Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

From #1 New York Times bestselling author Jason Reynolds, a “funny and rewarding” (Publishers Weekly) coming-of-age novel about friendship and loyalty across neighborhood lines and the hardship of life for an urban teen.

A lot of the stuff that gives my neighborhood a bad name, I don’t really mess with. The guns and drugs and all that, not really my thing.

Nah, not his thing. Ali’s got enough going on, between school and boxing and helping out at home. His best friend Noodles, though. Now there’s a dude looking for trouble—and, somehow, it’s always Ali around to pick up the pieces. But, hey, a guy’s gotta look out for his boys, right? Besides, it’s all small potatoes; it’s not like anyone’s getting hurt.

And then there’s Needles. Needles is Noodles’s brother. He’s got a syndrome, and gets these tics and blurts out the wildest, craziest things. It’s cool, though: everyone on their street knows he doesn’t mean anything by it.

Yeah, it’s cool…until Ali and Noodles and Needles find themselves somewhere they never expected to be…somewhere they never should've been—where the people aren’t so friendly, and even less forgiving.

A lot of the stuff that gives my neighborhood a bad name, I don’t really mess with. The guns and drugs and all that, not really my thing.

Nah, not his thing. Ali’s got enough going on, between school and boxing and helping out at home. His best friend Noodles, though. Now there’s a dude looking for trouble—and, somehow, it’s always Ali around to pick up the pieces. But, hey, a guy’s gotta look out for his boys, right? Besides, it’s all small potatoes; it’s not like anyone’s getting hurt.

And then there’s Needles. Needles is Noodles’s brother. He’s got a syndrome, and gets these tics and blurts out the wildest, craziest things. It’s cool, though: everyone on their street knows he doesn’t mean anything by it.

Yeah, it’s cool…until Ali and Noodles and Needles find themselves somewhere they never expected to be…somewhere they never should've been—where the people aren’t so friendly, and even less forgiving.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1

“Okay, I got one. Would you rather live every day for the rest of your life with stinky breath, or lick the sidewalk for five minutes?” Noodles asked. He turned and looked at me with a huge grin on his face because he knew this was a tough one.

“It depends. Does gum or mints work?”

“Nope. Just shit breath, forever!” He busted out laughing.

I thought for a second. “Well, if I licked the ground, I mean, that might be the grossest thing I could ever do, but when the five minutes was up, I could just clean my mouth out.” In my head I was going back and forth between the two options. “But if I got bad breath, forever, then I might not ever be able to kiss the ladies. So, I guess I gotta go with licking the ground, man.”

Just saying it made me queasy.

“Freakin’ disgusting,” Needles said, frowning, looking out at the sidewalk. “But I would probably do the same thing.”

A sick black SUV came flying down the block. The stereo was blasting, but the music was all drowned out by the loud rattle of the bass, bumping, shaking the entire back of the truck.

“Aight, aight, I got another one,” Noodles said as the truck passed. He shook his soda can to see if anything was left in it. “Would you rather trade your little sister for a million bucks, or for a big brother, if that big brother was Jay-Z?”

“Easy. Neither,” I said, plain.

“Come on, man, you gotta pick one.”

“Nope. I wouldn’t trade her.”

Another car came cruising down the street. This time, a busted-up gray hooptie with music blasting just as loud as the fresh SUV’s.

“So you tellin’ me, you wouldn’t trade Jazz for a million bucks?”

“Nope.”

“You wouldn’t wanna be Jay-Z’s lil brother?” Noodles looked at me with a side eye like I was lying.

“Of course, but I wouldn’t trade Jazz for it!” I said, now looking at him crazy. “She’s my sister, man, and I don’t know how you and your brother roll, but for me, family is family, no matter what.”

Family is family. You can’t pick them, and you sure as hell can’t give them back. I’ve heard it a zillion times because it’s my mom’s favorite thing to say whenever she’s pissed off at me or my little sister, Jazz. It usually comes after she yells at us about something we were supposed to do but didn’t. And with my mom, yelling ain’t just yelling. She gives it everything she’s got, and I swear it feels like her words come down heavy and hard, beating on us just as bad as a leather strap. She’s never spanked us, but she always threatens to, and trust me, that’s just as bad. It happens the same every time. The shout, then the whole thing about family being family, and how you can’t pick them or give them back. Every now and then I wonder if she would give us back, if she could. Maybe trade Jazz and me in for a little dog, or an everlasting gift card for Macy’s, or something. I doubt she’d do it, but I think about that sometimes.

Me and Jazz always joke about how we didn’t get to choose either. Sometimes we say if we had a choice, we would’ve chose Oprah for a mom, but the truth is, we probably still would’ve gone with good ol’ Doris Brooks. I mean, she’s a pretty tough lady and she don’t always get it right, but there’s no doubt that she loves us. And we know we’re lucky, even when we’re getting barked at. Plus, it’s not always about us. I mean, sometimes it is, but other times it’s about other things, like our mom just being stressed out from work. She’s a social worker, and all that really means is that she takes care of mentally sick people. She makes sure they get things they need, kind of like being a step-step-stepmother to them. At least that’s the way she breaks it down to us. I could see how that could be stressful, so Jazz and I do the best we can to not add to it.

What’s crazy is that we don’t ever really see our mother that much anyway, mainly because she also has another gig at a department store in the city. So she works with the mentally ill from nine to five, and then sells clothes to folks who she swears are just plain crazy, from six to nine thirty, and all day on Saturday. Sunday she takes off. She says it’s God’s day, even though she spends most of it sleeping, not praying. But I’m sure God can understand that she’s had a long week. I sure do.

Mom says the only reason she has to work so hard in the first place is because our rent keeps going up. We live in Bed-Stuy, and she’s always complaining about the reason they keep raising the rent so much around this part of Brooklyn, is because white people are moving in. I don’t really get that. I mean, if I’m in a restaurant, and I order some food, and a white person walks in, all of a sudden I have to pay more for my meal? Makes no sense, but that’s what she says. I don’t really see the big deal, but that might be because no white people live on my block yet. And I can’t see none moving around here no time soon either. Shoot, black people don’t even like to move on this block. People say it’s bad, and sometimes it is, but I like to focus on the positives. We got bodegas on both ends, which is cool, and a whole bunch of what my mom calls “interesting” folks who live in the middle. To me, that just equals a good time, most of the time.

A lot of the stuff that gives my neighborhood a bad name, I don’t really mess with. The guns and drugs and all that, not really my thing. When you one of Doris’s kids, you learn early in life that school is all you need to worry about. And when it’s summertime, all you need to be concerned with then is making sure your butt got some kind of job, and staying out of trouble so that you can go back to school in September. Of course, Jazz isn’t old enough to work yet, but even she makes a few bucks every now and then, doing her little homegirls’ hair. The point is, Doris don’t play with her kids fooling around in all that street mess. Lucky for her, I don’t really have the heart to be gangster anyway. I ain’t no punk or nothing, but growing up here, I’ve seen too many dudes go down early over stupid crap like street cred, trying to prove who’s the hardest. I’m not trying to die no time soon, and I damn sure ain’t trying to go to jail. I’ve heard stories, and it definitely don’t sound like the place for me. So I always just keep cool and lay low on my block, where at least I know all the characters and how to deal with all their “interesting” nonsense.

Like my next-door neighbors, Needles and Noodles. They’re brothers, and when you talk about having a bunch of drama, these dudes might be the masters. They’re both my friends, but Noodles, the younger brother, is my ace. He’s only younger than Needles by a year, so it’s more like they’re twins, but the kind that look different. Not identical, the other kind. And really, when I think about it, Noodles actually is more like the big brother in their house, but only because Needles’s situation, which I’ll get to, makes it hard for him to do certain things sometimes.

I met them almost five years ago, when I was eleven, after the Brysons left the neighborhood. The Brysons were an old couple who lived next door, who everyone loved. Mr. Bryson had lived in that house since he was a kid, and when he met Mrs. Bryson on a Greyhound bus coming from the March on Washington, a story he used to tell me all the time, they got married and she moved in that house with him. They lived there until they were old, and out of the blue one day they were gone. Not dead. Just gone. They moved to Florida. When they got there, they sent me a postcard from their new home. On the front was a picture of Martin Luther King Jr., and on the back it said, in Mrs. Bryson’s handwriting:

Dear Allen,

We had a dream too… that one day we wouldn’t have to take the “A” train ever again. Our dream has come true.

With love,

The Brysons

I never heard from the Brysons again, and after they left, their brownstone got grimy. I don’t know who took it over, but whoever it was, they didn’t care too much about nothing when it came to who they let live there. All kinds of wild stuff started happening up in there, from crackheads to hookers. I guess the easiest way to put it is, it became a slum building—a death trap—which was crazy because it was such a nice place when the Brysons had it. Then one day Needles and Noodles showed up. Well, really just Noodles. It was a Sunday morning, and I was running to the bodega to get some bread, and when I came out the house, Noodles was sitting on my stoop. I had never seen him before, and like normal in New York, I ignored him and went on about my business. But when I got back from the store, he was still sitting there.

We made eye contact and sort of did the whole head-nod thing. Then he spoke.

“Yo,” he said. His voice was kind of raspy. I noticed he was holding a crumpled ripped-out page of a comic book, and a little pocket-size notebook that he was scribbling in.

“Yo,” I said. “You new?”

The guy looked exhausted, even though it was the middle of the day. The sun was baking, and sweat was pouring down his forehead.

I glanced down at the comic. Couldn’t recognize which one it was, which didn’t surprise me. They were never really my thing.

“Yeah,” he said, tough. He quickly folded the colorful paper up and slid it between the pages of the tiny notebook. Then he smushed it all down into his pocket.

“What floor?” I asked. I was a little confused because I didn’t think anybody had moved out.

“Second.” He tugged at the already stretched-out collar of his T-shirt.

I laughed but was still confused. I guess I just figured he was joking.

“Come on, man, I live on the second floor, so I know you don’t live there.”

“Yeah, I live on the second too,” he said with a straight face. “Over there.” He nodded his head to the house next door. The death trap.

I was stunned, but I knew better than to make it weird.

“So what you doing over here?” I asked, putting the grocery bag down on the steps.

“Sitting,” he muttered, staring at the next step down. “Would you sit on that stoop if you was me?”

Hell no, I thought. Noodles explained that he couldn’t stay all cooped up in that place, so he came outside to get some fresh air. But then he realized he also didn’t want nobody to think he lived there, so his plan was to sit on my stoop until it got dark, and then slip back into his own building. I wasn’t sure what to say. I didn’t want to start nothing because he seemed tough, and I didn’t know him yet. He looked mad, and I couldn’t help but think that wherever he came from was much better than this place. Had to be.

“I’m Ali,” I said to him, holding my hand out for dap.

He looked at it as if he was trying to figure out if he wanted to give me five or not. Then he reached out and grabbed it, our palms making that popping sound.

“Word. Roland.”

“It’s cool if you chill out here,” I said, like I owned the building or something. As if I could stop him from sitting on the concrete stairs.

The two of us sat on the stoop for a while. I wanted to ask him what comic he was reading, but judging by how fast he folded it up, that didn’t seem like a good idea. I don’t think we talked about anything in particular. I just remember acting like a tour guide, pointing out who was who and what was what on the block. I figured it was the least I could do, since he was new around here. The hard part was trying not to point to his house and say, “And that’s where all the junkies stay.”

The sun had gone almost all the way down, and the streetlights were flickering, when my mother poked her head out the window to call me up for dinner.

“Who’s that, Ali?” she asked, sort of harsh.

“This is Roland. Just moved in… next door,” I said, looking up at her, trying to drop a hint without being too obvious. Roland turned around and leaned his head back so he could see her too.

“Hi, son,” my mother said, the tone of her voice softening. I could tell that she was as surprised as I was to know that he was living in the slum building.

“Hello,” he said sadly.

Doris looked at him for a moment, sizing him up. Then she shot her eyes back toward me.

“Ali, can you bring my bread inside!”—I totally forgot!—“And come on and eat before this food gets cold,” she said in her usual gruff tone, but then turned toward Noodles, and said all nice and kind, “and you’re welcome to come eat too, sweetheart.”

As we ate, my mother asked him where he was from, but he avoided answering. Then Jazz, who at the time was only six, picked up where Doris left off and started interrogating him, asking him all kinds of crazy stuff.

“Your mom don’t cook?” she asked. My mother shot her a look, and before Noodles even had a chance to answer, Jazz changed the question.

“I mean, I mean,” she stumbled while looking at Doris out the corner of her eye, “you like SpongeBob?”

“Yeah.” The first time he smiled all day.

“Dora?” Jazz questioned.

“Yep.”

“The Young and the Restless?”

“Of course,” Noodles said, unfazed. Then he broke out laughing. He was obviously joking, but Jazz decided right then and there that she liked him.

After dinner he helped me wash dishes and thanked my mother for letting him come up and eat. Before he left, he pulled out his tiny notebook and scribbled a sketch of SpongeBob, that kinda looked like him, and kinda not, but it was still pretty good just from memory. Jazz had already left the table and was washing up for bed, so he told me to give it to her. And once it got dark enough outside, and quiet enough on the block, he made a dash into his apartment.

Though we weren’t really friends yet, he was the first person I ever had come over to hang out. I don’t really have any homeboys in the neighborhood, just because a lot of teenagers around here are messed up these days. Either they’re selling or using, and the ones that aren’t are pretending to, or have overprotective mothers like Doris who don’t want their kids hanging with nobody around here either. I have a few dudes I chill with at school, but I never really get to see them too much during the summer, just because most of them live in Harlem and I almost never go there. And they definitely don’t come to Brooklyn. So I had no choice but to keep the friends to a minimum—until Noodles.

The next morning I looked out the window, and sure enough, Noodles was sitting out there on my stoop. I remember watching him pop his head up from a different torn comic-book page, and his notepad, to watch the kids play in the hydrant. I got dressed fast and ran out to see what was up.

I guess he didn’t hear me open the door, because he flinched, big-time, when I said, “Yo, man.”

“Yo, you scared me. Don’t be creeping up on folks like that. Get you messed up, man.” He didn’t laugh, but I did. But once I realized he didn’t, I stopped. Then he laughed.

“What’s that?” I looked at the comic and the small piece of line paper covered in blue ink.

“Oh. Incredible Hulk,” he murmured while folding it up in the mini pad.

I could tell he was a little embarrassed about the comic thing—maybe he thought I would think he was some kind of geek or something. I didn’t really see what the big deal was. If you into comics, you into comics. And even though I wasn’t, I knew who Incredible Hulk was. Who didn’t?

“Aw, man, Bruce Banner a bad dude,” I said.

He opened the notepad and handed it to me.

It was one of the scenes where Bruce was upset and was turning green and becoming the Hulk. Noodles had literally redrawn the whole thing perfectly, every muscle, every hair. The only difference was he drew a Yankees hat on the Hulk, but it looked like it belonged there. The kid could really draw! Noodles said it was one of his favorites, but when I tried to give it back to him, he ripped the page out and told me I could have them both, the comic and the sketch.

He was on my stoop every single day after that, sunup to sundown. Noodles probably wouldn’t have been the friend my mom would’ve picked for me, but she felt sorry for him, plus Jazz liked him, so Mom made sure there was always extra food for him every night.

Luckily, a couple weeks later the dude who owned that building finally straightened up the outside of the apartment. A new door and some new windows. Everybody in the hood was talking about how the inside was probably still a piss pot, but at least it didn’t look as bad from the outside. At least Noodles could sit on his own stoop without feeling some kind of shame. Plus, I could sit with him, which was cool because I was getting tired of always sitting on my stoop all the time.

I bet you’re wondering how he started getting called Noodles. Well, if you ask him, he’ll say he was given that name by the hood, just because he always tries to be hard. But the truth is, it came from Jazz, who’s pretty much the master of nicknames. As a matter of fact, she’s the person who started calling me Ali. My real name is Allen, but that’s not where Ali comes from. Jazz gave me Ali after one of my boxing lessons from old man Malloy, who I’ll tell you about later. I remember leaving Malloy’s house, running down the block, busting into our apartment all gassed up, excited to show Jazz what I learned. I was bouncing around the living room, bobbing and weaving, punching the air all silly. I think Malloy had just taught me the left hook, and I hadn’t really got it down yet, so my arms were flying all over the place. Jazz laughed her head off, and made some joke about how I could be the next Muhammad Ali, as long as I keep fighting air and not real people. I won’t lie, that stung a little bit, especially since she knew I was kinda scared to have any real matches. But whatever. From then on, that’s what she called me, Ali, and then everybody else started to, too.

Noodles’s nickname story is better than mine, though. Jazz liked him a lot, especially after The Young and the Restless joke, and the SpongeBob drawing, which she had taped to her wall. Every time they saw each other after that, which was pretty much every day, they would crack jokes and tease. One day she found the perfect ammunition. She saw Noodles out the window kissing some butt-ugly girl on the stoop—Jazz’s words, not mine. She told me that the girl was twice Noodles’s size and looked like she was trying to eat his face, and she couldn’t tell if the girl was our age, or if she was an old lady, dressed like a girl our age. She said Noodles looked so scared, and that his lips were poking out and puckered so tight that it looked like he was slurping spaghetti. The next time Jazz saw him, she rode him hard about it, squeezing her lips up like a fish. At first Noodles tried to deny it. Then he said it was one of his mother’s friends, and that it was more like a family-type kiss. Whatever it was, I wasn’t about to ask no questions. I could tell he was pissed, and I was starting to figure out that he didn’t take embarrassment too well.

I was worried that he would stop being cool with me. I mean, I still didn’t know him that well for Jazz to be clowning him so bad. But I guess he had a soft spot for her, and if not her, a soft spot for dinner at my house. Either way, Jazz promised to never let it go, calling him “noodle slurper,” and stuff like that, and after a while he ended up just getting over it. And that’s how he got the name Noodles. Before that, he was just Roland James. That name is nowhere near as cool as Noodles, and even though he never gives my little sister credit, we all know he’s thankful for it now, even if it is a funny story.

Okay, so as for Needles, he’s only technically been called Needles for about a year, and his nickname story is nowhere near as funny as Noodles’s and mine, but it is way more interesting. But in order for it to make any sense, I have to start at the beginning.

I didn’t even meet Needles until about three months after I met Noodles, which I thought was weird. I mean, I knew Noodles had a brother, but I never saw him. I always wondered if he was forced to stay in the house, if he wanted to stay in the house, or if he was just someplace else, like with his father or something. All Noodles ever said about him was that he was kind of wild, which is pretty much what everybody always says about their brothers and sisters, so that wasn’t a big deal.

When I finally met him, he was with Noodles. They were walking down the block, coming from the corner store, Noodles ripping paper off cheap dime candy and tossing it on the sidewalk. I first gave Noodles some dap because I already knew him, and as soon as I reached for Needles’s hand to introduce myself, he basically started cussing me out. Scared me half to death, I swear. I couldn’t tell if this was some sort of joke, or if he just didn’t like me, but I couldn’t understand how he could not like me when we didn’t even know each other yet. But after he finished dogging me, he said, “Wassup, man” in a superquiet voice like he was scared but cool. He also apologized for coming at me that way. That really confused me. And then, to top it all off, Noodles slapped him in the back of the head. I didn’t think that was cool, but I didn’t know them well enough to be standing up for nobody.

So yeah, I thought Needles was a little bit weird, but when I told my mom about it, she made it clear, and I do mean clear, that there was nothing funny about Needles’s condition. She said the proper term for it is Tourette syndrome. So I guess it’s a syndrome and not a condition. She said that what happens is he blurts out all kinds of words whenever his brain tells him to. Not regular words like “run” or “yo” but crazy stuff like “buttface” and “fat ass.” I figured that’s what Noodles meant when he told me that Needles was “wild.”

My mother told me she had a girl on her caseload who suffered from it, and that once people learn to manage it, they can usually live normal enough lives. But judging by the way Needles acted when he spoke, and how Noodles slapped him around, I could see it being tough to, especially since it had to be pretty embarrassing.

As the months turned to years, everybody pretty much got used to Needles and Noodles, especially me. I would say we were like the three musketeers, or the three amigos, but that’s so played and has been said a million times. My mother said we were the three stooges, and Jazz said we were the three blind mice, but whatever. The point is, we were almost always together. Every holiday, they would come over for dinner. Every birthday, we’d dish out birthday punches (mine always hurt the most). And every regular day, we would just hang on the stoop. When school was in, I had to be upstairs by the time the streetlights came on, but summer, I could hang pretty late as long as I was out front. They never had a curfew, so they were always down to kick it. We would play “Would you rather,” talk trash about girls, and I would talk about sports, but neither of them knew anything about athletes, so I spent a lot of time just schooling them. Noodles would read his comics and draw in his book, and Needles, who at the time was still known as Ricky, would kick freestyle raps about whatever he saw on the street. Like, if it was a bottle on the sidewalk, he would rap about it. Or if it was a girl walking by, he would rhyme about her. And believe it or not, he was pretty good, even with the occasional outbursts that, for me, had become so normal that it was like they weren’t even happening. One rap I always remember is, “Chillin’ on the stoop, flyer than a coop, stay off the sidewalk, ’cuz there’s too much dog poop.” And then, out of nowhere, he screamed, “Shithead!”

Even when we weren’t together, we were. See—and this is gonna sound weird—but our bathrooms shared a wall, and I don’t know if it was because of water damage or what, but the wall was superthin. You could hear straight through it, and it wasn’t like we were spying on each other using the bathroom—that wouldn’t be cool—but sometimes we’d talk to each other through the wall whenever we were washing up. When it was Noodles, we wouldn’t really be saying too much, just asking if the other person was there. I don’t know why. It was just always cool knowing someone else was there, I guess. And I always knew when it was Needles, because I could hear him in there rapping and talking all kinds of crazy stuff, cussing and whatnot. Whenever he was rapping, I’d make a beat by knocking on the wall, until Doris or Jazz came banging on the bathroom door, telling me to cut it out. The point is, we were always, always, always together. That’s just the way it was.

Most of our neighborhood accepted Needles for who he was. No judgment. I mean, it’s New York. A man walking down the street dressed like Cinderella? That’s nothing. A woman with a tattoo of a pistol on her face? Who cares. So what’s the big deal about a syndrome? Whatever. It’s in our blood to get over it, especially when you’re one of our own, and by that I mean, when you live on our block.

Noodles was the only person always tripping about Needles. Despite the head swipes, Noodles was superprotective over his brother, and paranoid that people were laughing at him. He would always be shouting at somebody, or giving dirty looks to anyone he thought might be even thinking about cracking a joke about Needles. It was like he lived by some weird rule, that only he could treat Needles bad, no one else.

But nobody was ever really laughing at Needles. There was never a reason to. Needles did sweet things that were normal, just not always normal around here. He would help old ladies get their bags up the steps, ticking and accidentally cussing the whole way, calling them all kinds of names, but they didn’t care because everybody had gotten used to it. They knew he couldn’t help it, and that he was fine. Some of them would even give him a few dollars for his help.

But there were these times when Needles would sort of spaz out, but not like Noodles, who would just trip over any little thing. Needles’s was more like mini meltdowns. It was like a weird part of the syndrome where every now and then his brain would tell him to have an outburst, but it wouldn’t tell him to stop. So he would just go wild, cussing and screaming, over and over again, rapid-fire style. And even though folks around here was cool with Needles, the freak-outs were the only times people really looked at him like he was, well, crazy. I can’t lie, the first time it happened, even I was shook up watching Noodles basically drag Needles into the house, giving a middle finger to all of us looking at his shouting brother like he was some kind of animal.

About a year ago Needles had one of these fits—a bad one. It was a Sunday, and my mother was by the window and heard a bunch of commotion coming from outside. She looked out and there Needles was, sitting on the stoop next door, going off like nobody’s business! I mean, he was really going for it, calling out all kinds of “screwfaces” and “assmouths” and whatnot. By this point I’d seen him lose control tons of times, but it had never been as bad as it was that day. The worst part about it is there was a crowd of people gathered there, just listening and staring. Some were even laughing under their breath, and this time Noodles wasn’t around to shut it down.

My mother was pissed. I mean, really mad. I ran behind her as she stormed downstairs, and let me tell you, when that door flung open, those people met the worst side of Doris Brooks. She ran toward the crowd like she was getting ready to start swinging on folks, and people started walking away pretty quickly. I laughed a little bit, only because I was used to my mother being pretty scary, especially when she feels like someone is being treated wrong. After all the people left, she walked over to Needles, who was still shouting random stuff. She gave him a hug. He told her thank-you in his soft voice, and explained that he was locked out of the house. He was crying.

My mother figured that she might know something that could help him. She’s no doctor, but she is a mother and that means something. Plus, it’s pretty much her job as a case worker to know stuff about different kinds of syndromes and stuff like that. She told Needles to stay right there, and told me to wait with him while she ran back upstairs. I wasn’t so cool with that, only because he was really buggin’, but I knew I’d better do it before Doris got busy on me. Besides, he was my friend, so I stayed, even though I did wonder where Noodles was and why he left Needles out there like that.

When she came back, she had one of those black plastic bags you get from the bodega. I thought to myself, I know she ain’t bring this boy a leftover hero and some chips. And I was right. She didn’t. She brought him something even more crazy—a ball of yarn and some knitting needles. What in the world? I tried to ask what she was planning to do with those, but she shushed me before I could get it out.

“You ever seen this, Ricky?” she asked, holding up the ball of yarn with the long silver needles jammed through it.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, embarrassed.

“Do you know what to do with it?” she asked. I thought to myself, of course he doesn’t. I don’t even know what to do with it.

“Uh, not really. I saw an old lady on the train doing something with yarn and those things, but I don’t know what,” he said, shy.

Then he blurted out. I couldn’t really make out what he said. My mother didn’t even flinch. She gave me a look. The look.

“Okay, well, let me show you. I think it’ll help. Is that okay?” she asked. She wasn’t speaking to him in any sort of “slow” way. Just talking pretty regular but being sure to ask a bunch of questions. It didn’t seem like a good idea to try to force him to do anything in this particular situation.

He shook his head and worked to get out a soft “Yes.”

So my mother took the yarn, which was purple, and the two knitting needles, and started to show Needles how to knit. Knit! Like somebody’s grandma! Now, I didn’t even know my mother knew how to knit. She never knitted nothing for me and Jazz. I didn’t even know where the yarn came from. Turns out, it was something that she had learned a long time ago from her mom, and she was planning to teach Jazz how to do it, sort of as a passing-down-of-traditions type of thing, but she never had time to, with all the jobs.

“Okay, first you have to hold the needles,” she said, “like this.” She held the two needles in her hands the way my little sister used to hold her fork and knife when she was really hungry as a toddler. Like a caveman. “Got it?” she asked Needles, who had gotten real quiet—just twitching a little.

He looked at her hands for a few seconds, then positioned his hands just like hers, except he wasn’t holding any needles yet. He looked up at my mother to make sure he was doing it right.

“Like this?” he asked.

“Yep. Just like that, Ricky. Very good,” my mom said, smiling. By now my butt was hurting, so I stood up. I knew I couldn’t go home because my mother would have had a fit, so I just leaned on the shiny new door and kept watching.

“Now, this part is tricky, but you can handle it. It’s called casting on.” My mother took the ball of yarn and tied a knot on one end. She slipped it on one of the needles. Then she started looping yarn around the needle until the whole thing was covered. Seemed pretty easy to me.

Needles leaned in, closer, staring. It’s funny how some people’s eyes talk more than their mouth does. Needles is one of those people. His eyes say all kinds of stuff.

“Did you see what I did?”

“Yeah, I saw it,” he said.

“You sure?”

He smiled. “Yep.” His voice was still soft, but now it had a little happy in it. He nodded.

“Okay. Now watch closely, Ricky. I’m gonna make a stitch.” She took the needles and did something that I can’t really describe because of where I was standing. All I know is, it made a stitch.

“And here’s another one,” she said, repeating what she had just done. Now there were two stitches. I acted like I didn’t want to know nothing about knitting, but honestly, it looked kind of cool. Like, at first it was just yarn, but now it was turning into something else.

“See?” she said to Needles while making another stitch. And another one. And another one.

Needles’s eyes were following along. He nodded and moved his hands as if he were the one holding the needles. I couldn’t tell if he was getting it or not, but he kept saying he was. I wasn’t—it looked pretty tricky. Not to mention, judging from the size of those stitches, it would take Needles the rest of his life just to make a sweater.

Needles shouted out again, “Shit breath!” while slowly moving his hand toward my mom. I perked up a little just to make sure he wasn’t about to try no wild stuff, because even though I ain’t no bad dude, I know enough about throwing a punch to put him in check. I mean, he was my boy, but I had never seen him this out of control before. But my mother stayed calm. He moved his hands until they were on top of hers. Then he slowly wrapped his fingers around the needles, and my mother released her hands. Next thing I knew, Needles was holding the needles.

My mother smiled. “Go ahead, Ricky.”

He started to move his hands around, almost as if he was trying to recall the movements my mother had been making with her hands before he took the needles. Then, like it was nothing, my man Needles started knitting up a storm.

His eyes were so big, like he couldn’t even believe what he was doing, but he was doing it. You know when you have to smile but you don’t want nobody to see you smile, but it almost hurts to hold it in, so it comes out like a weird smirk? Needles did that weird smirk.

I just stood there with my mouth wide open. I couldn’t believe he figured it out, just like that.

I looked at my mother.

“What?” she said. “Oh, let me guess, you want me to show you how to knit now too?”

“Who, me? Naw, I’m good. That’s all Ricky. I ain’t trying to be looking like nobody’s granny out here,” I shot back. She knew I was just playing tough, though.

“Uh-huh. Okay, Al. You bad,” she teased. She stood up and brushed the cement dust off her butt. “Aight, I’m headed in.”

“Me too,” I said quickly. I knew that wasn’t really cool of me, but I was kind of nervous to just be sitting out there with Needles without Noodles being around. Not that day. “Later, Ricky,” I said, walking over to the next stoop, which was mine.

When me and Doris got upstairs to our apartment, Jazz was sitting in the window drinking a glass of iced tea and working on her scrapbook, which was one of her favorite things to do. She started scrapbooking when my mother found all these old pictures of her and my father and me and Jazz from back in the day. My mom decided to get an old photo album to store them all in, and put Jazz in charge of doing it. But Jazz, being Jazz, decided to do her own thing and started cutting the pictures up, taking John, my father, from one, Doris from another, and maybe her and I from a different one. Then she’d cut out a page from a magazine, maybe of a beach, or somewhere overseas like Paris, and glue the cutouts of us to the picture. Like a bootleg, imaginary, family vacation photo. It was kinda cool. When Doris first saw what she had been doing with the photos, she was pissed that Jazz was cutting up the pictures. But then as she looked more, seeing us in random places we had never been, like Africa, she laughed and thought it was pretty cute. But soon the sight of seeing us all together like that, her with my dad, page after page, turned Doris’s laughter into tears.

“Sorry,” Jazz said, staring at what she thought was something nice.

“No, baby,” my mom replied, smiling despite her wet face. “It’s fine. I love it.” It was obviously a soft spot for Doris, and after that, she never really looked at Jazz’s scrapbook again.

Jazz had been cutting and glueing, looking down on the whole thing, and was now watching Needles knit his heart out.

“What were you teaching Ricky how to knit for?” she asked as soon as we walked in. She put her glue stick down, turned the glass up to her face, and shook a piece of ice into her mouth.

My mother walked over to the sink and washed her hands while looking out the window at Needles, still going.

“Because it might help him. If he focuses on knitting, he might not have so many outbursts.”

“Yeah, he might not say stuff like, Jazz is a cornball,” I teased, looking over her shoulder at what she was working on. Us in Las Vegas.

“Ali,” my mother said warningly. Jazz looked at me, crunched on the ice in her mouth, and smiled, because she knew she had won without even saying anything back. But I really wasn’t trying to beat her.

“Jazz, it’s like when you used to have a loose tooth, ready to come out. And I always had your brother come and pinch your arm. You’d be so concerned about Al pinching your arm that you would forget all about the fact that I was pulling a tooth out your mouth. And before you knew it, it was over.”

“And I got a dollar,” Jazz bragged. “From you, the fake tooth fairy.”

I laughed and shook my head.

“The point is, Ricky will be so focused on what he’s doing with his hands, that he won’t worry about anything happening with his mouth. Understand?”

“Yep. I think I get it,” Jazz said, turning to look out the window again. “Look at him down there, knitting. I can’t even believe it.” Then it hit her. “You know what I’m gonna start calling him? Needles. Yeah, Noodles and Needles”—she paused—“I like that.”

“Okay, I got one. Would you rather live every day for the rest of your life with stinky breath, or lick the sidewalk for five minutes?” Noodles asked. He turned and looked at me with a huge grin on his face because he knew this was a tough one.

“It depends. Does gum or mints work?”

“Nope. Just shit breath, forever!” He busted out laughing.

I thought for a second. “Well, if I licked the ground, I mean, that might be the grossest thing I could ever do, but when the five minutes was up, I could just clean my mouth out.” In my head I was going back and forth between the two options. “But if I got bad breath, forever, then I might not ever be able to kiss the ladies. So, I guess I gotta go with licking the ground, man.”

Just saying it made me queasy.

“Freakin’ disgusting,” Needles said, frowning, looking out at the sidewalk. “But I would probably do the same thing.”

A sick black SUV came flying down the block. The stereo was blasting, but the music was all drowned out by the loud rattle of the bass, bumping, shaking the entire back of the truck.

“Aight, aight, I got another one,” Noodles said as the truck passed. He shook his soda can to see if anything was left in it. “Would you rather trade your little sister for a million bucks, or for a big brother, if that big brother was Jay-Z?”

“Easy. Neither,” I said, plain.

“Come on, man, you gotta pick one.”

“Nope. I wouldn’t trade her.”

Another car came cruising down the street. This time, a busted-up gray hooptie with music blasting just as loud as the fresh SUV’s.

“So you tellin’ me, you wouldn’t trade Jazz for a million bucks?”

“Nope.”

“You wouldn’t wanna be Jay-Z’s lil brother?” Noodles looked at me with a side eye like I was lying.

“Of course, but I wouldn’t trade Jazz for it!” I said, now looking at him crazy. “She’s my sister, man, and I don’t know how you and your brother roll, but for me, family is family, no matter what.”

Family is family. You can’t pick them, and you sure as hell can’t give them back. I’ve heard it a zillion times because it’s my mom’s favorite thing to say whenever she’s pissed off at me or my little sister, Jazz. It usually comes after she yells at us about something we were supposed to do but didn’t. And with my mom, yelling ain’t just yelling. She gives it everything she’s got, and I swear it feels like her words come down heavy and hard, beating on us just as bad as a leather strap. She’s never spanked us, but she always threatens to, and trust me, that’s just as bad. It happens the same every time. The shout, then the whole thing about family being family, and how you can’t pick them or give them back. Every now and then I wonder if she would give us back, if she could. Maybe trade Jazz and me in for a little dog, or an everlasting gift card for Macy’s, or something. I doubt she’d do it, but I think about that sometimes.

Me and Jazz always joke about how we didn’t get to choose either. Sometimes we say if we had a choice, we would’ve chose Oprah for a mom, but the truth is, we probably still would’ve gone with good ol’ Doris Brooks. I mean, she’s a pretty tough lady and she don’t always get it right, but there’s no doubt that she loves us. And we know we’re lucky, even when we’re getting barked at. Plus, it’s not always about us. I mean, sometimes it is, but other times it’s about other things, like our mom just being stressed out from work. She’s a social worker, and all that really means is that she takes care of mentally sick people. She makes sure they get things they need, kind of like being a step-step-stepmother to them. At least that’s the way she breaks it down to us. I could see how that could be stressful, so Jazz and I do the best we can to not add to it.

What’s crazy is that we don’t ever really see our mother that much anyway, mainly because she also has another gig at a department store in the city. So she works with the mentally ill from nine to five, and then sells clothes to folks who she swears are just plain crazy, from six to nine thirty, and all day on Saturday. Sunday she takes off. She says it’s God’s day, even though she spends most of it sleeping, not praying. But I’m sure God can understand that she’s had a long week. I sure do.

Mom says the only reason she has to work so hard in the first place is because our rent keeps going up. We live in Bed-Stuy, and she’s always complaining about the reason they keep raising the rent so much around this part of Brooklyn, is because white people are moving in. I don’t really get that. I mean, if I’m in a restaurant, and I order some food, and a white person walks in, all of a sudden I have to pay more for my meal? Makes no sense, but that’s what she says. I don’t really see the big deal, but that might be because no white people live on my block yet. And I can’t see none moving around here no time soon either. Shoot, black people don’t even like to move on this block. People say it’s bad, and sometimes it is, but I like to focus on the positives. We got bodegas on both ends, which is cool, and a whole bunch of what my mom calls “interesting” folks who live in the middle. To me, that just equals a good time, most of the time.

A lot of the stuff that gives my neighborhood a bad name, I don’t really mess with. The guns and drugs and all that, not really my thing. When you one of Doris’s kids, you learn early in life that school is all you need to worry about. And when it’s summertime, all you need to be concerned with then is making sure your butt got some kind of job, and staying out of trouble so that you can go back to school in September. Of course, Jazz isn’t old enough to work yet, but even she makes a few bucks every now and then, doing her little homegirls’ hair. The point is, Doris don’t play with her kids fooling around in all that street mess. Lucky for her, I don’t really have the heart to be gangster anyway. I ain’t no punk or nothing, but growing up here, I’ve seen too many dudes go down early over stupid crap like street cred, trying to prove who’s the hardest. I’m not trying to die no time soon, and I damn sure ain’t trying to go to jail. I’ve heard stories, and it definitely don’t sound like the place for me. So I always just keep cool and lay low on my block, where at least I know all the characters and how to deal with all their “interesting” nonsense.

Like my next-door neighbors, Needles and Noodles. They’re brothers, and when you talk about having a bunch of drama, these dudes might be the masters. They’re both my friends, but Noodles, the younger brother, is my ace. He’s only younger than Needles by a year, so it’s more like they’re twins, but the kind that look different. Not identical, the other kind. And really, when I think about it, Noodles actually is more like the big brother in their house, but only because Needles’s situation, which I’ll get to, makes it hard for him to do certain things sometimes.

I met them almost five years ago, when I was eleven, after the Brysons left the neighborhood. The Brysons were an old couple who lived next door, who everyone loved. Mr. Bryson had lived in that house since he was a kid, and when he met Mrs. Bryson on a Greyhound bus coming from the March on Washington, a story he used to tell me all the time, they got married and she moved in that house with him. They lived there until they were old, and out of the blue one day they were gone. Not dead. Just gone. They moved to Florida. When they got there, they sent me a postcard from their new home. On the front was a picture of Martin Luther King Jr., and on the back it said, in Mrs. Bryson’s handwriting:

Dear Allen,

We had a dream too… that one day we wouldn’t have to take the “A” train ever again. Our dream has come true.

With love,

The Brysons

I never heard from the Brysons again, and after they left, their brownstone got grimy. I don’t know who took it over, but whoever it was, they didn’t care too much about nothing when it came to who they let live there. All kinds of wild stuff started happening up in there, from crackheads to hookers. I guess the easiest way to put it is, it became a slum building—a death trap—which was crazy because it was such a nice place when the Brysons had it. Then one day Needles and Noodles showed up. Well, really just Noodles. It was a Sunday morning, and I was running to the bodega to get some bread, and when I came out the house, Noodles was sitting on my stoop. I had never seen him before, and like normal in New York, I ignored him and went on about my business. But when I got back from the store, he was still sitting there.

We made eye contact and sort of did the whole head-nod thing. Then he spoke.

“Yo,” he said. His voice was kind of raspy. I noticed he was holding a crumpled ripped-out page of a comic book, and a little pocket-size notebook that he was scribbling in.

“Yo,” I said. “You new?”

The guy looked exhausted, even though it was the middle of the day. The sun was baking, and sweat was pouring down his forehead.

I glanced down at the comic. Couldn’t recognize which one it was, which didn’t surprise me. They were never really my thing.

“Yeah,” he said, tough. He quickly folded the colorful paper up and slid it between the pages of the tiny notebook. Then he smushed it all down into his pocket.

“What floor?” I asked. I was a little confused because I didn’t think anybody had moved out.

“Second.” He tugged at the already stretched-out collar of his T-shirt.

I laughed but was still confused. I guess I just figured he was joking.

“Come on, man, I live on the second floor, so I know you don’t live there.”

“Yeah, I live on the second too,” he said with a straight face. “Over there.” He nodded his head to the house next door. The death trap.

I was stunned, but I knew better than to make it weird.

“So what you doing over here?” I asked, putting the grocery bag down on the steps.

“Sitting,” he muttered, staring at the next step down. “Would you sit on that stoop if you was me?”

Hell no, I thought. Noodles explained that he couldn’t stay all cooped up in that place, so he came outside to get some fresh air. But then he realized he also didn’t want nobody to think he lived there, so his plan was to sit on my stoop until it got dark, and then slip back into his own building. I wasn’t sure what to say. I didn’t want to start nothing because he seemed tough, and I didn’t know him yet. He looked mad, and I couldn’t help but think that wherever he came from was much better than this place. Had to be.

“I’m Ali,” I said to him, holding my hand out for dap.

He looked at it as if he was trying to figure out if he wanted to give me five or not. Then he reached out and grabbed it, our palms making that popping sound.

“Word. Roland.”

“It’s cool if you chill out here,” I said, like I owned the building or something. As if I could stop him from sitting on the concrete stairs.

The two of us sat on the stoop for a while. I wanted to ask him what comic he was reading, but judging by how fast he folded it up, that didn’t seem like a good idea. I don’t think we talked about anything in particular. I just remember acting like a tour guide, pointing out who was who and what was what on the block. I figured it was the least I could do, since he was new around here. The hard part was trying not to point to his house and say, “And that’s where all the junkies stay.”

The sun had gone almost all the way down, and the streetlights were flickering, when my mother poked her head out the window to call me up for dinner.

“Who’s that, Ali?” she asked, sort of harsh.

“This is Roland. Just moved in… next door,” I said, looking up at her, trying to drop a hint without being too obvious. Roland turned around and leaned his head back so he could see her too.

“Hi, son,” my mother said, the tone of her voice softening. I could tell that she was as surprised as I was to know that he was living in the slum building.

“Hello,” he said sadly.

Doris looked at him for a moment, sizing him up. Then she shot her eyes back toward me.

“Ali, can you bring my bread inside!”—I totally forgot!—“And come on and eat before this food gets cold,” she said in her usual gruff tone, but then turned toward Noodles, and said all nice and kind, “and you’re welcome to come eat too, sweetheart.”

As we ate, my mother asked him where he was from, but he avoided answering. Then Jazz, who at the time was only six, picked up where Doris left off and started interrogating him, asking him all kinds of crazy stuff.

“Your mom don’t cook?” she asked. My mother shot her a look, and before Noodles even had a chance to answer, Jazz changed the question.

“I mean, I mean,” she stumbled while looking at Doris out the corner of her eye, “you like SpongeBob?”

“Yeah.” The first time he smiled all day.

“Dora?” Jazz questioned.

“Yep.”

“The Young and the Restless?”

“Of course,” Noodles said, unfazed. Then he broke out laughing. He was obviously joking, but Jazz decided right then and there that she liked him.

After dinner he helped me wash dishes and thanked my mother for letting him come up and eat. Before he left, he pulled out his tiny notebook and scribbled a sketch of SpongeBob, that kinda looked like him, and kinda not, but it was still pretty good just from memory. Jazz had already left the table and was washing up for bed, so he told me to give it to her. And once it got dark enough outside, and quiet enough on the block, he made a dash into his apartment.

Though we weren’t really friends yet, he was the first person I ever had come over to hang out. I don’t really have any homeboys in the neighborhood, just because a lot of teenagers around here are messed up these days. Either they’re selling or using, and the ones that aren’t are pretending to, or have overprotective mothers like Doris who don’t want their kids hanging with nobody around here either. I have a few dudes I chill with at school, but I never really get to see them too much during the summer, just because most of them live in Harlem and I almost never go there. And they definitely don’t come to Brooklyn. So I had no choice but to keep the friends to a minimum—until Noodles.

The next morning I looked out the window, and sure enough, Noodles was sitting out there on my stoop. I remember watching him pop his head up from a different torn comic-book page, and his notepad, to watch the kids play in the hydrant. I got dressed fast and ran out to see what was up.

I guess he didn’t hear me open the door, because he flinched, big-time, when I said, “Yo, man.”

“Yo, you scared me. Don’t be creeping up on folks like that. Get you messed up, man.” He didn’t laugh, but I did. But once I realized he didn’t, I stopped. Then he laughed.

“What’s that?” I looked at the comic and the small piece of line paper covered in blue ink.

“Oh. Incredible Hulk,” he murmured while folding it up in the mini pad.

I could tell he was a little embarrassed about the comic thing—maybe he thought I would think he was some kind of geek or something. I didn’t really see what the big deal was. If you into comics, you into comics. And even though I wasn’t, I knew who Incredible Hulk was. Who didn’t?

“Aw, man, Bruce Banner a bad dude,” I said.

He opened the notepad and handed it to me.

It was one of the scenes where Bruce was upset and was turning green and becoming the Hulk. Noodles had literally redrawn the whole thing perfectly, every muscle, every hair. The only difference was he drew a Yankees hat on the Hulk, but it looked like it belonged there. The kid could really draw! Noodles said it was one of his favorites, but when I tried to give it back to him, he ripped the page out and told me I could have them both, the comic and the sketch.

He was on my stoop every single day after that, sunup to sundown. Noodles probably wouldn’t have been the friend my mom would’ve picked for me, but she felt sorry for him, plus Jazz liked him, so Mom made sure there was always extra food for him every night.

Luckily, a couple weeks later the dude who owned that building finally straightened up the outside of the apartment. A new door and some new windows. Everybody in the hood was talking about how the inside was probably still a piss pot, but at least it didn’t look as bad from the outside. At least Noodles could sit on his own stoop without feeling some kind of shame. Plus, I could sit with him, which was cool because I was getting tired of always sitting on my stoop all the time.

I bet you’re wondering how he started getting called Noodles. Well, if you ask him, he’ll say he was given that name by the hood, just because he always tries to be hard. But the truth is, it came from Jazz, who’s pretty much the master of nicknames. As a matter of fact, she’s the person who started calling me Ali. My real name is Allen, but that’s not where Ali comes from. Jazz gave me Ali after one of my boxing lessons from old man Malloy, who I’ll tell you about later. I remember leaving Malloy’s house, running down the block, busting into our apartment all gassed up, excited to show Jazz what I learned. I was bouncing around the living room, bobbing and weaving, punching the air all silly. I think Malloy had just taught me the left hook, and I hadn’t really got it down yet, so my arms were flying all over the place. Jazz laughed her head off, and made some joke about how I could be the next Muhammad Ali, as long as I keep fighting air and not real people. I won’t lie, that stung a little bit, especially since she knew I was kinda scared to have any real matches. But whatever. From then on, that’s what she called me, Ali, and then everybody else started to, too.

Noodles’s nickname story is better than mine, though. Jazz liked him a lot, especially after The Young and the Restless joke, and the SpongeBob drawing, which she had taped to her wall. Every time they saw each other after that, which was pretty much every day, they would crack jokes and tease. One day she found the perfect ammunition. She saw Noodles out the window kissing some butt-ugly girl on the stoop—Jazz’s words, not mine. She told me that the girl was twice Noodles’s size and looked like she was trying to eat his face, and she couldn’t tell if the girl was our age, or if she was an old lady, dressed like a girl our age. She said Noodles looked so scared, and that his lips were poking out and puckered so tight that it looked like he was slurping spaghetti. The next time Jazz saw him, she rode him hard about it, squeezing her lips up like a fish. At first Noodles tried to deny it. Then he said it was one of his mother’s friends, and that it was more like a family-type kiss. Whatever it was, I wasn’t about to ask no questions. I could tell he was pissed, and I was starting to figure out that he didn’t take embarrassment too well.

I was worried that he would stop being cool with me. I mean, I still didn’t know him that well for Jazz to be clowning him so bad. But I guess he had a soft spot for her, and if not her, a soft spot for dinner at my house. Either way, Jazz promised to never let it go, calling him “noodle slurper,” and stuff like that, and after a while he ended up just getting over it. And that’s how he got the name Noodles. Before that, he was just Roland James. That name is nowhere near as cool as Noodles, and even though he never gives my little sister credit, we all know he’s thankful for it now, even if it is a funny story.

Okay, so as for Needles, he’s only technically been called Needles for about a year, and his nickname story is nowhere near as funny as Noodles’s and mine, but it is way more interesting. But in order for it to make any sense, I have to start at the beginning.

I didn’t even meet Needles until about three months after I met Noodles, which I thought was weird. I mean, I knew Noodles had a brother, but I never saw him. I always wondered if he was forced to stay in the house, if he wanted to stay in the house, or if he was just someplace else, like with his father or something. All Noodles ever said about him was that he was kind of wild, which is pretty much what everybody always says about their brothers and sisters, so that wasn’t a big deal.

When I finally met him, he was with Noodles. They were walking down the block, coming from the corner store, Noodles ripping paper off cheap dime candy and tossing it on the sidewalk. I first gave Noodles some dap because I already knew him, and as soon as I reached for Needles’s hand to introduce myself, he basically started cussing me out. Scared me half to death, I swear. I couldn’t tell if this was some sort of joke, or if he just didn’t like me, but I couldn’t understand how he could not like me when we didn’t even know each other yet. But after he finished dogging me, he said, “Wassup, man” in a superquiet voice like he was scared but cool. He also apologized for coming at me that way. That really confused me. And then, to top it all off, Noodles slapped him in the back of the head. I didn’t think that was cool, but I didn’t know them well enough to be standing up for nobody.

So yeah, I thought Needles was a little bit weird, but when I told my mom about it, she made it clear, and I do mean clear, that there was nothing funny about Needles’s condition. She said the proper term for it is Tourette syndrome. So I guess it’s a syndrome and not a condition. She said that what happens is he blurts out all kinds of words whenever his brain tells him to. Not regular words like “run” or “yo” but crazy stuff like “buttface” and “fat ass.” I figured that’s what Noodles meant when he told me that Needles was “wild.”

My mother told me she had a girl on her caseload who suffered from it, and that once people learn to manage it, they can usually live normal enough lives. But judging by the way Needles acted when he spoke, and how Noodles slapped him around, I could see it being tough to, especially since it had to be pretty embarrassing.

As the months turned to years, everybody pretty much got used to Needles and Noodles, especially me. I would say we were like the three musketeers, or the three amigos, but that’s so played and has been said a million times. My mother said we were the three stooges, and Jazz said we were the three blind mice, but whatever. The point is, we were almost always together. Every holiday, they would come over for dinner. Every birthday, we’d dish out birthday punches (mine always hurt the most). And every regular day, we would just hang on the stoop. When school was in, I had to be upstairs by the time the streetlights came on, but summer, I could hang pretty late as long as I was out front. They never had a curfew, so they were always down to kick it. We would play “Would you rather,” talk trash about girls, and I would talk about sports, but neither of them knew anything about athletes, so I spent a lot of time just schooling them. Noodles would read his comics and draw in his book, and Needles, who at the time was still known as Ricky, would kick freestyle raps about whatever he saw on the street. Like, if it was a bottle on the sidewalk, he would rap about it. Or if it was a girl walking by, he would rhyme about her. And believe it or not, he was pretty good, even with the occasional outbursts that, for me, had become so normal that it was like they weren’t even happening. One rap I always remember is, “Chillin’ on the stoop, flyer than a coop, stay off the sidewalk, ’cuz there’s too much dog poop.” And then, out of nowhere, he screamed, “Shithead!”

Even when we weren’t together, we were. See—and this is gonna sound weird—but our bathrooms shared a wall, and I don’t know if it was because of water damage or what, but the wall was superthin. You could hear straight through it, and it wasn’t like we were spying on each other using the bathroom—that wouldn’t be cool—but sometimes we’d talk to each other through the wall whenever we were washing up. When it was Noodles, we wouldn’t really be saying too much, just asking if the other person was there. I don’t know why. It was just always cool knowing someone else was there, I guess. And I always knew when it was Needles, because I could hear him in there rapping and talking all kinds of crazy stuff, cussing and whatnot. Whenever he was rapping, I’d make a beat by knocking on the wall, until Doris or Jazz came banging on the bathroom door, telling me to cut it out. The point is, we were always, always, always together. That’s just the way it was.

Most of our neighborhood accepted Needles for who he was. No judgment. I mean, it’s New York. A man walking down the street dressed like Cinderella? That’s nothing. A woman with a tattoo of a pistol on her face? Who cares. So what’s the big deal about a syndrome? Whatever. It’s in our blood to get over it, especially when you’re one of our own, and by that I mean, when you live on our block.

Noodles was the only person always tripping about Needles. Despite the head swipes, Noodles was superprotective over his brother, and paranoid that people were laughing at him. He would always be shouting at somebody, or giving dirty looks to anyone he thought might be even thinking about cracking a joke about Needles. It was like he lived by some weird rule, that only he could treat Needles bad, no one else.

But nobody was ever really laughing at Needles. There was never a reason to. Needles did sweet things that were normal, just not always normal around here. He would help old ladies get their bags up the steps, ticking and accidentally cussing the whole way, calling them all kinds of names, but they didn’t care because everybody had gotten used to it. They knew he couldn’t help it, and that he was fine. Some of them would even give him a few dollars for his help.

But there were these times when Needles would sort of spaz out, but not like Noodles, who would just trip over any little thing. Needles’s was more like mini meltdowns. It was like a weird part of the syndrome where every now and then his brain would tell him to have an outburst, but it wouldn’t tell him to stop. So he would just go wild, cussing and screaming, over and over again, rapid-fire style. And even though folks around here was cool with Needles, the freak-outs were the only times people really looked at him like he was, well, crazy. I can’t lie, the first time it happened, even I was shook up watching Noodles basically drag Needles into the house, giving a middle finger to all of us looking at his shouting brother like he was some kind of animal.

About a year ago Needles had one of these fits—a bad one. It was a Sunday, and my mother was by the window and heard a bunch of commotion coming from outside. She looked out and there Needles was, sitting on the stoop next door, going off like nobody’s business! I mean, he was really going for it, calling out all kinds of “screwfaces” and “assmouths” and whatnot. By this point I’d seen him lose control tons of times, but it had never been as bad as it was that day. The worst part about it is there was a crowd of people gathered there, just listening and staring. Some were even laughing under their breath, and this time Noodles wasn’t around to shut it down.

My mother was pissed. I mean, really mad. I ran behind her as she stormed downstairs, and let me tell you, when that door flung open, those people met the worst side of Doris Brooks. She ran toward the crowd like she was getting ready to start swinging on folks, and people started walking away pretty quickly. I laughed a little bit, only because I was used to my mother being pretty scary, especially when she feels like someone is being treated wrong. After all the people left, she walked over to Needles, who was still shouting random stuff. She gave him a hug. He told her thank-you in his soft voice, and explained that he was locked out of the house. He was crying.

My mother figured that she might know something that could help him. She’s no doctor, but she is a mother and that means something. Plus, it’s pretty much her job as a case worker to know stuff about different kinds of syndromes and stuff like that. She told Needles to stay right there, and told me to wait with him while she ran back upstairs. I wasn’t so cool with that, only because he was really buggin’, but I knew I’d better do it before Doris got busy on me. Besides, he was my friend, so I stayed, even though I did wonder where Noodles was and why he left Needles out there like that.

When she came back, she had one of those black plastic bags you get from the bodega. I thought to myself, I know she ain’t bring this boy a leftover hero and some chips. And I was right. She didn’t. She brought him something even more crazy—a ball of yarn and some knitting needles. What in the world? I tried to ask what she was planning to do with those, but she shushed me before I could get it out.

“You ever seen this, Ricky?” she asked, holding up the ball of yarn with the long silver needles jammed through it.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, embarrassed.

“Do you know what to do with it?” she asked. I thought to myself, of course he doesn’t. I don’t even know what to do with it.

“Uh, not really. I saw an old lady on the train doing something with yarn and those things, but I don’t know what,” he said, shy.

Then he blurted out. I couldn’t really make out what he said. My mother didn’t even flinch. She gave me a look. The look.

“Okay, well, let me show you. I think it’ll help. Is that okay?” she asked. She wasn’t speaking to him in any sort of “slow” way. Just talking pretty regular but being sure to ask a bunch of questions. It didn’t seem like a good idea to try to force him to do anything in this particular situation.

He shook his head and worked to get out a soft “Yes.”

So my mother took the yarn, which was purple, and the two knitting needles, and started to show Needles how to knit. Knit! Like somebody’s grandma! Now, I didn’t even know my mother knew how to knit. She never knitted nothing for me and Jazz. I didn’t even know where the yarn came from. Turns out, it was something that she had learned a long time ago from her mom, and she was planning to teach Jazz how to do it, sort of as a passing-down-of-traditions type of thing, but she never had time to, with all the jobs.

“Okay, first you have to hold the needles,” she said, “like this.” She held the two needles in her hands the way my little sister used to hold her fork and knife when she was really hungry as a toddler. Like a caveman. “Got it?” she asked Needles, who had gotten real quiet—just twitching a little.

He looked at her hands for a few seconds, then positioned his hands just like hers, except he wasn’t holding any needles yet. He looked up at my mother to make sure he was doing it right.

“Like this?” he asked.

“Yep. Just like that, Ricky. Very good,” my mom said, smiling. By now my butt was hurting, so I stood up. I knew I couldn’t go home because my mother would have had a fit, so I just leaned on the shiny new door and kept watching.

“Now, this part is tricky, but you can handle it. It’s called casting on.” My mother took the ball of yarn and tied a knot on one end. She slipped it on one of the needles. Then she started looping yarn around the needle until the whole thing was covered. Seemed pretty easy to me.

Needles leaned in, closer, staring. It’s funny how some people’s eyes talk more than their mouth does. Needles is one of those people. His eyes say all kinds of stuff.

“Did you see what I did?”

“Yeah, I saw it,” he said.

“You sure?”

He smiled. “Yep.” His voice was still soft, but now it had a little happy in it. He nodded.

“Okay. Now watch closely, Ricky. I’m gonna make a stitch.” She took the needles and did something that I can’t really describe because of where I was standing. All I know is, it made a stitch.

“And here’s another one,” she said, repeating what she had just done. Now there were two stitches. I acted like I didn’t want to know nothing about knitting, but honestly, it looked kind of cool. Like, at first it was just yarn, but now it was turning into something else.

“See?” she said to Needles while making another stitch. And another one. And another one.

Needles’s eyes were following along. He nodded and moved his hands as if he were the one holding the needles. I couldn’t tell if he was getting it or not, but he kept saying he was. I wasn’t—it looked pretty tricky. Not to mention, judging from the size of those stitches, it would take Needles the rest of his life just to make a sweater.

Needles shouted out again, “Shit breath!” while slowly moving his hand toward my mom. I perked up a little just to make sure he wasn’t about to try no wild stuff, because even though I ain’t no bad dude, I know enough about throwing a punch to put him in check. I mean, he was my boy, but I had never seen him this out of control before. But my mother stayed calm. He moved his hands until they were on top of hers. Then he slowly wrapped his fingers around the needles, and my mother released her hands. Next thing I knew, Needles was holding the needles.

My mother smiled. “Go ahead, Ricky.”

He started to move his hands around, almost as if he was trying to recall the movements my mother had been making with her hands before he took the needles. Then, like it was nothing, my man Needles started knitting up a storm.

His eyes were so big, like he couldn’t even believe what he was doing, but he was doing it. You know when you have to smile but you don’t want nobody to see you smile, but it almost hurts to hold it in, so it comes out like a weird smirk? Needles did that weird smirk.

I just stood there with my mouth wide open. I couldn’t believe he figured it out, just like that.

I looked at my mother.

“What?” she said. “Oh, let me guess, you want me to show you how to knit now too?”

“Who, me? Naw, I’m good. That’s all Ricky. I ain’t trying to be looking like nobody’s granny out here,” I shot back. She knew I was just playing tough, though.

“Uh-huh. Okay, Al. You bad,” she teased. She stood up and brushed the cement dust off her butt. “Aight, I’m headed in.”

“Me too,” I said quickly. I knew that wasn’t really cool of me, but I was kind of nervous to just be sitting out there with Needles without Noodles being around. Not that day. “Later, Ricky,” I said, walking over to the next stoop, which was mine.

When me and Doris got upstairs to our apartment, Jazz was sitting in the window drinking a glass of iced tea and working on her scrapbook, which was one of her favorite things to do. She started scrapbooking when my mother found all these old pictures of her and my father and me and Jazz from back in the day. My mom decided to get an old photo album to store them all in, and put Jazz in charge of doing it. But Jazz, being Jazz, decided to do her own thing and started cutting the pictures up, taking John, my father, from one, Doris from another, and maybe her and I from a different one. Then she’d cut out a page from a magazine, maybe of a beach, or somewhere overseas like Paris, and glue the cutouts of us to the picture. Like a bootleg, imaginary, family vacation photo. It was kinda cool. When Doris first saw what she had been doing with the photos, she was pissed that Jazz was cutting up the pictures. But then as she looked more, seeing us in random places we had never been, like Africa, she laughed and thought it was pretty cute. But soon the sight of seeing us all together like that, her with my dad, page after page, turned Doris’s laughter into tears.

“Sorry,” Jazz said, staring at what she thought was something nice.

“No, baby,” my mom replied, smiling despite her wet face. “It’s fine. I love it.” It was obviously a soft spot for Doris, and after that, she never really looked at Jazz’s scrapbook again.

Jazz had been cutting and glueing, looking down on the whole thing, and was now watching Needles knit his heart out.

“What were you teaching Ricky how to knit for?” she asked as soon as we walked in. She put her glue stick down, turned the glass up to her face, and shook a piece of ice into her mouth.

My mother walked over to the sink and washed her hands while looking out the window at Needles, still going.

“Because it might help him. If he focuses on knitting, he might not have so many outbursts.”

“Yeah, he might not say stuff like, Jazz is a cornball,” I teased, looking over her shoulder at what she was working on. Us in Las Vegas.

“Ali,” my mother said warningly. Jazz looked at me, crunched on the ice in her mouth, and smiled, because she knew she had won without even saying anything back. But I really wasn’t trying to beat her.

“Jazz, it’s like when you used to have a loose tooth, ready to come out. And I always had your brother come and pinch your arm. You’d be so concerned about Al pinching your arm that you would forget all about the fact that I was pulling a tooth out your mouth. And before you knew it, it was over.”

“And I got a dollar,” Jazz bragged. “From you, the fake tooth fairy.”

I laughed and shook my head.

“The point is, Ricky will be so focused on what he’s doing with his hands, that he won’t worry about anything happening with his mouth. Understand?”

“Yep. I think I get it,” Jazz said, turning to look out the window again. “Look at him down there, knitting. I can’t even believe it.” Then it hit her. “You know what I’m gonna start calling him? Needles. Yeah, Noodles and Needles”—she paused—“I like that.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (January 7, 2014)

- Length: 240 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442459472

- Grades: 7 and up

- Ages: 12 - 99

- Lexile ® 740L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- CCBC Choices (Cooperative Children's Book Council)

- ALA Best Books For Young Adults

- Georgia Peach Book Award for Teen Readers Nominee

- Kansas NEA Reading Circle List High School Title

- NYPL Best Books for Teens

- Capital Choices Noteworthy Books for Children's and Teens (DC)

- TAYSHAS Reading List (TX)

- ALA Coretta Scott King John Steptoe New Talent Award

- CBC Children's Choice Book Award Finalist

- ALA Margaret A. Edwards Award

- Cybils Award Finalist

- Eliot Rosewater Indiana High School Book Award Nominee

- Louisiana Teen Readers' Choice Award Nominee

- In the Margins Top Ten List

- James Cook Book Award Honor (OH)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): When I Was the Greatest Hardcover 9781442459472

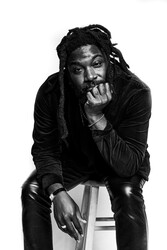

- Author Photo (jpg): Jason Reynolds Photograph (c) Adedayo "Dayo" Kosoko(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit