representative Elisha Cooke, who had been elected to the Massachusetts House for the first time the previous year at the relatively young age of thirty-eight. Cooke came from Massachusetts political royalty: He was the grandson of John Leverett, an early governor of Massachusetts, and the son of Elisha Cooke Sr., the colony’s most influential anti-Crown politician. Cooke Sr. had been the most outspoken critic of England’s 1684 revocation of the founding Massachusetts charter, the act that had taken the power to choose its own governor away from the colony and given it to England, and one of the leaders of the 1689 uprising against Andros, the tyrant England had installed as royal governor shortly after the charter’s cancellation. He had been nearly as critical of the “New Charter” of 1691, which had restored some liberties but left with England both the power to appoint the governor and to disallow objectionable laws. Thereafter, he and members of his “Old Charter Party” had categorically opposed “royal authority over the colony and the governors’ attempts to rule by prerogative.”3 Outraged by the traitorous Joseph Dudley’s appointment as royal governor, Cooke Sr. had become his “pointed enemy.”4 The historian John Eliot wrote that Cooke Sr. “never missed the opportunity of speaking against his [Dudley’s] measures, or declaring his disapprobation of the man.”5 Right up until his death in 1715 he had also criticized Dudley’s “Prerogative Party” supporters, men who, he charged, kowtowed to the royal governor and the Crown in order to pad their fortunes or, in the case of some of the once-prominent families from the colony’s founding era, to prop up their diminishing status.

Elisha Cooke Sr. and his only son were so closely aligned politically that one detractor would describe Cooke Jr.’s contempt for English authority as a disease he had “caught” from his father.6 Indeed, he had followed his father’s example in nearly every respect. Both father and son had attended Harvard College, trained as physicians, and left the regular practice of medicine for success as businessmen. The younger Cooke’s ventures included a salt plant on Boston neck, a stake in Long Wharf (to that point the largest infrastructure project in America), and investments in Boston warehouses and taverns and in thousands of acres of prime Maine timberland. His real passion and talent, though, were for politics. Outmaneuvered by Joseph Dudley in his first foray into political dealings at the provincial level—the attempt to launch a private bank—he had nevertheless proven himself a formidable opponent. Dudley’s biographer wrote that the cagey old governor, who had survived two recalls, understood that Cooke Jr. and his bank partners represented “a faction more dangerous than any other combination he had faced.”7

With wealth, education, social standing, and a talent for public speaking—his oratory was described as “animating, energetic, concise, persuasive, and pure”—Cooke had the credentials and skills necessary to succeed as a conventional eighteenth-century politician.8 It surprised no one that within months of his election to the House he had already achieved a leadership position. But other, more unconventional talents and tactics would help him rise above conventional politicians and become the most significant and powerful Boston politician in the decades preceding the American Revolution—more hated by England than anyone but Samuel Adams (in whose political education Cooke would pay a formative role).

Shortly after their defeat of the private bank, Dudley’s Prerogative Party men had attempted to change the form of Boston’s government from the town meeting to an English-style incorporated borough system. Boston was and always had been the locus of political resistance and general incorrigibility. The town meeting, Dudley knew, fed that rebelliousness, since it gave all the people, even those without the vote, the power to speak their minds, required votes on all major issues, and mandated the yearly election of selectmen who managed town affairs. By instituting an incorporated system whereby representation came from aldermen appointed for life and vested with the power to choose a mayor, controlling the town became as simple as either arranging for the “right” men to be chosen alders or using favors and bribes to influence them. Recognizing what Dudley and his friends were up to, Cooke had published two anonymous pamphlets that declared incorporation “an oligarchic plot” by political and economic elites bent on rigging the government, the currency system, and the entire economy for their benefit.9 The pamphlets reminded rank-and-file Bostonians that each freeholder had the “undoubted right” to “speak his Opinion, and give his Advice, and Vote, too, concerning any Affair to be transacted by the Town,” and that to turn over that power to an alderman was to squander this “great Privilege their Ancestors have conveyed to them.”10 In asserting that the people were “Free-born and in bondage to no Man,” in claiming inviolable political liberties, and in rejecting the assumption that the wealthy, the powerful, the highborn, and, by extension, the royal, were superior to the average man, Cooke’s pamphlets articulated, perhaps for the first time, a distinctly and defiantly American political identity.11

The success of those pamphlets—the incorporation plan was dropped before the next opportunity to vote on it—gave credence to Cooke’s instinct for a new kind of politics. No one, not even Cooke’s father, had thought to cultivate popular support or opposition to leverage a political agenda. Most conventional politicians wouldn’t have known how to do it if they had wanted to. Cooke, though, had begun to master the art of speaking the language of the people. His classrooms were the taverns of Boston, where, by lending an ear and buying a round, he earned a reputation as not only “a drinking man without equal” but also a political leader “generous to needy people of all classes.”12 After a few rums the social and economic differences between the hardscrabble tradesmen and the wealthy Harvard man melted away, and the former saw the latter as one of their own. It helped that he looked the part. With a broad, fleshy face, full lips, jutting knob of a chin, and slight broadening at the bridge of his nose, he looked more like a workingman than an aristocrat, and more like a brawler than a fast-talking dandy. As he set about evolving his father’s Old Charter Party into what would come to be known as the Popular Party, he took every opportunity to exploit his workingman image. Eventually he would sit for his only known portrait wearing a brown periwig, the color of a tradesman. A future royal governor would sneer at his willingness to court the favor of the middling and the poor, mocking him as “the idol of the Mob.”13 But it was the support of the “mob” that would make Cooke the Crown’s most formidable threat.

