Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

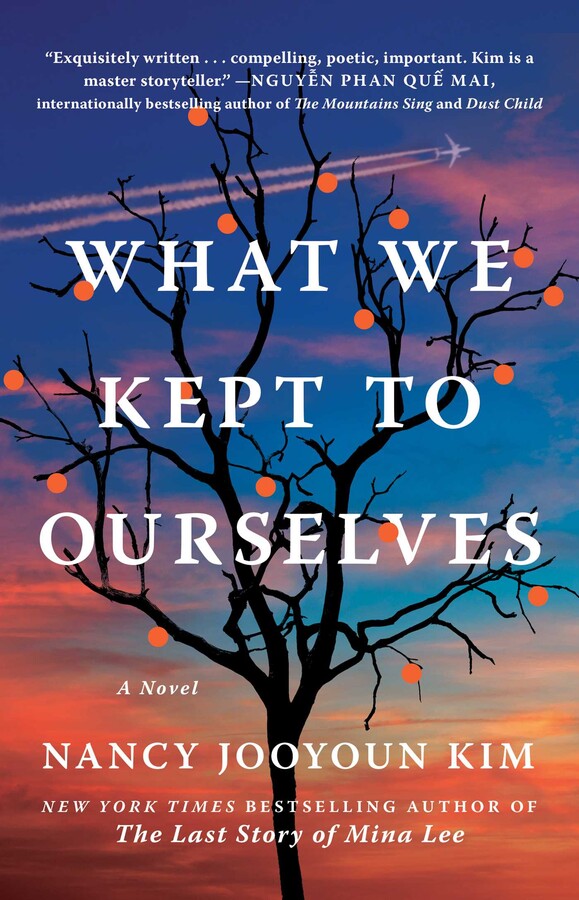

About The Book

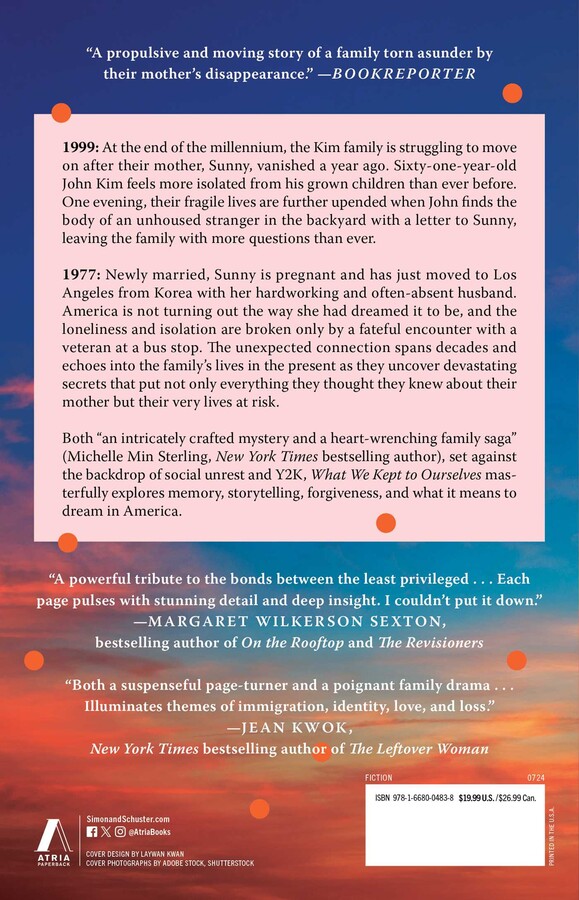

1999: At the end of the millennium, the Kim family is struggling to move on after their mother, Sunny, vanished a year ago. Sixty-one-year-old John Kim feels more isolated from his grown children than ever before. One evening, their fragile lives are further upended when John finds the body of an unhoused stranger in the backyard with a letter to Sunny, leaving the family with more questions than ever.

1977: Newly married, Sunny is pregnant and has just moved to Los Angeles from Korea with her hardworking and often-absent husband. America is not turning out the way she had dreamed it to be, and the loneliness and isolation are broken only by a fateful encounter with a veteran at a bus stop. The unexpected connection spans decades and echoes into the family’s lives in the present as they uncover devastating secrets that put not only everything they thought they knew about their mother but their very lives at risk.

Both “an intricately crafted mystery and a heart-wrenching family saga” (Michelle Min Sterling, New York Times bestselling author), set against the backdrop of social unrest and Y2K, What We Kept to Ourselves masterfully explores memory, storytelling, forgiveness, and what it means to dream in America.

Excerpt

With his girlfriend’s T-shirt draped over his face, Ronald bathed in her favorite scent, Juniper Breeze. The perfection of that evergreen was unlike the seasonal high-school fragrance variations on American desserts—peppermint sticks and gingerbread and sugar cookies.

His parents never baked; ovens were for storing pots and pans. Many of the immigrant kids, or the children of immigrants like himself, who came from predominantly Latino and Asian families, didn’t have homes filled with pies or cupcakes. Yet everyone at school wanted to smell the same way, longed for the comfort of some common nostalgia, whether it belonged to them and their histories or not. But comfort to him smelled of his mother in the kitchen, her hands in plastic gloves, massaging red pepper flakes, salt, a dash of white sugar, garlic, and saeujeot into the chopped leaves of a napa cabbage. He would stand beside her at the counter, and every time she taste-tested the kimchi, she’d place a child’s bite-sized portion in his mouth, careful not to deposit the scarlet paste on his face, her plastic gloves crinkled on his lips. She’d ask, “What do you think?”

But nobody in America celebrated the smell of kimchi. The only non-Korean he knew who actually loved kimchi was his girlfriend Peggy, who was Filipina and stopped at the Korean market every time she was in town, where she’d load up on her favorite banchan—kkakdugi, seasoned spinach, and jangjorim.

A week ago last Friday, Ronald had strummed his fingers against the warmth of Peggy’s stomach, along the bottom edge of her pale pink bra with the tiniest bow between her breasts, as his mouth touched the cup of her perfect navel. At first she flinched at the coldness of his fingers, then smirked, her eyes closed in pleasure. He kissed her lips, which were smooth and small and ripe, the color of berries.

They had met back in middle school in Hancock Park, where her family had lived about two to three miles away from him yet worlds apart, with its distinctive multimillion-dollar residences, formal hedges, country club, and healthy white people. But her family had fled four years ago to La Cañada for the obvious—the lack of crime and homelessness, the better schools, the serene isolation of the foothills by the Angeles National Forest, and the full amenities of neighboring Pasadena and Glendale. Her father was a doctor, and her mother, some kind of manager or administrator at the VA.

And he loved her. Peggy Lee Santos. They loved each other still. Even though he could not follow her to the fancy places she would go, the private universities that she researched with her seemingly infinite hours on AOL, he would drive to the end of the world for her in his father’s beat-up, ugly Eldorado.

Pots and pans clattered like sad cymbals less than ten feet from his door in the kitchen where his father prepared dinner. Frustrated, Ronald pulled Peggy’s T-shirt off his face and switched on his desk lamp, washing in glare the import-car posters—images of shiny modified Hondas flanked by models—around his bed. He didn’t even know why he had these posters anymore. For a little while, before he could actually drive, he had been interested in cars—the speed, the acceleration, the women—but now these images, curling at the corners, functioned only as distractions to cover the emptiness of the dirty white walls.

In a photo that his older sister Ana had framed for him on his desk, Ronald and his mother posed after his middle school graduation. Her face glowed as she clutched him with manicured fingers around his shoulders. She never had the time to do her nails, but she’d painted them that morning in front of her vanity. He remembered how much pride she exuded that day, but he could also sense—because he and his mother always had this way between them—her sadness over his growing up so fast.

How embarrassed he had felt that day beside her, as if he was too grown to be babied by his mother. But what he would give to hold her hand now. How much they could say to each other without words, how much they knew about each other in a squeeze of the shoulder, a quiet observation of one another through an open door, a mirror, a glance. His father, on the other hand, had always been unknowable, opaque, a dull stone worn smooth by time.

He didn’t believe his father’s claim that she was dead. There was no body. There was no proof.

Ronald had the itch to log on to see if he could find Peggy or any of his friends. Although they had already made plans to meet up in Pasadena tonight, he needed an escape now. But his father always got angry when he clogged up the phone line before nine p.m. Who knew who could call the house? They should all be available—just in case. But his father never acknowledged for whom or what they had been waiting.

Instead, their lives were a constant away message.

His father had set the breakfast nook for dinner—paper napkins, metal chopsticks, spoons. They hadn’t used the dining room table since his mother disappeared. Ronald slid onto the bench in front of the oxtail soup, the meat and bone and mu which had simmered for hours last night in a garlicky salt-and-pepper broth. Steam delicately painted the air with the rich and oily smell of gelatin and beef. Even if his father underseasoned and never bothered to brown anything, time and low heat performed most of the work.

“Did you sell all the Christmas stuff at the shop?” Ronald asked.

“What, the garlands?” John set his bowl of rice in front of Ronald, then winced as he bent to sit.

“The poinsettias. The ones you were making such a big deal about.”

“Yeah, yeah. Almost gone. More come in the morning,” his father said.

The soup was too hot, so instead Ronald sampled the baechu kimchi that his father bought. Without his mother, no one bothered to make kimchi at home. His mother would prepare jars and jars that they’d eat from almost every night, which his sister Ana found to be repetitive and dull. Sure, Ronald craved cheeseburgers and fast food too, but Ana claimed to dislike all the spice, and she hated the chopsticks, always using a fork instead. She had to make everything some kind of protest. No wonder why she liked Berkeley.

“Can I take the car out tonight?” Ronald asked.

“How long?”

“Couple hours.” He spooned the tender meat off the knobby bones, which he discarded onto his napkin.

“Your homework?” his father asked.

“It’s Friday.” Ronald hated his father’s voice—the graininess from all his years of smoking, the heaviness of the tone, the accent, which wasn’t quite Korean but distinctly foreign. His sister had once explained that since their father had immigrated in the early sixties, he’d picked up his accent from speaking English with Chinese Americans, Black customers, and Jewish shopkeepers who were then prevalent in the areas of South LA where he’d worked. But whatever the reason, his father’s accent always embarrassed Ronald. He was embarrassed for his father. His mother could hardly speak English, but he preferred her voice to his whenever she tried. She could play off anything through her tact and charm, her sense of humor. Her laugh, a ho, ho, ho, which she covered with her hand.

“And?” his father asked.

“Can I borrow the car?” Ronald said as clearly as possible.

His father sucked the meat from between his teeth. “Bring the car back before midnight.” His purplish lips frowned. “No drink. No smoke. No pregnant, uh, okay?”

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Introduction

The New York Times bestselling author of the Reese’s Book Club pick The Last Story of Mina Lee returns with a timely and surprising new novel about a family’s search for answers following the disappearance of their mother.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. What We Kept to Ourselves is told in alternating timelines, one set in 1977 and the other in 1999. Sunhee (later Sunny) and John change significantly between these two periods of their lives. What were your first impressions of them in 1977 in comparison to them in 1999? Did these impressions change throughout the novel?

2. John and Sunny are both Korean refugees, but they did not experience the war and its effects the same way. How were they different? How do you think their pasts dictate the people they become and ultimately the choices they make in the novel?

3. The Kim family is broken into two generations: the parents, Sunny and John, and their children, Ana and Ronald. How do the two generations and their experiences in the United States contrast? Discuss how these differences impact their behavior and how they each respond to the tragedies and struggles throughout the novel.

4. Sunny and RJ develop a strong friendship throughout the novel. Discuss their relationship and its significance to each - of them. What were they each looking for when they befriended each other? Did this change throughout the years as their personal lives evolved?

5. Ronald and Ana are able to learn about RJ’s past as a helicopter mechanic in Vietnam before he became unhoused in Los Angeles. Discuss the factors that led to such a drastic change in circumstances? Do you believe the “system” or society failed him? Did it fail any other characters?

6. Art becomes an outlet of freedom for Sunny, returning her to a part of her past that she had given up. Do any of the other characters have the sense of freedom that she craves?

7. Sunny’s relationship with Professor Cho evolves throughout the novel. What does Professor Cho symbolize to Sunny at the different points in their relationship?

8. Sunny’s experiences in the US have a cumulative impact on her worldview and happiness. Discuss the most significant of those experiences. What pushed her to a breaking point and led to her departure?

9. Sunny and John both develop friendships outside of their marriage, Sunny with RJ and John with Priscilla. Compare and contrast these friendships and what they meant to Sunny and John.

10. Throughout the novel, what city a character lives in has a significant impact on their experience. Discuss how both Los Angeles and Seoul affect each character and how each character’s experience of both cities evolves throughout the story.

11. Each character brings something different to the novel. Which character did you connect with the most and why?

12. The novel culminates in two surprising events. How did the conclusion make you feel? Were you satisfied with each family member’s narrative arc and the lessons they each understood throughout the novel?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. RJ is an integral part of Sunny’s story. As an unhoused veteran, he represents a growing population in the United States. A recent Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) study found that nearly 600,000 people are unhoused on any night. Look into programs in your area to help the unhoused. Donate or volunteer at your local shelter with your book club members.

2. Food is a key part of the family and community throughout the novel. Try this recipe from the author with your group.

SHROOMY VEGGIE-HEAVY JAPCHAE

Japchae is a savory and versatile noodle dish perfect for gatherings and parties. Although japchae is best after being warmed up in a pan, it can also be served at room temperature, which makes it easily transportable and great for potlucks. My version below is meatless but can be tweaked by substituting the dried shitake mushrooms with a bit of bulgogi that can be purchased at a Korean supermarket or made separately.

Ingredients

6 oz. (or a handful) of dried dang myeon (sweet potato noodles)

sesame oil

soy sauce

granulated sugar

pan-frying oil (grapeseed, vegetable, olive, etc.)

toasted sesame seeds

½ white or yellow onion, thinly sliced

1 medium carrot, cut into matchsticks

4–5 large, dried shitake mushrooms, soaked in warm water for about half an hour, stemmed and thinly sliced (or substitute in bulgogi if you prefer to include beef)

½ pound crimini or brown mushrooms, stemmed and thinly sliced

1 inch of ginger root, grated

1 bunch of spinach, washed well and thinly sliced

1 yellow or red bell pepper, seeds removed and cut into matchsticks

1 tablespoon of grated or finely chopped garlic

2 scallions, thinly and diagonally sliced

Boil a large pot of water for the noodles, following the package directions, until they are cooked through, about five or so minutes. Drain and rinse the noodles until cold. Shake them so they’re dry as possible, and then set them aside in a large bowl.

Mix the noodles in the large bowl with about 1 tablespoon of sesame oil, 2 teaspoons of soy sauce, and a teaspoon of sugar. Make sure the noodles are evenly coated. (Some people like their noodles oilier, sweeter, or saltier than others, but start with these proportions and adjust to taste later.)

Cook onion over medium heat in a skillet with pan-frying oil until soft, stirring occasionally. Season with a little salt. Then add to the large bowl of noodles.

Cook carrots and shitake mushrooms, separately, using the same instructions as the onion above. Add pan-frying oil as needed to get everything nice and soft.

Cook the fresh mushrooms with ginger, and stir until the mushrooms have released their liquid and the pan is mostly dry. Then add the cooked mushrooms to the large bowl of noodles.

Add more oil if needed and cook the spinach until it wilts, for about two minutes, and then drain any liquid from the pan. Continue to drain the greens in a colander above a sink or dish.

Cook the bell pepper like the carrots above, until soft.

Squeeze excess water from the spinach, which has been cooling down and draining in a colander.

Toss everything together in the large bowl along with the grated garlic, 1 tablespoon of soy sauce, 1/2 tablespoon of sugar, some cracks of ground pepper, 1 tablespoon of sesame oil, and 1 tablespoon of roasted sesame seeds. Taste and adjust seasoning to your preference.

Top everything with the sliced scallions and a sprinkle of more seeds. Make it pretty, as my mom says, and serve.

3. To learn more about Nancy Jooyoun Kim, learn about events, and read her debut and Reese’s Book Club pick, The Last Story of Mina Lee, visit Nancy’s official site at www.nancyjooyounkim.com.

A Conversation with Nancy Jooyoun Kim

Q: Stories focused on family dynamics are evergreen in literature—why did you choose to explore the different relationships within the Kim family?

A: On the surface, the Kims appear to be an average immigrant and working-class family in Los Angeles. There are security bars over their windows, concrete instead of plants and dirt, neighbors who are too busy or suspicious to get to know each other. They are a very American family—yet in mainstream culture, we rarely see nuanced representations of people like them.

But as I’ve thought about this book off and on for almost twenty years (!!), the Kim family, upon closer inspection, is also a microcosm of a divided America, seemingly at war with itself, sometimes so much that it reminds me of the Korea from which the Kims fled, first internally as refugees in the 1950s, and then externally in the ’60s and ’70s as immigrants to the United States.

There’s a father who can’t move on and refuses to admit that he had given his life to a dream that might just be that only, or even the opposite—someone else’s nightmare. A progressive daughter who can’t figure out a way to live her values and not die from boredom or a lack of pay. A mother who is a woman who has gone missing long before she actually disappears. The silences, the secrets, and the shames of this family aren’t too different from the ones we might experience more broadly in a country that hasn’t seemed to quite yet figure out how to live and move forward with the weight of its past.

Q: What was your inspiration for writing the novel?

A: I started writing a version of this novel almost twenty years ago, and my first inspiration was the sudden death of my father, whom I had been estranged from and hadn’t spoken to in months. My parents divorced when I was young, and our relationship had always been difficult.

When he died in a car accident, I had suddenly become responsible for not only his body but the many artifacts, the evidence of who he was that he had unknowingly left behind. So the tragedies and the failures and the ways that he found to cope and endure despite them inspired the character of John, and the novel’s opening—a man in his sixties driving a large, dilapidated car that he doesn’t even quite need into a sunset before the apocalypse.

The plot of the novel was partially inspired by encounters I have had with the unhoused in California, which has the largest relative proportion of unhoused people in the country. This crisis is very much a part of everyday life here in the Bay Area, and I wonder often about the stories behind what are at times the most abject cases.

I don’t understand how we can continue to accept such extreme poverty in a country that is seen as the “land of opportunity” abroad. Thus, this novel explores what it means to own a home, for immigrants and working- and middle-class Americans, when the basics of community and shelter have been readily denied to so many through policies and practices that don’t protect people equally.

Q: What novels were you drawn to growing up? Have these changed as you evolved as an adult?

A: I was a “very serious young reader.” Growing up, I was mostly drawn to what I would consider to be “difficult books.” I adored the modernists, and I had a thing for writers of the American South, like Faulkner and Tennessee Williams.

College, interestingly, exposed me to genre and what people often deem to be “less academic” reading, which I completely disagree with now. I took a course in African American detective fiction that changed my life.

Now I’m open to reading the best of everything—nonfiction, science fiction, detective, romance, etc. Genre to me is an expression of authorial intent and theme, and certainly worthy of study for a variety of reasons.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from your novel?

A: That there are many ways to create and share your own story right now. That generations before us, even if we might not have had a common language, attempt to speak to us all the time—through food and culture and music. That if we ever question why people kept us in the dark or didn’t share enough, we must equally question ourselves and what we leave behind for others to help make sense of and create meaning in this life.

Q: Why did you choose to set the novel in the 1970s and 1999?

A: The year 1999 was a pivotal moment for the internet in what felt like a very close encounter with a potentially human-made and completely stupid-seeming apocalypse. The internet and the personal computer changed how people, in their homes communicated, silently, sometimes anonymously, across a vast span of distance, and occasionally reversed the roles of parents and children. Adults could now learn something very valuable from their kids. This shift reminds me a lot of a dynamic that has been eternally present within immigrant families—the child as translator, sometimes chaperone of parents through a foreign country.

I chose the 1970s primarily because my own mother immigrated to this country in that decade and that meant less research for me! But as I thought more about the decade and what it meant to us a country, I came upon this realization through a Nathaniel Rich article in the New York Time Magazine—that despite its great hair, glitz, and glamour, the ’70 was also the beginning of the decade when scientists fully understood the danger of climate change (1979–89) and, depressingly, it could’ve been stopped. This reminded me of the everyday role of gasoline in people’s lives during that time period, how my father, like John himself, owned a gas station in south LA, and why in the ’80s, gasoline had become cheap enough to “guzzle.” There’s so much combustion in my novel, right?

Q: If you had to pick a favorite landmark in Los Angeles, what would it be?

A: I have so many, including the Griffith Obsveratory, the location of such emotional scenes in this book, but if I have to choose one, it’ll always be the Santa Monica Pier, which I featured in my first book, The Last Story of Mina Lee. Both locals and tourists from all over the world visit the pier, and walking down it is an adventure and immersion in so many languages, cultures, and ways of life. It’s also a poignant reminder that no matter where you come from, most people simply want to be outside and to keep falling in love with being alive.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (July 2, 2024)

- Length: 416 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668004838

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“What We Kept to Ourselves is both a suspenseful page-turner and a poignant family drama. Kim's beautiful, thoughtful prose illuminates themes of immigration, identity, love, and loss. A gorgeous, thrilling read!”—Jean Kwok, New York Times bestselling author of Girl In Translation

“Bursting with yearning, twists, and secrets, What We Kept to Ourselves is about the difficult questions that die in our throats when it comes to asking our loved ones. A triumph!”—Frances Cha, author of If I Had Your Face

“A gorgeous literary novel featuring poetic prose and a propulsive mystery. What We Kept to Ourselves is a moving story about immigration, family secrets, and human connection. Truly a masterpiece that I couldn’t put down.”—Emiko Jean, author of Mika in Real Life

"A powerful tribute to the bonds between the least privileged, each page of What We Kept to Ourselves pulses with stunning detail and deep insight. I couldn't put it down."—Margaret Wilkerson Sexton, bestselling author of On the Rooftop

“Kim's second novel is hard to put down, unique, haunting, and beautifully written, as the author slowly weaves layer upon layer in an intricate, mysterious web.”—Booklist, starred review

“Layers after layers of mystery are revealed with each chapter of this exquisitely written novel. What We Kept to Ourselves is a compelling, poetic, important, thought-provoking, and unforgettable read. Nancy Jooyoun Kim is a master storyteller who has the power to keep us spellbound and reminds us what we must do to make this world a better place.”—Nguyen Phan Que Mai, internationally bestselling author of The Mountains Sing and Dust Child

"Nancy Jooyoun Kim has crafted a moving, propulsive story about a family haunted by secrets. What We Kept To Ourselves spans the intimately personal to the urgently political to investigate how the traumas of the past shape the human experience. This is a probing, sharp novel about family, loss, desire, grief, the search for justice, and so much more."—Crystal Hana Kim, author of If You Leave Me

“Nancy Jooyoun Kim’s What We Kept to Ourselves illuminates the glacial secrets among a family that crackle under a glass lens. Through the brushstrokes of tragedy and grief and mystery, Kim interrogates how a forgotten past bleeds into the choices we make in our everyday lives."—E. J. Koh, author of The Liberators

“What We Kept to Ourselves is a nail-biting thriller with hairpin turns, a generational saga, a love story, an unsparing look at belonging and unbelonging in America today and the abject joys of food, family, forgiveness. I can’t stop thinking about the Kim family. A glorious achievement!” —Marie Myung-Ok Lee, author of The Evening Hero

"A propulsive mystery about yearning, loneliness, and duty (but to and for whom?). Kim is a masterful wordsmith, tackling brittle topics with grace, urgency, and most importantly, hope. This book is a call to action, and a reminder that it's never too late to live the life you've always wanted."—Carolyn Huynh, author of The Fortunes of Jaded Women

"Those of us who love southern California know it's an entire universe where people's dreams and loves and families orbit and dance and collide in neighborhoods as diverse as the world. Nancy Jooyoun Kim knows Los Angeles so deeply that her novel brings to life loquat trees, the melancholy of staying where new roots sometimes cannot flourish, and the geography of neighbors and strangers whose loyalties turn into what might be love." —Susan Straight, National Book Award Finalist and author of In the Country of Women

"What We Kept to Ourselves is an intricately crafted mystery and a heart-wrenching family saga. Nancy Jooyoun Kim writes with a piercing moral clarity, suffusing every page with emotional depth. Fiery, bittersweet and complex, this is a novel of incredible conviction and empathy."—Michelle Min Sterling, New York Times bestselling author Camp Zero

"What We Keep to Ourselves is a breathtaking literary force of a novel. With melodious prose, Nancy Jooyoun Kim has crafted a page-turning mystery with thoughtful meditations on family, love, and connection. This novel is a searing portrait on how long-buried secrets, desperate hopes, and blind compromises shape the decisions that affect generations to come. Kim is a master storyteller!"—Catherine Adel West, author of Saving Ruby King

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): What We Kept to Ourselves Trade Paperback 9781668004838

- Author Photo (jpg): Nancy Jooyoun Kim Photograph by Andria Lo(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit