Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

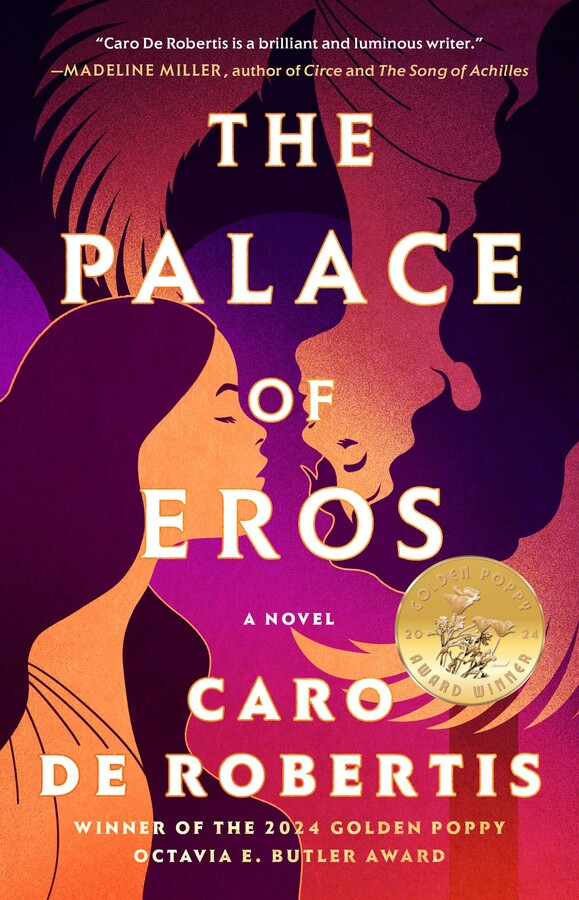

“It’s a literary gift to see gender expansiveness depicted in an ancient myth with such grace and ease.” —Electric Literature

Fans of Circe and Black Sun, “prepare to be astonished” (R.O. Kwon, author of The Incendiaries) with this bold and subversive feminist and queer retelling of the Greek myth of Psyche and Eros.

Young, headstrong Psyche has captured the eyes of every suitor in town with her tempestuous beauty, which has made her irresistible as a woman yet undesirable as a wife. Secretly, she longs for a life away from the expectations of men. When her father realizes that the future of his family and town will be forever cursed unless he appeases an enraged Aphrodite, he follows the orders of the Oracle, tying Psyche to a rock to be ravaged by a monstrous husband. And yet a monster never arrives.

When Eros, nonbinary deity of desire, sees Psyche, she cannot fulfill her promise to her mother Aphrodite to destroy the mortal young woman. Instead, Eros devises a plan to sweep Psyche away to a palace, hidden from the prying eyes of the gods and outside world. There, Eros and Psyche fall in love. Each night, Eros visits Psyche under the cover of impenetrable darkness, where they both experience untold passion and love. But each morning, Eros flies away before light comes to break the spell of the palace that keeps them safe.

Before long, Psyche’s nights spent in pleasure turn to days filled with doubts, as she grapples with the cost of secrecy and the complexities of freedom and desire. Restless and spurred by her sisters to reveal Eros’s true nature, she breaks her trust and forces a reckoning that tests them both—and transforms the very heavens in this “brilliant and luminous” (Madeline Miller, New York Times bestselling author) epic.

Fans of Circe and Black Sun, “prepare to be astonished” (R.O. Kwon, author of The Incendiaries) with this bold and subversive feminist and queer retelling of the Greek myth of Psyche and Eros.

Young, headstrong Psyche has captured the eyes of every suitor in town with her tempestuous beauty, which has made her irresistible as a woman yet undesirable as a wife. Secretly, she longs for a life away from the expectations of men. When her father realizes that the future of his family and town will be forever cursed unless he appeases an enraged Aphrodite, he follows the orders of the Oracle, tying Psyche to a rock to be ravaged by a monstrous husband. And yet a monster never arrives.

When Eros, nonbinary deity of desire, sees Psyche, she cannot fulfill her promise to her mother Aphrodite to destroy the mortal young woman. Instead, Eros devises a plan to sweep Psyche away to a palace, hidden from the prying eyes of the gods and outside world. There, Eros and Psyche fall in love. Each night, Eros visits Psyche under the cover of impenetrable darkness, where they both experience untold passion and love. But each morning, Eros flies away before light comes to break the spell of the palace that keeps them safe.

Before long, Psyche’s nights spent in pleasure turn to days filled with doubts, as she grapples with the cost of secrecy and the complexities of freedom and desire. Restless and spurred by her sisters to reveal Eros’s true nature, she breaks her trust and forces a reckoning that tests them both—and transforms the very heavens in this “brilliant and luminous” (Madeline Miller, New York Times bestselling author) epic.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1

I arrived at her palace by soaring from a rock where I’d been left for dead. How I came to be on that rock is not the core of my story, but it’s where I’ll begin—for all stories have roots, as plants do, as people do. As legends do. In the case of legends, too much distance from the root can twist the tale into a lie. Think of the hordes who want it that way, who obscure on purpose. You’ve seen it, haven’t you? The way they balk at a story with too many sharp edges or unfamiliar colors? How bards and gossips warp a tale to their will? I know why they do it, the allure of audience delight. The trouble comes when feeding that delight means flattening out what gives a story life and power, its wilder shapes, the jagged or the billowed, the spike and fall of songs usually buried under silence. There are truths that some don’t want to hear. Without those truths, stories lose their teeth. Limbs. Bones. It’s safer that way, for gossips and bards. Which is why I don’t trust them when it comes to my story with Eros, the story of Eros and me.

I wouldn’t trust them either if I were you.

Sit closer. Let me give you my telling, starting at the root.

According to my mother, I arrived in the last hour before sunrise, so fast the village healer didn’t come in time and instead I fell into the trembling hands of a kitchen maid. You burned, my mother said, like an arrow made of sunlight, as if you could shoot through me, as if you’d turned my flesh to air, that’s how you flew into the world. Insistent, you were. You wept that night as if you missed the motion. You were not quiet like your sisters when they were born. This frightened me, so I sang you an old song about the earth, to help you land here, my love, my dear Psyche. To blunt the longing. Girls need that.

“To be close to the earth?” I asked.

“To stop dreaming of flight.”

I was five then and entranced by the rare thrill of a walk alone with my mother as we carried the washing from the river. The story landed in me like a welcome stone, forming ripples I was still too young to understand.

Later I’d know.

About flight, and girls, and dreaming. How a body can be arrow, can be air, can burn.

When the men came, my world shattered—but before that, I was unafraid, and I knew joy. I will tell that, too, for I want you to have the whole story, a story as whole as I can weave in language not made to hold these truths, not made for me, or you. Perhaps you’ll know the feeling, and the limitations of my speaking won’t matter, you’ll understand. Perhaps you too recall a time when you were small and the days gleamed with secret light, as if the walls and bowls and stones and river and leaves each caught the sun inside them and shivered with the glow of their own being. I was completely alive inside. I was still free. Joy hid everywhere. In the scent of grass and dirt when I lay on the ground. In the feel of heat on my skin on summer days, and the whip of cold in winter. In the rush of the river around me when I bathed there, a living aqueous body surrounding mine. In the way a tree could subsume me, swallow my shadow into its own like water poured to water, blending dark with dark, a recognition and a coming home. In the ease of sinking my body into the cool scope of a tree, oak or olive, fig or pine, blended into them, until I felt my roots deep in the earth below and my head green with leaves reaching greedily up to the sun. In the rich murmur of rain against our roof, spilling tales from the heavens, a wet weeping and laughter of secrets I longed to translate or swim into with my human mind. I could stay up all night listening to the language of the rain. I dreamed I could be rain, sky, river, tree. I dreamed I could be melted by my love for the world. Poured and blended. Lost, remade.

These were silent journeys, utterly private. I never spoke of them to anyone. When I was very small, I thought everyone lived this way inside, in a constant connection to infinity. Including my sisters. Though in the end, it was my sisters who showed me how wrong I was to imagine that everyone was like me. Theirs was a different way of moving through the world. It was often my sisters who called me back from the dream-space, into the task at hand. Psyche, what are you doing, you’re distracted again, what’s the matter with you, hurry up, the dark is coming soon!

They were ever-present as the air itself, my sisters, Iantha and Coronis, Coronis and Iantha. Elegant and limber as the saplings that rise at the river’s shore. They towered over me; they interrupted my reveries but also brought shape and life to my days. These two tall girls who knew things I did not, who were older than me. I watched them in a kind of enchanted awe.

Iantha was the eldest, sharp-witted, always the first to know things: when a goat was about to give birth, which river rocks made the best stepping stones, how to stitch fast without stabbing your own fingers, when the traveling merchants had arrived in the village with ribbons and spices and thread. She had a laugh capable of reducing a person to the size of a mushroom, or warming the hardest stone. I feared that laugh and pined to hear it. Her presence woke me and yet dwarfed me, all at once. I wanted to be near her; I was nurtured by her shadow.

Coronis was the middle sister, the most fair. Her hair was the color of threshed wheat, though she preferred to hear it called the color of the sun. She could not match our elder sister in wits, but made up for it in charm, for she moved with a dancing grace even when picking figs or scrubbing pots, and when we were small it was she who had the reputation as a beauty bound to steal the hearts of men and earn her a place beside a king.

The two of them often kept their thoughts to themselves or to the tightly sealed container of their bond. With a quick glance they could enact a whole conversation that was impossible for me to decipher. They were inseparable even when they quarreled, even when they would not direct a word to each other. They’d learned to read each other’s thoughts before I was born; they saw no need to slow down their secret language so I could understand. I had the constant feeling that my older sisters held—in their palms, their thoughts, their voices—the keys to the world. I wanted to see or hear the glint of what they knew, what they shared with each other.

I’d follow them around as they played their games and did their spinning and weaving, or washed their clothes at the river. I often struggled to keep up with them on my shorter legs, and well they knew it, for they laughed at the sight of me loping out of breath to catch up with them in the forest, though at other times they’d help me through brambles or across the stream with its stepping stones. I was always determined to stay close and hear every word they exchanged, no matter the subject, as they whispered or chatted or howled: what they thought about this or that boy they’d glimpsed at a distance in the village; the meaning of a tale they’d heard the servants murmur at the fire; how to oil their hair so it shone as if lit from within.

When they oiled their hair, I watched them studiously, then snuck some of the unguent to try, hoping it might seep into my scalp and unlock some special powers in my mind, though all it got me was a scolding when I was discovered. Psyche! You’re too small for that! Look at the mess you’ve made! And only then did I see the slick puddle on the floor. I’d been so eager to reach for the bottle, entranced by olive oil, the way it made my fingers gleam and slide against each other, that I hadn’t noticed the spill. Messy Psyche. Wild, impulsive Psyche. As my sisters braided their hair—as well as mine, with calm, steady hands whose touch I relished—they talked their future husbands into being. My hair was the darkest among the three, a deep black punctuated by slender strands the shade of fertile soil. Secretly, I loved my hair, the only part of me that inspired a private—what? Not vanity, exactly, so much as a sumptuousness, a sensual joy in my own self, though of course I knew better than to breathe a word of it to anyone, how I liked to run my fingers through its richness when no one was looking, how the swing of braids against my body pleased me, how I loved that my hair took after our mother’s own black curls.

For I was dark like my mother, like the people of this valley before the Greek ships came. My mother’s mother was born three years before the Greeks arrived, with their spears and swords and insistence on claiming the land. They claimed the women, too, and the girls, especially the girls. I know little about my grandmother. I’ve pieced together her story from scraps of telling, dropped by my mother in the women’s room on long afternoons in a voice so quiet you had to lean in close to catch the words. I know my grandmother remembered her own mother weeping in the corner of the kitchen, curled into a ball behind a curtain of her loose black hair, because her husband had disappeared. The disappearance was never explained to my three-year-old grandmother beyond the words he is gone, which her mother repeated like a hymn or curse. There was no body, no blood, no funeral pyre, no tracks to where he might have fled, no speaking of his story or his name. Only an absence, soon filled by a Greek merchant who took my great-grandmother as his wife. She bore him more children. The children from before, like my grandmother, grew up careful to serve and obey and stay in their stepfather’s good graces, for their fate was now in his hands.

When my grandmother was fourteen, she was married off to a much older man who’d recently come from Greece. This was Iloneus, my grandfather. He established a farm across the mountains that ring our valley, happy to finally claim his own patch of earth, a far more fertile place than the rocky crags from which he’d sailed on his ship of hungry men, or so he told his children. My mother was among those children, listening quietly as she refilled his wine. She grew up speaking only Greek, for her father, Iloneus, forbade the old language from the home. It came to her only in music. Her mother hummed as she wove, sang softly in the night, soothed children with tunes when no one else could hear. Those are the songs my mother gave us when we were small, which enfolded my sisters and me, like the one she crooned when I was born. Old songs. In the old language, the language of the land, she sometimes called it. The melodies flowed like a stream over dark stones. Sounds unmade of meaning, unclasped from thought or time. Sounds that carried what could not be spoken, soul to throat to ear to soul. I didn’t learn the songs, but they settled in me, deep inside me and yet absent at the same time.

My mother was both Greek and something else, and the something else carried on in my olive skin and thick black hair. Not all the Greeks were pale and fair-haired, but our father was, and Coronis took after him, while Iantha was a blend of the two, her hair a medium brown, her skin tone somewhere between Coronis’s and mine. Both of my sisters took pride in their lighter locks and the rarity of their hazel eyes. They believed this would give them an advantage in the future, especially fair Coronis. It was not only vanity that made them think so, for everyone believed it, including my mother, who was the most beautiful woman I could ever have imagined yet who believed the daughters who were lighter than her stood the stronger chance with suitors. Nobody saw the future coming. Not one of us could have glimpsed it even in a dream.

“They will fall on their knees for us,” Iantha would say, tugging slightly too hard on a rope of my hair, braiding with efficient flicks.

Coronis smirked. “Especially for me.”

“Hmmf! Perhaps.” Iantha sounded grudging. “But I’ll make up for it with my wit; I’ll charm them with my stories. Sit still, Psyche.”

“Sorry.” I stopped my fidgeting so their talk would carry on.

“Ah, Iantha!” Coronis batted her playfully. “On what cloud are you? You think suitors want to hear a girl talk?”

They laughed, together. I laughed along, tentative, uncertain.

“What do you think is so funny?” Iantha said. “You can’t possibly know what we’re talking about.”

I bit my lip in confusion; I knew there had been a joke, but its meaning hovered just outside my understanding. Why wouldn’t suitors want to hear a girl talk? What was funny or ridiculous about that? If a man liked a girl and wanted her for a bride, wouldn’t he want to know her thoughts? Especially if that girl was Iantha, whose stories and flights of fancy could have captivated the dullest rock. My favorite nights were those when Iantha agreed to tell us stories into the dark, inventing monsters and wondrous landscapes for our horror and delight. Coronis loved her stories too, though she was grudging about saying so. What were the other things the men would want, if not that? They made no sense, suitors. I couldn’t fathom why my sisters held them in such high regard.

“I know enough.”

“You don’t,” Coronis said. “And you shouldn’t have to know yet. It’s better that way.”

“Don’t rush into knowing,” Iantha murmured in agreement, as she put the finishing touches on my braid. “In any case, you’ll need to be a lot less wild and loud if you want suitors to take you seriously.”

“Maybe I don’t need them.” I held my chin high with a bravado I did not feel.

“You see?” Coronis stroked her smooth hair. “She does not know.”

It began the year after my first blood. My father had been calling on my sisters to sit in the presence of men who came to visit. Iantha and Coronis were to be silent and still as the men talked. I was also of marriageable age, but my father wanted to leave me out until he’d seen to the two elder girls. I was glad of this. I had no wish to join them, no wish to be betrothed; in fact, in that time, I spent my days studiously avoiding thoughts of the future, which seemed like a forest path that would grow narrower and more brambled with each step. Soon there would be nowhere to turn, no move that wouldn’t leave me stabbed by thorns, and no way of turning back. I was old enough now to understand that marriage was inevitable, no matter how little I wanted it. I did not envy my sisters. I searched their faces when they returned from that hall in the evenings. Sometimes I glimpsed streaks of pride or worry, and other times there were reactions I couldn’t decipher, hidden beneath a blankness I’d never seen in them before. I avoided the hall where my father received the strange men, devoting myself to helping the servants with the cooking, and to all the tasks of the women’s room: sewing, spinning, and above all the loom, whenever my mother let me have her seat. I wove ferociously. I wove as if the motion could slow time and keep me there forever, keep me free.

One afternoon, my mother sent me into the hall with a platter of sliced pears and goat cheese, for the enjoyment of the guests. Later, I would wonder whether she came to regret that decision and wish she’d gone herself, sent a kitchen girl, or at least made me veil my face. But who could say whether any of that would have made a difference? Perhaps, if that hadn’t been the day, the Fates would still have found a way to infiltrate my world with the venom-dipped thread of my destiny, for they say the threads of Fate will always find the human lives for which they were spun.

I felt the guest’s gaze on me as soon as I entered the room. Keen weasel eyes in a face sagging with sweat. He stopped speaking in the middle of a sentence and watched me put the platter on a table to his side. My father, sensing a shift in the air but unsure of its source, launched into fast talk, something about goats and ravines, but the man did not seem to be paying attention.

“Tell me, Lelex, who is this?”

“My third daughter, Psyche.” My father’s voice stayed courteous, but I heard the stiffness in it. The dismissal, meant for me.

I felt the eyes of the suitor rove my body. My father’s anger bright as flame. And my sisters’ confusion, beaming from them, the hardest part to bear.

My cheeks burned as I left the room. I stung with more than I could name. Humiliation. Invasion. Inner chaos. What had I done? How had I brought my family shame?

The next day, we were at work in the women’s room when a servant came to call the three daughters of the house into the main hall.

“What?” Iantha glanced at me. “Her too?”

“He said all three.”

The air bristled around us as we walked to the main hall. I felt the heat of my sisters’ thinking, but they did not say a word.

Three men sat with our father, one of them the suitor from the day before. My father gestured for us to sit along the wall, where three stools waited.

“There she is,” the first man said.

They stared at me openly, all of them at once. It was too many eyes. Even then, with only three men, I felt diminished by their looking and struggled to keep my hands still in my lap.

“So,” one finally crowed, “it was no lie.”

“You’ve lost your wager, Horace.”

“What wager?” said my father. “What’s this?”

The men laughed. They were merchants, they said, and the night before they’d gathered at a camp between this village and the next, talking over the fire. That was where the two new suitors had heard tell of a maiden more beautiful than the goddess Aphrodite herself, and not only more beautiful but also interesting in a manner Aphrodite could not claim, with her golden hair and pale skin, which everyone had long agreed to be the height of beauty and perhaps it was, perhaps it had been, perhaps it even always would be, but there was a different kind of beauty distilled to perfection in the mortal maiden in question, a different flavor, a different taste. Dark beauty, lush as night. They hadn’t believed the tales, but as the wine flowed they’d been drawn into the story, sparked by it, and ultimately moved to place their bets. Horace had bet against the existence of such a mortal girl, while the other man had bet in favor. Now they’d come to see with their own eyes.

The word taste dug into my skin like a splinter. I did not want to be tasted.

To either side of me I felt my sisters burn.

My father stroked his beard, a gesture he often used to hide bewilderment or inner turmoil, though those who didn’t know him might well mistake it for a sign of contemplative thought. I wanted to beg him to send the men away, to let me go, I did not want any part of their wager, not the win or loss.

But my father was trapped by the laws of hospitality, and could not easily send away his guests. A good and wealthy man receives visitors gracefully, for if not, what is he hiding? And whom might he anger? Guests are sacred to Zeus himself and could one day be a god in disguise. Stories abounded of such visits, steeped in warning. Like the story of Baucis and Philemon, who’d watched all their neighbors drown in a flood for spurning gods as guests. These particular men did not seem godly, but still, it was foolish to risk divine vengeance.

There was more to it, too, for my father. He seemed torn between warring parts of himself. The men’s intentions were murky, but their keenness appealed to his ambition. My father was a dreamer, susceptible to grand visions of what could be. Dreaming had driven his life, made him what he was. His great ambition was to secure his status as one of the most important landowners in our valley for he, Lelex, was also a Greek on new shores. He had set out alone from the land of his birth, having fought with his four older brothers for reasons he never spoke of but whose bitterness still lingered on his tongue. He’d sailed over the sea and traveled inland to find terrain where he could anchor a new life, in pursuit of dreams, manhood, prosperity. When he landed, he’d gone to the house of Iloneus, an older Greek who’d voyaged here some years before, and a farmer of some renown. There, while paying his respects, he’d found his bride, my mother, the prettiest of the girls despite her dark features, so he told it in later years to gatherings of men. She’d been young and well-formed, his bride; she should have given him sons. That she had failed to do so was the great curse of his life. In other ways, he’d prospered, raising fat and healthy sheep that supplied wool across the valley and beyond it, to coastal Poseidonia and the ships that launched out from its ports into the greater world. He had land and servants and well-stocked granaries. But his wife had failed him not once, not twice, but three times, saddling him with girls, and I, of course, like every daughter born in the wake of other daughters, was a surplus, a disappointment, a child who should not have been born.

I knew I was not supposed to exist long before I understood why.

Even so. Let my telling be complete. My father was not as cruel as he could have been, not as cruel as other fathers. When wine poured freely, he may have crowed about the curse of us, but sometimes he treated his misfortune as a joke. Ah, well, he’d say, raising his glass, no use complaining, for what can be done about the Fates?

Then he’d hold my mother’s gaze until she smiled.

And now, here he was, facing unexpected suitors. A man burdened with three daughters could not take such a thing lightly. Three daughters, three deadweights—but also, three opportunities to marry girls off to his advantage. Merchants like these were not the goal, but their admiration might be a useful tool.

I saw these calculations pass over his face as he studied the men and let them stare at me.

The visit wore on.

Sun bore in through the single window.

I fought not to fidget on the hard stool. I wanted to get back to the loom, where threads awaited my eager hands. But anytime I shifted in my seat, as if to rise and go, my father’s eyes flicked my way to remind me of my duty to spare him any hint of humiliation, strict, but also pleading, or at least I thought I saw a streak of pleading under the surface, and I could not bear to disappoint him. I kept my eyes down. This was expected of a modest girl, but also I couldn’t stand their gazes, these men from some night fire down the valley. I’d never walked all the way to the midpoint between this village and the next; they knew more of the world than I did, these men, knew how the valley breathed in the dark, how it felt to stoke a fire beneath the hum of stars, to ride up the peaks that ringed us and down the other side, to follow paths out of villages and into the wild zones between them. I wanted these things they had, wanted to ask them about such journeys, what it was like, how the wind felt as they moved through its veils, but they gave no sign of interest in my thoughts.

Instead, their stares invaded me.

How did my father not see the grime of their looking, the way it slunk right under my skin?

I had never experienced such a thing before and could not grasp what they meant by it; I had no way of shielding myself or turning their attention into anything else. That one of them could ever become my husband—my stomach turned as though I’d swallowed rotten meat. That I’d be forced to obey one of these men for the rest of my life. It could happen, of course, to me as to any girl, but sitting still for these men’s stares I felt I’d rather drown myself than succumb to such a fate.

Finally my father dismissed the three of us with a wave, and we returned to the women’s room. As soon as we were out of sight of the main hall, Coronis strode fast in front of us, her back a hard wall of reproach. Iantha kept her gaze fixed ahead of her and did not wipe the tears from her face.

In the women’s room, we set back to work. The air hung thick with heat, shared breath, unnamed thoughts. No one spoke. I took up the distaff and began to spin, while Iantha measured and coiled the strands. Coronis stood at the loom, where she wove and fumed, wove and fumed, eclipsed by her younger sister in the attentions of men, how could it be? She radiated disbelief, and I wanted to tell her that she could have those sweaty old men if she liked, she could take them all, but I didn’t dare say a word.

I spun.

It was good wool, for which our household had earned some modest fame. Spinning calmed me, though it paled in comparison to the loom. Weaving was expansive, a looping and connecting that echoed the patterns of a river after rain, and while weaving I felt large, a roaming soul. I often lost myself deliciously in waking dreams, tempted to veer into designs of my own imagining, to weave visions into being instead of staying faithful to the pattern at hand. Pictures sprang into my mind and my fingers ached to shape them, but these were temptations I had to resist. The loom was a place for serving the household, not for the fancies of some young girl, as my sisters had reminded me the few times I’d strayed. My mother had chided me more gently, Daughter, if you chafe at what is needed from you it will only cause you suffering, for life requires doing things whether or not we want to. I felt her eyes on me now, the warmth of their worry, but I would not meet her gaze. I spun and spun. The distaff heavy in my hand.

How much spinning lay ahead of me in this life and how much else?

I hoped the men would vanish. Prayed for it as I pulled the wool into thread to be measured, to be spooled, to be cut.

The next day, five men arrived: two from the day before, three new. They stayed long and late and drank too much of my father’s wine. I sat silent before them, on display, dissolving from my skin.

My father’s voice wove into theirs, talk and laughter, as he dutifully played the host—but he seemed unsettled. Shadows lengthened. Servants lit torches along the walls. The men had not risen to go. Finally, my father dismissed Iantha and Coronis with a wave of his hand, for it was clear that these men had no interest in their presence, and why waste an afternoon of women’s work? Yet I remained.

The men talked, fell to silence, talked again, did what they wanted, looked where they wanted, gave off their scent, the sweltering, sharp sweat of them. Their rancid hunger on my breath, moving into my body against my will. Inhale. Exhale. I had no defenses against it. I longed to make it stop but didn’t know how. My body was speared by them, no escape. Still. Ordered to be still. My mind rebelled and unlatched itself, roved elsewhere, to the curves of the river, yesterday’s leaves, the boil of kitchen pots. Anything to separate me from the room where I sat. I did not look at them, but they didn’t seem to care. They looked everywhere except my eyes, as if they assumed they’d find nothing there.

When they finally rose to go, my father gestured me away, and I walked down the hall in a body that felt changed, invaded, no longer my own.

The next day there were more, then more again. My father began to leave me with a servant to keep watch, for he could not waste his days overseeing crowds of suitors. For that was what they soon became: crowds. Each time men came, they took with them their stories of what they’d seen, a feat to boast about. They came from across the valley, and then, after a few weeks, from beyond it: men who’d traveled for days to lay eyes on the girl whose unusual beauty was said to rival that of the goddess Aphrodite herself.

Many rumors have flown about that time. Rumor moves faster than human legs, metamorphosing as she goes, all tongues and feathers and swift flight. In her restless hands, lies take the sheen of truth. So let me be clear, let me tell you as bluntly as I can: I never sought the attentions of those men. I did not want them to come see me, I did not revel in them, I longed for them to leave. I have been called arrogant, vain, greedy in my quest to beat Aphrodite on her own terrain. But none of it is true.

I was a beast in a cage, prowling.

Inside I paced and clawed and screeched.

Outside, I was forbidden to move or make a sound.

Eyes everywhere.

Sit, Psyche, sit still and be good.

Sit still and let them look at you.

Trapped by too many eyes.

They came in long trains and gawked through the windows uninvited.

They whispered in each other’s ears and laughed.

They stared and stared and stared.

It became an infestation.

Droves of them, from far and wide.

Men everywhere, too much wine poured and food surrendered on trays.

My father couldn’t keep up and grew haggard with the strain. Every night, he threatened to beat me if I embarrassed him the following day, if he heard even a word from the men that suggested his daughter had sullied his name, for his name had to be preserved above all else. Yet he did not dare beat me, for the cost to my face would be too great. Instead his blows landed on the servants or my mother. Any bruise I saw on them was the fault of my face.

I began to hate my face, to wish it gone.

I could feel the men’s staring gradually scraping it away.

None of us knew what to do. Nothing like this had happened before, in the known history of our valley or beyond. There were no clear rules or traditions to guide the way. My sisters ceased speaking to me, as if I’d betrayed them. When I tried to talk to them, they turned away.

From day to day, my father swung between pride at his sudden fame and outrage at the invasion. He tried dismissing the men; they gathered outside the door in wait.

He positioned me at a window with wool to spin, a basket of it large enough to last the day. “Look at her from outside if you must!” he shouted through the window, ignoring the protests that pummeled his back as he strode from the room. I was relieved that I at least had something to occupy my hands.

Ignore them, I thought. Breathe. Keep your head down. Focus on something else.

Still, the men thickened like flies outside the house. Some left gifts in the grass; my father sent the servants out at the end of the day to collect them, and grudgingly sized them up. Fruit. Ceramics. The occasional textile. Not enough, he complained, to make up for the way their presence had depleted his stores. Still, he sent servants out with refreshments on some days, depending on his mood. He vacillated between ignoring the men and playing the host, between hostility and graciousness, the sense that he’d gained new status and the fear that he’d lost control. The crowd in front of our house seemed a spectacle beneath his dignity. He was an important man, and his property deserved respect.

That was how he thought of the sheep enclosure: as a way to move the eyesore to the back of the house.

One morning, with no explanation, a servant led me to the place where the sheep slept at night, surrounded by fencing on three sides, with the fourth side against the back wall of our home. The flock had left for the day, to graze in the surrounding hills. Droppings exuded their scent, mixed into the smell of grass. On a stool, in that place made for livestock, I sat in the sun and the shade and the longer shade. I sat as the men gathered around me inside the enclosure and beyond it, I sat all day, spinning raw wool from a basket at my feet. I missed the loom, the wide act of weaving, but at least I could hold something in my hands, the distaff a kind of weapon I could wield, if not to fight men off, at least to distract me from them and my surroundings.

Even this did not deter the men, who kept arriving, with gifts or without them, genteel or abrasive, laconic or spewing words. They spoke to each other as if I were not there, except for when, at one point, they spent a few days telling me to smile, in an amusement that became among them a kind of sport, a game to while away the time. Who will get the smile out of that girl?

“Ho, look, I’ll do it, she won’t be able to resist me.”

“So you say, you fool.”

“Fool! Watch this—Psyche! Smile!”

“What’s the matter with her?”

“I didn’t come all this way not to see her when she smiles.”

“Me neither.”

“You did it wrong, that’s why it didn’t work.”

“Oh?”

“Nonsense—”

“Watch this. Dear girl, won’t you give us a smile?”

“She’s like a stone.”

“A perfectly carved stone.”

“Or hard metal.”

“Hephaestus himself couldn’t have forged her better.”

“Ha! Tell that to Aphrodite!”

“You, girl! I’m going to tell your father if you don’t smile.”

“Don’t listen to them, Psyche—they’re monsters.”

“Ah! You did it!”

“What?”

“She smiled.”

“I missed it—”

“Too bad for you.”

I hated this game.

I smiled only in fear.

My mother came out sometimes to watch me for a few brief moments, her face inscrutable but kind. I didn’t know why she wasn’t closing her heart to me the way my sisters had, how she could keep looking at me with love and concern even when her eyes were almost swollen shut from the last beating. I wished I could run away and take her with me—that together, the two of us could begin a new life where we could breathe. But there was nowhere to go. Only marriage lay ahead, and look what that had brought my mother. What would it mean to belong to one of those men who congregated outside? Their eyes had already told me more than I wanted to know about their souls. Young men, old men, rugged break-a-tree-trunk men, hunched men, defeated men, wealthy men, ragged men, haughty men, quiet men, anchored men, men afloat, men rippling with bitterness, men rippling with dreams, men alight with pain or rage or scorn, men desperate to prove themselves to other men, men brimming over with hopes they for some unfathomable reason seemed determined to pin on a young girl. My father let them all in, and though he grumbled that he had no choice because he couldn’t stop the flood, he also seemed greedy for them, as if suitors were like coins: the more you had, the richer you’d be.

But suitors are nothing like coins. Not at all.

You can gather them endlessly and still find yourself with nothing.

A year passed. The crowds persisted. Men who claimed to be suitors packed the sheep enclosure. They came from across the mountains; they came from across the seas. My father, in a fit of optimism about my prospects, and drunk perhaps with newfound fame, built a new, larger corral for me to sit in, which at least was free of sheep droppings.

Rumor had it that the suitors had claimed a copse of trees down by the river, at the edge of my father’s land, where, after staring at me, they went to rub themselves and spill their seed while I still shone fresh in their minds. Sometimes alone, sometimes together—so it was told by the old cook to one of the kitchen maids when they thought I couldn’t hear.

“They mutter things to each other.”

“What things?”

“About the girl Psyche, about this or that part of her, or whatever it is men mutter to each other in such copses of trees—you know.”

“I most certainly do not know!” A giggle from the kitchen maid, of horror or glee. “How can you suggest I’d know anything of the sort?”

“Hmmf!”

I didn’t know quite what they meant, but their laughter sank into my skin, haunted my nights.

My father heard this rumor, too. He was outraged. His daughter had been sullied and his own reputation bore the stain. For six days he refused to speak to me or look me in the eye, and I felt enfolded by the fog of my nebulous crime.

I learned from my sisters—their resentful whispers in the night, when they thought I was asleep—that news of these suitor visits had spread across the land. It had become so dramatic that it seemed Aphrodite herself was angry, for man after man had compared me favorably to the goddess, and even worse, the altar in her honor at the edge of our valley had grown neglected in my days of fame. Aphrodite was our patron goddess, this altar a main site of worship and requests for love, health, good crops, and other blessings. I had never seen it; I’d never traveled that far. But I’d heard about its beautiful stone table long as a house, carved into a cliff face, to which the devoted journeyed to offer gifts that now had stopped appearing. Her altar was bare. Spiderwebs bloomed in empty baskets. Flowers withered. Fruit rotted and yielded its flesh to crows and there was nobody to replace it. Panic flooded me at the news. It was terrible, dangerous, to anger the gods. I had done nothing, of course, but still, it was my name on wagging tongues. Would she, Aphrodite, all-seeing divine being, understand that I’d had no hand in spreading the stories of me, that I wanted no part of them? Or would I be punished for the acts of men?

“She won’t like it,” Coronis hissed. “The way Psyche is stealing from her.”

“I’m not stealing,” I whispered.

“Liar,” said Coronis.

“Go to sleep,” said Iantha.

But it was true, I was no thief. I tried to comfort myself: Aphrodite would see further than my sisters and give me reprieve. Surely she had more important things to do than worry about some peasant girl in a valley at the edge of the world. Why would she care? She was a goddess. She had altars everywhere, and grand temples in Greece, if my father’s tales of his homeland were to be believed. Aphrodite had all the power. She could do anything, be anywhere, exist forever on the great Mount Olympus where the gods lived, where eternity yielded its sweet nectar, or so it was said.

I thought the gods had all the power, while I had none, for I spent all day doing what I was told. I did not yet understand all the curves and eddies of power, that you don’t have to steal from the powerful to incur their wrath. You don’t, in fact, have to do anything at all. You only need to be perceived as the cause of their discomfort. If the powerful feel something they do not want to feel, and they decide you are to blame, your fate is sealed.

And the gods, they feel things. That too I would one day learn. Some mortals believe the gods don’t feel, that they transcend that inner realm somehow, but this I would come to see as one of the gravest mistakes a mortal can make.

I arrived at her palace by soaring from a rock where I’d been left for dead. How I came to be on that rock is not the core of my story, but it’s where I’ll begin—for all stories have roots, as plants do, as people do. As legends do. In the case of legends, too much distance from the root can twist the tale into a lie. Think of the hordes who want it that way, who obscure on purpose. You’ve seen it, haven’t you? The way they balk at a story with too many sharp edges or unfamiliar colors? How bards and gossips warp a tale to their will? I know why they do it, the allure of audience delight. The trouble comes when feeding that delight means flattening out what gives a story life and power, its wilder shapes, the jagged or the billowed, the spike and fall of songs usually buried under silence. There are truths that some don’t want to hear. Without those truths, stories lose their teeth. Limbs. Bones. It’s safer that way, for gossips and bards. Which is why I don’t trust them when it comes to my story with Eros, the story of Eros and me.

I wouldn’t trust them either if I were you.

Sit closer. Let me give you my telling, starting at the root.

According to my mother, I arrived in the last hour before sunrise, so fast the village healer didn’t come in time and instead I fell into the trembling hands of a kitchen maid. You burned, my mother said, like an arrow made of sunlight, as if you could shoot through me, as if you’d turned my flesh to air, that’s how you flew into the world. Insistent, you were. You wept that night as if you missed the motion. You were not quiet like your sisters when they were born. This frightened me, so I sang you an old song about the earth, to help you land here, my love, my dear Psyche. To blunt the longing. Girls need that.

“To be close to the earth?” I asked.

“To stop dreaming of flight.”

I was five then and entranced by the rare thrill of a walk alone with my mother as we carried the washing from the river. The story landed in me like a welcome stone, forming ripples I was still too young to understand.

Later I’d know.

About flight, and girls, and dreaming. How a body can be arrow, can be air, can burn.

When the men came, my world shattered—but before that, I was unafraid, and I knew joy. I will tell that, too, for I want you to have the whole story, a story as whole as I can weave in language not made to hold these truths, not made for me, or you. Perhaps you’ll know the feeling, and the limitations of my speaking won’t matter, you’ll understand. Perhaps you too recall a time when you were small and the days gleamed with secret light, as if the walls and bowls and stones and river and leaves each caught the sun inside them and shivered with the glow of their own being. I was completely alive inside. I was still free. Joy hid everywhere. In the scent of grass and dirt when I lay on the ground. In the feel of heat on my skin on summer days, and the whip of cold in winter. In the rush of the river around me when I bathed there, a living aqueous body surrounding mine. In the way a tree could subsume me, swallow my shadow into its own like water poured to water, blending dark with dark, a recognition and a coming home. In the ease of sinking my body into the cool scope of a tree, oak or olive, fig or pine, blended into them, until I felt my roots deep in the earth below and my head green with leaves reaching greedily up to the sun. In the rich murmur of rain against our roof, spilling tales from the heavens, a wet weeping and laughter of secrets I longed to translate or swim into with my human mind. I could stay up all night listening to the language of the rain. I dreamed I could be rain, sky, river, tree. I dreamed I could be melted by my love for the world. Poured and blended. Lost, remade.

These were silent journeys, utterly private. I never spoke of them to anyone. When I was very small, I thought everyone lived this way inside, in a constant connection to infinity. Including my sisters. Though in the end, it was my sisters who showed me how wrong I was to imagine that everyone was like me. Theirs was a different way of moving through the world. It was often my sisters who called me back from the dream-space, into the task at hand. Psyche, what are you doing, you’re distracted again, what’s the matter with you, hurry up, the dark is coming soon!

They were ever-present as the air itself, my sisters, Iantha and Coronis, Coronis and Iantha. Elegant and limber as the saplings that rise at the river’s shore. They towered over me; they interrupted my reveries but also brought shape and life to my days. These two tall girls who knew things I did not, who were older than me. I watched them in a kind of enchanted awe.

Iantha was the eldest, sharp-witted, always the first to know things: when a goat was about to give birth, which river rocks made the best stepping stones, how to stitch fast without stabbing your own fingers, when the traveling merchants had arrived in the village with ribbons and spices and thread. She had a laugh capable of reducing a person to the size of a mushroom, or warming the hardest stone. I feared that laugh and pined to hear it. Her presence woke me and yet dwarfed me, all at once. I wanted to be near her; I was nurtured by her shadow.

Coronis was the middle sister, the most fair. Her hair was the color of threshed wheat, though she preferred to hear it called the color of the sun. She could not match our elder sister in wits, but made up for it in charm, for she moved with a dancing grace even when picking figs or scrubbing pots, and when we were small it was she who had the reputation as a beauty bound to steal the hearts of men and earn her a place beside a king.

The two of them often kept their thoughts to themselves or to the tightly sealed container of their bond. With a quick glance they could enact a whole conversation that was impossible for me to decipher. They were inseparable even when they quarreled, even when they would not direct a word to each other. They’d learned to read each other’s thoughts before I was born; they saw no need to slow down their secret language so I could understand. I had the constant feeling that my older sisters held—in their palms, their thoughts, their voices—the keys to the world. I wanted to see or hear the glint of what they knew, what they shared with each other.

I’d follow them around as they played their games and did their spinning and weaving, or washed their clothes at the river. I often struggled to keep up with them on my shorter legs, and well they knew it, for they laughed at the sight of me loping out of breath to catch up with them in the forest, though at other times they’d help me through brambles or across the stream with its stepping stones. I was always determined to stay close and hear every word they exchanged, no matter the subject, as they whispered or chatted or howled: what they thought about this or that boy they’d glimpsed at a distance in the village; the meaning of a tale they’d heard the servants murmur at the fire; how to oil their hair so it shone as if lit from within.

When they oiled their hair, I watched them studiously, then snuck some of the unguent to try, hoping it might seep into my scalp and unlock some special powers in my mind, though all it got me was a scolding when I was discovered. Psyche! You’re too small for that! Look at the mess you’ve made! And only then did I see the slick puddle on the floor. I’d been so eager to reach for the bottle, entranced by olive oil, the way it made my fingers gleam and slide against each other, that I hadn’t noticed the spill. Messy Psyche. Wild, impulsive Psyche. As my sisters braided their hair—as well as mine, with calm, steady hands whose touch I relished—they talked their future husbands into being. My hair was the darkest among the three, a deep black punctuated by slender strands the shade of fertile soil. Secretly, I loved my hair, the only part of me that inspired a private—what? Not vanity, exactly, so much as a sumptuousness, a sensual joy in my own self, though of course I knew better than to breathe a word of it to anyone, how I liked to run my fingers through its richness when no one was looking, how the swing of braids against my body pleased me, how I loved that my hair took after our mother’s own black curls.

For I was dark like my mother, like the people of this valley before the Greek ships came. My mother’s mother was born three years before the Greeks arrived, with their spears and swords and insistence on claiming the land. They claimed the women, too, and the girls, especially the girls. I know little about my grandmother. I’ve pieced together her story from scraps of telling, dropped by my mother in the women’s room on long afternoons in a voice so quiet you had to lean in close to catch the words. I know my grandmother remembered her own mother weeping in the corner of the kitchen, curled into a ball behind a curtain of her loose black hair, because her husband had disappeared. The disappearance was never explained to my three-year-old grandmother beyond the words he is gone, which her mother repeated like a hymn or curse. There was no body, no blood, no funeral pyre, no tracks to where he might have fled, no speaking of his story or his name. Only an absence, soon filled by a Greek merchant who took my great-grandmother as his wife. She bore him more children. The children from before, like my grandmother, grew up careful to serve and obey and stay in their stepfather’s good graces, for their fate was now in his hands.

When my grandmother was fourteen, she was married off to a much older man who’d recently come from Greece. This was Iloneus, my grandfather. He established a farm across the mountains that ring our valley, happy to finally claim his own patch of earth, a far more fertile place than the rocky crags from which he’d sailed on his ship of hungry men, or so he told his children. My mother was among those children, listening quietly as she refilled his wine. She grew up speaking only Greek, for her father, Iloneus, forbade the old language from the home. It came to her only in music. Her mother hummed as she wove, sang softly in the night, soothed children with tunes when no one else could hear. Those are the songs my mother gave us when we were small, which enfolded my sisters and me, like the one she crooned when I was born. Old songs. In the old language, the language of the land, she sometimes called it. The melodies flowed like a stream over dark stones. Sounds unmade of meaning, unclasped from thought or time. Sounds that carried what could not be spoken, soul to throat to ear to soul. I didn’t learn the songs, but they settled in me, deep inside me and yet absent at the same time.

My mother was both Greek and something else, and the something else carried on in my olive skin and thick black hair. Not all the Greeks were pale and fair-haired, but our father was, and Coronis took after him, while Iantha was a blend of the two, her hair a medium brown, her skin tone somewhere between Coronis’s and mine. Both of my sisters took pride in their lighter locks and the rarity of their hazel eyes. They believed this would give them an advantage in the future, especially fair Coronis. It was not only vanity that made them think so, for everyone believed it, including my mother, who was the most beautiful woman I could ever have imagined yet who believed the daughters who were lighter than her stood the stronger chance with suitors. Nobody saw the future coming. Not one of us could have glimpsed it even in a dream.

“They will fall on their knees for us,” Iantha would say, tugging slightly too hard on a rope of my hair, braiding with efficient flicks.

Coronis smirked. “Especially for me.”

“Hmmf! Perhaps.” Iantha sounded grudging. “But I’ll make up for it with my wit; I’ll charm them with my stories. Sit still, Psyche.”

“Sorry.” I stopped my fidgeting so their talk would carry on.

“Ah, Iantha!” Coronis batted her playfully. “On what cloud are you? You think suitors want to hear a girl talk?”

They laughed, together. I laughed along, tentative, uncertain.

“What do you think is so funny?” Iantha said. “You can’t possibly know what we’re talking about.”

I bit my lip in confusion; I knew there had been a joke, but its meaning hovered just outside my understanding. Why wouldn’t suitors want to hear a girl talk? What was funny or ridiculous about that? If a man liked a girl and wanted her for a bride, wouldn’t he want to know her thoughts? Especially if that girl was Iantha, whose stories and flights of fancy could have captivated the dullest rock. My favorite nights were those when Iantha agreed to tell us stories into the dark, inventing monsters and wondrous landscapes for our horror and delight. Coronis loved her stories too, though she was grudging about saying so. What were the other things the men would want, if not that? They made no sense, suitors. I couldn’t fathom why my sisters held them in such high regard.

“I know enough.”

“You don’t,” Coronis said. “And you shouldn’t have to know yet. It’s better that way.”

“Don’t rush into knowing,” Iantha murmured in agreement, as she put the finishing touches on my braid. “In any case, you’ll need to be a lot less wild and loud if you want suitors to take you seriously.”

“Maybe I don’t need them.” I held my chin high with a bravado I did not feel.

“You see?” Coronis stroked her smooth hair. “She does not know.”

It began the year after my first blood. My father had been calling on my sisters to sit in the presence of men who came to visit. Iantha and Coronis were to be silent and still as the men talked. I was also of marriageable age, but my father wanted to leave me out until he’d seen to the two elder girls. I was glad of this. I had no wish to join them, no wish to be betrothed; in fact, in that time, I spent my days studiously avoiding thoughts of the future, which seemed like a forest path that would grow narrower and more brambled with each step. Soon there would be nowhere to turn, no move that wouldn’t leave me stabbed by thorns, and no way of turning back. I was old enough now to understand that marriage was inevitable, no matter how little I wanted it. I did not envy my sisters. I searched their faces when they returned from that hall in the evenings. Sometimes I glimpsed streaks of pride or worry, and other times there were reactions I couldn’t decipher, hidden beneath a blankness I’d never seen in them before. I avoided the hall where my father received the strange men, devoting myself to helping the servants with the cooking, and to all the tasks of the women’s room: sewing, spinning, and above all the loom, whenever my mother let me have her seat. I wove ferociously. I wove as if the motion could slow time and keep me there forever, keep me free.

One afternoon, my mother sent me into the hall with a platter of sliced pears and goat cheese, for the enjoyment of the guests. Later, I would wonder whether she came to regret that decision and wish she’d gone herself, sent a kitchen girl, or at least made me veil my face. But who could say whether any of that would have made a difference? Perhaps, if that hadn’t been the day, the Fates would still have found a way to infiltrate my world with the venom-dipped thread of my destiny, for they say the threads of Fate will always find the human lives for which they were spun.

I felt the guest’s gaze on me as soon as I entered the room. Keen weasel eyes in a face sagging with sweat. He stopped speaking in the middle of a sentence and watched me put the platter on a table to his side. My father, sensing a shift in the air but unsure of its source, launched into fast talk, something about goats and ravines, but the man did not seem to be paying attention.

“Tell me, Lelex, who is this?”

“My third daughter, Psyche.” My father’s voice stayed courteous, but I heard the stiffness in it. The dismissal, meant for me.

I felt the eyes of the suitor rove my body. My father’s anger bright as flame. And my sisters’ confusion, beaming from them, the hardest part to bear.

My cheeks burned as I left the room. I stung with more than I could name. Humiliation. Invasion. Inner chaos. What had I done? How had I brought my family shame?

The next day, we were at work in the women’s room when a servant came to call the three daughters of the house into the main hall.

“What?” Iantha glanced at me. “Her too?”

“He said all three.”

The air bristled around us as we walked to the main hall. I felt the heat of my sisters’ thinking, but they did not say a word.

Three men sat with our father, one of them the suitor from the day before. My father gestured for us to sit along the wall, where three stools waited.

“There she is,” the first man said.

They stared at me openly, all of them at once. It was too many eyes. Even then, with only three men, I felt diminished by their looking and struggled to keep my hands still in my lap.

“So,” one finally crowed, “it was no lie.”

“You’ve lost your wager, Horace.”

“What wager?” said my father. “What’s this?”

The men laughed. They were merchants, they said, and the night before they’d gathered at a camp between this village and the next, talking over the fire. That was where the two new suitors had heard tell of a maiden more beautiful than the goddess Aphrodite herself, and not only more beautiful but also interesting in a manner Aphrodite could not claim, with her golden hair and pale skin, which everyone had long agreed to be the height of beauty and perhaps it was, perhaps it had been, perhaps it even always would be, but there was a different kind of beauty distilled to perfection in the mortal maiden in question, a different flavor, a different taste. Dark beauty, lush as night. They hadn’t believed the tales, but as the wine flowed they’d been drawn into the story, sparked by it, and ultimately moved to place their bets. Horace had bet against the existence of such a mortal girl, while the other man had bet in favor. Now they’d come to see with their own eyes.

The word taste dug into my skin like a splinter. I did not want to be tasted.

To either side of me I felt my sisters burn.

My father stroked his beard, a gesture he often used to hide bewilderment or inner turmoil, though those who didn’t know him might well mistake it for a sign of contemplative thought. I wanted to beg him to send the men away, to let me go, I did not want any part of their wager, not the win or loss.

But my father was trapped by the laws of hospitality, and could not easily send away his guests. A good and wealthy man receives visitors gracefully, for if not, what is he hiding? And whom might he anger? Guests are sacred to Zeus himself and could one day be a god in disguise. Stories abounded of such visits, steeped in warning. Like the story of Baucis and Philemon, who’d watched all their neighbors drown in a flood for spurning gods as guests. These particular men did not seem godly, but still, it was foolish to risk divine vengeance.

There was more to it, too, for my father. He seemed torn between warring parts of himself. The men’s intentions were murky, but their keenness appealed to his ambition. My father was a dreamer, susceptible to grand visions of what could be. Dreaming had driven his life, made him what he was. His great ambition was to secure his status as one of the most important landowners in our valley for he, Lelex, was also a Greek on new shores. He had set out alone from the land of his birth, having fought with his four older brothers for reasons he never spoke of but whose bitterness still lingered on his tongue. He’d sailed over the sea and traveled inland to find terrain where he could anchor a new life, in pursuit of dreams, manhood, prosperity. When he landed, he’d gone to the house of Iloneus, an older Greek who’d voyaged here some years before, and a farmer of some renown. There, while paying his respects, he’d found his bride, my mother, the prettiest of the girls despite her dark features, so he told it in later years to gatherings of men. She’d been young and well-formed, his bride; she should have given him sons. That she had failed to do so was the great curse of his life. In other ways, he’d prospered, raising fat and healthy sheep that supplied wool across the valley and beyond it, to coastal Poseidonia and the ships that launched out from its ports into the greater world. He had land and servants and well-stocked granaries. But his wife had failed him not once, not twice, but three times, saddling him with girls, and I, of course, like every daughter born in the wake of other daughters, was a surplus, a disappointment, a child who should not have been born.

I knew I was not supposed to exist long before I understood why.

Even so. Let my telling be complete. My father was not as cruel as he could have been, not as cruel as other fathers. When wine poured freely, he may have crowed about the curse of us, but sometimes he treated his misfortune as a joke. Ah, well, he’d say, raising his glass, no use complaining, for what can be done about the Fates?

Then he’d hold my mother’s gaze until she smiled.

And now, here he was, facing unexpected suitors. A man burdened with three daughters could not take such a thing lightly. Three daughters, three deadweights—but also, three opportunities to marry girls off to his advantage. Merchants like these were not the goal, but their admiration might be a useful tool.

I saw these calculations pass over his face as he studied the men and let them stare at me.

The visit wore on.

Sun bore in through the single window.

I fought not to fidget on the hard stool. I wanted to get back to the loom, where threads awaited my eager hands. But anytime I shifted in my seat, as if to rise and go, my father’s eyes flicked my way to remind me of my duty to spare him any hint of humiliation, strict, but also pleading, or at least I thought I saw a streak of pleading under the surface, and I could not bear to disappoint him. I kept my eyes down. This was expected of a modest girl, but also I couldn’t stand their gazes, these men from some night fire down the valley. I’d never walked all the way to the midpoint between this village and the next; they knew more of the world than I did, these men, knew how the valley breathed in the dark, how it felt to stoke a fire beneath the hum of stars, to ride up the peaks that ringed us and down the other side, to follow paths out of villages and into the wild zones between them. I wanted these things they had, wanted to ask them about such journeys, what it was like, how the wind felt as they moved through its veils, but they gave no sign of interest in my thoughts.

Instead, their stares invaded me.

How did my father not see the grime of their looking, the way it slunk right under my skin?

I had never experienced such a thing before and could not grasp what they meant by it; I had no way of shielding myself or turning their attention into anything else. That one of them could ever become my husband—my stomach turned as though I’d swallowed rotten meat. That I’d be forced to obey one of these men for the rest of my life. It could happen, of course, to me as to any girl, but sitting still for these men’s stares I felt I’d rather drown myself than succumb to such a fate.

Finally my father dismissed the three of us with a wave, and we returned to the women’s room. As soon as we were out of sight of the main hall, Coronis strode fast in front of us, her back a hard wall of reproach. Iantha kept her gaze fixed ahead of her and did not wipe the tears from her face.

In the women’s room, we set back to work. The air hung thick with heat, shared breath, unnamed thoughts. No one spoke. I took up the distaff and began to spin, while Iantha measured and coiled the strands. Coronis stood at the loom, where she wove and fumed, wove and fumed, eclipsed by her younger sister in the attentions of men, how could it be? She radiated disbelief, and I wanted to tell her that she could have those sweaty old men if she liked, she could take them all, but I didn’t dare say a word.

I spun.

It was good wool, for which our household had earned some modest fame. Spinning calmed me, though it paled in comparison to the loom. Weaving was expansive, a looping and connecting that echoed the patterns of a river after rain, and while weaving I felt large, a roaming soul. I often lost myself deliciously in waking dreams, tempted to veer into designs of my own imagining, to weave visions into being instead of staying faithful to the pattern at hand. Pictures sprang into my mind and my fingers ached to shape them, but these were temptations I had to resist. The loom was a place for serving the household, not for the fancies of some young girl, as my sisters had reminded me the few times I’d strayed. My mother had chided me more gently, Daughter, if you chafe at what is needed from you it will only cause you suffering, for life requires doing things whether or not we want to. I felt her eyes on me now, the warmth of their worry, but I would not meet her gaze. I spun and spun. The distaff heavy in my hand.

How much spinning lay ahead of me in this life and how much else?

I hoped the men would vanish. Prayed for it as I pulled the wool into thread to be measured, to be spooled, to be cut.

The next day, five men arrived: two from the day before, three new. They stayed long and late and drank too much of my father’s wine. I sat silent before them, on display, dissolving from my skin.

My father’s voice wove into theirs, talk and laughter, as he dutifully played the host—but he seemed unsettled. Shadows lengthened. Servants lit torches along the walls. The men had not risen to go. Finally, my father dismissed Iantha and Coronis with a wave of his hand, for it was clear that these men had no interest in their presence, and why waste an afternoon of women’s work? Yet I remained.

The men talked, fell to silence, talked again, did what they wanted, looked where they wanted, gave off their scent, the sweltering, sharp sweat of them. Their rancid hunger on my breath, moving into my body against my will. Inhale. Exhale. I had no defenses against it. I longed to make it stop but didn’t know how. My body was speared by them, no escape. Still. Ordered to be still. My mind rebelled and unlatched itself, roved elsewhere, to the curves of the river, yesterday’s leaves, the boil of kitchen pots. Anything to separate me from the room where I sat. I did not look at them, but they didn’t seem to care. They looked everywhere except my eyes, as if they assumed they’d find nothing there.

When they finally rose to go, my father gestured me away, and I walked down the hall in a body that felt changed, invaded, no longer my own.

The next day there were more, then more again. My father began to leave me with a servant to keep watch, for he could not waste his days overseeing crowds of suitors. For that was what they soon became: crowds. Each time men came, they took with them their stories of what they’d seen, a feat to boast about. They came from across the valley, and then, after a few weeks, from beyond it: men who’d traveled for days to lay eyes on the girl whose unusual beauty was said to rival that of the goddess Aphrodite herself.

Many rumors have flown about that time. Rumor moves faster than human legs, metamorphosing as she goes, all tongues and feathers and swift flight. In her restless hands, lies take the sheen of truth. So let me be clear, let me tell you as bluntly as I can: I never sought the attentions of those men. I did not want them to come see me, I did not revel in them, I longed for them to leave. I have been called arrogant, vain, greedy in my quest to beat Aphrodite on her own terrain. But none of it is true.

I was a beast in a cage, prowling.

Inside I paced and clawed and screeched.

Outside, I was forbidden to move or make a sound.

Eyes everywhere.

Sit, Psyche, sit still and be good.

Sit still and let them look at you.

Trapped by too many eyes.

They came in long trains and gawked through the windows uninvited.

They whispered in each other’s ears and laughed.

They stared and stared and stared.

It became an infestation.

Droves of them, from far and wide.

Men everywhere, too much wine poured and food surrendered on trays.

My father couldn’t keep up and grew haggard with the strain. Every night, he threatened to beat me if I embarrassed him the following day, if he heard even a word from the men that suggested his daughter had sullied his name, for his name had to be preserved above all else. Yet he did not dare beat me, for the cost to my face would be too great. Instead his blows landed on the servants or my mother. Any bruise I saw on them was the fault of my face.

I began to hate my face, to wish it gone.

I could feel the men’s staring gradually scraping it away.

None of us knew what to do. Nothing like this had happened before, in the known history of our valley or beyond. There were no clear rules or traditions to guide the way. My sisters ceased speaking to me, as if I’d betrayed them. When I tried to talk to them, they turned away.

From day to day, my father swung between pride at his sudden fame and outrage at the invasion. He tried dismissing the men; they gathered outside the door in wait.

He positioned me at a window with wool to spin, a basket of it large enough to last the day. “Look at her from outside if you must!” he shouted through the window, ignoring the protests that pummeled his back as he strode from the room. I was relieved that I at least had something to occupy my hands.

Ignore them, I thought. Breathe. Keep your head down. Focus on something else.

Still, the men thickened like flies outside the house. Some left gifts in the grass; my father sent the servants out at the end of the day to collect them, and grudgingly sized them up. Fruit. Ceramics. The occasional textile. Not enough, he complained, to make up for the way their presence had depleted his stores. Still, he sent servants out with refreshments on some days, depending on his mood. He vacillated between ignoring the men and playing the host, between hostility and graciousness, the sense that he’d gained new status and the fear that he’d lost control. The crowd in front of our house seemed a spectacle beneath his dignity. He was an important man, and his property deserved respect.

That was how he thought of the sheep enclosure: as a way to move the eyesore to the back of the house.

One morning, with no explanation, a servant led me to the place where the sheep slept at night, surrounded by fencing on three sides, with the fourth side against the back wall of our home. The flock had left for the day, to graze in the surrounding hills. Droppings exuded their scent, mixed into the smell of grass. On a stool, in that place made for livestock, I sat in the sun and the shade and the longer shade. I sat as the men gathered around me inside the enclosure and beyond it, I sat all day, spinning raw wool from a basket at my feet. I missed the loom, the wide act of weaving, but at least I could hold something in my hands, the distaff a kind of weapon I could wield, if not to fight men off, at least to distract me from them and my surroundings.

Even this did not deter the men, who kept arriving, with gifts or without them, genteel or abrasive, laconic or spewing words. They spoke to each other as if I were not there, except for when, at one point, they spent a few days telling me to smile, in an amusement that became among them a kind of sport, a game to while away the time. Who will get the smile out of that girl?

“Ho, look, I’ll do it, she won’t be able to resist me.”

“So you say, you fool.”

“Fool! Watch this—Psyche! Smile!”

“What’s the matter with her?”

“I didn’t come all this way not to see her when she smiles.”

“Me neither.”

“You did it wrong, that’s why it didn’t work.”

“Oh?”

“Nonsense—”

“Watch this. Dear girl, won’t you give us a smile?”

“She’s like a stone.”

“A perfectly carved stone.”

“Or hard metal.”

“Hephaestus himself couldn’t have forged her better.”

“Ha! Tell that to Aphrodite!”

“You, girl! I’m going to tell your father if you don’t smile.”

“Don’t listen to them, Psyche—they’re monsters.”

“Ah! You did it!”

“What?”

“She smiled.”

“I missed it—”

“Too bad for you.”

I hated this game.

I smiled only in fear.

My mother came out sometimes to watch me for a few brief moments, her face inscrutable but kind. I didn’t know why she wasn’t closing her heart to me the way my sisters had, how she could keep looking at me with love and concern even when her eyes were almost swollen shut from the last beating. I wished I could run away and take her with me—that together, the two of us could begin a new life where we could breathe. But there was nowhere to go. Only marriage lay ahead, and look what that had brought my mother. What would it mean to belong to one of those men who congregated outside? Their eyes had already told me more than I wanted to know about their souls. Young men, old men, rugged break-a-tree-trunk men, hunched men, defeated men, wealthy men, ragged men, haughty men, quiet men, anchored men, men afloat, men rippling with bitterness, men rippling with dreams, men alight with pain or rage or scorn, men desperate to prove themselves to other men, men brimming over with hopes they for some unfathomable reason seemed determined to pin on a young girl. My father let them all in, and though he grumbled that he had no choice because he couldn’t stop the flood, he also seemed greedy for them, as if suitors were like coins: the more you had, the richer you’d be.

But suitors are nothing like coins. Not at all.

You can gather them endlessly and still find yourself with nothing.

A year passed. The crowds persisted. Men who claimed to be suitors packed the sheep enclosure. They came from across the mountains; they came from across the seas. My father, in a fit of optimism about my prospects, and drunk perhaps with newfound fame, built a new, larger corral for me to sit in, which at least was free of sheep droppings.

Rumor had it that the suitors had claimed a copse of trees down by the river, at the edge of my father’s land, where, after staring at me, they went to rub themselves and spill their seed while I still shone fresh in their minds. Sometimes alone, sometimes together—so it was told by the old cook to one of the kitchen maids when they thought I couldn’t hear.

“They mutter things to each other.”

“What things?”

“About the girl Psyche, about this or that part of her, or whatever it is men mutter to each other in such copses of trees—you know.”

“I most certainly do not know!” A giggle from the kitchen maid, of horror or glee. “How can you suggest I’d know anything of the sort?”

“Hmmf!”

I didn’t know quite what they meant, but their laughter sank into my skin, haunted my nights.

My father heard this rumor, too. He was outraged. His daughter had been sullied and his own reputation bore the stain. For six days he refused to speak to me or look me in the eye, and I felt enfolded by the fog of my nebulous crime.

I learned from my sisters—their resentful whispers in the night, when they thought I was asleep—that news of these suitor visits had spread across the land. It had become so dramatic that it seemed Aphrodite herself was angry, for man after man had compared me favorably to the goddess, and even worse, the altar in her honor at the edge of our valley had grown neglected in my days of fame. Aphrodite was our patron goddess, this altar a main site of worship and requests for love, health, good crops, and other blessings. I had never seen it; I’d never traveled that far. But I’d heard about its beautiful stone table long as a house, carved into a cliff face, to which the devoted journeyed to offer gifts that now had stopped appearing. Her altar was bare. Spiderwebs bloomed in empty baskets. Flowers withered. Fruit rotted and yielded its flesh to crows and there was nobody to replace it. Panic flooded me at the news. It was terrible, dangerous, to anger the gods. I had done nothing, of course, but still, it was my name on wagging tongues. Would she, Aphrodite, all-seeing divine being, understand that I’d had no hand in spreading the stories of me, that I wanted no part of them? Or would I be punished for the acts of men?

“She won’t like it,” Coronis hissed. “The way Psyche is stealing from her.”

“I’m not stealing,” I whispered.

“Liar,” said Coronis.

“Go to sleep,” said Iantha.