Get our latest staff recommendations, award news and digital catalog links right to your inbox.

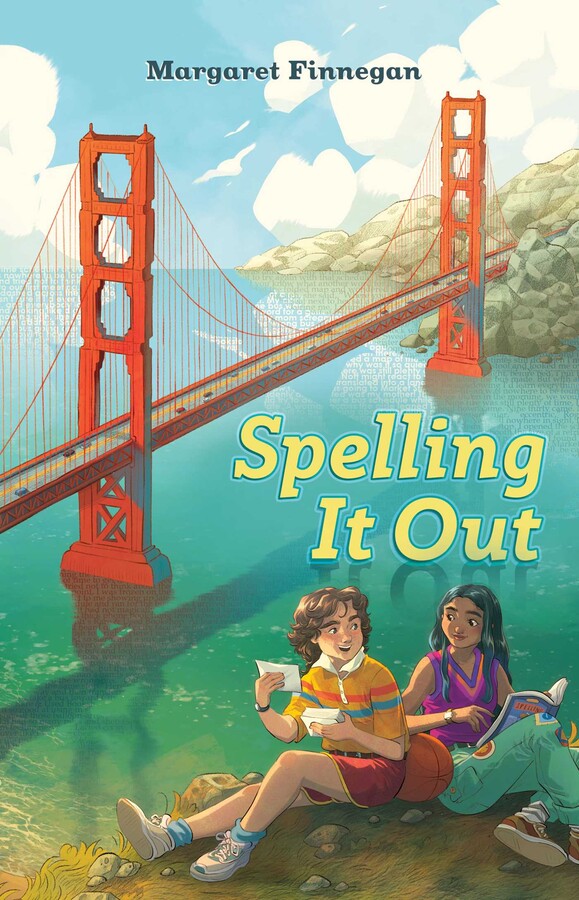

Spelling It Out

Table of Contents

About The Book

Ben Bellini didn’t mean to become a champion speller—after all, he’s not a nerd—but he sure does like spelling bee glory now that it’s found him. He might even be good enough for the Scripps National Spelling Bee in Washington, DC! And what better way to prepare than to train with a professional spelling coach in San Francisco, where his nan lives?

Through his adventures, Ben gets to know the city—and competitor Asha Krishnakumar, who’s equally determined to spell her way to victory. But Ben also starts having odd interactions with his nan that leave him feeling like he’s missing something. Where is Nan’s forgetfulness coming from? And will anyone even believe him if he tries to get help?

Between showing up for his loved ones and pursuing his own dreams, Ben will need to spend this summer figuring out what he owes others…and what he owes himself.

Excerpt

Clodpoll: noun. A foolish person.

Picture it: 1985. There I am: Ben Bellini. Sixth grade, but probably looking closer to fifth. (Why? Because my parents threw me into kindergarten when I was four and a half years old, and I was a shrimp to boot.) I’m standing on a middle school stage somewhere in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley. My dark, shaggy hair tickles my neck. A collared shirt and black pants hang off my puny frame. There’s a microphone in front of me—and behind me, about sixty of those uncomfortable folding chairs found in school auditoriums. When this day began, there was a kid seated in each one. Now most of those chairs are empty.

A voice from the audience says, “The word is clodpoll.”

I lean forward, my mouth almost touching the microphone. The auditorium lights have been making me squint all day, but I can still see the pronouncer, and the way she bites her lower lip every time a speller pauses a beat too long. Like I’ve just done.

I swallow. “Can you use it in a sentence?”

The pronouncer looks down at her card. She reads, “The clodpoll wore shorts in a snowstorm.”

My heart is beating faster now. I catch my mother’s eye. She’s sitting toward the middle of the auditorium with my father. She’s smiling, nodding. Waiting.

Behind me, I can hear the fidgety rustles of the remaining spellers. They can already sense what’s going to happen. I can sense it too, and my stomach twists with dread.

I take a deep breath. “Clodpoll. C-L-A-U-D-E-P-O-L-E.”

The pronouncer’s shoulders slump. A bell rings. And I walk off the stage to take my place with the other losers of the Southern California Regional Spelling Bee.

Even now, all these years later, I remember it perfectly. It’s like that memory has its own room in my brain.

The minute I was off the stage, I was desperate to go home and lick my wounds in peace. But when I gave my parents a pleading look, their faces stiffened, and their eyes told me that I was going to toughen up and be a good sport even if it killed me.

So that’s what I did. I sat there, lips pulled tight, no emotions showing, as speller after speller went down. They were felled by words like phenomenon, bursitis, and accommodate, and when they walked off the stage with heavy feet, they collapsed into the chairs around me.

Finally, only two spellers remained: a curly-haired boy in a three-piece suit and a girl with a heart-shaped mouth, who swayed back and forth every time she said a letter.

“The word,” said the pronouncer, “is liaison.”

The boy was up first. He said, “May I have a definition?”

“Noun. A person tasked with establishing and maintaining communication and cooperation between groups of people.”

“Can you use it in a sentence?” he asked.

“The air force liaison made sure that the army and navy generals had the proper information.”

“Language of origin?” That was not a question I had ever asked, but my competitors had been asking it all day long. I couldn’t figure out why. How could it help with anything if you didn’t know the other language?

“French.”

The boy licked his lips. He scrunched up his nose as if the word had a bad smell to it, pausing just long enough for us to know that he didn’t have a clue.

His cleared his voice and said, “Liaison. L-A-I-S-O-N.”

Down fell the pronouncer’s shoulders. Her voice pained, she said, “That is incorrect.” She turned to the girl, told her it was her turn. “The word is milieu.”

The girl took a deep breath.

(We all took a deep breath.)

She swallowed. Then, her voice clear and strong, she answered, “Milieu. M-I-L-I-E-U.”

We knew. We knew from the smile on the girl’s face and the straight line of the pronouncer’s shoulders: she’d beaten us all. She’d just won the regional bee and advanced to the queen bee of all bees: the Scripps National Spelling Bee in Washington, DC.

Eleven people finished ahead of me that day. My parents made me shake hands and congratulate every one of them, but that girl? The girl who won? Congratulating her was the hardest of all. She seemed so truly, one hundred percent authentically happy that it was like staring at the sun.

I couldn’t do it. I could only blink and look away.

On the drive home, I didn’t say a word.

“You should be proud of yourself,” said Mom, in her cajoling way. “You did great. Twelfth place is amazing! Who cares if you didn’t win? Winning doesn’t matter. You did your best. That’s what counts.” From her place in the front passenger seat, she gave Dad’s arm a whack. “Tell Ben how proud we are of him.”

“Of course we’re proud of you,” said Dad, his head moving left and right as he looked for signs to the freeway. Then he shrugged. “And besides, it’s not like winning was a big dream of yours. Right?”

I slumped lower in my seat. He was kind of right; I hadn’t gone looking for spelling glory. I’d won my class bee without even knowing there was going to be a class bee. But as I went on to win my school bee, and then my district bee, I was shocked to discover that I loved competitive spelling. I loved the anticipation of waiting for my turn. I loved the jolt of energy that struck me when I stood in front of the microphone, staring down the pronouncer. Most of all, I loved the trance of pure focus that came over me as I visualized each word in all its possibilities. It was so different from the flustered, tongue-tied feeling I usually got when time was short, the stakes were high, and I was trying to find just the right thing to say.

And, let’s be honest—winning feels good.

Maybe that’s why losing that regional bee sliced right through my heart. I know that sounds dramatic, but I really thought I’d win. The other bees had been so easy, so effortless! It had never occurred to me that they wouldn’t stay that way.

“Come on, Ben,” coaxed my mom. “Say something—anything.”

But I couldn’t. I would have cried—and listen, my mom always insisted that it was okay to cry, but she didn’t go to my middle school. She did not understand that crying—especially a boy crying—was like blowing a dog whistle in a world full of wolves.

Actually, I did say something in the car—I remember now. Quietly, just loud enough to be heard, I asked if we could get hamburgers. I said it really pitifully, too, trying to weasel one good thing out of a rotten day. But not even my sad attempt was enough to milk fried and salty sympathy out of my parents.

“Oh, you know fast food is bad for you,” said Mom, throwing me a homemade granola bar (that she had probably sweetened with pureed prunes).

“You think money grows on trees?” said my dad. “You know better than that.”

“I’ll tell you what,” said Mom. “I’ll make those cheesy potato skins you like for dinner. They’re not super healthy, but you’ve earned it. How’s that sound?”

It did not sound as good as advancing to the National Spelling Bee. (Or consolation hamburgers.) But those potato skins were deliciously cheesy, so I grunted approval anyway.

When we got home, all I wanted to do was pancake flat on my bed and bury my face in my pillow. But before I reached my room, my sister poked her head out of her door. I wasn’t looking at her, but I could feel her frown, and I remembered the day I’d won that first bee at our school. “You think you’re so great,” she’d said. “It’s just spelling, Ben. Nobody cares.”

Mom usually avoided our sibling drama, but after my loss she wasn’t taking any chances. Before Erin could even open her mouth, she said, “Give your brother space.” Then, giving my shoulder a consoling pat, she added, “The day didn’t go the way he’d hoped.”

And here’s how Erin replied: “What did he expect? He never even studied.”

That was it. No “Too bad.” No “What a shame.” Just “What did he expect? He never even studied.”

Always five seconds from the clever—or even sensible—thing to say, I sputtered like a baby. “Only a nerd would study for a spelling bee.”

Snorting, Erin said, “How many times do I have to tell you? You are a nerd.” Which may not sound bad—but trust me, it sure wasn’t a compliment in 1985.

With a voice rumbling like distant thunder, Mom said, “Erin…”

“What?” Erin asked, pretend-innocent. “Am I wrong? The more you practice at something, the better you get. That’s what my softball coach says. Did you ever see Ben practice? I never saw him practice.”

“Yeah… well…” I stomped into the room I shared with my nine-year-old brother. “Nobody practices for spelling bees.”

Mark was sitting on the carpet. He was playing with a couple of Star Wars action figures. They’d once been mine, but Erin had told me months earlier that middle school boys who played with dolls, even tiny plastic manly ones, got themselves stuffed in lockers. For sure.

When I closed the door behind me, Mark said, “So I guess you didn’t win.” No matter whether he was happy or sad, Mark always had a sort of Eeyore voice. It should have added a nice texture to my pity party, but impossibly, it did the opposite.

I dropped onto my bed not a sad pancake, but a half-risen soufflé, leavened by a sudden sense of acceptance. I hadn’t won. It was as simple as that, and feeling sorry for myself wouldn’t change anything. If I could accept that, I could accept something else: that, as annoying as it was, Erin was right. I should have studied. It wasn’t true that nobody studied for spelling bees; other kids did. At the regional bee, kids pulled out dictionaries and flipped through flash cards during every break and between every round. The girl who’d won? I’d overheard her saying that she was taking French lessons so she could master French words.

I’d watched every competitor silently, in wonder. The fact was, I had never studied for anything, ever. Not a weekly spelling test. Not a math quiz. Even when seeing the kids who had studied for the regional bee, it never occurred to me that I might have done the same. I would not have known where to begin if it had.

When Scott Rothenberg and I walked to school the next day, I never mentioned the regional bee. Actually, I hadn’t even told him it was happening—and he’d been my best friend since he moved next door when we were both four years old! I hadn’t mentioned the regional bee to anyone outside my family. At my school, you kept your academic enthusiasm to yourself. If you didn’t want to be swatted like a gnat, you knew better than to answer too many questions in class, or act eager about school projects, or recount the weekend you spent at a spelling bee.

My friends weren’t jerks, though. They’d actually been excited when I defeated Dawn Reece in my first spelling bee, the class bee I hadn’t known about. (Any middle school boy who beat any middle school girl at anything was somehow heroic.) But soon enough, the whole thing stumped them.

“You’re just sitting there spelling. How is that fun? Why don’t you lose on purpose so you can be done already?” Jeremy Chu asked me before the district bee. He and a few of my other friends had just discovered heavy metal. The topic had driven a bit of wedge between us—not because my friends cared that the music was a drill to my ears, but because I couldn’t keep up with their constant conversations about Metallica and Twisted Sister. With Jeremy’s suggestion that I lose a bee on purpose, I felt the wedge drive in further.

To my relief, Scott answered, “Hey, Ben’s smart to keep winning,” and I thought, Phew, I’ll always have my best friend Scott. Then he added, “Spelling bees are a great way to meet girls. Haven’t you noticed how many girls compete in those things?” And, since I actually liked spelling and had never given the number of girls in the bee any thought, I thought, Oh. I wonder if I will always have my best friend Scott?

But on the day after the regional bee, I wasn’t thinking about that. I was only thinking about how lonely it feels when you lose a regional spelling bee and no one knows. But lo and behold, my homeroom teacher knew. She shone a wide smile at me. Then she happily declared to the class, “I want you all to know that Ben Bellini came in twelfth at the Southern California Regional Spelling Bee this weekend. Ben, we are all very proud of you.”

Except for Scott patting my arm and saying “Good job,” no one batted an eye. Which only goes to show that, surprisingly, sometimes losing a regional spelling bee and people knowing about it feels even lonelier than when it’s a secret.

The stony faces of my peers did not stop my teacher, who just kept talking. “What was your final word?” she asked me.

“Clodpoll,” I answered.

Screwing up her face, she asked, “What’s a clodpoll?”

I said, “A person who’d wear shorts in a snowstorm.”

A few kids snickered, and from the back of the room a voice said, “Ha, ha. Clodpoll.”

“Well,” said my teacher. “I certainly hope you’ll try again next year. You can compete all the way through age thirteen, you know. Not everyone is such a gifted speller.”

More kids snickered. Then the same voice from the back of the room said sarcastically, “Not everyone is such a gifted speller.”

An electric pulse seemed to charge the air, and then the whole class busted into guffaws and snorts of laughter. Even I laughed—because if you’re not in on the joke, you are the joke.

“Not everyone is such a gifted speller,” my teacher insisted, her voice squeaky, as if this were the point of no return, the point when her authority would be either confirmed or destroyed.

“One day, you’ll see. It’s very cool what Ben did!”

We went right on laughing. Because honestly, of all the gifts a kid could possess, who would choose spelling? Especially if this was the reaction it provoked?

I shook my head. I was done with competitive spelling. I would not be that kid: the nerd, the doofus, the dweeb, the gifted—but not gifted enough—speller. I would be fine, instead, being a clodpoll.

Why We Love It

“If you’ve never been to San Francisco in the summer, get ready to be transported there by this funny, heartfelt story! From the bay to the public library to the crowded buses (where you’ll need to keep your city face on), Ben Bellini’s world is so real that you’ll feel like you’re right there with him. But the real magic here is Ben himself: smart, clever, and determined to find spelling bee glory (without revealing himself as a nerd), you’ll be rooting for him from start to finish.”

—Feather F., Editor, on Spelling It Out

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (May 13, 2025)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781665930116

- Grades: 3 - 7

- Ages: 8 - 12

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Finnegan touches on . . . gender roles, prejudice, and masculinity across an introspective tale about finding and staying true to oneself.”

– Publishers Weekly

"A sympathetic character, Ben struggles to prove himself to those around him, while becoming increasingly aware that they have troubles too. . . . Timeless in its portrayal of a middle-school boy trying to find his way.”

– Booklist

“In his well-drawn character arc, Ben shoulders responsibilities beyond his years to help Nan: His growth signals the champion he’s becoming in his personal life. A thoughtful coming-of-age story.”

– Kirkus Reviews

Resources and Downloads

Activity Sheets

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Spelling It Out Hardcover 9781665930116