HAVING REACHED THE Town House, Samuel Shute was welcomed with a brief proclamation thanking God for his safe arrival. That sentiment was punctuated by musketfire from two companies of militia. When the smoke cleared, the governor was escorted into the Town House and up the stairs to the Council chamber, where his commission was read along with that of the new lieutenant governor—Joseph Dudley’s son-in-law, William Dummer. Then both men laid their hands on the Bible and, in the words of one observer, “kiss’d it very industriously,” completing the ceremony.14 At one o’clock Shute was feted at a large, formal dinner whose guest list included his Council and “many” members of the Massachusetts House.15 After toasts had been drunk and the meal consumed, the speaker of the House turned to Shute, explained that the governor’s official residence, the Province House, was not yet ready for him, and offered him lodging in the home of William Tailer, the man who had served as interim governor between the end of Dudley’s commission and Shute’s arrival. The offer was important symbolically, since Dudley and the pro-bank Tailer had argued acrimoniously over who should occupy the governorship until Shute arrived, with each man accusing the other of trying to steal control of the colony. Tailer’s welcoming gesture reassured the people that a smooth, orderly transition of power was under way. Similarly, acceptance of the offer would send the message that although Shute was friendly with Dudley, he planned to work with both of the colony’s political factions. But much to the surprise of nearly everyone in attendance, Shute declined the offer, announcing that he had already accepted an invitation to stay with Paul Dudley, whose devotion to England’s prerogative rule of the colony eclipsed his father’s and who years earlier had infamously asserted that Massachusetts would “never be worth living in for Lawyers and Gentlemen, till the Charter is taken away.”16 In his diary that evening the conservative judge and councilor Samuel Sewall would write: “The Governour’s going to Mr. Dudley’s makes many fear that he is deliver’d up to a Party. Deus avertat Omen!” [God forbid!].17 Maybe the only man neither in on the plan nor shocked by it was Elisha Cooke, who expected no better from any man who had won endorsement by both the Crown and the Dudleys. While others had hoped that Shute’s arrival would bring a fresh start, Cooke had simply wanted an excuse to attack. And now, on his first day as governor, Shute had given him one.

ALTHOUGH ENGLAND HAD the power to appoint any governor it saw fit, a loophole in the 1691 charter had left the amount and disposition of his compensation entirely to the discretion of the Massachusetts House. The deputies had quickly capitalized on that royal oversight by declining to pay the governor a salary, as England had assumed they would, instead awarding him a biyearly “present” in whatever amount they saw fit.18 The more amenable the governor, the more money he stood to receive. This, of course, undermined England’s absolute authority over the man they placed in the position. The Crown had sent several governors to Boston with strict orders to undo the loophole. All had failed. In April 1717, Samuel Shute made his bid, calling for a fixed salary for himself and his successors. In years past it had been Elisha Cooke Sr., the man who had come up with the discretionary, nonsalary system for paying royal governors, who marshaled the House to hold firm against English pressure. Now it was his son who rounded up the votes to defeat the measure. Future efforts would prove equally futile. “In most of the royal governments,” wrote historian Timothy Pitkin, “after much difficulty, these recommendations [for fixed salaries] were finally complied with. The assembly of Massachusetts, however, could never be induced to yield . . . Thus the people of Massachusetts still continued, as in the case of the navigation acts, to claim the right of Englishmen, to grant their money when and how they pleased.”19 Shute’s peevish response to that defeat—after rejecting a House request for a new emission of paper currency (he had approved an earlier one, probably expecting that it would buy him victory in the salary vote), he shut down the General Court with important business still pending—tweaked Cooke’s indignation. Soon thereafter he made his first sidelong attack on Shute’s administration, accusing royal surveyor Jonathan Bridger of shaking down settlers in Maine (at that point a territory of Massachusetts and therefore Shute’s responsibility) for the privilege of harvesting white pines on their own land. Cooke knew that since the Lords of Trade and Plantations viewed the pines, which were ideal for ship masts, as a strategic resource, they would be irate over anything that threatened their uninterrupted supply to the Royal Navy—and that whether they blamed him or Bridger (they blamed him), they would also condemn Shute for his failure to manage the situation.

The governor and his nemesis formally became enemies on May 29, 1718, when Shute got his revenge on Cooke by exercising his right to “negative” (veto) the Popular Party leader’s elevation from the House to the Council. The negative effectively expelled Cooke from the General Court. Eight months later, Shute struck again, arranging for Cooke to be stripped of his position as clerk of the superior court. This time Shute was angry because Cooke had called him a “blockhead” while in a heated argument with one of his supporters.20

London welcomed the news of Shute’s punitive assertiveness. Rumors that he might be recalled for his failures to obtain a fixed salary and stop Cooke from harassing Jonathan Bridger faded. But in Massachusetts, where a House investigation substantiated Cooke’s claims against the royal surveyor, the governor’s vindictiveness had the opposite effect, ending his honeymoon with the people and solidifying support for Cooke, who in March 1719 was handily elected a Boston selectman for the first time. Weeks later he was elected one of the town’s four deputies to the Massachusetts House, putting him back in the General Court and in a position from which the governor had no authority to remove him. The town’s three other seats also went to men from his party. Indeed, throughout Massachusetts, the 1719 elections produced a change “unfavorable to the governor’s interest,” with the election of a majority of men philosophically aligned with Cooke and his Boston friends.21

But the size and scope of the victory were only part of the story. In Boston, Cooke had done what many had believed impossible, convincing a people so worried about vesting too much power in any one person that they almost never allowed the same man to serve as a selectman and House deputy simultaneously, to elect an identical slate of ideologically aligned candidates at both levels of government. Oliver Noyes, William Clark, and Isaiah Tay, Boston’s new House members, were all Boston selectmen. They had been elected, one correspondent wrote, “by a considerable majority, notwithstanding all endeavours used to the contrary.”22 It was a shift too seismic to have happened on its own, proof that a force was at work beneath the surface of Boston politics. Evicted from the Council, Cooke had devoted himself to expanding his base by turning Boston’s drinking establishments into “political nodes” where propaganda could be disseminated and political support nurtured with free drinks. The success of that effort was apparent in a single statistic: In Boston in 1719, the number of voters was double the average in the years from 1698 to 1717.23 Both in the town and throughout the colony, Cooke had orchestrated a dominant victory by getting out the vote, something no one before him had thought or bothered to do.

But even a man who loved rum as much as Cooke had not been able to visit every bar, make every speech, and buy every drink. To carry out his strategy, he had formed a “small clique” or “political club” that operated in semi-secrecy and that in years to come would be known as the Boston Caucus Club.24 Throughout the decades leading up to the American Revolution, “America’s first urban political ‘machine’ ” would grow and spin off new caucuses and related secret societies like the Sons of Liberty, providing the infrastructure and the leadership for the eventual all-out rebellion against Great Britain.25 No one understood its importance more than the men who headed up that effort. “Our Revolution was effected by caucuses,” wrote John Adams, a former caucus member, in 1808.26

COOKE’S POWER CAME at the price of growing threats from England. By the time the Boston lighthouse caught fire in January 1720, England had censured the Massachusetts House twice, the first time for “countenancing and encouraging” Cooke’s attacks on Bridger and again for imposing duties on imports from England.27 London reminded the House that it forbade any law that hindered English trade and warned the people of Massachusetts that they would “do well to consider, how far the breaking this condition, and the laying any discouragements on the shipping and manufactures of this Kingdome may endanger their Charter.”28 The growing anti-Massachusetts sentiment at Trade and Plantations was fed by a steady stream of accusatory letters from Surveyor Bridger. The king’s rights had never been “called into question,” wrote Bridger in one such letter, until the “Incendiary” Cooke had “endeavoured, to poyson the minds of his countreymen, with his republican notions, in order to assert the independency of New England, and claim greater privileges than ever were designed for it etc.”29 When, in May 1720, Cooke finally stood for and was elected speaker of the House, formalizing his control over that body, Bridger penned another letter. “These people,” he wrote, “will only be governed by a severe Act of Parliament w[i]th, a good penalty fixed.”30

All too aware of how Cooke-as-speaker would play in London, Samuel Shute refused to accept the vote. A standoff ensued. No one had questioned Shute’s power to negative Cooke’s earlier selection as councilor—the governor’s authority relative to the upper house was an accepted fact. But the House’s right to the speaker of its choice was nearly as sacrosanct, by tradition if not explicitly by law. Only once before had a governor refused to accept a speaker. And even in that case the governor, Joseph Dudley, had relented when two years later the same man was elected again. Now, after three days of deadlock and with no prospect of either side giving in, Shute again shut down the Court, warning in his closing remarks that Massachusetts would “suffer” if its representatives continued to insist on having Cooke as their speaker.31

Shute’s threats notwithstanding, the new elections that preceded the restart of the General Court sent mostly the same men to the House. Bostonians were particularly defiant. Voting just four days after the Boston newspapers dutifully printed Shute’s saber-rattling closing speech, they reelected the Popular Party slate of Cooke, Noyes, and William Clark. The only change in the town’s contingent was the addition of Dr. John Clark, a Popular Party member negatived from the Council by Shute at the same time he had disallowed Cooke’s speakership.

With a rematch over his selection as speaker in the offing, Cooke went on the offensive, publishing a pamphlet reminiscent of the ones that had helped defeat the attempt to incorporate the Boston government. He characterized Shute’s attempt to bar him from the speaker’s chair as an effort by England to deprive the people of Massachusetts of their rights. Employing logic and language that might have come from the pen of a Samuel Adams or James Otis a half century later, he wrote:

The happiness or infelicity of a People, intirely depending upon the enjoyment or deprivation of Libertie; Its therefore highly prudent for them to inform themselves of their just Rights, that from a due sence of their inestimable Value, they may be encouraged to assert them against the Attempts of any in time to come.32

Cooke’s rhetoric stirred his fellow House deputies. But the knowledge that Shute would again negative Cooke and shut down the session, paralyzing the government and preventing vital and already overdue measures from being enacted, eroded their resolve to insist on his speakership. On July 13, after two votes in which Cooke received a plurality of votes but not enough to again take the speaker’s chair, they elected a centrist deputy named Timothy Lindall. It was a significant win for the governor, but it came at the price of the House’s resentful belligerence. For the rest of the session the deputies voted down every proposal Shute put forward, refusing to fund the celebration of the king’s birthday, approving only a token allocation in support of Shute’s efforts to forge a diplomatic solution to the growing and “universally dreaded” Indian threat along the eastern frontier, and reducing the amount of their “grant” to the governor by £100, a cut made even larger by the stipulation that payment be made in drastically depreciated Massachusetts paper currency rather than silver.33 Shute’s reaction was a conspicuous and ominous silence. Ten tumultuous and mostly unproductive days after the session began, the governor ordered the Court closed, this time without even bothering to deliver his traditional closing remarks.

Even those who believed the colony was better off without Cooke as speaker were growing tired of Shute’s reflexive shutdowns, which suggested that he cared more about having his way than about the business of the province and the well-being of its people. Indeed, by 1721 it had come to seem that the governor viewed every setback as a personal affront requiring a retaliatory action. The opening of the General Court session that March offered the most combative version of Samuel Shute the colony had yet seen. Still angry over the slight he had received at the end of the final session of the previous year, when the deputies had awarded him the second half of his compensation for the year, again reducing it by £100 and leaving him £200 plus depreciation short of the £1,200 he had received each of the previous three years, he demanded that his salary be increased. He also demanded that the House pass a law giving him pre-publication censorship powers—which were necessary, he asserted, because of an emerging threat to his authority: a series of critical pamphlets that he termed “Factious and Scandalous” and “tending to disquiet the minds of His Majesties good Subjects.”34

There was no chance the deputies would supplement Shute’s pay. The odds that they would bow to his demand for licensing authority over the colony’s printed materials were not much better. Just over a year earlier he had tried to prevent the House from printing a harsh rebuttal to a speech in which he had blamed it for the colony’s bad reputation in London. His claim that the Crown had vested him with absolute power over the press had failed to stop the deputies from going ahead with their counterattack. Although now he had framed his request for pre-publication censorship authority as a response to threats from outside the government, the deputies knew that he would turn it against them the first time they took to print to defend their actions or criticize his.

The sudden and untimely death of Oliver Noyes, Cooke’s lieutenant and close friend, delayed the House response. The Court adjourned for several days until Noyes, who had suffered a stroke and died the following day, was buried. Perhaps because they were offended that the governor and lieutenant governor had been conspicuously absent from his funeral, the deputies came back to work more intransigent than ever. They turned down not only Shute’s demands for money and censorship authority but “directly or virtually, every proposal” he put forth during the next ten days.35 By March 31, the governor had had enough. He shut down the session with “a very sharp Speech,” admonishing the House members to “a Loyal and Peaceable Behavior” during the recess.36 The implied accusation that the deputies were about to foment some kind of mob violence or armed rebellion was ludicrous. But reading it into the official record meant it was sure to get to London, where the Lords of Trade would take it at face value and decide the Americans were even more nefarious and dangerous than they had formerly believed.

It was ironic, then, that when an act of political violence did take place the very next day it came from the governor’s nephew. John Yeamans was drinking at Richard Hall’s tavern across the street from the Town House when he got into a heated argument with another patron—his uncle’s arch-enemy Elisha Cooke. At some point Yeamans lost control and struck Cooke. A Cooke supporter named Christopher Taylor lit out after Yeamans, vowing to “have some of his blood”; when he couldn’t find him, he settled for insulting the governor, who was passing in a carriage.37 The authorities fined Yeamans for striking Cooke and Taylor for threatening Yeamans and the governor. With that, the matter was put to rest.

Within days of shutting down the assembly, Samuel Shute was off to his other government in New Hampshire. He left a colony paralyzed by acrimony and gridlock and sinking beneath the weight of its problems and threats. The Abenaki Indians had become actively hostile toward the colony’s frontier settlers, making war increasingly likely. On top of a crippling currency shortage and runaway inflation, the recent collapse of the English financial markets resulting from the bursting of the “South Sea Bubble” meant an inevitable evaporation of investments in the colony.38 And now the charter seemed doomed. It was hard to imagine how things could get worse.

For a few hours on a sunny, crisp morning in October 1716, royal governor Samuel Shute’s administration looked quite promising, at least from the outside. Salutes fired from the cannon of the town’s batteries and the guns of two British warships in the harbor alerted Boston of Shute’s imminent arrival and brought thousands of people to the waterfront for a glimpse of the first new governor in fourteen years. By the time the Lusitania docked at the end of Long Wharf a line of spectators extended the full third-of-a-mile length of the wharf and another quarter mile up King Street to the Boston Town House, where the formal welcome and swearing in would be conducted.

The man who appeared on deck, waving to his new constituents and acknowledging their cheers, had small, wide-set eyes, a puggish nose, full cheeks, and a capacious double chin that billowed like a sail over the top of his neck cloth. He was plumper and older than the war hero people had heard about, the man who had fought valiantly under Marlborough and been wounded on the battlefield in Flanders. Aside from his military credentials, all average Bostonians knew about the fifty-four-year-old retired colonel was that he had been raised a Puritan. Shute had converted to the Church of England, presumably in the interest of career advancement. But the knowledge that he shared the religious heritage of a majority of Bostonians was a comfort to those who remembered the hostility of an earlier, Puritan-hating Anglican governor who had commandeered their meetinghouses for Church of England services and had made an ostentatious show of his celebration of Christmas, a holiday Puritans not only refused to recognize but considered sacrilegious. More than anything, though, what excited the people of Boston about Samuel Shute was that he was not Joseph Dudley, his predecessor. With a new chief executive came new hope for solutions to the colony’s challenges, better cooperation between the executive and legislative branches of the colonial government, and more equitable relations with the mother country.

But many political insiders were skeptical that Samuel Shute constituted a new start, a change from the status quo. Although they, too, knew little about the man, they had discovered that his appointment had been finagled by friends of Joseph Dudley, who had first bribed the man originally appointed to replace Dudley into relinquishing the position. The mere possibility that Shute was in the pocket of Dudley and his son Paul, the colony’s attorney general, was enough to earn him enemies among his new constituents. Many persons had never forgiven Dudley for his betrayal of Massachusetts nearly three decades earlier, when he had served as henchman to the most despotic governor in the colony’s history, Edmund Andros. In 1689, the people had risen up and deposed Andros, jailing and eventually deporting him to England along with Dudley and another man, Edward Randolph. Thirteen years later the Crown had sent Dudley back to Massachusetts as its governor. Fears that he would revenge himself on his jailers with draconian assaults on individuals and group liberties had proven largely unfounded. But his administration had been both arbitrary enough and corrupt enough to spur two unsuccessful attempts to have him recalled. Having survived those, he might have remained governor for the rest of his life had Queen Anne not died prematurely at age forty-nine and her successor, George Louis, not decided to do as most new monarchs did and replace his predecessor’s appointments with men who would be in his debt. On his way out of office, Dudley had given his political opponents two final reasons to despise him, tacitly approving the scheme to rig the selection of his replacement, and double-crossing supporters of a plan to alleviate the worsening silver currency shortage by creating a private bank that would emit paper currency. After making those men believe that he would endorse the venture, he had worked secretly behind the scenes to assure its defeat.

The bank’s supporters were still smarting from that act of duplicity as the carriage carrying the man Dudley’s friends had picked to replace him made its way up King Street. In the months prior to Shute’s departure for America, Dudley’s men had thoroughly indoctrinated him in their anti-private-bank philosophy, preparing him to fend off any new attempts to launch the bank or force the government to emit paper currency. But the currency controversy was about to change in ways the new governor was unprepared to handle, evolving from a dry and somewhat tedious argument over monetary policy into a far-reaching debate over class entitlement, freedom of dissent, Americans’ liberties as Englishmen, and the colony’s right to self-determination, and becoming, as one historian put it, “the secret of political alignment” for a generation of emerging patriots and loyalists.1

SHUTE MADE TWO stops along the parade route up King Street. The first was to greet a group of the town’s ministers. The second was to meet with Joseph Dudley. That meeting took place in view of a “great Concourse of People” and a sizable group of dignitaries who had gathered at the foot of the Town House for Shute’s public welcoming ceremony.2 Those dignitaries included members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (who were known as deputies); their colleagues in the upper house, the Governor’s Council (who were known as councilors or assistants); the president of Harvard College; and numerous judges and other prominent gentlemen of the province. No one among that group was more put off by the conspicuous show of affection between the old governor and the new than the Boston representative Elisha Cooke, who had been elected to the Massachusetts House for the first time the previous year at the relatively young age of thirty-eight. Cooke came from Massachusetts political royalty: He was the grandson of John Leverett, an early governor of Massachusetts, and the son of Elisha Cooke Sr., the colony’s most influential anti-Crown politician. Cooke Sr. had been the most outspoken critic of England’s 1684 revocation of the founding Massachusetts charter, the act that had taken the power to choose its own governor away from the colony and given it to England, and one of the leaders of the 1689 uprising against Andros, the tyrant England had installed as royal governor shortly after the charter’s cancellation. He had been nearly as critical of the “New Charter” of 1691, which had restored some liberties but left with England both the power to appoint the governor and to disallow objectionable laws. Thereafter, he and members of his “Old Charter Party” had categorically opposed “royal authority over the colony and the governors’ attempts to rule by prerogative.”3 Outraged by the traitorous Joseph Dudley’s appointment as royal governor, Cooke Sr. had become his “pointed enemy.”4 The historian John Eliot wrote that Cooke Sr. “never missed the opportunity of speaking against his [Dudley’s] measures, or declaring his disapprobation of the man.”5 Right up until his death in 1715 he had also criticized Dudley’s “Prerogative Party” supporters, men who, he charged, kowtowed to the royal governor and the Crown in order to pad their fortunes or, in the case of some of the once-prominent families from the colony’s founding era, to prop up their diminishing status.

Elisha Cooke Sr. and his only son were so closely aligned politically that one detractor would describe Cooke Jr.’s contempt for English authority as a disease he had “caught” from his father.6 Indeed, he had followed his father’s example in nearly every respect. Both father and son had attended Harvard College, trained as physicians, and left the regular practice of medicine for success as businessmen. The younger Cooke’s ventures included a salt plant on Boston neck, a stake in Long Wharf (to that point the largest infrastructure project in America), and investments in Boston warehouses and taverns and in thousands of acres of prime Maine timberland. His real passion and talent, though, were for politics. Outmaneuvered by Joseph Dudley in his first foray into political dealings at the provincial level—the attempt to launch a private bank—he had nevertheless proven himself a formidable opponent. Dudley’s biographer wrote that the cagey old governor, who had survived two recalls, understood that Cooke Jr. and his bank partners represented “a faction more dangerous than any other combination he had faced.”7

With wealth, education, social standing, and a talent for public speaking—his oratory was described as “animating, energetic, concise, persuasive, and pure”—Cooke had the credentials and skills necessary to succeed as a conventional eighteenth-century politician.8 It surprised no one that within months of his election to the House he had already achieved a leadership position. But other, more unconventional talents and tactics would help him rise above conventional politicians and become the most significant and powerful Boston politician in the decades preceding the American Revolution—more hated by England than anyone but Samuel Adams (in whose political education Cooke would pay a formative role).

Shortly after their defeat of the private bank, Dudley’s Prerogative Party men had attempted to change the form of Boston’s government from the town meeting to an English-style incorporated borough system. Boston was and always had been the locus of political resistance and general incorrigibility. The town meeting, Dudley knew, fed that rebelliousness, since it gave all the people, even those without the vote, the power to speak their minds, required votes on all major issues, and mandated the yearly election of selectmen who managed town affairs. By instituting an incorporated system whereby representation came from aldermen appointed for life and vested with the power to choose a mayor, controlling the town became as simple as either arranging for the “right” men to be chosen alders or using favors and bribes to influence them. Recognizing what Dudley and his friends were up to, Cooke had published two anonymous pamphlets that declared incorporation “an oligarchic plot” by political and economic elites bent on rigging the government, the currency system, and the entire economy for their benefit.9 The pamphlets reminded rank-and-file Bostonians that each freeholder had the “undoubted right” to “speak his Opinion, and give his Advice, and Vote, too, concerning any Affair to be transacted by the Town,” and that to turn over that power to an alderman was to squander this “great Privilege their Ancestors have conveyed to them.”10 In asserting that the people were “Free-born and in bondage to no Man,” in claiming inviolable political liberties, and in rejecting the assumption that the wealthy, the powerful, the highborn, and, by extension, the royal, were superior to the average man, Cooke’s pamphlets articulated, perhaps for the first time, a distinctly and defiantly American political identity.11

The success of those pamphlets—the incorporation plan was dropped before the next opportunity to vote on it—gave credence to Cooke’s instinct for a new kind of politics. No one, not even Cooke’s father, had thought to cultivate popular support or opposition to leverage a political agenda. Most conventional politicians wouldn’t have known how to do it if they had wanted to. Cooke, though, had begun to master the art of speaking the language of the people. His classrooms were the taverns of Boston, where, by lending an ear and buying a round, he earned a reputation as not only “a drinking man without equal” but also a political leader “generous to needy people of all classes.”12 After a few rums the social and economic differences between the hardscrabble tradesmen and the wealthy Harvard man melted away, and the former saw the latter as one of their own. It helped that he looked the part. With a broad, fleshy face, full lips, jutting knob of a chin, and slight broadening at the bridge of his nose, he looked more like a workingman than an aristocrat, and more like a brawler than a fast-talking dandy. As he set about evolving his father’s Old Charter Party into what would come to be known as the Popular Party, he took every opportunity to exploit his workingman image. Eventually he would sit for his only known portrait wearing a brown periwig, the color of a tradesman. A future royal governor would sneer at his willingness to court the favor of the middling and the poor, mocking him as “the idol of the Mob.”13 But it was the support of the “mob” that would make Cooke the Crown’s most formidable threat.

HAVING REACHED THE Town House, Samuel Shute was welcomed with a brief proclamation thanking God for his safe arrival. That sentiment was punctuated by musketfire from two companies of militia. When the smoke cleared, the governor was escorted into the Town House and up the stairs to the Council chamber, where his commission was read along with that of the new lieutenant governor—Joseph Dudley’s son-in-law, William Dummer. Then both men laid their hands on the Bible and, in the words of one observer, “kiss’d it very industriously,” completing the ceremony.14 At one o’clock Shute was feted at a large, formal dinner whose guest list included his Council and “many” members of the Massachusetts House.15 After toasts had been drunk and the meal consumed, the speaker of the House turned to Shute, explained that the governor’s official residence, the Province House, was not yet ready for him, and offered him lodging in the home of William Tailer, the man who had served as interim governor between the end of Dudley’s commission and Shute’s arrival. The offer was important symbolically, since Dudley and the pro-bank Tailer had argued acrimoniously over who should occupy the governorship until Shute arrived, with each man accusing the other of trying to steal control of the colony. Tailer’s welcoming gesture reassured the people that a smooth, orderly transition of power was under way. Similarly, acceptance of the offer would send the message that although Shute was friendly with Dudley, he planned to work with both of the colony’s political factions. But much to the surprise of nearly everyone in attendance, Shute declined the offer, announcing that he had already accepted an invitation to stay with Paul Dudley, whose devotion to England’s prerogative rule of the colony eclipsed his father’s and who years earlier had infamously asserted that Massachusetts would “never be worth living in for Lawyers and Gentlemen, till the Charter is taken away.”16 In his diary that evening the conservative judge and councilor Samuel Sewall would write: “The Governour’s going to Mr. Dudley’s makes many fear that he is deliver’d up to a Party. Deus avertat Omen!” [God forbid!].17 Maybe the only man neither in on the plan nor shocked by it was Elisha Cooke, who expected no better from any man who had won endorsement by both the Crown and the Dudleys. While others had hoped that Shute’s arrival would bring a fresh start, Cooke had simply wanted an excuse to attack. And now, on his first day as governor, Shute had given him one.

ALTHOUGH ENGLAND HAD the power to appoint any governor it saw fit, a loophole in the 1691 charter had left the amount and disposition of his compensation entirely to the discretion of the Massachusetts House. The deputies had quickly capitalized on that royal oversight by declining to pay the governor a salary, as England had assumed they would, instead awarding him a biyearly “present” in whatever amount they saw fit.18 The more amenable the governor, the more money he stood to receive. This, of course, undermined England’s absolute authority over the man they placed in the position. The Crown had sent several governors to Boston with strict orders to undo the loophole. All had failed. In April 1717, Samuel Shute made his bid, calling for a fixed salary for himself and his successors. In years past it had been Elisha Cooke Sr., the man who had come up with the discretionary, nonsalary system for paying royal governors, who marshaled the House to hold firm against English pressure. Now it was his son who rounded up the votes to defeat the measure. Future efforts would prove equally futile. “In most of the royal governments,” wrote historian Timothy Pitkin, “after much difficulty, these recommendations [for fixed salaries] were finally complied with. The assembly of Massachusetts, however, could never be induced to yield . . . Thus the people of Massachusetts still continued, as in the case of the navigation acts, to claim the right of Englishmen, to grant their money when and how they pleased.”19 Shute’s peevish response to that defeat—after rejecting a House request for a new emission of paper currency (he had approved an earlier one, probably expecting that it would buy him victory in the salary vote), he shut down the General Court with important business still pending—tweaked Cooke’s indignation. Soon thereafter he made his first sidelong attack on Shute’s administration, accusing royal surveyor Jonathan Bridger of shaking down settlers in Maine (at that point a territory of Massachusetts and therefore Shute’s responsibility) for the privilege of harvesting white pines on their own land. Cooke knew that since the Lords of Trade and Plantations viewed the pines, which were ideal for ship masts, as a strategic resource, they would be irate over anything that threatened their uninterrupted supply to the Royal Navy—and that whether they blamed him or Bridger (they blamed him), they would also condemn Shute for his failure to manage the situation.

The governor and his nemesis formally became enemies on May 29, 1718, when Shute got his revenge on Cooke by exercising his right to “negative” (veto) the Popular Party leader’s elevation from the House to the Council. The negative effectively expelled Cooke from the General Court. Eight months later, Shute struck again, arranging for Cooke to be stripped of his position as clerk of the superior court. This time Shute was angry because Cooke had called him a “blockhead” while in a heated argument with one of his supporters.20

London welcomed the news of Shute’s punitive assertiveness. Rumors that he might be recalled for his failures to obtain a fixed salary and stop Cooke from harassing Jonathan Bridger faded. But in Massachusetts, where a House investigation substantiated Cooke’s claims against the royal surveyor, the governor’s vindictiveness had the opposite effect, ending his honeymoon with the people and solidifying support for Cooke, who in March 1719 was handily elected a Boston selectman for the first time. Weeks later he was elected one of the town’s four deputies to the Massachusetts House, putting him back in the General Court and in a position from which the governor had no authority to remove him. The town’s three other seats also went to men from his party. Indeed, throughout Massachusetts, the 1719 elections produced a change “unfavorable to the governor’s interest,” with the election of a majority of men philosophically aligned with Cooke and his Boston friends.21

But the size and scope of the victory were only part of the story. In Boston, Cooke had done what many had believed impossible, convincing a people so worried about vesting too much power in any one person that they almost never allowed the same man to serve as a selectman and House deputy simultaneously, to elect an identical slate of ideologically aligned candidates at both levels of government. Oliver Noyes, William Clark, and Isaiah Tay, Boston’s new House members, were all Boston selectmen. They had been elected, one correspondent wrote, “by a considerable majority, notwithstanding all endeavours used to the contrary.”22 It was a shift too seismic to have happened on its own, proof that a force was at work beneath the surface of Boston politics. Evicted from the Council, Cooke had devoted himself to expanding his base by turning Boston’s drinking establishments into “political nodes” where propaganda could be disseminated and political support nurtured with free drinks. The success of that effort was apparent in a single statistic: In Boston in 1719, the number of voters was double the average in the years from 1698 to 1717.23 Both in the town and throughout the colony, Cooke had orchestrated a dominant victory by getting out the vote, something no one before him had thought or bothered to do.

But even a man who loved rum as much as Cooke had not been able to visit every bar, make every speech, and buy every drink. To carry out his strategy, he had formed a “small clique” or “political club” that operated in semi-secrecy and that in years to come would be known as the Boston Caucus Club.24 Throughout the decades leading up to the American Revolution, “America’s first urban political ‘machine’ ” would grow and spin off new caucuses and related secret societies like the Sons of Liberty, providing the infrastructure and the leadership for the eventual all-out rebellion against Great Britain.25 No one understood its importance more than the men who headed up that effort. “Our Revolution was effected by caucuses,” wrote John Adams, a former caucus member, in 1808.26

COOKE’S POWER CAME at the price of growing threats from England. By the time the Boston lighthouse caught fire in January 1720, England had censured the Massachusetts House twice, the first time for “countenancing and encouraging” Cooke’s attacks on Bridger and again for imposing duties on imports from England.27 London reminded the House that it forbade any law that hindered English trade and warned the people of Massachusetts that they would “do well to consider, how far the breaking this condition, and the laying any discouragements on the shipping and manufactures of this Kingdome may endanger their Charter.”28 The growing anti-Massachusetts sentiment at Trade and Plantations was fed by a steady stream of accusatory letters from Surveyor Bridger. The king’s rights had never been “called into question,” wrote Bridger in one such letter, until the “Incendiary” Cooke had “endeavoured, to poyson the minds of his countreymen, with his republican notions, in order to assert the independency of New England, and claim greater privileges than ever were designed for it etc.”29 When, in May 1720, Cooke finally stood for and was elected speaker of the House, formalizing his control over that body, Bridger penned another letter. “These people,” he wrote, “will only be governed by a severe Act of Parliament w[i]th, a good penalty fixed.”30

All too aware of how Cooke-as-speaker would play in London, Samuel Shute refused to accept the vote. A standoff ensued. No one had questioned Shute’s power to negative Cooke’s earlier selection as councilor—the governor’s authority relative to the upper house was an accepted fact. But the House’s right to the speaker of its choice was nearly as sacrosanct, by tradition if not explicitly by law. Only once before had a governor refused to accept a speaker. And even in that case the governor, Joseph Dudley, had relented when two years later the same man was elected again. Now, after three days of deadlock and with no prospect of either side giving in, Shute again shut down the Court, warning in his closing remarks that Massachusetts would “suffer” if its representatives continued to insist on having Cooke as their speaker.31

Shute’s threats notwithstanding, the new elections that preceded the restart of the General Court sent mostly the same men to the House. Bostonians were particularly defiant. Voting just four days after the Boston newspapers dutifully printed Shute’s saber-rattling closing speech, they reelected the Popular Party slate of Cooke, Noyes, and William Clark. The only change in the town’s contingent was the addition of Dr. John Clark, a Popular Party member negatived from the Council by Shute at the same time he had disallowed Cooke’s speakership.

With a rematch over his selection as speaker in the offing, Cooke went on the offensive, publishing a pamphlet reminiscent of the ones that had helped defeat the attempt to incorporate the Boston government. He characterized Shute’s attempt to bar him from the speaker’s chair as an effort by England to deprive the people of Massachusetts of their rights. Employing logic and language that might have come from the pen of a Samuel Adams or James Otis a half century later, he wrote:

The happiness or infelicity of a People, intirely depending upon the enjoyment or deprivation of Libertie; Its therefore highly prudent for them to inform themselves of their just Rights, that from a due sence of their inestimable Value, they may be encouraged to assert them against the Attempts of any in time to come.32

Cooke’s rhetoric stirred his fellow House deputies. But the knowledge that Shute would again negative Cooke and shut down the session, paralyzing the government and preventing vital and already overdue measures from being enacted, eroded their resolve to insist on his speakership. On July 13, after two votes in which Cooke received a plurality of votes but not enough to again take the speaker’s chair, they elected a centrist deputy named Timothy Lindall. It was a significant win for the governor, but it came at the price of the House’s resentful belligerence. For the rest of the session the deputies voted down every proposal Shute put forward, refusing to fund the celebration of the king’s birthday, approving only a token allocation in support of Shute’s efforts to forge a diplomatic solution to the growing and “universally dreaded” Indian threat along the eastern frontier, and reducing the amount of their “grant” to the governor by £100, a cut made even larger by the stipulation that payment be made in drastically depreciated Massachusetts paper currency rather than silver.33 Shute’s reaction was a conspicuous and ominous silence. Ten tumultuous and mostly unproductive days after the session began, the governor ordered the Court closed, this time without even bothering to deliver his traditional closing remarks.

Even those who believed the colony was better off without Cooke as speaker were growing tired of Shute’s reflexive shutdowns, which suggested that he cared more about having his way than about the business of the province and the well-being of its people. Indeed, by 1721 it had come to seem that the governor viewed every setback as a personal affront requiring a retaliatory action. The opening of the General Court session that March offered the most combative version of Samuel Shute the colony had yet seen. Still angry over the slight he had received at the end of the final session of the previous year, when the deputies had awarded him the second half of his compensation for the year, again reducing it by £100 and leaving him £200 plus depreciation short of the £1,200 he had received each of the previous three years, he demanded that his salary be increased. He also demanded that the House pass a law giving him pre-publication censorship powers—which were necessary, he asserted, because of an emerging threat to his authority: a series of critical pamphlets that he termed “Factious and Scandalous” and “tending to disquiet the minds of His Majesties good Subjects.”34

There was no chance the deputies would supplement Shute’s pay. The odds that they would bow to his demand for licensing authority over the colony’s printed materials were not much better. Just over a year earlier he had tried to prevent the House from printing a harsh rebuttal to a speech in which he had blamed it for the colony’s bad reputation in London. His claim that the Crown had vested him with absolute power over the press had failed to stop the deputies from going ahead with their counterattack. Although now he had framed his request for pre-publication censorship authority as a response to threats from outside the government, the deputies knew that he would turn it against them the first time they took to print to defend their actions or criticize his.

The sudden and untimely death of Oliver Noyes, Cooke’s lieutenant and close friend, delayed the House response. The Court adjourned for several days until Noyes, who had suffered a stroke and died the following day, was buried. Perhaps because they were offended that the governor and lieutenant governor had been conspicuously absent from his funeral, the deputies came back to work more intransigent than ever. They turned down not only Shute’s demands for money and censorship authority but “directly or virtually, every proposal” he put forth during the next ten days.35 By March 31, the governor had had enough. He shut down the session with “a very sharp Speech,” admonishing the House members to “a Loyal and Peaceable Behavior” during the recess.36 The implied accusation that the deputies were about to foment some kind of mob violence or armed rebellion was ludicrous. But reading it into the official record meant it was sure to get to London, where the Lords of Trade would take it at face value and decide the Americans were even more nefarious and dangerous than they had formerly believed.

It was ironic, then, that when an act of political violence did take place the very next day it came from the governor’s nephew. John Yeamans was drinking at Richard Hall’s tavern across the street from the Town House when he got into a heated argument with another patron—his uncle’s arch-enemy Elisha Cooke. At some point Yeamans lost control and struck Cooke. A Cooke supporter named Christopher Taylor lit out after Yeamans, vowing to “have some of his blood”; when he couldn’t find him, he settled for insulting the governor, who was passing in a carriage.37 The authorities fined Yeamans for striking Cooke and Taylor for threatening Yeamans and the governor. With that, the matter was put to rest.

Within days of shutting down the assembly, Samuel Shute was off to his other government in New Hampshire. He left a colony paralyzed by acrimony and gridlock and sinking beneath the weight of its problems and threats. The Abenaki Indians had become actively hostile toward the colony’s frontier settlers, making war increasingly likely. On top of a crippling currency shortage and runaway inflation, the recent collapse of the English financial markets resulting from the bursting of the “South Sea Bubble” meant an inevitable evaporation of investments in the colony.38 And now the charter seemed doomed. It was hard to imagine how things could get worse.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (March 28, 2017)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476783116

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Fever of 1721 Trade Paperback 9781476783116

- Author Photo (jpg): Stephen Coss Photograph by Judy Fleming Coss(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit